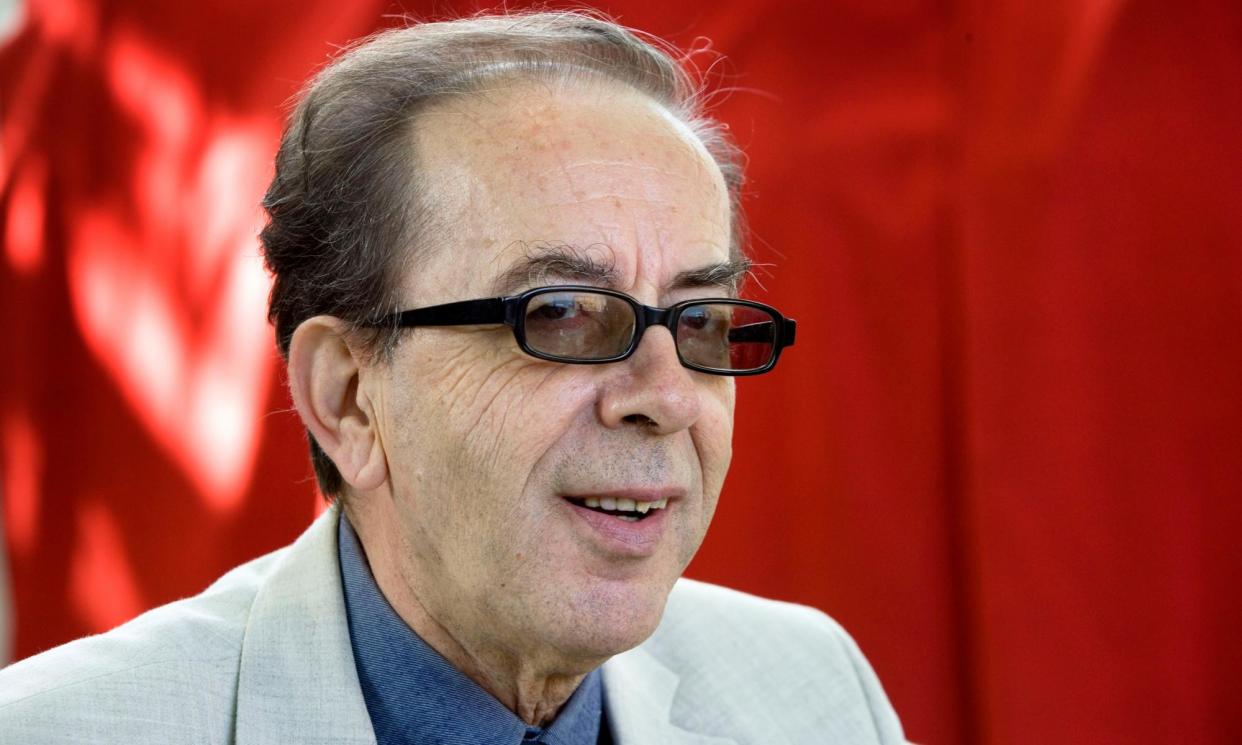

Ismail Kadare obituary

Ismail Kadare, who has died aged 88, was the best known Albanian writer of his own generation and all others, and one of the most remarkable European novelists of our age. He leaves a body of work as immense as Balzac’s Human Comedy, as unrelenting in its critique of dictatorship as Orwell’s, and as disturbing as that of Kafka.

Kadare’s 80-plus novels, stories, poetry collections and essays constitute a national monument, an invention as well as a reflection of what it means to be Albanian, an exploration of both the ugliness and the dignity of an ancient and oppressed nation. With him disappears Europe’s last indisputable national writer.

The son of Halit Kadare, a minor official, and Hatixhe (nee Dobi), Ismail was born and grew up in the walled city of Gjirokastër, which was also the home town of Enver Hoxha, dictator of Albania from 1944 to 1985. The city, its modern history and its strange atmosphere are recreated in Chronicle in Stone (1970) and elaborated in The Fall of the Stone City (2008).

Kadare was a brilliant student at Tirana University and already a celebrated poet when he was still in his teens. Albania was a Soviet satellite state at that time; Kadare was therefore sent to Moscow to pursue his literary education at the Gorky Institute for World Literature, which he attended between 1958 and 1960. What he learned there, he often said, was how not to write. The miserable weather of most of his novels, set in a country with a Mediterranean climate, was understood by Albanian readers as silent mockery of the sun-kissed wheatfields of socialist realist novels.

Hoxha broke off relations with the Soviet Union in 1960. Kadare was therefore able to write a fictionalised account of his Moscow years without risk. Twilight of the Eastern Gods (1978) nonetheless implies that something was rotten in the state of Albania too.

Kadare’s first published novel deals with the bizarre duties of an Italian general sent to Albania to gather the remains of soldiers who had fallen during the Italian occupation and the war against Greece (1938-43). The General of the Dead Army (1963) established Kadare’s reputation as a novelist. It also attracted the attention of Jusuf Vrioni, a former aristocrat educated in Italy and France, who offered to translate it into French. Vrioni went on to translate all of Kadare’s work until his own death in 2001, and his name cannot be separated from the story of Kadare’s career.

