Inside the 470-year-old stately home designed to impress Queen Elizabeth I

The history and beauty of Burghley House

![<p>Unknown artist / Wikimedia Commons [Public domain] ; wayne midgley / Shutterstock</p>](https://s.yimg.com/ny/api/res/1.2/LgHrOUad1EpGuiag_pSb_Q--/YXBwaWQ9aGlnaGxhbmRlcjt3PTk2MDtoPTYxOQ--/https://media.zenfs.com/en/loveproperty_uk_165/9531113be6eaf37e5acf67a475472a26)

Unknown artist / Wikimedia Commons [Public domain] ; wayne midgley / Shutterstock

Possibly one of the most impressive stately homes in the whole of England, this sprawling 470-year-old estate near Stamford in Lincolnshire was originally built to honour Queen Elizabeth I.

Built between 1555 and 1587, Burghley House is a Grade I-listed historical landmark containing more than 100 rooms but what stories lie behind its stately walls? Read on to find out...

Who built Burghley House?

The History Collection / Alamy Stock Photo

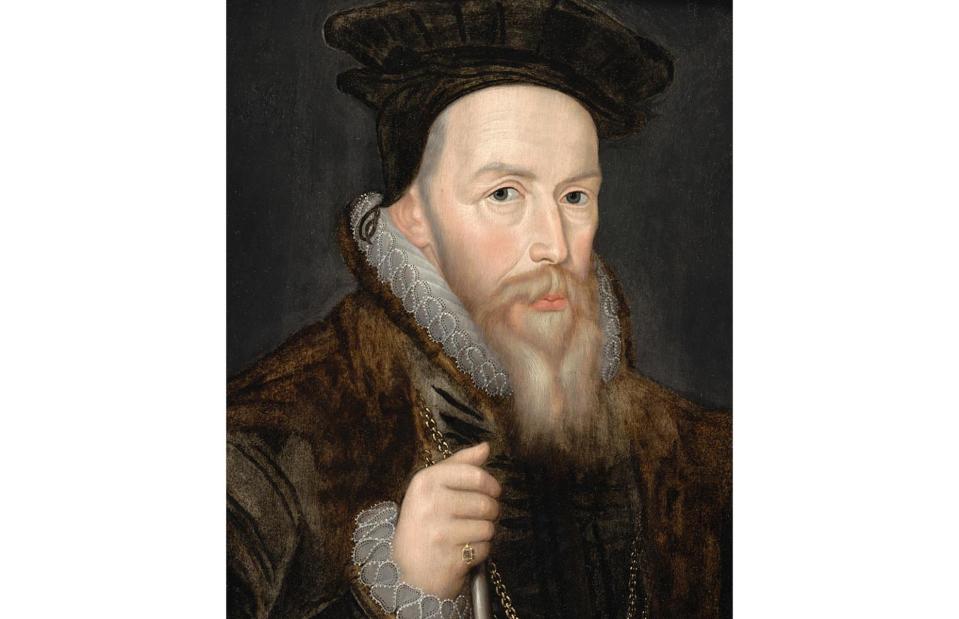

Burghley House was commissioned by William Cecil, the first Baron Burghley, one of the most powerful and influential advisors in Queen Elizabeth I’s privy council. William was knighted in 1572 and went on to serve as secretary, Lord Treasurer and Chief Minister to Elizabeth, with whom he built a close personal relationship.

In return, Elizabeth rewarded the newly minted Lord Burghley with vast land grants. Burghley House was already a substantial residence in 1571 and Cecil hadn't held back on spending his money on its decoration and maintenance. But after Elizabeth showed him favour, he dedicated the next 30 years of his life to fashioning it into his dynastic family seat in her honour.

Where is Burghley House?

Greg Balfour Evans / Alamy Stock Photo

To this day, Burghley remains a family home, owned and operated by a direct descendant of Lord Burghley, though it is open to the public for much of the year. It's near Stamford, a 'stone town' (an area with a long history of stone quarrying), so the stone used for that impressive facade came from nearby town Kingscliffe.

