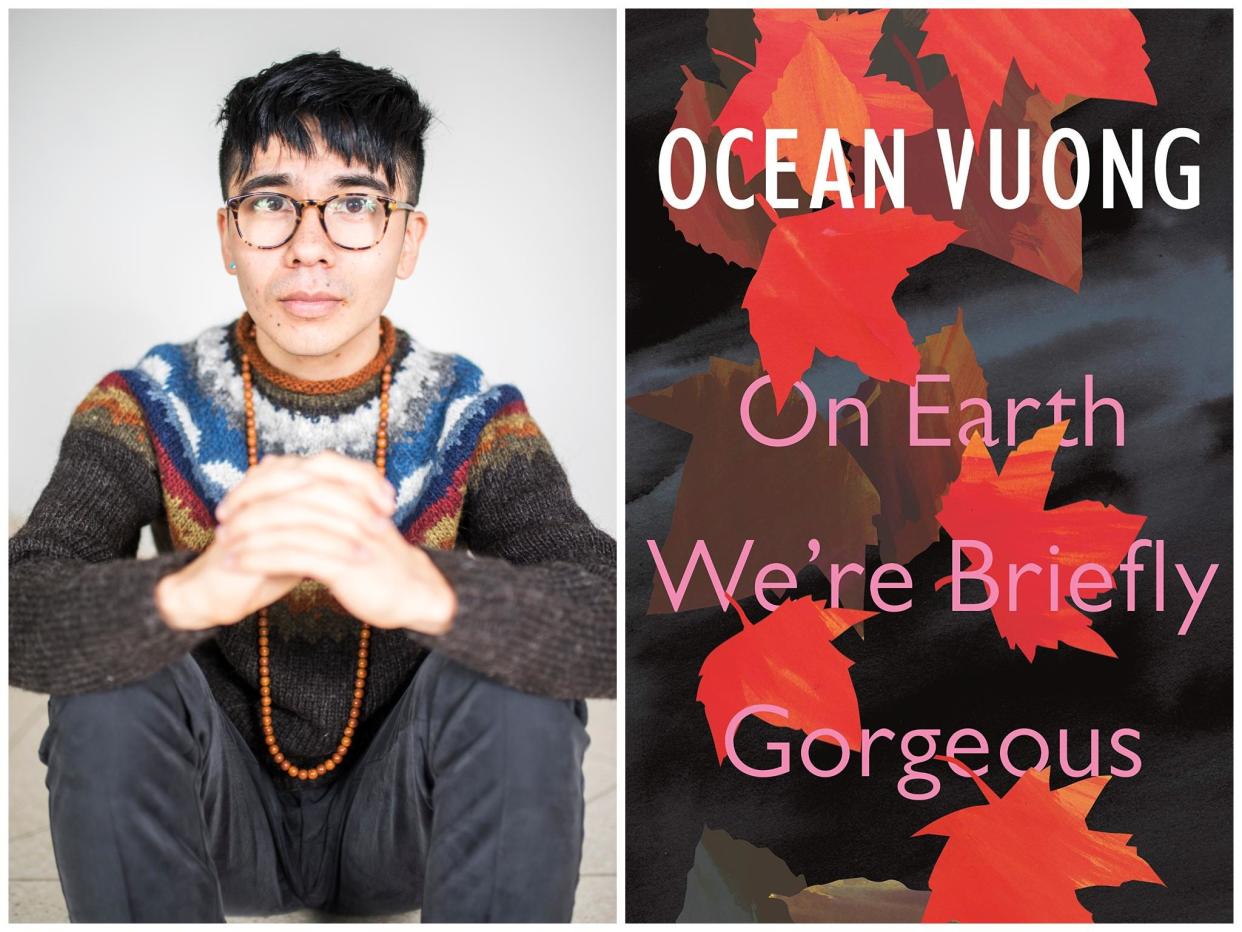

The Indy Book Club: On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous shows how often love is tied to pain

On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous, the debut novel by TS Eliot Prize-winning poet Ocean Vuong, is a love letter from Vietnamese-American son “Little Dog” to his mum Rose, whose illiteracy means she will never read it. Sitting in the murkiness between fiction and memoir, On Earth... sees Little Dog telling Rose their story. How she was conceived in a brothel by a soon-to-disappear American soldier during the Vietnam War. How she married a man who beat her until her skin turned purple. How the family fled a refugee camp, when Little Dog was a toddler, to Hartford, Connecticut to find a better life. How that “better life” meant Rose working in a nail salon with chemicals so strong her hands resemble “two partially scaled fish” and later at a clock factory where after long shifts sweating over metal parts, she passes out in the bath, leaving Little Dog “afraid she would drown”.

