Jonathan Franzen's 'Crossroads' Might Be the Least Fashionable Book of the Year. So Why Is It so Hard to Resist?

Ancient History, Part One

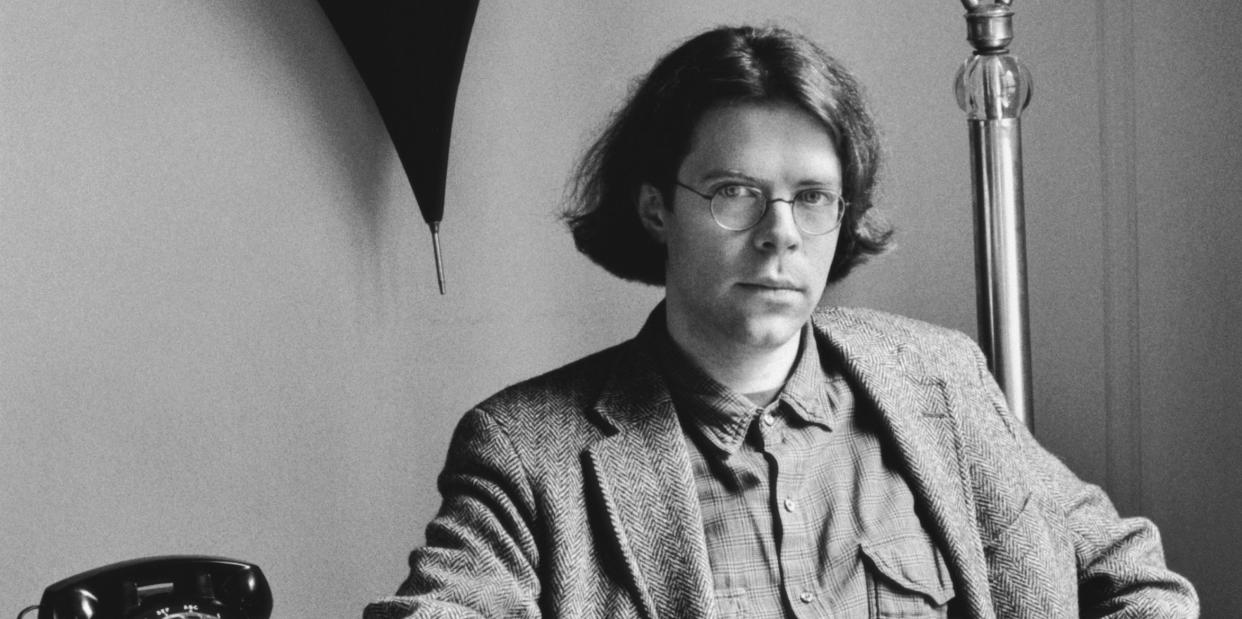

Twenty-five years ago, a young American writer, very serious indeed, author of two precocious novels admired by critics but ignored by the so-called general reader (who is this shadowy figure?) announced, in an essay for Harper’s magazine, that his national literature was in need of a saviour. A saviour from what? From the baroque perversions of postmodernism. From the blind alleys of academe. From the fissure between the hifalutin literary world, with its noodly experiments in form and structure, and the humble book shopper, with her preference — so basic! — for old-fangled nonsense-like narrative and character development.

The public, argued this serious young American writer, pushing his owlish spectacles up his nose, had been short-changed — neglected! alienated! — by the flatulent windbaggery of the late-20th-century metafabulists: Barth, Gaddis, Pynchon, all that mob, and even the serious young American writer’s hero, Don DeLillo, to whom he had once been in thrall. Also by a new generation, such as the serious young American writer’s good buddy, David Foster Wallace, who that same year produced his corpulent behemoth, Infinite Jest, with its footnotes to the endnotes — the exemplar of what the super-critic James Wood called “hysterical realism”

Was the spreadeagled adoration of Foster Wallace’s sprawling, antic, superabundance of sentences not final evidence that the social realist novel was a beached whale that had blown its last? Not a bit of it, argued the serious young American writer. Readers still wanted stories with beginnings that built to middles that moved towards endings, novels set in concrete, objective realities, richly summoned, finely detailed, peopled by characters like ourselves, conjured into existence by authors who believed in novels being about something more than themselves, and other novels, who thought that literary theory was for campus lecture theatres, who encouraged suspension of disbelief, and promoted the nobility of the quotidian, and enough already with the ironic clever-dickery and the damnable, self-reflexive mucking about. Readers wanted to connect. They wanted books that revealed their own lives to them, over, maybe, 500 to 600 pages of densely packed prose. Domestic dramas, written in the close third person, allowing access to the innermost thoughts of their characters. Novels about dysfunctional families, strained relationships, disappointed parents and unhappy children and sexual indiscretions and feelings of inadequacy and nervous breakdowns, and the compromises and accommodations we must make to live in the world as it is today. What was needed was books about latte drinkers, for people who drink lattes.

