Squirrels gone wild in your L.A. yard? Here's how to get your revenge

Until recently I didn't think about L.A.'s squirrel population much. Now the tiny, bushy-tailed terrorists and the havoc they bring to my backyard consume my every waking moment. It started last summer when I hooked up a bird feeder capable of recording and notifying me of visits — kind of like a Ring doorbell camera for birds.

But the first visitor it recorded was dangling from its hind legs like a Squirrel du Soleil acrobat feasting on the bird seed.

At the time, I shrugged it off. After all, I reasoned, I'd altered the natural ecosystem, so what's the harm?

A year later, I can tell you exactly what the harm is: hundreds of dollars' worth of damage and repairs to my high-tech bird buffet and an unhealthy all-hours preoccupation with squirrel abatement. The three-squirrel gang has managed to dash the entire bird feeder to bits by chewing through the wire by which it was hung (once), chewing through the cord that connects the solar roof to the camera (three different times) and feasting so often and with such abandon that filling the feeder became a daily (instead of monthly) thing. To add insult to injury, each breach of the perimeter was brought to my attention immediately — no matter where I was — thanks to the app on my smartphone. It was like watching security camera footage of your own home being burgled.

After the third power-cord repair and 100th squirrel-at-the-feeder alert, most people probably would have thrown in the towel and capitulated to the crafty critters. I am not most people.

No, this squirrel insurgency would not stand. Not on my watch. I decided to wage an all-out war. And I would do it in as humane a way as possible (partly because I'm a softy, but mostly because my neighbor had named one Oscar and started feeding and treating him like a pet). But to do so, I first needed to learn what I was up against. That led me to the Natural History Museum's Southern California Squirrel Survey, which has been counting and cataloging the critters across the Southland for years and encouraging members of the community to do the same. The project results are tracked on a site called iNaturalist.

Read more: My high-tech bird feeder made me wonder: Do birds have a right to privacy?

Blame the government

According to environmental educator, wildlife biologist and co-lead of the project Miguel Ordeñana, the L.A. area is home to three species of tree squirrel (the western gray, the eastern gray and the eastern fox) and one species of ground squirrel (the California ground squirrel). He said that while the local population of squirrels overall has remained about the same over the last few years, the non-native eastern fox squirrel (Scirus niger) has been steadily expanding its habitat here since first being introduced from the other side of the country a little over a century ago.

Statistically, Ordeñana said, this was most likely the species living large in my backyard.

"It's well-documented in our museum records that one of the main ways the fox squirrel was brought into L.A. was through the Sawtelle Veterans Home," Ordeñana said. "A lot of the Civil War veterans came from the East by train and brought the fox squirrels with them."

Read more: When is it OK to pick someone else's fruit tree? We asked and sparked a tense debate

He added that the facility's staff wasn't exactly keen on keeping the rodents around. "They were like, 'Hey, this is [kind of] like a misappropriation of funds because they're basically using government housing and government food scraps. We need to get rid of them,'" he said. "It was also obviously unsanitary to keep squirrels in a hospital, so they got rid of them. And the community tolerated them for a while because they were new and charismatic, but they became a pest pretty quickly."

Ordeñana said the same thing that has helped the eastern fox squirrel take over the West Coast as it has also makes it a formidable backyard foe.

"The eastern fox squirrel is one of the most adaptable animals out there," he said. "Like a lot of generalist species, they can eat a lot of different things and have very plastic behaviors. They also reproduce a couple of times a year — compared to the western gray squirrel that only reproduces once [a year]. For all those reasons, it really sets the stage for this squirrel to take advantage and quickly become a pest. You'll try something like putting netting over your tomato plant, and it will figure out a way to lift it up or make a hole in it so you're basically back to square one. ... They're very dexterous and very acrobatic and will do whatever it takes to get to that food source."

Sight, sound and smell

Now that I knew what I was up against, it was time to launch Operation Ex-Squirrelfriend. My first break in the case came by happenstance when someone I was interviewing (on a totally different topic) mentioned that his wife was a wildlife rehabilitator with a soft spot for squirrelkind. In short order, I was emailing back and forth with Liz Grinspoon, who recommended a three-pronged approach.

