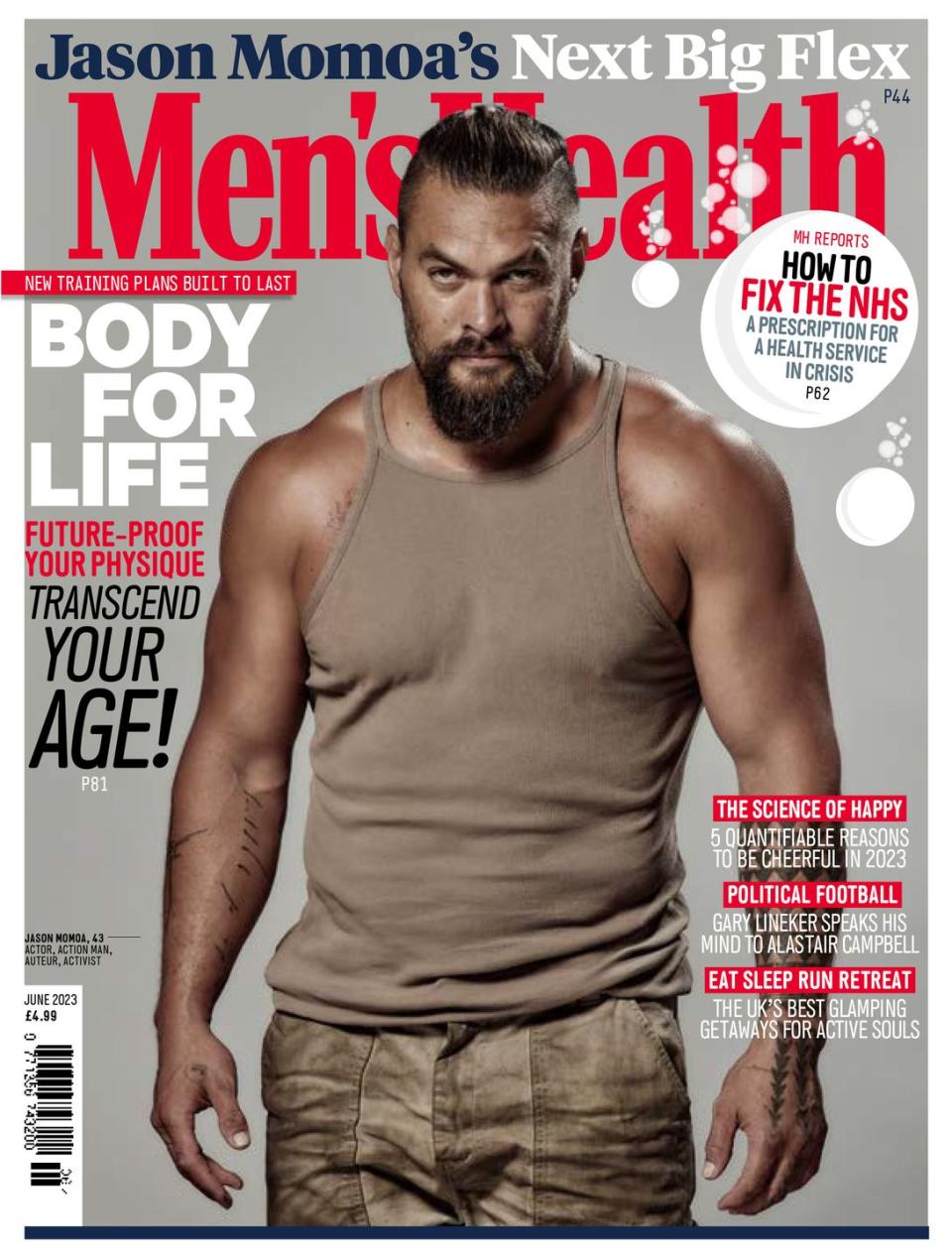

Jason Momoa's Next Big Flex

JASON MOMOA is a hard man to pin down.

