Kenya’s Maasai Mara is full of surprises, 36 years on

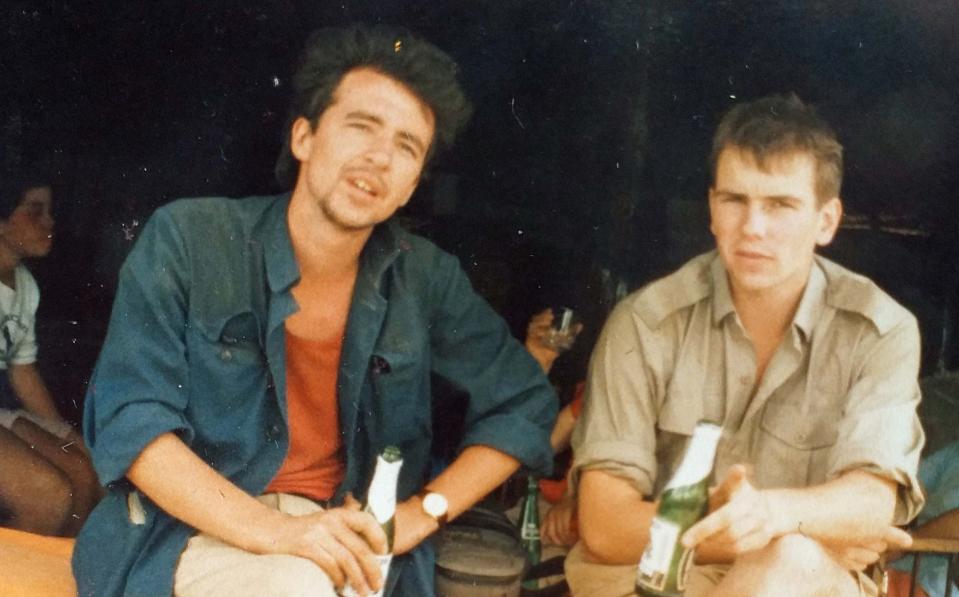

Beware the baboons, especially at breakfast. I had learnt that while travelling round Kenya in 1986 with a fellow law student, Roger. We were there for three months and had little money. In Nairobi, we had paid £110 each to join a camping “safari”. The bus had overheated about every 10 miles, and there was nothing to eat but bread and beans.

The baboon moment still stands out. Those animals had known exactly what to do. While our group was distracted, they stormed the kitchen tent. I can picture them now: 20 raiders, belting through the bunchgrass with a packet of bread under each arm. Roger and I did nothing to stop them. This was partly because we were now lying on the ground, helpless with laughter.

Thirty-six years later, I decided to return to the Maasai Mara. It would be a very different trip. Back then we had been given a bucket and an old army tent, and had woken up covered in ants.

This time we would be with Great Plains. Owned by film-makers and photographers, the company has made an art form of safari. Expect antiques, sculpture, goat’s cheese and craft gin. Every camp is like a Claridge’s-in-canvas.

The clientele was different too. In 1986 we had been thrown together with all sorts of backpackers (including some newlyweds and an Australian who had so many diseases we called him “The Germinator”).

This time, it would be just me, my wife and our teenage daughter Lucy. As we boarded our little safari plane, I noticed that Lucy was looking thoughtful. She had obviously seen my photographs from 1986.

I was also wondering about the Mara, and how it had changed. Things looked healthy enough as we whirred down the Great Rift Valley, over that fabulous crack in our planet.

But since I was last there, Kenya’s population had more than doubled (from nearly 21 million to almost 56 million). Nairobi, meanwhile, was five times its previous size and my old corrugated-iron hotel (which had doubled as a brothel) had long-since disappeared under concrete and glass.

How had the animals survived all this? And were the grasslands now covered in cities?

I soon realised I needn’t have worried. From 10,000ft, the savannah looked as pristine as ever. I have always thought England would have looked like this before humans arrived with their hedges and roads. It was green and luminous and endless. Small wonder that everything wants to be here, in this enormous salad.

Over the next five days we would see literally thousands of animals filing in through the hills – zebras as far as the eye could see, and trails of wildebeest looking like ants.

Humans have made little impression on the landscape. At the airstrip, there was nothing but a dustbin, a set of horns and our guide, Stephen. He turned out to be a remarkable companion.

Although the national park is the size of Hertfordshire, Stephen knew not only every gully and great beast but also all the warriors and clans that wandered the plains. It helped that his father was a local chief who’d had 10 wives and 62 children.

At this point, two things happened. First, enormous animals appeared. In the Mara, there are always big grunty creatures in view or in earshot. This is a success story that just keeps getting better. Rhino poaching has been all but eradicated.

Meanwhile, across Kenya, there are now more than 36,000 elephants, 12 per cent more than in 2014. That is why there is always something huge on the landscape – or heavy breathing in your ear.

The other big development was hospitality. Great Plains knows how to perfect a moment. Things turn up just when needed: powerful binoculars, a gin and tonic, or a collapsible washbasin.

