Julie Christie’s AI baby from hell: the prophetic horrors of Demon Seed

The rise of AI technology over the past couple of years has filled countless column inches. Writers, scientists and philosophers all have their opinion about the apparently inexorable progress of computer-generated intelligence in our lives, and most have concluded, solemnly, that if it is not checked or balanced in some way, that it might represent a Very Bad Thing indeed.

This may well be true, but if any of them had seen Donald Cammell’s 1977 cautionary sci-fi horror Demon Seed – a truly one-of-a-kind collaboration between mainstream genre filmmaking, a much-respected novelist and the altogether wilder sensibility that Cammell represented – they would be struck by how visionary, even prophetic, many of its once-ridiculed ideas now seem.

By the mid 1970s, Cammell was occupying a precarious position in the filmmaking firmament. He had initially trained as an artist, winning a scholarship to the Royal Academy aged only 16, and had made his film debut as a director almost by accident with the psychedelic, experimental gangster film Performance. The picture attracted a disproportionate amount of attention for both its casting of Mick Jagger as a bohemian rock star and for its heavy quantities of sex and violence. The studio that financed Performance, Warner Bros, had expected a light-hearted comedy, somewhat akin to the Beatles’ A Hard Day’s Night, and were appalled by what they saw instead. Notoriously, one studio executive’s wife was said to have vomited in shock at the first preview.

Performance was not a financial success upon its initial release, but it established the career of Cammell’s co-director Nicolas Roeg, who Cammell swiftly fell out with. (As he later said: “Nick went onto several features on the strength of Performance, and when you realize that the whole project was based on my friendship with Jagger, and the fact that Jagger trusted me, it does aggravate an already open wound. Enough said.”)

Roeg directed such zeitgeist-defining pictures as Walkabout, Don’t Look Now and The Man Who Fell To Earth, while Cammell was left in his slipstream, trying and failing to develop several projects with the ever-mercurial Marlon Brando, who – almost uniquely in 1970s Hollywood – believed that the director was a genius. Yet eventually an opportunity came to Cammell that seemed both compelling and unusual, and that would allow him to harness his visual talents with a suspenseful and chilling story. It might even make money, he thought.

Demon Seed, as it was known, was based on an early novel by the thriller writer Dean Koontz, published in 1973. Koontz subsequently described it as being written when he was “very young and stunningly, breathtakingly ignorant”. Its central narrative involved a woman, Susan Harris, being an initially unwilling and eventually terrified prisoner in her own home, held hostage by a sentient super-computer, Proteus IV.

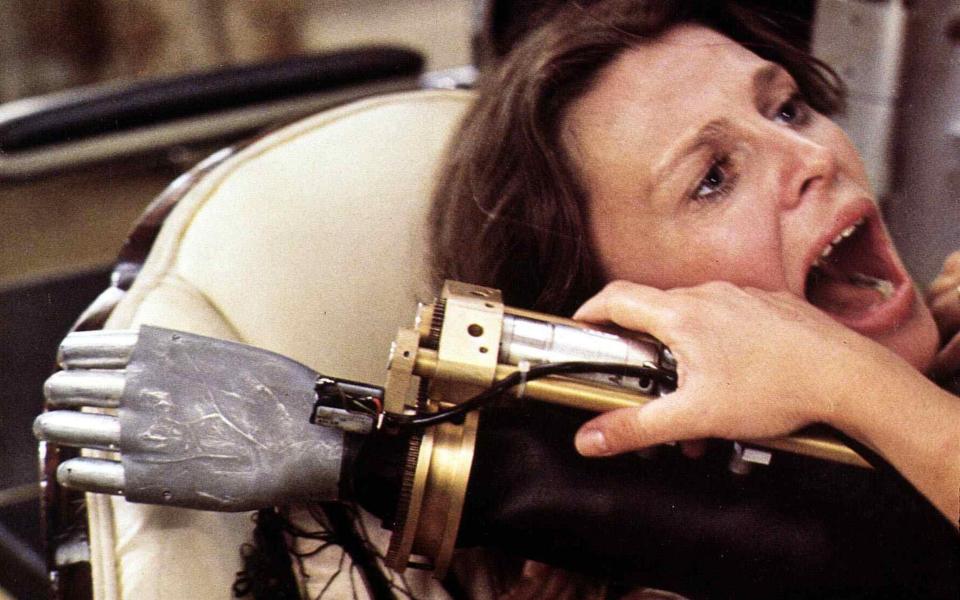

Proteus has the most sinister of carnal designs on Susan, facilitated by the mechanised home that her estranged scientist husband has built for her. One minute the thing is curing leukemia, the next it’s forcibly disrobing her with mechanical arms before threatening to murder countless human children. The novel attracted no particular attention when it was published, and Koontz even disavowed its title: “I think it sounds as if it’s a novel about a house of prostitution for the living dead,” he said.