In the 1960s, communist Albania, which refused to be “de-Stalinised”, entered into an alliance with Mao Zedong’s China, in the middle of the Cultural Revolution. Kadare and thousands of other intellectuals spent months in the provinces among workers and peasants. However, his official position was that of journalist, and he was allowed to return to Tirana before the end of the decade.

In these early years, Kadare wrote a large amount of poetry, and most of his fiction consisted of short stories and novellas. Often, a poem would be rewritten as a prose story; sometimes, stories would be expanded or combined. Names, motifs and places recur from one story to another, linking them as fragments of an imaginary world.

Cross-references between different works are part of the arsenal of subtly hidden tools Kadare used to express opposition to the authoritarian regime of Hoxha. However, despite his fame and international recognition, he was not exempt from political discipline. In 1975, a poem denouncing bureaucracy (but indirectly suggesting that the party had blood on its hands) led to a self-criticism session and “relegation” to the countryside.

In 1981, The Palace of Dreams, a chilling analysis of state-led paranoia, was withdrawn from sale and Kadare was not allowed to publish book-length novels thereafter. Yet throughout these tribulations – and occasional thoughts of emigration – Kadare’s output never flagged.

Kadare was one of the very few Albanians allowed to travel abroad. A visit to Turkey in the 70s brought him into brief contact with an American scholar of Balkan oral epics, Albert Lord: the result was a novel about the struggle for national identity through poetry, The File on H (1981). Kadare also visited China and he used some material from that trip for his Shakespearean fantasy of Maoist intrigue, The Concert (1988).

Foreign travel barely impinges on Kadare’s writing, which is almost always set in Albania, sometimes in disguise (as Egypt, in The Pyramid, for example, or Ottoman Turkey in The Palace of Dreams). But time travel is of the essence: Kadare’s novels range over the history of Albania from the invasion of the Turks in the 15th century (The Siege, 1970) to the monarchy of the 30s, the victory of the partisans, the communist reign (1944-92) and the post-communist period, while weaving into these stories myths from Greece and from the rich store of Balkan legends, together with echoes of Shakespeare and Dante.

Broken April (1978), perhaps the most read of Kadare’s novels in English, is a harrowing narrative of the blood feud as laid down in Albania’s ancient code of law, the kanun. Indirectly, though, it is an oblique assertion of the permanence of Albanian civilisation in the face of Hoxha’s attempt to replace it with the “new man” of Stalinist ideology.

Kadare’s recourse to national myths and legends – in The Ghost Rider (1979), for instance – resuscitates a national identity, and rejects attempts to suppress folk traditions, including religion. Kadare had little interest in contemporary literature; he was more at home with Aeschylus and Byron.

The fact that Kadare survived in an environment as hostile as that of Hoxha’s Albania led some in the west to accuse him of compromise. His appointment as a member of parliament, which he never attended, misled some into thinking him sympathetic to the regime. It is now accepted that these suspicions were unfounded. Kadare’s story is one of courage, persistence, wiliness and luck. The emergence of his work in a place as cruel as 20th-century Albania shows the resilience of the human soul.

Hoxha died in 1985 and was succeeded by Ramiz Alia, who maintained an isolationist and Stalinist regime. Kadare could not imagine that communism would collapse in his own lifetime, but he could see the weakening of the state and he feared the chaos it would bring. He fled to Paris in 1990 for personal safety, and also to give a signal to the Albanian regime. He was granted political asylum almost immediately and later awarded French nationality.

After the collapse of the Alia regime in 1991, Kadare divided his life between Paris, Tirana and a villa on the Albanian coast near Durrës.

In Paris, he used his influence to promote other Albanian poets and novelists, and wrote criticism and essays on his own approach to literature. Several volumes of interviews also appeared. Far from slowing down, Kadare’s rate of production remained intense throughout the 90s and the first two decades of the 21st century.

Even while he revised his entire opus in two languages for a bilingual complete works series for Fayard, published in parallel hard-bound volumes, he brought out new work in profusion.

Suppressed novels unpublished in their own time (Agamemnon’s Daughter, written in 1986 and revised in 2003), new novels portraying post-communist Albania through the same lenses of myth and dream (Spring Flowers, Spring Frost, 2000), and retrospective exploration of the mental torture of life under tyranny (The Successor, 2003), sequels to earlier novels (Fall of the City of Stone) and entirely new works such as The Doll (2020) continued to flow from Kadare’s pen through his 60s, 70s and 80s.

With each new work, the Kadarean universe acquired ever greater consistency and self-sufficiency. It adds up to a portrait not of the real Albania, but of an imaginary land – Kadaria, some have called it – with a single, central topic: how to remain human in a world ruled by fear and suspicion.

Kadare won a great number of literary prizes, among them the Man Booker international award in 2005, the Princess of Asturias award in 2009, the Jerusalem prize in 2015 and the Neustadt international prize for literature in 2020. Only the Nobel escaped him.

On a state visit to Albania last year, the French president, Emmanuel Macron, awarded Kadare the rank of Grand Officier in the Légion d’honneur.

Most of Kadare’s work is available in more than 40 languages, but several major novels and a swathe of short stories have yet to be published in English.

Kadare is survived by his wife, Elena (nee Gushi), herself a writer of distinction, whom he married in 1963, and two daughters.

• Ismail Kadare, writer, born 28 January 1936; died 1 July 2024