Keith Baxter obituary

All good actors have stories to tell, but few related better or more affectionate tales than did Keith Baxter, who has died aged 90. An intimate colleague and friend of Orson Welles, Tennessee Williams, Elizabeth Taylor, Noël Coward, Maggie Smith and Joan Collins, he was laden with perceptive comments about all of them.

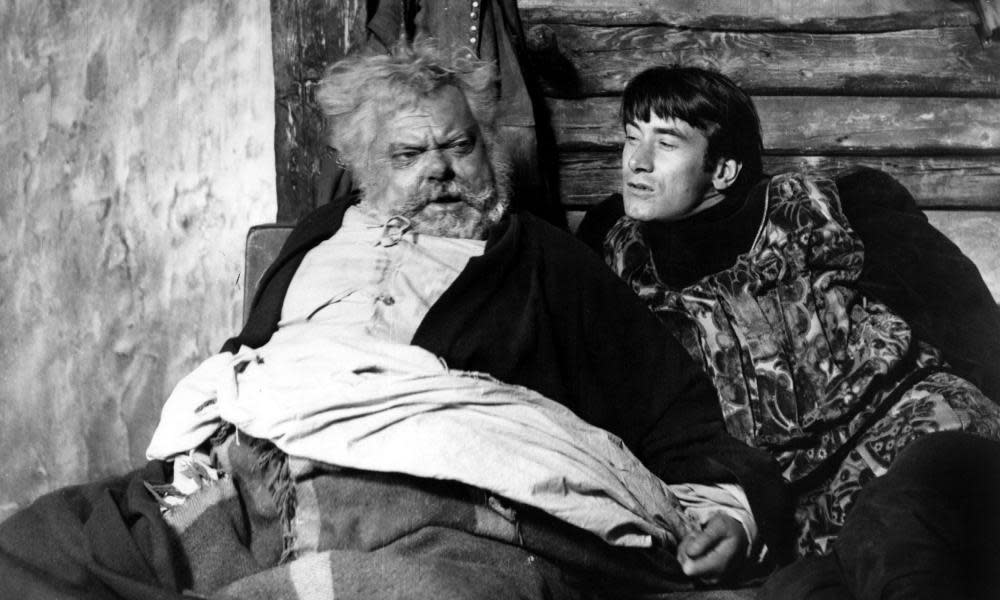

His pivotal professional experience was playing Prince Hal to Welles’s Falstaff in the latter’s celebrated conflation of both parts of Shakespeare’s Henry IV, Chimes at Midnight, first on the stage in Belfast and Dublin in 1960, then in the movie of the same name in 1965, one of the best Shakespeare films of the last century.

Welles matched his cinematographic genius – black and white, shadows, angles, misty lighting, stark settings – with a detailed closeup of character not only in Baxter’s febrile Prince Hal but also in John Gielgud’s tortured Henry IV, Jeanne Moreau’s slatternly Doll Tearsheet and Margaret Rutherford’s Mistress Quickly, all chins aquiver.