But who would America’s storytelling saviour be, this heir to Tolstoy, this Flaubert de notre temps? None other than the author himself: Jonathan Franzen, aged 37, from St Louis, Missouri, floppy hair grazing the collar of his serious young American writer’s tweed jacket. It was an exceptionally bold and bumptious promise and, five years later, Franzen delivered on it with a thumping, character-driven, social-realist, state-of-the-nation novel of late capitalist anomie that has been consistently rated at or near the top of the polls of the best books of the 21st century — “so far”, as they say, the muggles.

The Corrections was published in the US on 1 September 2001. Ten days later the planes flew into the World Trade Center and the Pentagon. Not even the most spectacular event in American history since the moon landings (so far) could steal Franzen’s thunder. If anything, 9/11 enhanced the reputation of his novel. Its tone of creeping anxiety and insidious disaffection was regarded as eerily prescient, as if Franzen, seer-like, had anticipated the attacks and their aftermath, and the toll they would take on ordinary Americans.

The Corrections is an intimate epic, the story of a middle-class family, the Lamberts, told from multiple perspectives. There are three grown-up children, all now living on the East Coast, each one approaching crisis: Gary, a rich, insecure banker; Chip, a struggling screenwriter; and Denise, a bisexual chef. Back home in the Midwestern suburb where they grew up, their father, Alfred, is succumbing to Parkinson’s disease. Their mother, Enid, is fixated on getting them all back together for one last family Christmas. Put that way, it doesn’t sound like much of anything, but the book was a sensation. It sold more than three million copies — a staggering amount for a literary novel — won the National Book Award, and it made its author, for a time, the most fêted American novelist of his generation, and certainly the most famous.

It is, I think, almost impossible to conceive of a novel — a novel! —creating similar excitement today. No, not even one by Richard Osman. I interviewed Franzen in late 2001, for the Evening Standard. The interest of the British popular press in a long and complicated novel by a previously obscure author from Missouri was not altogether a matter of intellectual curiosity. Franzen hadn’t merely written a literary bestseller, he’d conformed to garret-dwelling archetype and in the process created a myth: it had taken him nine years to complete The Corrections, working mostly on a second-hand computer in a tiny Harlem apartment, discarding “thousands” of pages in the process. At times he was so blocked, so easily distracted, that he took to blindfolding himself and plugging his ears while writing. He also drank a lot of vodka. (Who wouldn’t?) All these biographical factoids, too, became central to the story of the book’s success.

He didn’t stop there. Most confoundingly, and notoriously, the donnish Franzen became embroiled in a feud with, of all celestial beings, Oprah Winfrey, after she selected The Corrections for her book club — a career-defining anointment for most writers, from someone non- Americans might reasonably think of as a daytime chat-show host, but whose compatriots venerate as a demigod — and he publicly questioned whether this was a good look for him and his serious book, deriding her team’s other choices as “schmaltzy”. (They later made it up, kinda, at least enough for her to choose his next novel for her book club.)

Contrary to his reputation for grumpy smart-arsery, the Franzen I met way back when was almost painfully polite — the phrase “pardon me” was employed so often as to seem like a tic — but he was also guarded. When I suggested that the title of The Corrections might reflect his desire to, um, correct the mistakes made by other novelists — I meant DeLillo and Foster Wallace and the rest — he came on like (2001 simile alert!) a Donald Rumsfeld press conference: “That is something I will neither confirm or deny.” I mean, fair enough, but it’s only a book.

I asked him, as you do, about the autobiographical aspects of the work. “None of the book is my life,” he said. Then: “Of course, I could just as easily answer, ‘Every word in the book is my life.’ The emotional landscape — the pattern of the strong father who suddenly deteriorates — is something I’ve been through. I’ve seen how a family responds, or fails to respond, to that kind of crisis. And I’ve been in a troubled marriage. I know what it’s like to have siblings. I mean, people don’t write in a vacuum. Everything is from somewhere.”

