Fears prisons could be run by gangs as thousands of guards quit

The staffing crisis in UK prisons has been laid bare as new figures show thousands of the most experienced officers have quit the service, leaving jails vulnerable to increased violence, instability and control by gangs.

Analysis by The Independent shows that some 60 per cent of officers across UK prisons had more than 10 years of experience in 2017, but that figure had plunged to around 30 per cent by June this year. More than 1,000 of these more experienced prison officers have been lost in the past year alone.

At the same time, the proportion of officers with less than three years of experience has risen from 27 per cent in 2017 to more than 36 per cent.

Experts warned that inexperienced staff had less confidence to deal with violence and organised crime bosses on prison wards while being left without support or mentoring. Labour said the scale of experienced staff leaving the service was “frankly alarming”.

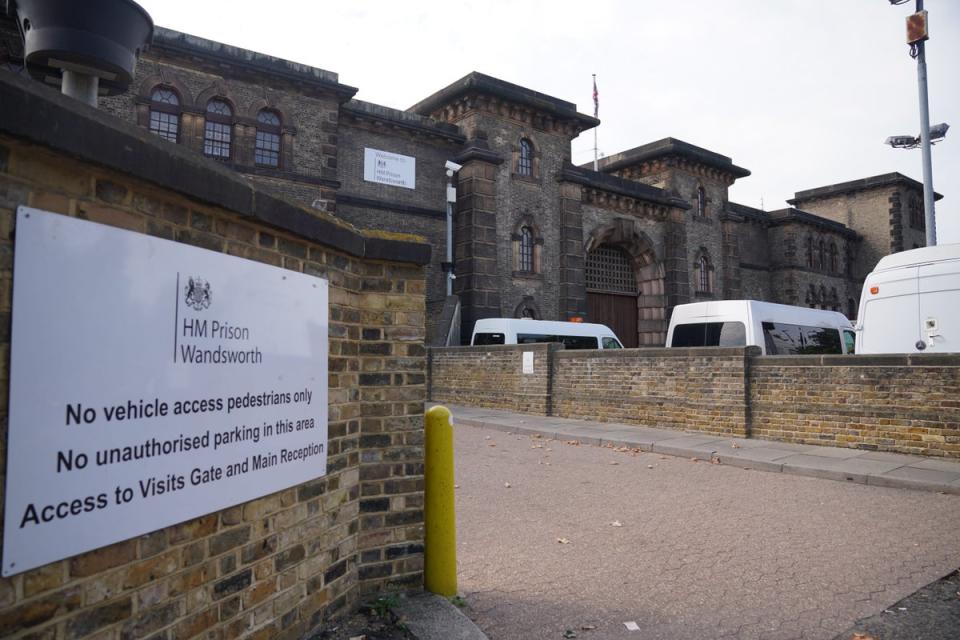

The figures are revealed as an investigation was launched into how terror suspect Daniel Khalife managed to escape HMP Wandsworth, with Charlie Taylor, the chief inspector of prisons, saying the single biggest problem facing that prison was a lack of experienced staff.

Mr Taylor also told The Independent that governors, prison officers and prisoners were concerned about “very inexperienced staff who just don’t know the ropes”.

“That’s fine if you’ve got one or two because you can mentor them or look after them. But we often come across instances where inexperienced staff are being mentored by those who are only slightly more experienced than them,” he said.

He said increased prison violence created a “vicious cycle” where staff wanted to quit, leaving the jail with less supervision, and causing violence to increase.

Steven Gillan, general secretary at the Prison Officers Association, said young staff were “being left to their own devices” without sufficient mentoring, which left them open to manipulation by organised gangs.

“These young staff ... 18, 19, coming in now, they’re not getting the same mentoring that I had. They’ve been neglected.

“You have prisoners who will manipulate that [inexperience] and suss out the confidence of staff and bully and intimidate them into their way of thinking, which is quite wrong.”

Andrew Neilson, director of campaigns at the charity Howard League for Penal Reform, said the loss of “so many experienced staff” was one of the key factors driving the “crisis” in prisons.

He said the situation had “created instability at every level of the system”, with “overstretched senior leadership teams in a state of flux while new staff with little training are parachuted in”.

Sir Bob Neill, a Tory MP and chair of the Commons justice committee, described the retention of experienced officers as a “problem”.

He said: “You have inexperienced officers on the wing and when problems emerge it is often the old hands who are better at calming things down.

“They have the experience, they have seen things before, and they can also be better at building relationships [with prisoners].”

There were over 11,100 prison officers who had served for 10 years or more in the service in 2017. This has now fallen to just 6,681 in the latest statistics from June this year.

The latest Ministry of Justice statistics from June show that prison officers with 10 years of experience or more make up just 29.8 per cent of staff, compared to 59.4 per cent in 2017. There are around 22,400 prison officers currently in the service.

The number of staff who have had less than three years of experience has also been increasing – 36.3 per cent of officers had less than three years of service in 2023, compared with 27.2 per cent in June 2017.

A survey by the committee this summer suggested that the lack of experience will only get worse.

Half of prison officers said they do not feel safe at work and over 40 per cent plan on leaving the service in the next five years. This is compared with around 30 per cent of operational support staff.

Mr Taylor said that where staff used to join the service in their mid-twenties after working elsewhere – such as in the armed forces – now some new staff members have only recently left school.

He issued an urgent notification for HMP Woodhill in Milton Keynes at the end of August after he found that the prison had the highest rate of serious assaults against staff in the country. The notice concluded that “the many relatively inexperienced staff lacked the confidence and were not sufficiently supported to challenge poor behaviour”.

Mr Tayor said: “If a prison is a violent and dangerous place then the [staff] drop-out rate will be higher, but then that feeds into a vicious cycle because provision gets less good and prisoners get locked up more.”

A 2021 report into Wandsworth prison found that “staffing shortfalls were preventing the prison from running a decent and predictable regime”.

“More than 30 per cent of prison officers were either absent or unable to work their full duties. Around a quarter were less than a year in post and more than 10 per cent had resigned in the last 12 months,” it added.

Mark Serwotka, head of the PCS union, said that Wandsworth was among those that had lost “years of staff experience”.

“That is a symptom of the decisions about austerity in 2010 that are really being seen now,” he told The Independent.

Shabana Mahmood MP, Labour’s shadow secretary for justice, said: “Thirteen years of Conservative mismanagement has led to staff shortages and unmanageable workloads in the prison and probation service. Morale amongst staff is in the depths of despair, and the rate of loss of experienced staff is frankly alarming.”

A Prison Service spokesperson said: “We are doing more than ever to attract and retain the best staff, including starting salaries for officers which have risen from £22,000 to £30,000 since 2019. Our hardworking officers are also being equipped with the tools they need such as Pava spray and body-worn cameras, and X-ray body scanners prevent the smuggling of illicit contraband that fuels disorder. These measures are working and in addition to increasing the number of officers by 4,000 since 2017, retention rates for prison staff are now improving.”