The home's frontage features a symmetrical arrangement of towers and turrets flanking a central gateway, reflecting English castle architecture from the late 13th century. Within a gatehouse entrance, built in 1801 (pictured) a vaulted ceiling is decorated with heraldry of the Cecil family, with one shield holding a Latin inscription that reads ‘William Lord of Burghley 1577’. It's all very grand indeed.

A real 'prodigy'

David Peter Robinson / Shutterstock

Although it looks like a castle, the estate is technically classed as a 'prodigy house'. This is a term used to describe the opulent country houses built by courtiers during the Elizabethan period for the purposes of showing off the status of their owner, as well as the aim of hosting the monarch herself.

Cecil dominated Elizabethan politics, with detailed knowledge of political movements across the country. It is said that 'nobility meant the world to him' and he longed for Queen Elizabeth to know how much he appreciated his place in her court.

The Queen's royal tours

Pictorial Press Ltd / Alamy Stock Photo

One of Elizabeth I’s most noted strategies as a monarch was her regular ‘royal progresses', essentially tours of the provinces. During these travels, she and her entourage would make extended visits to the various stately homes of favoured members of her court.

It was meant to make the queen appear to be an accessible, tangible figure to her subjects, as well as being acts of political favour bestowed upon the courtiers whose homes she deigned to visit. Cecil was therefore hopeful that she would come to Burghley, showing everyone how important he was in her eyes. But this never came to pass...

One of three incredible homes

Louise Heusinkveld / Alamy Stock Photo

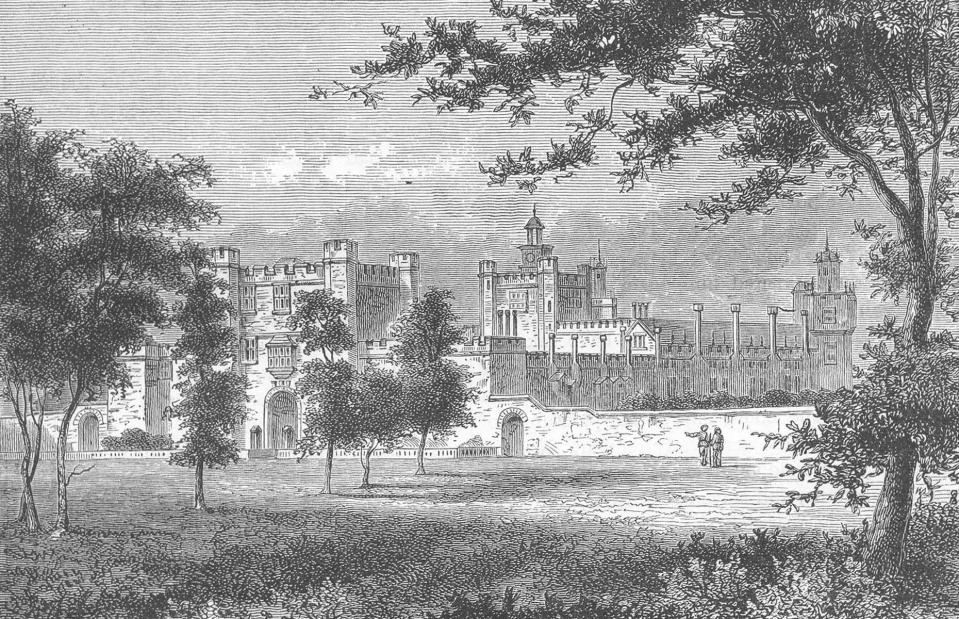

During his life Cecil owned at least three houses, using them to demonstrate his status, wealth and power: Theobalds in Hertfordshire, Cecil House on the Strand in Westminster and Burghley (pictured), which was essentially his office and where he hoped Elizabeth would visit him.