The Corrections, those who read it discovered, was something more interesting than a routine family saga. Neither was it quite a traditional social-realist novel in the high Victorian mode; Franzen had hidden a number of esoteric deviations from the plot under the hood of his jalopy. As well as telling the story of the Lamberts, The Corrections investigates psychopharmacology, biotechnology, high-finance, Eastern European politics and cruise ships. You might almost call these diversions postmodern. “I want,” Franzen told me, “to be a kind of diplomat, shuttling back and forth between a certain kind of modernism and older-fashioned realism.” He got his wish. It worked.

Franzen’s follow-up to The Corrections, published in 2010, was another breeze block of social realism. Freedom returns to the Midwest, its author’s psychic terrain, if no longer his home (he lives in California), for the story of another middle-class family, the Berglunds: Walter, a middle-aged executive in the middle of a midlife crisis. Patty, his wife. Their friend, and Patty’s lover, Richard Katz, punk-singer-turned-alt- country-troubadour. (2010, remember?) Plus the Berglund kids, and the Berglund parents and siblings, all, to varying degrees, damaged and disappointed, despite their outwardly privileged existences in the land of, oh go on then, the free?

Like The Corrections, Freedom enjoys the liberty of frequent digression: avian conservation, mountaintop removal mining (heroically boring), the gentrification of America’s inner cities, the war on terror and the perils of late capitalism. And like The Corrections, Freedom ranges far and wide in space and time: suburban St Paul in the late 1970s; contemporary Washington DC; hillbilly West Virginia. Its most daring departure from the preceding novel was to have large sections presented as the autobiography of Patty, the most compelling character, apparently written at the urging of her therapist. Freedom was greeted by salivating reviews. The New York Times described it as “galvanic”. (Steady on there.) Franzen’s face appeared on the cover of Time magazine above the headline “Great American Novelist”. The book’s sales couldn’t measure up to those of The Corrections (no novel’s sales could) but it was still a resounding commercial success.

I suppose it’s remarkable, in hindsight — it’s certainly sobering — to remember that there was a time, not so long ago, when a middle-aged, middle-class, heterosexual, cisgender, able- bodied white man could dominate bestseller lists with a series of cat-killers about the first-world problems of straight, white, cisgender, middle-aged, middle-class, able-bodied Americans — and not just get away with it, but be roundly celebrated for it on the books pages and the chat shows and the prize-giving podiums. Not that no-one cried foul at the time, but their yelps were mostly drowned out by the riotous applause and the beeping of the check-out tills.

Writing in the London Review of Books earlier this year, the novelist Lauren Oyler noted that the cruellest tribute you could pay to a writer of fiction today would be to compare their work to that of Jonathan Franzen: “Among young writers online, this is more controversial than any sex thing you can come up with.” (She went on to note that the reason the comparison occurred to her while reading the book under review was because of its “careful rendering of emotional detail, and sweeping narrative arc.” I mean, how dare he?) It’s hard to know exactly when, or even why, it started, but the internet has developed a fixation on Jonathan Franzen. Not in a good way. He has been deemed, by the online Gauleiters, “problematic”: a lightning rod for generational resentments between zoomers and boomers.

It’s not only Oprah whose buttons he has pushed. The former lead book critic of The New York Times once called him a “jackass”. (Hey! What happened to “galvanic”?) An instinctive contrarian, he has managed to enrage environmentalists, feminists, the timeline commentariat and apparently everyone under 40, fulminating against the “totalitarianism” of the internet, and the “protection racket” of social media.

It is, of course, entirely possible that he is every bit as irritating as his online antagonists would have us believe. In a revealing 2018 profile for The New York Times (“Jonathan Franzen Is Fine With All of It”, by that beady-eyed hellion, Taffy Brodesser-Akner), he declined to describe the woman he lives with as his “partner”, saying he hated the word. I’m with him on that, who isn’t? Partner is a dreadful term, and only ghastly people use it. Franzen, he told Taffy B-A, prefers “spousal equivalent.” Gah! Is that a joke made deliberately to annoy? Or is he serious? And wouldn’t that be even worse? But then, who cares? You don’t have to live with the guy, only read his books — or not!

Mostly the animus stems from the fact of his gender, and to a lesser extent his ethnicity. And while there is no suggestion that I’ve seen of personal toxicity — he is hardly Mailer, or Roth, or Updike, or Bellow (feel free to add to this list) — and in fact he has often been praised for his sensitive treatment of female characters — Enid in The Corrections, Patty in Freedom — it is nonetheless an incontestable fact that he is a straight, white, middle-aged man, yadda yadda, and no one, it is often said, wants to hear from them (us) right now.