Momoa is a little more than halfway through an eight-month shoot in Aotearoa/New Zealand for an Apple TV+ show called Chief of War. Momoa cowrote, codirects, and stars on the nine-episode series, which tells the quasi-historical story, from an Indigenous perspective, of a Hawaiian chief in the late 1700s who tries to unite the warring islands in order to save them from the threat of colonisation.

When we finally connect by Zoom after some serious wrangling, it’s midnight in New York and 5:00 p.m. Kiwi time; his assistant hands him an iPad as he walks off the set after wrapping an epic scene, which explains why he’s wearing only a malo (a traditional Hawaiian loincloth) and a shit-eating grin with a swollen top lip. He uses a wipe to clean his sweaty face; dabs different members of the crew; and after lots of “Love you, bros” and “Love you, dudes” is ushered into a car that will whiz him back to his base camp in Auckland while we talk.

Even from 9,000 miles away, his energy slams like a chest bump. He leans forward and starts talking about the day’s shoot, his green eyes blazing and his new head tattoo giving texture to his dome. He’s both a fast talker and a serial mumbler, and his words and sentences sputter, then gush out, forming fast-moving stories.

“I’m trying to figure out what I can and can’t say, but my character, a chief called Ka’iana, traveled to a foreign land to rescue a friend. It’s like a prison riot, people hanging, people falling from the ceiling. There’s musket shots and fires everywhere, just burning chaos.” He sounds kind of like Stefon from SNL talking about the world’s hottest action movie. “It’s a beautiful wonder we pulled it off and no one got hurt. I’m pretty high off that. All I got was a bruised lip. Ka’iana is helping free people who have been enslaved, and he’s witnessing for the first time poverty, drugs, and it’s the first time he’s seen a dog, a rabbit, a peacock. He’s experiencing with new eyes the whole world.”

Momoa, too, is experiencing with new eyes the whole world. Now 43, he’s in a different place—professionally, emotionally, and literally—than he was when MH last caught up with him, in 2020. Careerwise, he’s conquered the blockbuster with the billion-dollar-grossing Aquaman, the brightest star in the DC Universe; held his own among an A-list ensemble in Dune; and carried three successful seasons of See on Apple TV+. This month, he plays the villain in Fast X, the much-hyped final ride for the Vin Diesel–powered franchise, and the sequel Aquaman and the Lost Kingdom drops on December 20.

