Inside the Trust Women abortion clinic in Wichita, Kansas, which saw a spike in out-of-state patients after Roe was overturned

On a recent November day, I visited the Trust Women abortion clinic in Wichita, Kansas.

Post-Dobbs, the clinic says out-of-state patients now make up 81% of its visitors.

One patient traveled from Texas; another was turned away for being a week over the legal limit.

When I met Kattie in the waiting room of the Trust Women abortion clinic, she told me she already knew what it meant to be a parent. As the single mother to a 5-year-old, she'd been through the sleepless nights, long days, and frequent sacrifices that parenthood requires.

"So much just goes into parenting, you have to be mentally, emotionally, mentally, physically, spiritually there with that child," she said.

In October, when she discovered she was pregnant again, she thought about that strain and the stability she had fought hard to establish for her daughter. She worked 12-hour overnight shifts, sometimes every night of the week. Her decision was simple.

Putting it into action, however, was less so.

Kattie lives in Houston, Texas, where near-total abortion bans meant she couldn't get care. She called clinics in three states. One of them, which she thought would help her, ended up being a Christian group masquerading as a medical clinic.

Finally, she looked north and found Trust Women in Wichita, Kansas, where I first met her on a drizzly November day.

How Trust Women went from a catchphrase to a clinic

The clinic is bordered by a highway ramp on one side and a crisis pregnancy center on the other. Though the two are separated by a fence, a small sliver of the crisis pregnancy center was visible from the clinic's parking lot. Someone had hung a banner reading "Not sure about your abortion?" on it.

Outside, two protesters gathered with rosaries in hand, pacing in front of the entrance, as close as they were legally allowed. One of them told me she had been protesting there since the 1980s.

The modest beige building that houses Trust Women is no stranger to hostility. In 1986, the clinic that operated there at the time was firebombed. The explosion was so extreme that my father felt the rattle from his friend's home about a mile away.

Then, in 1993, Dr. George Tiller, its primary abortion provider, survived an assassination attempt that left him wounded in each arm by gunfire. In 2009 another attempt succeeded. Tiller was murdered while ushering at his church. (Many of the people who agreed to speak with me requested I use only their first name, citing safety risks or fearing harassment.)

Trust Women opened in 2009 in the wake of Tiller's assassination and established operations out of his clinic in 2013. Its name was the late physician's catchphrase, and it was also written on a memorial wreath at his funeral.

In response to this "hostile environment," abortion clinics across the country began using a rotating set of doctors instead of one who lives in the community, Zack Gingrich-Gaylord, the clinic's communications director, who was wearing a shirt that said "super pro abortion," told me. The practice is still common and has helped support newly overworked clinics.

Today, Trust Women is one of three clinics that offer abortions past 13 weeks in Kansas, and Gingrich-Gaylord says roughly 18 providers travel into the state once a month for two days to help support operations.

The clinic looks like any normal doctor's office, only with a bit more color. Stickers advocating reproductive rights pepper surfaces reserved for paperwork, pink feather boas line the doorways of the administrators' offices, and a picture of a halved papaya hangs in the waiting room.

Inside, I met a surgical technician named Carissa. She wore bright pink scrubs and had a tattoo on her arm of what looked like that same halved papaya. We talked in the intake room while she had a moment between assisting the doctor with procedures.

She described the increase in patients after the Supreme Court reversed Roe v. Wade in June 2022 as hectic, but she added that the clinic had since adjusted to the new workload. Now, each day felt relatively normal.

Earlier that day, I met the director of nursing, Kiernan, whose fine-line tattoos on her forearms depict plants traditionally used as birth control. As she sipped on her peppermint coffee in the intake room, she told me about her two-hour commute from Oklahoma City, and about the heartbreak she and other nurses felt when they were forced to stop providing abortion care in Oklahoma. "We should all be home," she told me.

The patients, meanwhile, wore an assortment of comfortable shoes — furry boots, Converse, and slippers. There was a minor accompanied by her guardian and adults on their own. The minor talked to her mother about a water bottle she had left behind at school. Another patient brightly told the older person she came with that her visit was "way quicker than I thought."

'Screw Texas'

Many of the conversations I had that day centered on the influx of out-of-state patients.

State after state across the country has enacted partial or total abortion bans since the Supreme Court struck down national abortion protection in its Dobbs v. Jackson Women's Health Organization ruling.

But Kansans voted to keep the procedure legal. That has meant clinics like Trust Women receive a large number of out-of-state travelers, especially from southern neighbors like Oklahoma and Texas.

After the Dobbs decision, the clinic's doctors, nurses, and administrators went from serving about 15 people a day twice a week to serving 50 people a day four times a week, Gingrich-Gaylord said. The clinic also fields 3,000 to 4,000 phone calls a day — a huge increase, Madison, the funding coordinator, told me.

"Now, there's not enough of us to even get the phones," she said. "Because they're just, they're constantly ringing. They never stop, ever."