Like all Maasai, Stephen enjoyed being a host. As a teenager he had worked as a herder, fighting off lions. Now he liked to drive our Land Cruiser in among the prides, introducing the cats as if they were family or friends.

All this was merely a prelude to the splendour to come. Our first camp, Mara Expedition, felt magnificently Victorian. It was as if some eminent delegation had marched up over the plains, bringing everything with them: chandeliers, rugs, leather armchairs, gigantic cabin trunks and campaign desks.

They had even brought their plumbing, and every tent had a colossal brass shower. Only the animals were unimpressed, and, at night hippos and giraffes would mooch through the grounds as if we didn’t exist.

Our second camp, Mara Plains, took all this to extremes. It had a tree-top library, a spa, a drawing room, two suspension bridges and a stretch of river. Arranged along a walkway of recycled railway sleepers, this was no ordinary glamp-site but a tented stately home. Every suite had a terrace and a giant copper bath. One of these pavilions, the Jahazi, was so vast and aristocratic it would easily have swallowed an orangery or a couple of ballrooms.

The staff were always splendidly attentive, in their khaki drill. Whenever we arrived or departed, they would line up, Downton Abbey-style. But they could also be chatty and charming. Amos the waiter was horrified by the thought of snow, and by the fact that we didn’t have our own herd of cows.

Robinson, meanwhile, had a spear and looked after us at night. Then there was Timothy the chef. He would conjure the most gorgeous dishes (pomegranate salad, perhaps, or passion fruit sorbet). How does he produce such things, out there in the wilds?

One night, we had a little earthquake. Way off, hippos grunted and lions groaned. In the camp, however, few of us woke – and the only sound was that of botanical gin, as the bottles clinked together on the bar.

Five days shot by. I had forgotten how dramatic life on the plains could be. We would lose ourselves for hours in this great biological theatre. First, there might be a dainty cabaret of zebras. Then a lion would appear, like Coriolanus, his huge shaggy head matted with blood and flies.

We would see ostriches too, like soldiers in tutus. There were also little turns from the Ugly Five (hyena, warthog, gnu, vulture and crocodile). Most entrancing of all, however, were the cheetahs. Everything seemed to stop as they strode past, supermodel cool.

Here, it isn’t just animals vying for attention. Some of the plants look strangely religious, such as Euphorbia candelabrum; or just plain dippy, like the pyjama lily.

Then there is a character that could be from a pantomime called sticky purple mousewhiskers, and the so-called sausage tree which always makes you laugh. But it isn’t all about display. Some acacias communicate using pheromones, and their leaves will turn bitter whenever giraffes attack.

Once we came across a skeleton, dangling from a tree. “A wildebeest,” said Stephen, “killed by a leopard.” It was a reminder that savannah life is often short and not-so-sweet, and that everything is eventually eaten – even people (the Maasai leave their dead out to be collected by scavengers).

I was still trying to process this idea when Timothy appeared in his white chef’s hat. He had set up tables by a waterhole and laid them with linen and china. “Welcome to Saltlick,” he said. “Full Kenyan breakfast?”

Before leaving, I asked if I could visit a village. Stephen drove me over to a circular compound with a thick stockade of thorn. It was called Ole Polos (“Between the Streams”) and I recognised the name.

It was funny to think the boys I had seen in 1986 were now warriors and chiefs. But, unlike their fathers, they no longer carried weapons or sold things made of skins and horn. There was also much less rubbish than I remembered (in 2017, Kenya banned single-use plastic bags).

Apart from that, little had changed in the last 36 years, or the last 5,000. Construction was still considered women’s work, and all the houses were made of branches and dung. The diet hadn’t changed much either; still blood and milk and a bit of meat. The Maasai also have a different attitude to rustling because they believe that all the cows in the world belong to them.

On our last morning, the baboons appeared. “Oh no,” I thought, “here we go again.” But they didn’t ransack the croissants or raid the prosecco. Instead, they merely scrambled over the library and into the treetops, in search of monkeys and figs.

That is typical of the Mara. Every day is different. Sometimes the hyenas win, sometimes the jackals. Elephants look gigantic one moment, vulnerable the next. Once we even saw a flock of guinea fowl mugging a leopard.

With such untainted beauty, the Maasai Mara remains as appealing as ever. Naturally, I don’t miss the buckets of my youth (and I loved the copper bath and the tented palace). The drama of it all is still utterly compelling. I don’t even mind what animal action I am watching, whether it is the “Big Kill” or the mongoose show. It is enough simply to be there, on that extraordinary, infinite stage.

John Gimlette travelled as a guest of Mahlatini Luxury Travel (028 9073 6050; mahlatini.com) and Great Plains (020 3150 1062; greatplainsconservation.com. A six-night holiday including four nights at Mara Expedition Camp and two nights at Mara Plains costs from £5,500pp, based on two sharing. The price includes international flights from London, all internal flights, transfers, plus all meals, drinks and scheduled daily camp activities.