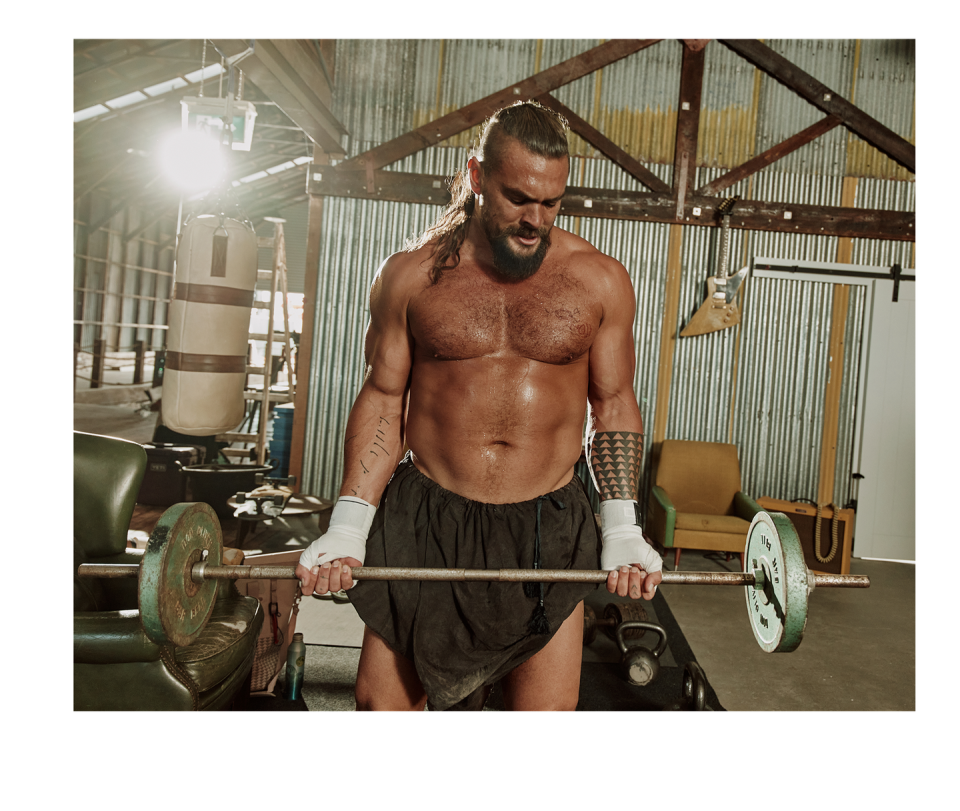

He’s also dealt with some major events in his emotional life. In January 2022, he separated from Lisa Bonet, his partner of 16 years (and wife of nearly five years), as well as the mother of their two children, Lola, 15, and Nakoa-Wolf, 14. (Before the interview, he made it clear he doesn’t want to get into the nitty-gritty of his personal life, and we don’t really blame him.) Two months later, he underwent surgery to fix a hernia injury sustained during the Aquaman 2 shoot and joked that he couldn’t do sit-ups anymore, describing himself as an “ageing superhero.” (But in our Zoom, there’s no sign of the dad bod that set off Twitter trolls last year.)

That June, he was named the UN Environment Programme’s Advocate for Life Below Water for his activism with Sustainable Coastlines Hawaii and rePurpose Global and for his fight to ban single-use plastics. And that September, he spent two hours getting a traditional Hawaiian tattoo on the left side of his head. He tells me it’s his favourite ink, symbolising protection for his family and his aumakua, which in Hawaiian means “guardian spirit”; the triangle pattern represents a shark.

Now he’s living in Auckland, pouring his heart into his work for the next year or so. (After Chief of War, he’s shooting an undisclosed blockbuster-to-be there.) He’s nesting in a duplex warehouse surrounded by the things and people helping him be creative: his own kettlebells and boxing gear, his vinyl, his guitars, his mountain bikes, his vintage Land Rover, and a fridgeful of packs of poi (a Polynesian snack made from taro root, bananas, or pineapple mixed with coconut cream) and cans of Guinness, plus a chef, a trainer, a Hawaiian-language teacher, and a squad of artistic collaborators he’s worked with for years at his production company, Pride of Gypsies.

Momoa is aware that his career orbit is in that high stratosphere where his name is the green light for a project. “Now it’s wonderful, because it wasn’t handed to me. It was a very, very, very hard road,” he says. “For a good 20 years, no one knew who I was. I worked on TV shows and wanted to be on something better.” Now he has power and a platform to make a difference through his storytelling and activism. He doesn’t want to waste it. “I gotta help the world. This shit weighs on me.”

WHILE FILMING DUNE in Budapest four years ago, Momoa pitched Chief of War to Apple with producing partners Brian Mendoza and Thomas Pa’a Sibbett. He says he wanted to tell this story for a very long time, but he had to wait until his career was at a peak, because of the costs and because he wanted the control to direct, produce, and act in it.

During our interview, he calls it his “holy grail,” “my baby,” and “my dream.” He’s prone to hyperbole and known for being super enthusiastic, but this really means a lot to him. “It’s like my Braveheart or Dances with Wolves,” he says. “I never thought it would be this big. It’s the hardest, most challenging, most demanding thing I’ve ever done. It’s the last big dream I have left. Everything else is just kind of ‘actor for hire,’ but this is my homage to my people. We have so many beautiful stories in Hawaii that no one knows about. All I care about is just doing right by my people.”