This increase did not come from Kansans, according to Gingrich-Gaylord. For every 100 patients the clinic has treated since Roe v. Wade was struck down, he said, 81 have been from out of state.

The Guttmacher Institute estimates that abortions in the state increased 116% in the first half of 2023 compared with the first half of 2020. (The numbers in 2020 had been similar to those from 2019, even with the pandemic largely curtailing travel.)

In other words, the bans don't entirely stop residents from getting abortions — though they certainly make them a lot harder to get.

"I'm a Texas girl, born and raised off of hot-water cornbread and chicken. And I guess this is the first time when I say screw Texas, because you're not really giving us a choice," Kattie told me.

In the year since Roe v. Wade was overturned, Texas has seen the largest increase in births of any state that banned abortions. But nationwide, abortion numbers actually increased. This is partially explained by telemedicine making it easier to access abortion pills, and because there remain patients like Kattie who are willing and able to travel for an abortion.

Along with an increase in patients, increased national attention on Kansas has led to more investment from abortion funds, Madison said. Prior to Dobbs, the clinic had about $23,000 in annual funding — in 2023, it had $2.2 million, Madison added.

Even so, issues persist.

The clinic uses much of its funding to help out-of-state patients pay for travel and appointment fees. All told, travel costs for abortions can range in the thousands of dollars.

In many ways, Kattie was a typical visitor to Trust Women; Gingrich-Gaylord said more than half its patients, 54 in 100, travel from Texas. Wichita, about 600 miles away from Houston, is the closest option for many. But the drive from Houston to Wichita takes about nine hours, and Kattie couldn't take more than a day off of work.

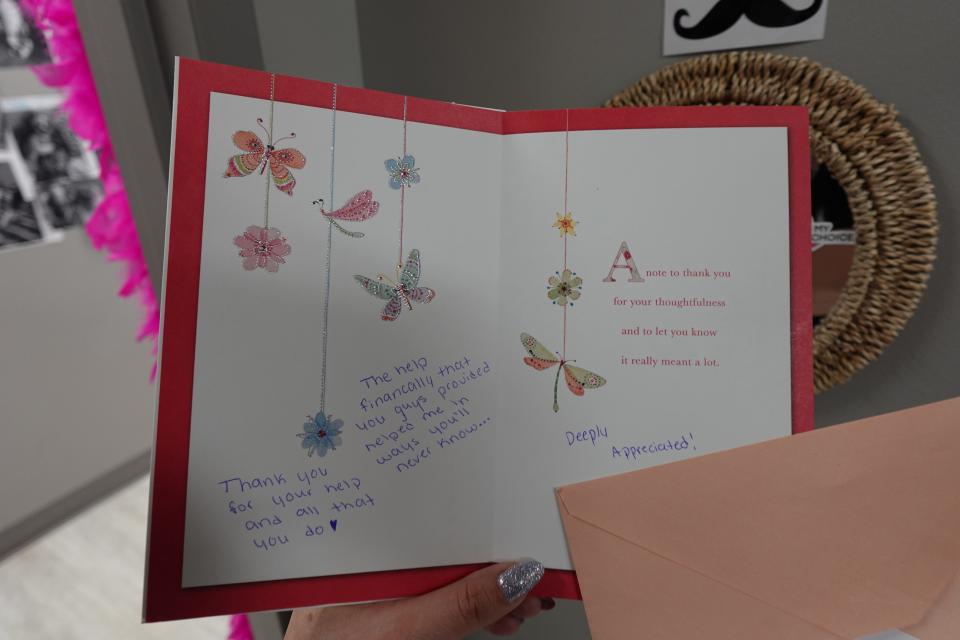

Flying, which also allowed her to return to her daughter that night, was her best option. The procedure was $750, and her plane ticket was $431. With funding from Trust Women for the costs of the procedure and from Planned Parenthood for the travel, she was able to cover it.

"I was just very grateful that they did help me out," she said.

Roadblock after roadblock

Kattie discovered she was pregnant when she was about five weeks along, on Halloween. By the time she found Trust Women, and by the time the clinic had a spot for her, four weeks had passed — still under the state's legal limit of 21 weeks and six days.

For others that day, the visit was much more fraught.

The "morning started with heartbreak," Stormi, Trust Women's assistant clinic director, told me as we talked in her office — in a separate wing from the clinic. They had to turn a patient away because her pregnancy was 23 weeks along — barely a week over the threshold.

In these cases, Trust Women sends the patient home with suggestions for clinics in other states, gift cards for gas, and other resources. But that feels like a Band-Aid for a bullet wound, Stormi said.

"The look on their face," she said, "and the sadness in their eyes and the fear that comes with it — it's what I hate about the job."

Kansas is one of 15 US states where abortion is only legal up to a very specific point during pregnancy. After 153 days of pregnancy, which is part way through the second trimester, Kansas doesn't allow women to get abortions. All other 35 states either ban abortion outright, allow abortion until fetal viability (around 23-24 weeks of pregnancy), or have no limit — meaning someone can get an abortion at any point during pregnancy.

