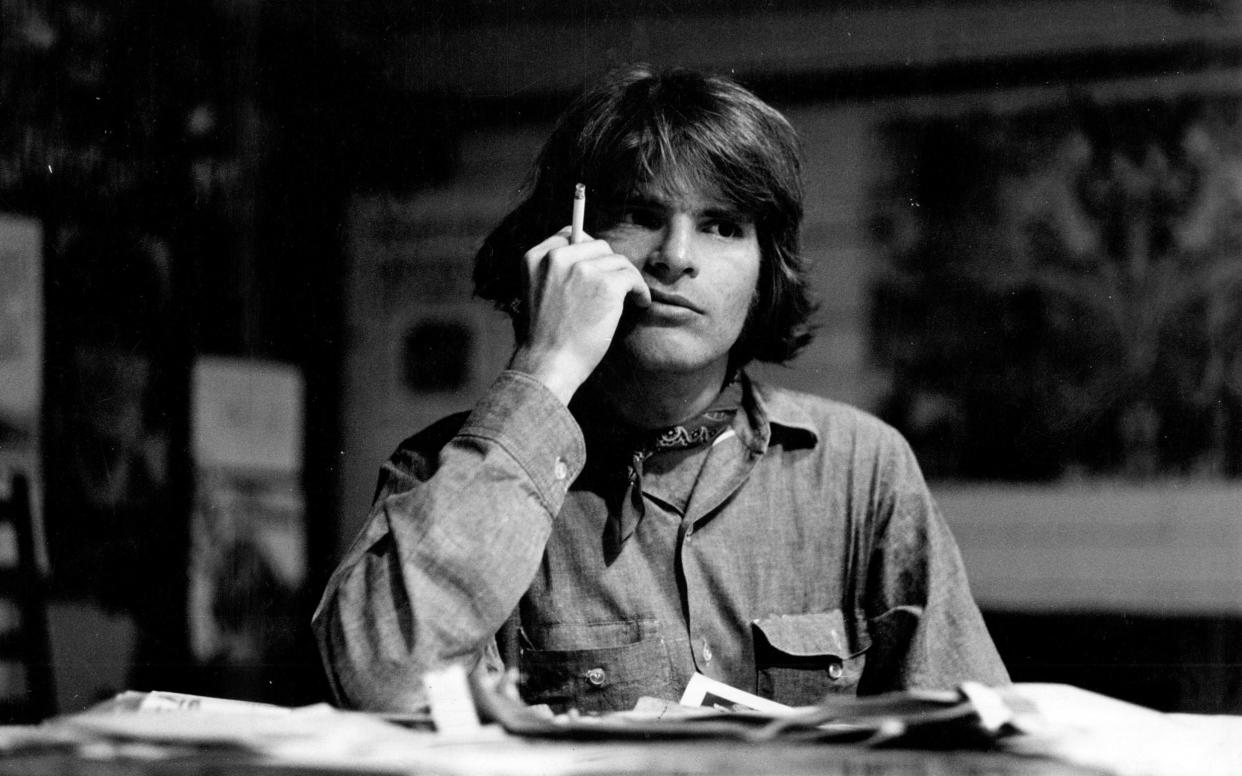

John Fogerty’s advice from Dylan: ‘Sing Proud Mary or the world will think it’s a Tina Turner song’

John Fogerty is aware of the paradox. At a time when musicians from Bruce Springsteen to Neil Young are selling the copyright to their song catalogues for eye-watering sums of money, the Creedence Clearwater Revival singer has just bought his back after a gruelling 50-year legal battle. Tracks such as Bad Moon Rising and Proud Mary – the 1969 song covered by Ike and Tina Turner as well as Elvis – are finally majority-owned by the 77-year-old after decades of wrangling with the band’s late label owner Saul Zaentz.

“It has been a lifelong pursuit,” Fogerty says of the “horrific” saga. “It’s ironic that in the age when it finally happened for me to own the majority stake in all my own songs, it seems like all my peers are selling theirs.” To reflect his “great sense of victory”, Fogerty is bringing his Celebration Tour to the UK. He will play solo – the band’s late guitarist (Fogerty’s brother Tom) died in 1990, while bassist Stu Cook and drummer Doug Clifford formed splinter group Creedence Clearwater Revisited. Fogerty says a full reunion is “impossible”.

But Creedence Clearwater Revival’s songs – swamp rock belters overlain with Fogerty’s growly howl – are growing in popularity. Have You Ever Seen the Rain?, their catchy 1971 hit, is one of just 417 songs to have been streamed over a billion times on Spotify, placing Fogerty in a club with the likes of Ed Sheeran. It has achieved this status without a Kate Bush-style Running Up That Hill TV sync deal. “I suppose there’s enough mystery in the lyrics and enough of a catchy melody,” Fogerty says, his modesty at odds with the voice that earned him the nickname Foghorn Fogerty.

Creedence Clearwater Revival formed as The Blue Velvets in the early 1960s in small-town California. The young four-piece band signed to tiny San Francisco jazz label Fantasy Records, which was soon acquired by Zaentz (also a successful movie producer who won Oscars for One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, The English Patient and Amadeus, and bought the film rights for Lord of the Rings). In awe of British Invasion bands like The Beatles and The Animals, the label changed the band’s name to The Golliwogs in the toe-curling belief that this made them sound British – they “hated” it and were unaware of the racial connotations, Fogerty says. “That name was settled on by the record company. They got it completely wrong because in this day and age that word is so utterly not PC. But it was not our idea.”