While prodigy homes like Burghley varied in architectural style, they were largely renaissance-inspired with an emphasis on symmetry and scale, and have been described by architectural historian Sir John Summerson, who coined the term, as “the most daring of all English buildings." Cecil certainly spent a daring amount of money on his properties, changing details of them on the whim of his beloved queen...

Theobalds Palace

Antiqua Print Gallery / Alamy Stock Photo

For an example of Cecil's eagerness to impress Queen Elizabeth I, we must quickly divert from Burghley and visit his other home of Theobalds (pronounced Tibalds and pictured here in around 1836). Cecil acquired the manor in 1564 and had a house built, which soon received a visit from Elizabeth. She was impressed by the house and its surroundings but during a stay, according to reports, complained that her bedroom was too small.

Of course, this led Cecil to embark on a huge programme of building work. "Upon fault found with the small measure of her chamber (which was in good measure for me), I was forced to enlarge a room for a larger chamber," he wrote in his diaries.

E for Elizabeth

donnadesign / Shutterstock

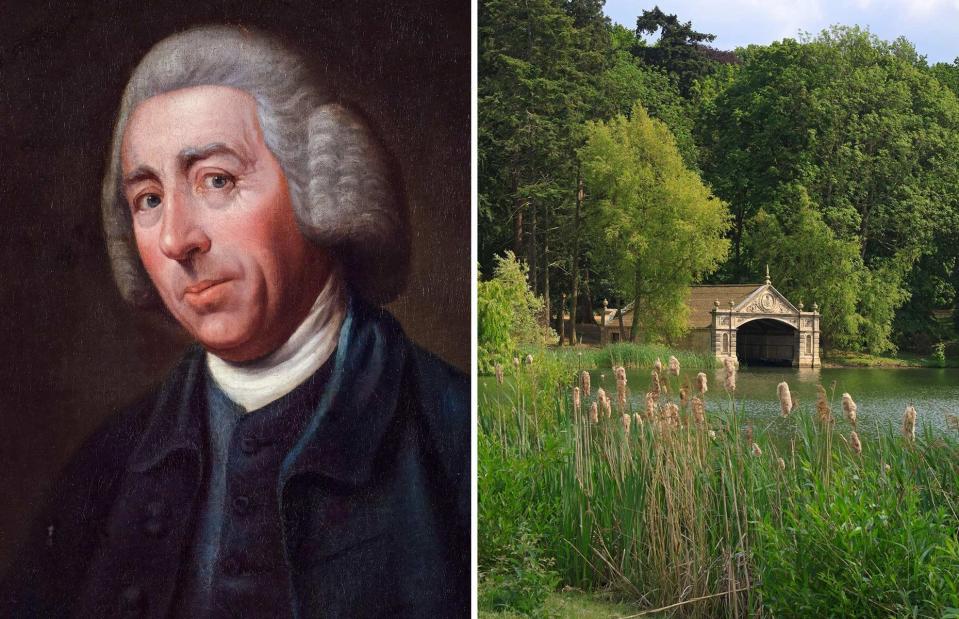

Cecil was so keen to thank Elizabeth for her favour that the original floorplan for Burghley house was in the shape of an ‘E’ in honour of the queen. But during its ownership by the 9th Earl, under the advisement of famous landscape architect Capability Brown, the northwest wing was demolished to allow for better views of the surrounding parklands.

So, the most important question lies unanswered. After all this effort on Cecil's part, did Queen Elizabeth I make it to Burghley House? And what did she make of it?

The thwarted royal visit

ronald ian smiles / Shutterstock

In an ironic twist of fate, Elizabeth never managed to visit the completed Burghley House. According to some reports, her one planned visit was called off at the last minute because William Cecil’s daughter had smallpox, other records say it had spread to the staff too.