"If wild mammals are in your home, we typically recommend using sight (bright light), sound (radio with music or people talking) and smell (tennis balls soaked in Pine-Sol or ammonia) to encourage them to leave," wrote Grinspoon, who lives in Massachusetts.

Even though I wasn't dealing with interior interlopers, Grinspoon's advice seemed humane and in keeping with what I'd already discovered in countless advice columns during my research. (It turns out that the only thing more common than backyard squirrels in L.A. are opinions on how to get rid of backyard squirrels in L.A.) In an effort to keep the peace with my neighbors, I decided to start with the smell prong and reassess as needed.

One case of tennis balls and one gallon of ammonia later, I no longer had a squirrel problem. I had a tennis ball problem and a squirrel problem. And I had a backyard that smelled like freshly cleaned windshields. (I filed away Grinspoon's suggestion — and that case of tennis balls — in case my outdoor squirrel problem ever becomes an indoor one.)

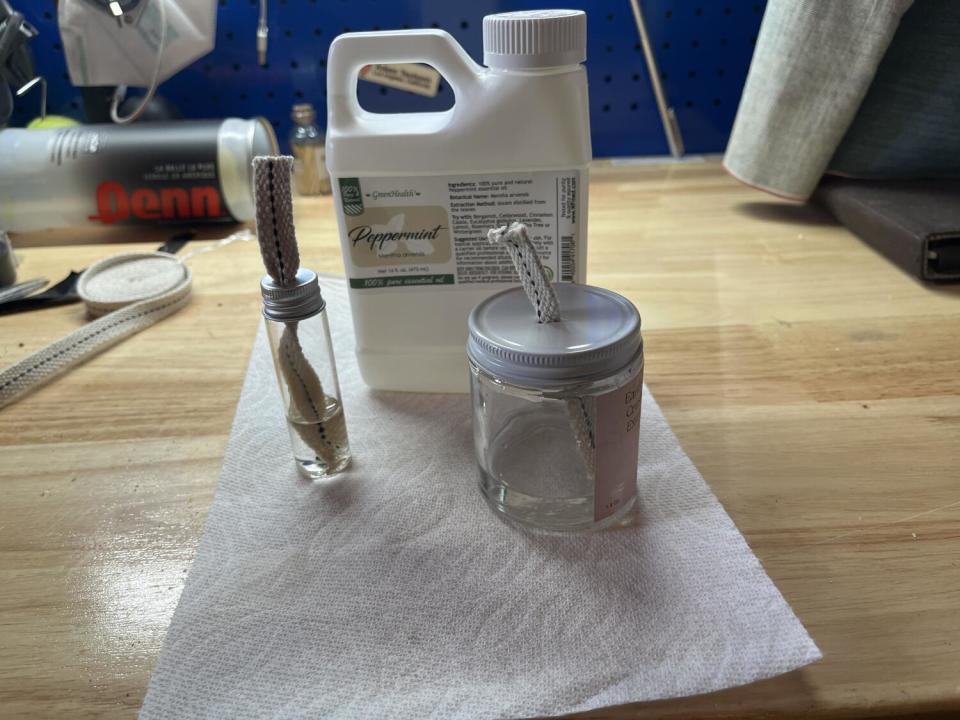

Next I cycled through every squirrel-averse scent I could dredge up online. Scattered coffee grounds? Nothing. Cinnamon? Nada. Chunks of Irish Spring soap tied up in a sock? Ineffective. (Not to mention creepy.) I was about to score some predator urine (it's a thing) when a friend, waging her own pitched battle to protect a backyard guava tree (from a squirrel she's dubbed Al Capone), mentioned that peppermint oil was a serious squirrel turnoff. Faster than you could say "candy cane," I was saturating every squirrel-trafficked inch of our backyard using a spray bottle filled with 100% peppermint essential oil.

Read more: Can this $24 device help you be more water-wise? We decided to find out

Almost instantly, Squirrel du Soleil became a deserted Squirrelnobyl. The bushy-tailed burglars were M.I.A. for four glorious, minty-fresh days. On Day 5, shortly after the backyard sprinklers stopped their cycle, a single squirrel tentatively zigzagged across the yard bound for the bird feeder. By Day 7, even with the backyard reeking like an industrial accident at a toothpaste factory, the tiny trio of terrorists was back in full force.