“There is no way to make myself not male,” Franzen told Emma Brockes of The Guardian, in 2015. (Forgetting, perhaps, that there is one way, and lots of people get very angry at any suggestion that there isn’t, but that’s not what he meant. Not that it matters what he meant. Or does it? No. Yes. No. Fuck you. Etc.) In order to appease feminist critics, he told Brockes, “there’s a sense that there is really nothing I can do except die — or, I suppose, retire and never write again.”

Franzen spoke then of being “hurt” and “ashamed” by the opprobrium heaped on him. One could forgive him for wondering, sometimes, how come Jeffrey Eugenides doesn’t cop this shit, and who gave Ben Lerner a free pass? But he seems a resolute sort of stick. And I suspect that the idea that might interest him more about the position he finds himself in — totemic exemplar of a divisive figure: white male novelist — is that it has very little to do with the kind of novels he writes, and everything to do with the kind of person who writes them. Franzen’s critics aren’t angry because his work is not postmodern enough. They’re angry because his success, in their judgement, takes up space that could be used by writers who are not white cisgender men.

Franzen was mistaken, then, in that Clinton-era essay, to suggest that the future of the novel would be the conflict between form and content, avant-garde and middlebrow, postmodern and premodern. The correction required turned out to be not one of literary approach, but identity and representation. It wasn’t that readers required more realism or less realism, it was that they needed more books by black authors, and women, and the many, many other groups under-represented on publishers’ lists and in book club selections.

It is easy, today, to make a list of, say, the 10 most significant novelists to achieve mainstream recognition in the past 20 years without including a single white guy. So I will: Colson Whitehead, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, Rachel Cusk, Junot Díaz, Zadie Smith, Paul Beatty, Elena Ferrante, Viet Thanh Nguyen, Jennifer Egan, Sally Rooney. And it wouldn’t have been so easy before 2000. Some of those write social realism, others don’t. That’s not the point. Middle-aged white men haven’t been put off entirely — Hallo, Karl Ove Knausgård! — and Franzen certainly hasn’t. In 2015, he published Purity (“piercingly brilliant”: The Observer), another door-stopper, this one almost-but-not-quite a departure, in that it wasn’t wholly concerned with the detonation of a nuclear family. By the time we meet the novel’s heroine, Purity, who goes by Pip (nudge, nudge) her family is long splintered. Hers is a quest to discover the secret of her disputed parentage. It brings her into the orbit of a dangerous, Julian Assange-like online evangelist, Andreas Wolf, offering Franzen much scope to rehearse his anti- internet arguments.

Purity didn’t achieve anything like the level of cultural penetration of Franzen’s previous two megahits — again, whose novel did? — but it did contain some of his most entertaining swipes at, as ever, pathetic middle-aged white people, most enjoyably a paraplegic creative writing professor cuckolded by his younger wife, the comic-satiric aspect being the most often overlooked aspect of Franzen’s writing by those who seek to traduce him. In its lavish over-plotting and occasionally madcap tone, Purity, more than anything Franzen had published since the 1990s, seemed to owe a debt to the exuberant postmodernism of Pynchon et al, the so-called “systems novel”. But flawed human relationships and the question of how to live now were still its central concerns.

Writing in The New York Times in 2010, Franzen had declared that the purpose of novels, “and only novels”, is to tell the inner story of family life. Or, he added, grumpily, “it used to be.” Perhaps it could be again? Before we sigh and offer a jaded “Good luck with that, JF”, it turns out Franzen has more to say. Really quite a lot more.

Ancient History, Part Two

Fifty years ago, in a suburb of Chicago called New Prospect, there lived a family, unhappy in its own way. Russ Hildebrandt was a clergyman, an ordained minister of the First Reformed church. He was also a typical thwarted middle-aged man: financially strapped, professionally stuck, sexually frustrated. Marion was the clergyman’s wife, older and smarter than he, but damaged in ways he didn’t know about and couldn’t have imagined. She was also an archetype: weight-watching, middle-aged housewife, disappointed in her marriage to a bore who might even be shading into a creep. There were four kids: straight-arrow college boy, Clem; popular high-school hottie, Becky; druggy boy genius, Perry; and even-tempered little Judson, whose defining characteristic (apart from the even temper) was that he was nine.