Momoa adds that the series is also “for Indigenous kids growing up, understanding that we were warriors and what we come from and understanding there was a language that was stripped from us. Like most Indigenous tribes, everything’s taken from us. It’s like rebuilding and building these bridges back.” The first two episodes are entirely in Hawaiian, Mendoza tells me, and he believes it’s the largest Indigenous series ever made. The show is written by Hawaiians, and the majority of the cast members are Hawaiian and Polynesian. Three episodes were shot in Hawaii and the rest in New Zealand, which has bigger studios and better 360 degree vistas with visibly fewer tourists. “There’s a massive responsibility to Hawaii and the culture,” says Mendoza. “Even though we’re not making a documentary, we’ve gone to great lengths to ensure what people see is historically and culturally appropriate.”

Mendoza, who calls Momoa his best friend, first met the actor in 2008. They bonded over a shared love for Julian Schnabel’s The Diving Bell and the Butterfly, a devastating movie about an editor’s heroic struggle to communicate after he suffers a stroke. They started working together in 2010, when the two coproduced Momoa’s feature-directing debut, the 2014 Native American drama Road to Paloma. He says Momoa has long had an inner fire and wanted to be a director. “Jason’s always been a nonstop workhorse who sleeps a few hours a night and whose mind is always racing,” Mendoza says. “I think Jason knows this is a rare opportunity, and he’s grabbing it by the horns because this moment may not last forever. We hope that with this show it opens doors for other filmmakers to tell stories of underrepresented cultures.”

When asked what’s the most surprising thing about Momoa, Mendoza says it’s his talent as a director. “He has a creative eye and he’s so visually focused, but also so story driven. He has the ability to spot performances and work with actors. And he’s never, never had an ego. Sure, he knows what he wants, but he’s very collaborative.”

Momoa directed the finale of Chief of War, which he shot in Hawaii. Again, he doesn’t want to spoil anything, but he tells me that it is historically based and involves two forces battling on a black lava bed, with two actual volcanoes actually erupting. Upon the crew’s arrival to shoot the final episode of season 1, Mauna Loa and Kilauea were erupting together for the first time in about 40 years. “We paid our respects and we did it right,” he says. “There are so many spirits and things we’re stirring up—and I believe in that. We shot it all at dusk and at night with four units. It’s crazy to think that two volcanoes went off while we shot a story about two volcanoes going off. Wow! It’s probably the highlight of my career.”

FOR MANY ACTORS, playing the superhero in a billion-dollar-grossing movie would be the highlight of their career. And in some ways, Aquaman—and its sequel (and a rumoured sequel to the sequel)—is for Momoa. But not for the reasons you might think. “Well, to be perfectly honest, I was absolutely baffled that Aquaman was received so well,” he says. (The movie was appreciated more by audiences than by critics.) “I’ve done things that are amazing that no one sees and no one gives a shit about. You just don’t know in this business.” He’s quick to add, “I don’t go do things and think, Oh, I’m gonna get $1 billion on this one. I go in and do my best job.”

Momoa’s feelings about Aquaman—frustration, bitterness, apathy—are less about the character and more about how the character has been treated. “It’s not that I don’t care about Aquaman; it’s a wonderful character,” he says. “Aquaman is probably the hardest character in comic-book history. He’s made fun of and ridiculed, but I tried to give it heart and soul, and I’m proud of it in certain ways. Do I feel pressure for [the sequel] to do well? No. All I can do is give it my all. But it’s in a lot of other people’s hands.”

He’s referring to the turbulence of “different directors having different ideas of who Aquaman is” (Momoa has played Aquaman, aka Arthur Curry, in three other movies in the DC Extended Universe) and, more specifically, to the 50-page treatment he and Mendoza wrote for the sequel that he says Warner Bros. bought but did not follow completely. That bugs him and spins him into an impassioned, salty riff.

“That’s the reason why I love directing and creating. At the end of Chief of War, I’m like, ‘Yeah, feel free to knock, ridicule it. If it isn’t good, then we suck. It’s our fault.’ Yeah. I don’t wanna just go like, ‘I’m acting. I’ll be in my trailer.’ I love being able to burn for what I believe in. I’ve seen some of the most shocking acting performances firsthand and watched them edited, and they were amazing. I wish I could tell you who it was. I’m like, ‘What the fuck?’ I watched this guy who had to be fucking propped up. They read the lines to him. But this motherfucker killed it when the edit came in and was applauded for it. At that point, I was like, ‘Wow, this shit is made in the edit.’”