The band’s new name was a combination of a childhood friend (Creedence) and a beer advert (Clearwater), while “revival” nodded to a previous hiatus. The group honed a sound influenced by Deep South icons such as Jerry Lee Lewis and Bo Diddley, even though they’d never visited. The broiling, bluesy spirit came to Fogerty as he was hallucinating on a scorching parade ground as an Army Reservist (he was drafted). A cover of Dale Hawkins’s Suzie Q made Creedence famous but Proud Mary made them stars. Creedence played Woodstock, a “mixed blessing”, Fogerty says. Arriving at the festival, he wandered around incognito. “I remember feeling, ‘Oh boy, I hope this stays peaceful and everyone has enough to eat and enough water, because this could be a very bad situation.’ ”

What struck him was the lack of leadership both in the crowd and backstage. Creedence performed after midnight following The Grateful Dead (“lost in a psychedelic fog”). They refused to sanction their set’s use in the subsequent Woodstock film – they felt it lacked energy – and so weren’t immortalised in counter-culture’s most famous historical document. Fogerty doesn’t think they were paid either. “I never saw a cheque,” he says.

Despite being serious and driven, Fogerty did occasionally out-hippy the hippies. He recalls telling The Doors’ Jim Morrison about how nasty the world will be when the machines take over, and was surprised by his response. “Jim comes out with this, ‘Oh no, I think that humans will always be able to keep [the machines] in control.’ He had a very sunny way of looking at the situation. And he was the man who’d sung The End,” Fogerty says.

Creedence were flying high. In 1969 alone, they had five top 10 US singles and outsold The Beatles. But behind the scenes things were a mess. A punitive contract with Fantasy meant they received low royalty rates while Zaentz owned the music’s copyright. Further, the band contractually owed Fantasy a fixed number of songs annually. If they didn’t deliver, the figure rolled over into subsequent years. As Creedence’s songwriter, the burden fell on Fogerty. “I was going to have to make something like 20 to 25 albums,” he says, comparing the contract with “unending horrible legal slavery”. The naive band had trusted Zaentz: “We thought Saul was our best friend.” When the band split in 1972, decades of litigation followed.

Rarely in rock history has there been such animosity. Fogerty sued Zaentz (who died in 2014 age 92) and Fantasy, Zaentz sued him, the band and Fogerty sued each other. One of the most bizarre legal twists saw Zaentz sue Fogerty for writing a song, The Old Man Down The Road, that sounded too much like the Creedence song Run Through the Jungle, which Zaentz owned. Fogerty was being taken to court for plagiarising himself. He won the “absolutely ridiculous” case. “It shows that if you have enough lawyers and money, you could sue a chipmunk,” he says. “I was flabbergasted that I was sued for sounding like myself.”

In court, Fogerty realised the landmark nature of the case: it was about the right of an artist to protect their own work. “I could feel the memory of people like Shakespeare looking at this trial and going, ‘John, you better get this right otherwise bad people are going to be taking advantage of everybody,’ ” he recalls. He has expressed solidarity with Sheeran, who has on several occasions been at the centre of a US plagiarism suit.

The psychodrama caused Fogerty untold grief and left him unable – by choice – to play Creedence songs for 15 years. The hoodoo was eventually broken by Bob Dylan. In 1987 Fogerty went to a club in Los Angeles to see blues musician Taj Mahal perform. George Harrison and Dylan were also there, and an impromptu jamming session ensued. The crowd called for a Creedence song, and Fogerty refused – he didn’t do that any more. Then Dylan got involved. “Bob turns to me and says, ‘John, if you don’t sing Proud Mary the world’s gonna think it’s a Tina Turner song.’ His logic was beautiful. And this is Bob Dylan telling me. So, OK,” says Fogerty.

So all-American is Fogerty’s music that no fewer than four US presidents have come out as fans. Gerald and Betty Ford danced to Creedence at Ford’s inauguration, Bill Clinton wanted the band to play at his first inauguration (Fogerty declined), George W Bush was a fan of 1985 track Centerfield, and Donald Trump used the song Fortunate Son during rallies. This latter use resulted in a cease and desist letter from Fogerty. Still, four presidents. That’s his very own Mount Rushmore right there, I tell him.

Fogerty’s career hasn’t been easy – he’s clearly a perfectionist. And he says he’s always been an “old soul”, even when he was wandering the fields of Woodstock. He puts some of the “very young” band’s misfortune down to the lack of a decent manager to guide them (they approached Allen Klein post-contract, but he couldn’t help them, while Colonel Tom Parker, who went on to manage Elvis, was mooted). “I wish there had been a father figure or grandpa, someone to give advice. The fans would have loved an uncluttered career. But it just was not to be,” he says.

But that’s in the past now. Fogerty is, after half a century, Creedence’s fortunate son. And he knows it. “For me, it’s just a lot of fun to enjoy this.”

The UK leg of John Fogerty’s tour begins tonight; johnfogerty.com