Crossroads, Franzen’s new novel, arrives as the first book in a projected trilogy entitled “A Key to All Mythologies”. And, in case you were wondering, yes, the Middlemarch reference has riled as many kombucha-gulping Eng lit types as it has caused gleeful others to hug themselves with passionate self-love, before tapping out and refilling their pipes. (“A Key to All Mythologies” is the title of the hopelessly engorged, and mind-numbing — also unfinishable — magnum opus of George Eliot’s insufferable Mr Casaubon.) Crossroads, then, is part one in a generations-spanning saga of a family, and the family, specifically the American family.

When we meet the Hildebrandts, they are smarting from a scandal at the church youth group that gives its name to the title of the book. Blundering Russ and his wandering eye have been exiled from Crossroads following a mortifying showdown with some of the perkier teenage girls, who much prefer the charismatic ministrations of Russ’s arch enemy, the preening phony Rick Ambrose. (An echo of the dodgy past of Andreas Wolf, in Purity.) Russ’s fall from grace sets in train a series of crises, with each member of this conservative-alternative Midwestern family sent hurtling blindly to points far and wide: Russ and the woman with which he has become infatuated (and Perry and his stolen stash) on a disastrous trip to Arizona; Marion (and young Judson) to California, to be reunited with a man from her troubled youth; Clem to college, and then to New Orleans, and then to South America; Becky to Europe. There is some shuttling back and forth in time — most memorably, and incongruously, a lurid, almost Gothic flashback section in which we learn some hair-raising stuff about Marion’s #MeToo past, in noirish 1940s Los Angeles — but otherwise the story proceeds in a stately manner, Franzen’s mastery of plot and character and tone only very occasionally flagging (the Goth-noir stuff).

Crossroads is about faith, lust, envy, addiction, madness, the chasms between generations and even, a bit, the misunderstandings between people of different backgrounds and ethnicities. It is about attraction and repulsion; the word “repel” and its derivatives appear with such regularity you want to offer Franzen a cough sweet. Crossroads presents the members of the Hildebrandt family and their various intimates as a collection of magnets, pulling each other in and pushing each other away. It is possible, at least it was in my case, to feel the same way about Franzen’s book itself, to be both drawn in by it, as it hums along, and then, if not repelled, then certainly discouraged — by its length, its occasional clumsiness, and also, in 2021, when so much in our society does seem at stake, its triviality.

Certainly, as Lauren Oyler suggests, it might be the most unfashionable novel of the year, a nearly 570-page epic (part one of three, mark you) about the not-very-serious-really problems of some relatively comfortable white people half a century ago, with Franzen’s tin ear for modern cultural sensitivities much in evidence. There are brief appearances for poverty-stricken urban African Americans, during the novel’s excursions into Chicago, and poverty-stricken rural Native Americans, in the sections set in Arizona. No doubt the awkwardness of the meetings between the white protagonists and the people of colour is deliberate: Franzen is satirising the patronising presumptions of his decent, churchgoing folk. But it’s still the case that within the world of the novel, the minority characters exist to reflect back on the wealthier white characters their prejudices and preconceptions, as well as to highlight their philanthropic endeavours. African Americans and Native Americans, in Crossroads, are to be feared, or pitied, or romanticised, or admired, but mostly they are to be helped. The efforts of the white people to provide charity are mocked, but there’s no suggestion I could see that their hearts are ever really in the wrong place, even if, as in Russ’s case, he uses his charity work as an opportunity to get his leg over.

Franzen writes what he knows, from his position of white male privilege. Of course, to fully develop the minority characters, he would have to try to write from inside their heads, in their voices: very much a no-no in 2021. And so the Black pastor, Theo Crenshaw, and Russ’s Navajo connection, Keith Durochie, must remain ciphers. Such is our present predicament. The further I got into Crossroads, the more I began to wonder what I was reading, and why. Not because of my delicate sensibilities (I do believe they exist, and I promise I will never stop trying to locate them), nor because I am allergic to domestic melodrama (I’m not). It’s Franzen’s thing, and to find fault with that, on novel number six, would be like complaining about the lack of car chases in Penelope Fitzgerald. That wasn’t the problem. It’s more that while The Corrections in particular felt crisp and significant, Crossroads at times feels an odd combination of stodgy but weightless, like a day-old French fry. Reading it, I felt transported back to my own childhood, watching TV miniseries based on crass airport paperbacks: The Thorn Birds, in which a handsome priest in olden times falls for a sexy parishioner. Did Colleen McCullough’s reverend, like Franzen’s, have a huge cock? Wouldn’t know, haven’t read it... Probably.