Essentially plotless, Vuong’s deeply tender prose loops around in different time zones and perspectives, most often that of Little Dog growing up in the Nineties, but also his journey into adulthood and literary acclaim in the 2000s, and also back to Lan, his Grandma, in Vietnam in the Seventies. At points, there are long, essayistic meditations on anything from Tiger Woods’ Asian heritage to America’s opioid crisis. In the final part of the book, Vuong jettisons the prose for poetic verse, with Roland Barthes, Duchamp’s Fountain and queer love all collapsing into splintering lines of verse. Vuong’s sentences are so beautiful, sometimes I would say them over and over again in my head, hoping I might be able to trap them in there.

For Little Dog, love and pain are indistinguishable. It’s almost impossible to tease the two feelings apart. Little Dog’s humiliating name comes from the Vietnamese tradition of referring to a child as something so worthless, evil spirits will spare them from torture. Rose loves her son, but she acts as though she hates him in order to toughen him up for life in a country that often doesn’t want him. After boys on the school bus beat up Little Dog, Rose slaps him harder than they did. “You have to step up or they’ll keep going,” she tells him, getting so close to his face that he can smell the ash and toothpaste between her teeth. “You have a bellyful of English,” she says, her palm on his stomach now, “you have to use it”. From then on, she forces him to drink milk every day, pouring a “thick white braid” of it into his glass to make his bones stronger than the bullies’. In an earlier passage, Vuong wonders: “Perhaps to lay hands on your child is to prepare him for war.”

When he’s 14, Little Dog starts working at a tobacco farm. It’s there that a blonde-haired, blue-eyed boy says, “I’m Trevor,” from the shadow of a metal army helmet. American as apple pie, Trevor smells like peanut butter and his mouth tastes like french fries. He knows all the words to 50 Cent’s “Many Men (Wish Death)”. There’s motor oil under his fingernails and he has a Fentanyl addiction that will eventually kill him. When they touch for the first time in the hay barn, with a Patriots game humming on the radio, Little Dog repeats the submission he performed earlier under Rose’s fists. “Violence was already mundane to me, was what I knew, ultimately, of love,” says Little Dog. Now he is “being f***ed up, at last, by choice”.

Through Trevor, a little lightness comes to the novel, as Little Dog sees his own body as beautiful just for the way it looks in his lover’s eyes. In one scene, he considers his ribs in the reflection of a mirror, “sunken as the skin tried to fill its irregular gaps”, and the “sad little heart rippling underneath like a sad fish”, and for a short moment in these flaws, hurt gives way to healing. “For once” begins Little Dog, “they were not wrong to me but something that was wanted, that was sought and found among a landscape as enormous as the one I had been lost in all this time.” One day, boys like Little Dog might be able to feel love without feeling pain first. A mother might not have to prepare her son for war, but for joy. Or, to borrow a phrase from one of Vuong’s poems, you might not have to break kneecaps just to show the sky.

And here’s what some of our readers thought...

Steven, 41, London

I found the poetic language exhausting. I would have rather Ocean Vuong just said what he wanted to say clearer and then I think I would have been more emotionally touched by the book. Some of the phrases I just thought too easy and didn’t really do it for me. “Our facts lit us up and our acts pinned us down” is one example.

Neesha, 22, Manchester

I’ve never read something that’s so clearly expressed the messy, nervous exploration involved in teenage sex. Because so many gay love stories end in tragedy, reading the book I was so convinced Trevor was going to hurt Little Dog, maybe even kill him. There is a sad end, but I was glad it wasn’t one that was a punishment for being gay.

Hannah, 23, London

I didn’t like the way it broke down into poetry at the end. I thought the story should have focused more on Trevor and Little Dog and in following the tangents of Tiger Woods and art and all that, the story became a bit lost. For me the prose was, perhaps, too beautiful, too resonant, without enough plot.

Mandy, 43, Hull

I was confused constantly where I was in Little Dog’s life and the narrative. But it never bothered me because of the strength of Vuong’s writing. He didn’t write the book, he sliced himself open and bled onto the page. Reading it cut me too, and turned me inside out. Just a sample: “Did you know people get rich off of sadness? I want to meet the millionaire of American sadness. I want to look him in the eye, shake his hand, and say, ‘It’s been an honour to serve my country.’”

Our next Indy Book Club choice is Convenience Store Woman by Sayaka Murata. Send your thoughts on the book to annie.lord@independent.co.uk