Nonetheless, it was adapted into a screenplay by actor-turned-writer Robert Jaffe and produced by his father Herb. Cammell was brought on board purely as a director-for-hire, with no input into the script – the only one of his films that he did not write – and was candid about his motivation for taking the job. As he later said in an interview: “If you only knew how many unrealised projects are littered between 1970 and Demon Seed, you wouldn’t ask. One of those projects that caused a bit of a stir on the Riviera was a ‘caper’ screenplay entitled Avec Avec, which was made much later by my old mate James Coburn. This was the kind of luck I had up until Demon Seed.”

However, the perversity of the central relationship appealed to him. As his widow China Kong later said: “The story was basically a love story between a computer and a woman, and he loved that idea.” Cammell was responsible for the casting of Julie Christie – who, coincidentally, had appeared in his old collaborator Roeg’s Don’t Look Now four years earlier – and wished to use his psychedelic and expressionist directorial style in order to bring the battle of wits between Christie’s captive and the Robert Vaughn-voiced Proteus IV to life.

He assembled an impressive crew, including Jaws cinematographer Bill Butler, special effects veteran Glen Robinson and his regular editor Frank Mazzola, who he had worked with on Performance and had perfected that film’s non-linear editing style, which would be hugely influential on a number of filmmakers and music video directors over the coming decades. Yet just as he and Roeg had had an unhappy experience working with Warner Bros on Performance, so the demands of a big studio movie (in this case, one financed by MGM) would tell on Cammell.

As China remarked: “It was meant to have a much lighter feel to it, not to have this ‘terrorised woman in a house’ feeling.” She said of her husband’s moods that “I remember Donald being excited in the beginning, [but] distraught during the shoot because of the constant interruptions of the studio people…his style of working was very confusing to the producers, because he always had a lot of chaos around him.”

At one point, the studio attempted to ask Mazzola to edit the film without Cammell’s input, but he refused, saying: “I can’t do that…then I’d be at odds with the producers because they’d think I wasn’t playing ball with them. But I’d say ‘The director brought me in. What do you think I’m going to do, betray the director?’”

When the film was finished – Koontz said of its makers that “throughout production and editing, studio executives expressed a high degree of enthusiasm even when they were not coked out of their heads” – there was an initial preview that appeared to go relatively well, and Cammell, Mazzola and the producers all seemed to be on the same page when it came to necessary changes. Then, when Mazzola arrived to edit the picture, the master copy – the workprint – was missing. He was horrified to discover that a team of editors were busily engaged in re-editing the film to the studio’s specification without either his or Cammell’s involvement.

This came as little surprise to the director, who had always had a low opinion of moneymen. He later said that “it was a very unhappy experience. It was a pretty frustrating experience. My personality just does not gel with these studio people. And MGM was no different than Warner Bros was with Performance. I was the reason they got Julie Christie, who was red hot at the time, and an Oscar winner to boot. The front office loved everything until they got their hands on my rough cut. It could have been a great film, but even though it got bloody respectable notices, it wasn’t my vision. As I’ve said before, I am a painter who happens to make films.”

It did not help that the film’s central provocation, in which the Susan character is violently impregnated by the Proteus super-computer and later gives birth to a clone of her late daughter, speaking with the robot’s voice, was both near-the-knuckle in its depiction of mechanical sexual assault and liable to be used for prurient reasons in the film’s marketing.