Then — and yes I’ve been working up to this — there’s that title. It won’t be a consideration for Franzen’s American audience, but for British readers of a certain age (we’re a niche group, but, like embittered Midwestern suburbanites, we do exist) the title Crossroads will evoke most immediately is not the work of the legendary Delta bluesman who sold his soul to the devil in return for guitar genius unmatched until the arrival of, I don’t know, anti-vaxxer axeman Eric Clapton (whose cover version, with Cream, of “Crossroads” receives short shrift from crusty old Russ Hildebrandt), nor even the idea that in life there are certain moments when consequential decisions must be made. Instead Franzen’s title summons a long-running (1964-1988) ITV soap opera set in a Midlands motel, much mocked by the alleged comedians of the day for its wooden acting, cardboard sets, and paper-thin plots.

For all its faults, or even as a result of them — its most memorable character, indeed its only memorable character, was a “village idiot” called Benny, who wore a woolly hat — Crossroads the TV soap was hugely popular, drawing up to 15 million kitsch-loving viewers each episode. It was also regarded as socially relevant, tackling subjects controversial at the time for mainstream light entertainment: interracial romance; marital breakdown; the need to be patient with simpletons in silly headgear. (Still timely today!)

Franzen’s previous novels felt like contributions to a wider conversation about where society was at, and where it was headed. There is something less essential about Crossroads, a period piece about The Way They Lived Then: folk rock and the fug of doobies and afternoon infidelity. No doubt, through examining American society in the early 1970s, as a dominant conservative society begins to confront, and assimilate, the counterculture — a crossroads moment for the US, as well as for the Hildebrandts — Franzen is building towards a larger portrait of the shifts in public manners and private mores over the past half-century. But this time the stakes don’t seem so high.

Will randy Russ succumb to temptation and cheat on misery-guts Marion with foxy Frances, the flirtatious young widow who joins him on charitable trips to Chicago in his clapped-out Plymouth Fury? Will beautiful Becky steal hunky high-school heartthrob Tanner from his spiky girlfriend? Will pilled-up Perry get so banjaxed on uppers he manages to stop smirking for a paragraph? The motivations of the teenage characters seem frustratingly opaque. Why does clean-living Clem dump sexy Sharon, quit college and volunteer for Vietnam? Is it because he is somehow sexually attracted to his own sister? A potentially, ahem, fertile — if icky — plotline that is never quite developed. Or is it to break away once and for all from his embarrassment of a dad? More plausible but also… yawn.

And then there’s the other nagging thought, when after a longish break one confronts a novel such as this one: if it’s middlebrow, character-driven narrative fiction that’s required in 2021, we know where to go. Two years before The Corrections was published, The Sopranos had introduced the idea, developed over the following decades, that the small screen would be the medium through which the inheritors of the mantle of the realist novelist would do their work. If it was the new Dickens you wanted to be, prestige TV was the place to be. The great contemporary storytellers were showrunners, not novelists, and the venerable print-publishing houses had been replaced by video on demand.

Novels are analogue. Franzen is an analogue figure, and a maker of analogue products, living and working in a digital age. A stepson of the time, in Vasily Grossman’s phrase. This may be why Crossroads is not set in the present day. One suspects that the challenge of writing a novel located in the social media age, with characters who exist online as much as they do IRL — a challenge he accepted, to an extent, with Purity, but that has been taken up more recently, and much more enthusiastically, by younger novelists — is not for Franzen. Dude doesn’t even ’gram. (I look forward not only to Lauren Oyler’s take on Crossroads, if one is forthcoming, but also to Patricia Lockwood’s. And if no one has commissioned that yet, then I do wish she’d call.)

Franzen is 62 now. Presumably the next few years, maybe more than a few, are mapped out completing the trilogy that Crossroads begins. Perhaps, given the previous breaks between his novels, this will be his swansong. If so, whatever side you take in the culture wars, it’ll be hard to deny the guy has had a remarkable career. Halfway through Crossroads, I resolved to quit my Franzen habit once and for all. This would be my last hit. No way would I read the next part of the trilogy, whenever that appears.

But then, as with Crossroads’ Marion and her cigarettes and Perry and his cocaine, I’m always resolving to quit stuff that I subsequently take up again. Because whatever it is, the things I get unhealthily stuck on — fags, booze, long novels about the decline of Western civilisation refracted through the petty problems of middle-class strivers in America’s flyover states — I fucking enjoy them. I bitch about it, but I flew through Crossroads in a weekend, barely pausing to eat or sleep or swab my nose and throat, happy to be hooked once again by this brilliant writer’s near unmatched ability to get me under the skin of his indelible characters. Gah!

You Might Also Like