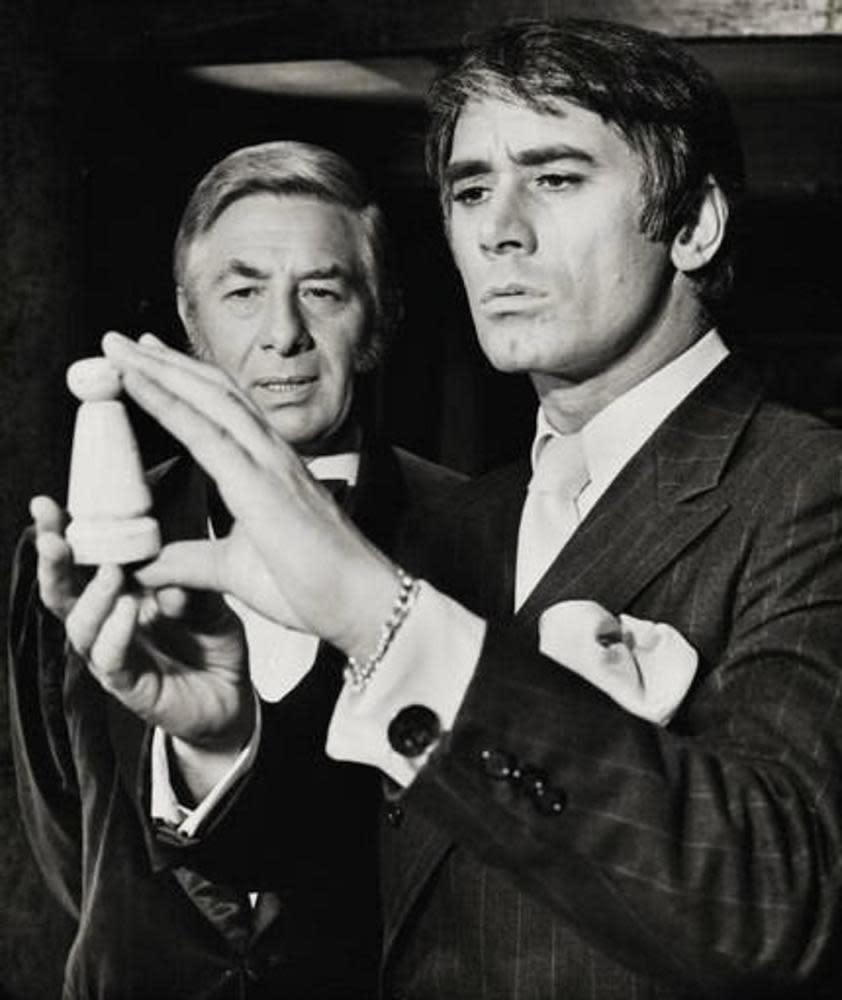

Baxter’s other big triumph was in Anthony Shaffer’s subversive, brilliant thriller Sleuth (1970), first in London, and on Broadway, with Anthony Quayle, later with Paul Rogers. He had already starred on Broadway in 1961 as Henry VIII (opposite Paul Scofield) in Robert Bolt’s A Man for All Seasons; this was when he first met Williams, linking up once more – this time romantically – when Sleuth went to New York 10 years later.

Baxter was born in Newport, in south Wales, the third child of Emily (nee Howell) and Stanley Baxter-Wright. Keith was educated at Newport high school and, when his father, a manager at the docks, was promoted to the position of pier master in Barry, Glamorgan, at Barry grammar school. Keith was set on becoming an actor from a young age and duly went to Rada in London, completing a year’s national service in Korea in between the two-year acting course. In 1956, he was awarded the Rada bronze medal and a contract with HM Tennent, the leading West End management firm of the day, worth £10 a week.

His first job that year was in film, in Sidney Franklin’s less good remake of his own The Barretts of Wimpole Street (1934) – this time with Gielgud (instead of Charles Laughton), miscast as the abusive, tyrannical father, and Baxter playing one of his children alongside Virginia McKenna and Maxine Audley, both of whom he found enchanting.

He went straight into rep seasons in Oxford and Worthing before touring in 1957 as a butler in Coward’s Pacific Island comedy, South Sea Bubble. This led to a London stage debut in the same year as an American footballer in Robert Anderson’s controversial comedy Tea and Sympathy, banned outright by the Lord Chamberlain because of its homosexual undertow, and performed under club conditions at the Comedy theatre (now the Harold Pinter).

Chimes at Midnight played at the opera house in Belfast and the Gaiety in Dublin, under the auspices of Hilton Edwards and Micheál Mac Liammóir, but the production was beset with mishaps, often descending into such chaos that Welles had to replace it with readings from Moby-Dick and the Bible. A projected international tour with a season at the Royal Court in London was dropped.

Baxter flitted straight on to Bolt on Broadway, returning to London to play Gino Carella in a stage version of EM Forster’s Where Angels Fear to Tread (1963), which started at the Arts and moved to the St Martin’s. Again, Baxter made a close friend and correspondent of Forster, staying in touch for the last years of his life and visiting him in his rooms in King’s College, Cambridge.

After filming Chimes at Midnight, he completed the 1960s on a high, joining a company led by Ralph Richardson at the Haymarket to play Valentine in George Bernard Shaw’s You Never Can Tell, and Bob Acres – executing a little dance inspired by another good friend, Rudolf Nureyev – in Richard Sheridan’s The Rivals.

Thence to Chichester, where in 1969 he made the first of several appearances as the devious, lubricious seducer Horner (inviting ladies in to inspect his china collection) in Wycherley’s The Country Wife (Smith was Margery Pinchwife), and as Octavius Caesar in Antony and Cleopatra (played by John Clements and Margaret Leighton, with Hugh Paddick as a hilariously drunken Lepidus).