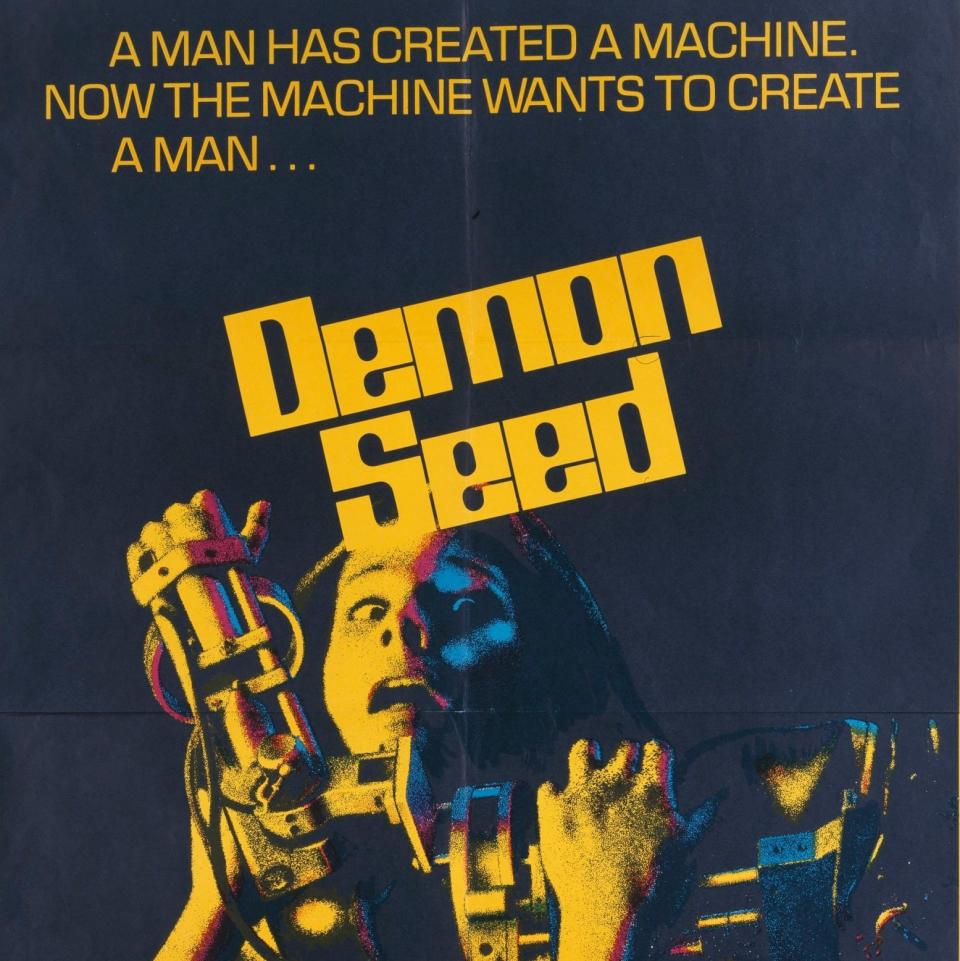

As Koontz pithily wrote: “[The studio] changed the initially classy poster and the stylish newspaper ads into a sleazy minimalist campaign to give the impression that the marvellous Julie Christie was appearing in a film produced by Larry Flynt, written by Harold Robbins while on 24/7 intravenous testosterone, and based on a banned book by the Marquis de Sade from his nasty period (as opposed to the period when he wrote books about cuddly kittens and puffy-tailed bunnies).”

In his inimitable description, as science fiction was not then seen as commercially viable, “they needed to sell Demon Seed as a sexapalooza, psycho-satanic, scare-your-pants-off (with an emphasis on pants off), see-Julie-Christie-naked, wow-wow sensation.” It did not work, not least because the film was blown off cinema screens by a small arthouse sci-fi picture known as Star Wars a few weeks later.

Four-and-a-half decades after its initial release, Demon Seed remains a little-seen cult film, admired by Cammell and Christie completists but otherwise obscure. Koontz rewrote his novel in the late Nineties to include considerably more humour – “I kept my tongue so firmly in my cheek that I needed the assistance of a periodontist to return it to the natural position,” he explained – and in 2001 it inspired a Simpsons episode in which a sentient home voiced by Pierce Brosnan has designs on Marge.

Yet the original film remains not just chilling, but prescient. In an era where AI can imitate human language, speech and thought to increasingly indistinguishable effect, and where so-called “smart houses” can be controlled either by a single touch of a button or by voice control – and where Amazon’s Alexa is a feature in virtually every household – it no longer seems that unlikely that a Proteus-esque computer might develop its own sentient desires. Although, admittedly, ChatGPT is yet to develop the ability to impregnate anyone.

Cammell and Koontz may have been disappointed by the film’s reception, but its nightmarish visuals – the Proteus “birth scene” especially – aren’t easily forgotten. In its loopy, prophetic horror, Demon Seed hints at less a brave new world of technological advance and more at a very real dystopia that we may already have unwittingly blundered into, even as we congratulate ourselves on our brilliance. And that, surely, is the most terrifying thing of all.