Nevertheless, Cecil was still a valued member of The Queen's court, he was known as her 'spy-master' keeping an eye on potential trouble-makers. He died in 1598, having never hosted Elizabeth at Burghley House. However, even if Elizabeth did not make it inside, we can still take a tour...

Designed to impress

parkerphotography / Alamy Stock Photo

Even in its current, slightly reduced state, the house boasts 35 elegant state rooms across the ground and first floors, plus over 80 smaller rooms, bathrooms, corridors, staircases and service areas. Impressive decor is everywhere you look.

Though he corresponded with prominent Dutch architect Hans Vredeman de Vries seeking advice on the design, Cecil created the layout for the house himself, as was traditional with most prodigy houses.

Tudor elements

trabantos / Shutterstock

The home’s exterior is largely unchanged from its original 16th-century construction, but the majority of its interiors are the result of an extensive remodel in the 1800s.

However, many Tudor architectural elements have been preserved throughout the home, such as the ornately carved stone fireplace visible here in the main hall, and the wooden panelling and sconcing which adorn the double-height walls and ceiling.

A busy Tudor kitchen

trabantos / Shutterstock

Part fairytale castle, part treasure trove, this great building has been repeatedly reworked but there are classic ‘Tudor’ design elements in almost every room. The palatial kitchen, seen here, looks equipped to prepare any state banquet, though today it is more a museum piece to show off over 250 copper pans.

However, with its lofty ceilings of over 30 feet, cavernous ovens and a wealth of cookware, it’s not hard to imagine the bustling culinary epicentre the space would once have been. Through the kitchen is the ‘Hog’s Hall’ which holds the bells to summon the servants to various rooms in the home.

European influence

trabantos / Shutterstock

While very much an English home, between 1648 and 1700, the estate came under the ownership of the 5th Earl of Exeter, John Cecil, who, along with his wife, Anne Cavendish, set about transforming the estate into their vision of a European palace.

As great art collectors, the couple travelled the continent extensively resulting in the nickname 'the travelling Earl' for John. They met with prominent French and Italian artists of the time and commissioned some of Europe’s most skilful craftsmen to renovate Burghley House.

Heaven and hell murals

miscellany / Alamy Stock Photo

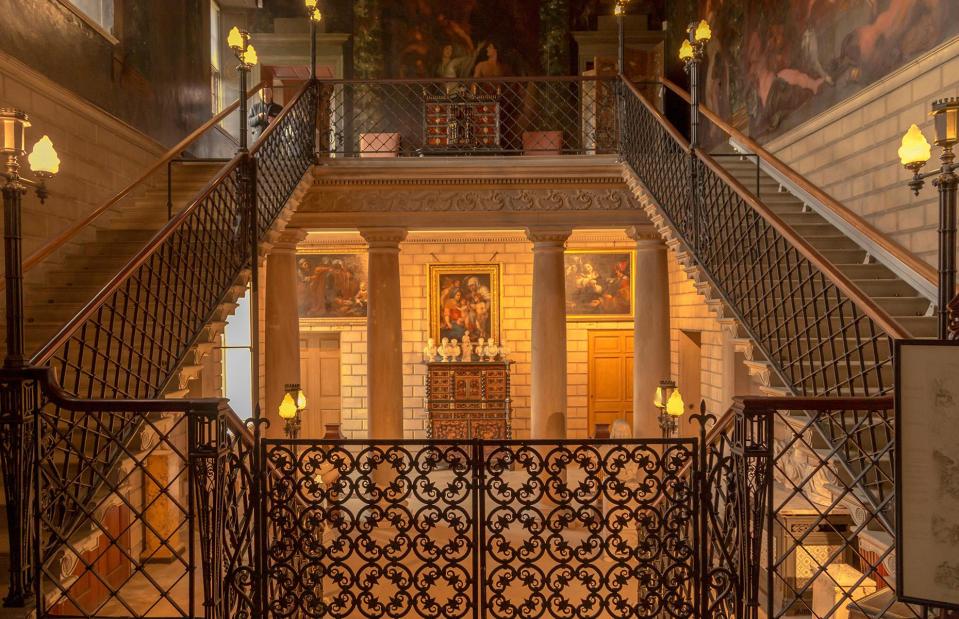

Arguably the most significant contribution commissioned by the couple were the two murals which completely cover the walls and ceilings of the ‘Heaven Room’ (pictured here) and the ‘Hell Staircase’, named, rather dramatically for the classical scenes they show.