He played Benedick in the Royal Lyceum, Edinburgh’s 90th anniversary production of Much Ado About Nothing in 1973 and joined Smith in a 1976 season at Stratford Ontario, under the direction of Robin Phillips, as a brawny, muscular Antony to her Cleopatra and a lady-killing Vershinin in Chekhov’s Three Sisters, Smith as Masha, in a production by John Hirsch rated by many the best they had seen.

Back in London, at the Roundhouse in 1977, he co-directed and starred in The Red Devil Battery Sign, a late play by Williams that has not settled into any agreed pecking order in his work. Baxter delighted Williams with his performance, in which he offered glimmers of salvation for himself as an unemployed musician, King Del Rey, and Estelle Kohler as a loud-mouth southern alcoholic simply labelled Woman Downtown.

He played a second Antony, opposite Judy Parfitt’s Cleopatra, in a 1982 Young Vic production by Keith Hack full of energy and movement. Corpse! (1984) by Gerald Moon was billed as a sophisticated thriller in the Sleuth or Deathtrap class but – despite a virtuosic display by Baxter as twin brothers, one planning to bump off the other to purloin his dosh and given to shoplifting in Fortnum & Mason disguised as the old Queen Mary (the year is 1936) – was flaccid, unfunny and worse than embarrassing.

His time as an actor in the theatre had gone, really, but he roused himself for an assault on Coward’s Private Lives at the Aldwych in 1990. His partner in crime in this jewel of a sardonic comedy was Collins, who came across as a vulgar chatelaine, while Baxter huffed and puffed as though he were her amanuensis, or chauffeur. “We were both too old,” was Baxter’s sorry excuse.

Instead, he turned to writing plays and directing thrillers at Chichester and in the West End: Cavell (1982), written for Joan Plowright at Chichester, was a moderately successful biographical study of the heroic first world war nurse Edith Cavell, executed for sheltering British soldiers in German-occupied Belgium; while Barnaby and the Old Boys (1989) at the Vaudeville was a domestic drama and a Welsh Christmas homecoming for the son who turns up with Barnaby – his Canadian black doctor boyfriend.

Baxter directed Patrick Hamilton’s Rope at Wyndham’s in 1994; JB Priestley’s Dangerous Corner with Susan Penhaligon, Gayle Hunnicutt and Christopher Timothy at the Whitehall in the same year; and, in 1995, Hamilton’s classic Gaslight, with Jane How and Frank Finlay, in the theatre at Richmond where the play first appeared in 1938. Also at Chichester, in 1998, he made a sentimental, possibly misguided, return to Chimes at Midnight on stage, this time as King Henry IV, with Tam Williams as Prince Hal and Simon Callow a gruffly Wellesian Falstaff.

There was a final act of wonderful self-mockery in his appearance as a glorious old ham actor in Bertolt Brecht’s The Resistible Rise of Arturo Ui, at Chichester and the Duchess in London in 2013, hired by Henry Goodman’s sensational Ui to give him lessons in deportment and “electrocution”. His last stage appearance, before the Covid-19 pandemic, was in a Hamlet in Washington DC, where he posed a triple threat as the Ghost, Claudius and the Gravedigger.

Outside Chimes at Midnight, his film career was negligible, though he wrote beautifully about the experience of making Ash Wednesday (1973), in which Liz Taylor, married to Henry Fonda, gets a facelift – although she was only 40 at the time and still ravishingly beautiful – and then has an affair with a beautiful young man played not by Baxter, but by Helmut Berger.

Baxter was by then spending more time in America. On a 1979 visit to Williams in Key West, Florida, he had met the restaurateur Brian Holden, and sustained a loving relationship with him for the rest of his life. They were married in 2016.

Plans to move to Long Island changed when Baxter realised how much he enjoyed living in the Chichester area while working on Cavell in the 1980s. So he sold his townhouse in Islington, north London, and decided instead on a lovely property in Selsey, West Sussex, where he and Brian spent the next 12 years. In the mid 1990s, they moved to Bosham, just outside Chichester.

He was predeceased by his sister, Christine, and brother, Tom, and is survived by Brian.

• Keith Stanley Baxter (Baxter-Wright), actor, director and writer, born 29 April 1933; died 24 September 2023