There’s new leadership at DC Studios: co-CEOs Peter Safran and James Gunn. Safran, who produced Aquaman and the sequel, is a big Momoa fan. “What you see is what you get with Jason,” he says. “I have been working with him for six or seven years, and I keep waiting for the proverbial other shoe to drop. If there is an inner asshole in him, it has never come out. That, to me, is a surprise . . . albeit a very pleasant one.” Momoa says he’s “extremely, extremely excited” about his DCEU future but won’t divulge any secrets other than “there’s a lot of badass shit coming up.”

Safran, who probably wrote the secrecy memo, adds: “I look forward to working with Jason for many years to come. I would be happy for it to be in Arthur Curry’s world, but if/when another opportunity came up, I’d find another great character for him to create.”The bar is set high, because, as Safran tells me, “there are few superhero castings that are more perfect than Momoa as Aquaman.” He explains how Arthur Curry is the ultimate outsider: He doesn’t believe he’s part of the surface world or Atlantis and has never felt a true sense of belonging in either. Momoa was born in Hawaii but moved to Iowa after his parents divorced when he was six months old, and he grew up with that sense of “otherness” that led him to discover, like Arthur does in the films, that not belonging anywhere makes him belong everywhere. And, of course, Momoa is deeply connected to the natural world—and passionate about protecting it.

He is a fierce advocate for banning single-use plastic bottles. “We’re just killing our planet. We’re choking our planet out. Why the fuck are you drinking out of a plastic bottle of water? It’s crazy, ’cause it’s easy to change. Like drink a can of Coke, beer, or sparkling water.” Momoa is quick to add that you should get a purifier or Brita in your home and carry a reusable bottle. But he was so infuriated by seeing plastic bottles of Fiji and Dasani at airports that he started his own company, Mananalu, selling purified water in recyclable 16-ounce aluminium bottles (available on Amazon and at Whole Foods).

His status as eco-warrior, elevated by his role as Aquaman, enables Momoa to make a difference. He says it’s a calling from deep, deep in his soul, his mana. “It’s my kids’ generation, and they’re looking up to me, going like, ‘You’re Aquaman, you’re Aquaman.’ I’m not fucking Batman or Superman. That’s really cool to me—it really is.” It’s not all easy. Momoa recalls how fearful he was when he first spoke at the United Nations about banning single-use plastics, in 2019. It was terrifying for him to stand up in front of the whole world—and have his own kids watch him trying to make that difference. “I couldn’t chicken out of it and try to do some fake stuff. I practice what I preach. Get up there, say what’s important, and fight,” he says.

Momoa believes in the ripple effect, and he’s giddy when he tells me that Harrison Ford, a fellow eco-activist, recently sent him a letter to applaud his conservation work. (“Han Solo! Indiana Jones! Bro!”) What Ford wrote about—gulp, the meaning of life—resonated with him. “He said he’s been doing conservation work for 30 years, and he says it’s the most positive work he’s been doing.” It’s an outlook Momoa shares. “It’s really cool to be up here as an actor, but this is not what I wanna do for a living. It’s just a moment in time. I wanna go back to making art, to painting, to writing, you know, raising a family, and then making significant environmental change. I’ll do movies just to entertain.”

THAT BRINGS US screechingly to Fast X, and a reminder of why so many people care about Momoa: He’s the stallion who mounts the world, a larger-than-life kicker of ass. In the movie, he plays Dante, a villain out for revenge following the death of his father at the hands of Dom & Co. in Fast Five (2011). Momoa—a “huge, huge car and motorcycle fan”—came into the movie with his own ideas on how to be the best villain ever, but he felt privileged to join the franchise and wanted to collaborate with Vin Diesel and director Louis Letterier.