The murals were painted by famous Italian Baroque artist Antonio Verrio in the 1690s, and are one of the most famous attractions in the estate. And you cannot really miss them due to their size anyway!

The George Rooms

trabantos / Shutterstock

This bold space is down to another of Cecil's descendant's influence. In 1754, the title was inherited by Brownlow, the 9th Earl of Exeter, an enthusiastic collector and patron of the arts. It was under Brownlow that the 35 state rooms, known as the George Rooms, were finally finished after nearly 50 years of remaining untouched.

The rooms were mostly redecorated in a traditional Baroque style, becoming galleries for the palace’s spectacular art collection, curated over four centuries’ worth of acquisition.

Enter Capability Brown

Art Collection 3 / Alamy Stock Photo ; Louise Heusinkveld / Alamy Stock Photo

It was also the 9th Earl who commissioned Lancelot 'Capability' Brown to design the surrounding parkland and gardens in the popular ‘naturalistic’ style. He was paid a total of £23,000 ($28.9k) for his work on the park, a staggering sum equivalent to £3.4 million ($4.3m) in today’s money. Burghley is home to one of only two portraits of Capability Brown, on display in the state rooms, so you can put a face to the famous name if you visit.

Brown's Arcadian paradise

Hellwing71 / Shutterstock

Brown was known for his sweeping Arcadian views and avenues of mature trees, evoking an idealised 'English' landscape dotted with decorative follies and buildings. He created the park’s man-made lake, its famous Lion Bridge (pictured here), extensive stables, an orangery and a gothic-style summer house for the grounds and reportedly described the work as “twenty-five years [of] pleasure in restoring the monument of a great minister to a great Queen”.

The parklands today

Gardens by Design / Shutterstock

Left to the Burghley House Preservation Trust by the 6th Marquess of Exeter in 1987, the estate today is comprised of extensive farmland, woodland and a substantial property portfolio, much of which is available to let.

The parkland has been preserved to honour Brown’s original design and is open year-round to visitors and the local community, as well as home to vast herds of deer and sheep. There is also a sculpture garden, a collection of water features and

Victorian interiors

trabantos / Shutterstock

Moving back inside, the home’s interiors date predominantly to the 19th century and can mostly be attributed to Brownlow, the 2nd Marquess of Exeter, who took over the estate in 1816.

The 2nd Marquess took great pains to update Burghley’s interior design for modern living and to make it suitable for hosting royalty. This time the house was successful! Most notably in 1844 when it got a visit from Queen Victoria and Prince Albert no less.

Significant collections

trabantos / Shutterstock

However, Brownlow’s expensive tastes extended beyond interior design, and he seriously depleted the family fortune through his love of horse racing, resulting in the forced sale of many treasures from the ancestral collection.

In spite of these losses, as well as several others incurred through death duties (a form of inheritance tax in the UK), the collections remain one of the most impressive in the country. Burghley is brimming with hundreds of paintings, a large collection of Japanese export porcelain, ceramics, silver and articles of furniture.

Curation and accessibility

trabantos / Shutterstock

There is also an interactive online database which catalogues the complete collection, allowing scholars and art history enthusiasts alike to browse the carefully curated assortment of Italian Old Master paintings, English and Continental furniture and 17th-century Objects of Vertu at their leisure.

We're especially taken with the 'objects of vertu', smaller pieces designed to be beautiful as well as functional, created from precious materials and intended to be admired simply as works of art or, more often, as luxury items with a practical purpose. Think ornate trinket boxes and decorative photo frames...