Physical barriers, professional counseling

This is the part where I admit two things — neither of which I'm proud of. First, it was only then, several months in, I realized I'd made a colossal blunder when trying to hang my precious high-tech feeder out of squirrels' reach. I'd measured the recommended five feet off the ground sure enough, but failed to account for the elevation afforded by a nearby tree stump that cut that distance in half. Within 10 minutes of realizing my error, I moved the feeder to a non-stump-adjacent location. Voila! My immediate problem was solved. As of this writing, it's been 40 days without a squirrel breach.

Second, even though I'd won the battle by accomplishing exactly what I'd set out to do, I refused to give up. I'd waged this war too long and invested too much. How could I sit back when my friend's guava tree continued to be routinely ransacked and my co-worker's avocados savaged and tossed to the ground with grubby-pawed abandon?

And worse yet, what if they decided to come for the single — and so far unscathed — orange tree just now starting to show pea-sized fruits in my backyard? No, I needed closure. But before I started investing in owl-shaped, light-up motion sensors (these exist) or blasting C-SPAN across my yard at all hours, I needed someone to tell me if protecting L.A. backyard fruit trees (humanely, remember?) was even possible.

And that's how I ended up on the phone explaining my situation to Roger Baldwin, a UC Davis Cooperative Extension specialist who focuses on human-wildlife conflict resolution.

Read more: How do you handle neighbors who smoke weed? And other burning weed questions answered

"You'll find various chemical repellents that are marketed and sold [to combat them]," Baldwin told me. "But there's nothing that's ever been proven effective against tree squirrels. So I wouldn't anticipate there being anything that you could spray to really keep them away. [And] there's no kind of sound devices or ultrasonic devices or lights or strobes — or anything like that — that's really been proven effective." (He did note that some repellents might work on a short-term basis until the wily critters adapt.)

"No," Baldwin said, "there's nothing that's guaranteed to work when you've got fruit trees, which are an abundant food source, and tree squirrels. ... But, like with your bird feeder, if you had an isolated tree — meaning nothing else around for a good 10 feet and nothing overhanging it — and its lowest branches were a good five or six feet off the ground, you could put a metal ring around the trunk to keep them from being able to climb it. But basically this is almost never going to happen."

He added that even trapping, which might be an option for those willing to consider the squirrel death penalty (in California, the eastern fox squirrel can be trapped and euthanized humanely — but not released elsewhere), would likely be only a temporary solution. "Invariably there's someone — probably more than one person — on your block feeding squirrels," he said. "And other squirrels will likely move in. And there's not much you can do about that. There are too many access points."

Read more: What are your secret tips and hacks for living in L.A.?

Sensing where things were headed, I cut to the chase. Based on Baldwin's 16 years of experience, did I have any viable options beyond accepting that my backyard would forever be shared with whatever eastern gray fox squirrels wished to have their run of it?

"There's probably not a lot that can be done to keep the squirrels from the fruit and the trees given the different limitations that you've discussed," he said. "Yes, it's more about realistically just learning to live with the squirrels."

Perhaps sensing my dismay, Baldwin offered a tiny glimmer of hope.

"Sometimes, if you've got a very aggressive dog in your backyard — one that can chase squirrels effectively — that can sometimes help reduce problems," he said.

Read more: 18 places in L.A. where your dog is more welcomed than you

We're a dogless household, and the notion of getting a dog just to vanquish a squirrel (or three) felt wrong. (I'm sure our two cats would agree.) So I'm accepting defeat on that front and keeping my focus on the no-longer-under-attack bird feeder.

But so help me, the minute one of those hairy little heathens helps itself to the fruit of my orange tree, the phrase "dogs of war" is going to take on a whole new meaning on my backyard battlefield.

Sign up for our L.A. Times Plants newsletter

At the start of each month, get a roundup of upcoming plant-related activities and events in Southern California, along with links to tips and articles you may have missed.

Sign me up.

This story originally appeared in Los Angeles Times.