“I saw the first Fast and the one that was in Brazil [Fast Five], and they’re amazing—they always are,” he says. “I talked to Vin and said, ‘Yo, Daddy-o, I’m here to support you, but I’m going to do it my way. I’m going to be a bad man, and you’re going to want to take me out!’ It felt really good to go there without some ego competition, like, ‘Who’s this?’ and ‘Who’s that?’ I’m like, ‘No, dude, you got ten movies under your belt. It’s an honour to be here. I’m down to go down.’”

Momoa says Letterier and Diesel respected and supported his “weird and bold” choices, pushing him to bring more out of the character and giving him a safety net. “If I did something quirky that Louis really liked, he would be like, ‘Oh, can you do that again?’ No director has ever really asked me to do that.” The love goes both ways. “Jason brings the humour, the panache, so much pink, purple, and fuchsia, beautiful silk, and he’s not afraid to improvise and take risks,” Letterier says. “He’s also a fantastic action actor—he will perform all his stunts, he will ride his bikes, he will drive his cars, he will sing his own songs. He’s just a force.”

Vin Diesel also appreciated the energy Momoa brought to Fast X. “For the finale of this great saga we wanted to bring in a super interesting and formidable villain,"says Diesel. “It was important to create the space where Jason could feel comfortable to produce some great work, to flesh out his character in a way that supports a talent’s creative drive.”

Of course, Momoa being Momoa, he love, love, loved the motorcycle scenes. “I’m riding in Rome on a Harley ripping through centuries-old cobbled streets,” he says. “I had an amazing stunt double, Joe [Bucaro], and he did some cool stuff that would kill me. But the other half of the time, I’m riding at top speed through Rome—that’s me. I couldn’t believe Louis let me do it. He was like, ‘Wow, that guy really looks like Jason?’ They’re like, ‘That was Jason.’ And he’s like, ‘Are we insured to let him do that?’ And they’re like, ‘He just does this in his normal life—that’s what he does.’ It was surreal, dude. C’mon, bro.”

We’re nearing the end of our conversation, closer to the destination, when Momoa will get out of the car and return to his warehouse/artist commune. Maybe he’ll hit the heavy bag, pound some poi, throw back a Guinness, spin some vinyl, and watch climbing videos sent by his kids. “I make them send me clips all the time,” he says. “I’m watching my heart climb up the wall. They’re children, but they’re so strong and confident and express themselves through movement. Sometimes you have to be dynamic, sometimes static and smooth, and you just get to explore. When they succeed, you feel the moment. I absolutely love climbing and encourage any parent to go experience it with their kids. That’s what my mom did with me.”

Momoa’s origin story involves a lot of climbing. His mom introduced him to it as a teen, and it became his passion. He lived the dirtbag life, climbing in remote spots around the world, living off sardines and crackers; those experiences still inform his outlook. “Climbing is what keeps me grounded in a chaotic world that just wants more of me. It keeps me centred, keeps me in the dirt, keeps me humble, and keeps me stoked.”

He shares that passion with his kids, whom he communicates with twice a day. “That’s the thing I try to teach my children right now,” he says. “There’s nothing worth doing if it’s not gonna be hard and it’s not gonna be a struggle. It’s okay to fall. You fall, you get back up and do it again. They wanna be perfect and they’re afraid; they think if you fall, it’s bad. But I’m like, ‘No, falling is great, man. Falling is great ’cause you’re gonna succeed if you keep doing it.’ I would never teach acting, but the one thing I could teach is climbing. It gives us this massive bond, and we go outside and do it. It’s the ultimate thing for me.”

No doubt Momoa misses his family, but he also recognises this is the life he’s chosen. “I don’t get to see my kids right now for a very long time. I gotta share things with them,” he says, his rapid-fire speech pattern slowing way down. “I’m doing everything that I want to do, everything that I’m designed to do. And you’ve got to do that. I want my children to know that and do that. I worked for a very long time when they were young doing shit I didn’t want to do to put food on the table. And now? You should only work with the people you wanna work with. You should create with the people you wanna create with. And if you’re not, then you got one shot in this life—you gotta get the fuck out. Whatever situation you’re in, you gotta find your path, you know?”

This story appears in the June 2023 issue of Men's Health. Out now!

You Might Also Like