Wartime recovery

![<p>Derek Voller / Wikimedia Commons [CC BY-SA 2.0]</p>](https://s.yimg.com/ny/api/res/1.2/os33_6PobxIsQdMheSYCgw--/YXBwaWQ9aGlnaGxhbmRlcjt3PTk2MDtoPTYxOQ--/https://media.zenfs.com/en/loveproperty_uk_165/d340c940fc51a05b9938fc254bbb330e)

Derek Voller / Wikimedia Commons [CC BY-SA 2.0]

As with most country houses, the First and Second World Wars brought a host of difficulties for Burghley House, which served as a hospital for wounded soldiers during both conflicts.

However, it was one of the first major houses to reopen in 1946, bolstered by a strongly worded letter from the 5th Marchioness demanding tax relief and increased support for maintenance to prevent the dispersal of the home’s historic collections.

The home of the Burghley Horse Trials

Land Rover Burghley / Getty Image

Brownlow was not the only Marquess with a penchant for equestrian sport and a desire to see Burghley House remain in public favour. In 1956, the title and home were inherited by David Cecil, a distinguished athlete and Olympian whose accomplishments were immortalised in the film Chariots of Fire.

Cecil undertook a series of substantial modernisation and maintenance projects on the estate, including the introduction of electricity. As the proprietor of Burghley, he channelled his love of sport into horse riding, introducing the annual Burghley Horse Trials, which are still held today.

A massive restoration project

![<p>Derek Voller / Wikimedia Commons [CC BY-SA 2.0]</p>](https://s.yimg.com/ny/api/res/1.2/a2bhMxZnIxkxTMr4hBwDvA--/YXBwaWQ9aGlnaGxhbmRlcjt3PTk2MDtoPTYxOQ--/https://media.zenfs.com/en/loveproperty_uk_165/11747e69ea0a2028024ef6b512cb273f)

Derek Voller / Wikimedia Commons [CC BY-SA 2.0]

In her 1992 work, Burghley: The Life of a Great House, Lady Victoria Leatham, David Cecil's daughter, recalled her childhood memories of the home in desperate need of restoration: “Nobody had decorated much since World War I… Furniture was displayed in the most extraordinary way and everything needed repair. The many pictures that my grandfather had enthusiastically coated with poppyseed varnish were now black and shiny.”

David Cecil, the 6th Marquess, died in 1981. It was his dying wish that a member of the family always remain in residence at the estate and that they serve as director of a family trust he established in 1969.

A family legacy

Steffie Shields / Alamy Stock Photo

This wish was granted as Lady Leatham has lived at Burghley since 1982, looking after the house on behalf of the family-run Burghley Preservation Trust, an organisation dedicated to conserving the estate as a historical resource for future generations.

In 2007 she passed her responsibilities on to her daughter, Mrs Miranda Rock and the house has been continuously maintained and used for several interesting projects...

A popular filming location

Mieneke Andeweg-van Rijn / Alamy Stock Photo

With its impressive facade and atmospheric state rooms, it is no surprise that Burghley House is a coveted backdrop for period films. Indeed, the estate’s cinematic connections extend well beyond Chariots of Fire.

In recent years it has been used as a filming location for numerous projects, including Middlemarch, the 2005 adaptation of Pride & Prejudice, The Da Vinci Code, The Crown, Top Gear and most recently The Flash, among many others.

Burghley House in the 21st century

Steven Booth / Alamy Stock Photo

Part fairytale castle part treasure house, this great building, with its Tudor beginnings and constant revival ever since, continues to attract visitors from around the world.

In fact, annual visitor numbers had nearly doubled to reach more than 110,000, before the arrival of lockdown according to Country Life, with Mrs Rock appreciating how special Burghley House truly is: "Even now, each time I drive into the park, I am amazed that we live here — it is such a romantic and magical house." We couldn't agree more.