Most people won't know exactly how far along they are until they visit a clinic for an ultrasound. They can get close by identifying the date of their last period, but that measurement isn't enough on its own to guarantee accuracy. By the time they manage to book an appointment, they may unknowingly have passed their state's legal limit — a particular challenge since the fall of Roe, because several bans that went into effect were based on gestational age.

Other difficulties are now on display in courts across the country.

For example, in December, Kate Cox sued her home state of Texas for permission to obtain an emergency abortion because she had pregnancy complications that were dangerous to her health and likely lethal for her fetus. She ultimately chose to seek out the procedure in another state; the Texas Supreme Court ended up ruling against her.

The same month, another woman in Kentucky pursued a similar charge. And Brittany Watts in Ohio was charged with felony abuse of a corpse for plunging her toilet after having a miscarriage into it. She has since been cleared of the charges.

Earlier, in a landmark lawsuit, 20 plaintiffs and two doctors asked Texas to clarify the state's definition of what makes an abortion medically necessary. They say the confusing nature of the law makes them afraid to intervene in a patient's care unless that patient is already thought to be dying. Anti-abortion laws are at their most powerful when they're difficult for doctors to interpret because they scare providers into inaction, Gingrich-Gaylord said.

If the language is unclear, doctors fear they might be prosecuted or lose their license for performing an abortion. "I don't think that we can underestimate the potency of a threat," Rachel O'Leary Carmona, the director of Women's March, a feminist activist group, told me.

Meanwhile, a looming Supreme Court decision on the safety of the abortion pill mifepristone could restrict abortion access even further. Data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention indicates more than half of all abortions in the US in 2021 were medication abortions. At Trust Women, about 40% of patients opt to use medication for their abortion, Gingrich-Gaylor said.

The legal murkiness trickles down to people seeking abortions. In Kattie's case, the confusion over where she was allowed to get an abortion unwittingly led her to a crisis pregnancy center.

The center advertised ultrasounds and reproductive healthcare, she said. But once it confirmed her pregnancy on ultrasound, it provided her with prenatal vitamins and a folder full of pregnancy resources.

She started sobbing at the news. The worker was judgmental of her response, she said, and told her that the center didn't provide abortions. Her treatment — compounded by the anguish of dealing with an unwanted pregnancy from an absent partner — left her distraught.

"I was just broken," she said.

Consequences that reverberate

The long-term consequences of a lack of care aren't theoretical. On the day I visited, Dr. Jennifer Kerns, who was rotating in from the University of California at San Francisco, found a few passing moments to talk as she sat in the intake room at the clinic. She brought up the Turnaway study.

The UCSF study followed about 1,000 women across the US who sought abortion care over five years. It compared the mental health, physical health, and socioeconomic status of the women who got abortions with those who carried their pregnancies to term after being denied medical care.

As the years went by, the study found that rates of depression, anxiety, and other mental illnesses were the same between the groups. But women who were denied an abortion were less likely to have full-time employment, more likely to require government assistance such as food stamps, and more likely to fall below the federal poverty level.

The group that was turned away also had worse health outcomes, which is to be expected, the study authors explained: Giving birth is more dangerous than an abortion.

Kerns predicts this will probably become increasingly apparent in states with abortion restrictions. It's still early, but a KFF poll of 569 OB-GYNs across the US conducted from March to May found that 64% of respondents said that the Dobbs decision had worsened pregnancy-related mortality.

In the face of bans

Still, O'Leary Carmona noted that voters have widely opted to protect abortion rights when the issue has appeared on the ballot. "It's very clear from polling, it's clear from electoral outcomes, that most Americans do not favor abortion bans," she said. As many as nine states are expected to put the issue to voters in 2024.

In the meantime, Trust Women is prepared for "a long fight ahead," Gingrich-Gaylord said.

Leaving the clinic that day, that fighting spirit was clear to me. The workers there drove long distances each week to staff the clinic, endured stalking and death threats, and constantly feared losing the ability to care for their patients. Yet they were kind, funny, and passionate.

The patients, in the face of similar obstacles, were resilient. It's heartening that at the end of the jagged journey many had to face, Trust Women was a soft spot for them to land.

Kattie, meanwhile, made it back to Houston the same day that she got her procedure. She told me the travel home was easy, and the recuperation was relatively seamless. She had been nauseous and sick, unable to eat, for almost every day of her pregnancy. So the recovery was easy by comparison.

In the days after, she felt a little emotional but kept coming back to the same conclusion that led her to Trust Women in the first place.

"Making this conscious decision, I'm standing firm on it," Kattie said. "Because, you know, at the end of the day, when your baby is sick, and you still have to go to work, and you're up all night, those people that talked about you are asleep."

Read the original article on Business Insider