Incredible prehistoric discoveries uncovered recently

Messages from the past

Greek Ministry of Culture

Before life as we know it began, early humans walked the Earth at the same time as woolly mammoths and sabre-toothed tigers. Through several prehistoric eras they lived, hunted and evolved, leaving traces of their primitive presence that are still being unearthed today. In the last four years, experts have found tombs, footprints, rock carvings and the remnants of Europe's oldest village from the Ice Age, Stone Age, Copper Age, Bronze Age and Iron Age.

Read on as we reveal the recent prehistoric discoveries that have amazed archaeologists...

Iron Age warrior woman, England, UK

Historic England Archive

In the Iron Age it was typical for men to be buried with weapons and women to be buried with mirrors. So when a 2,000-year-old burial pit containing only one body but both items was found on Bryher, in the Isles of Scilly, more than 20 years ago, it left archaeologists baffled. That was until July 2023, when new DNA analysis of the heavily degraded skeleton’s tooth enamel proved with 96% certainty that the figure was a woman. The findings break new ground by suggesting that women actively participated in Iron Age warfare.

Bronze Age tombs, Cyprus

PM Fischer/University of Gothenburg

Laden with riches and rare gems, a series of Bronze Age burial chambers was discovered in southern Cyprus in early 2023 by a team from Sweden’s University of Gothenburg. Unearthed near the important copper-trading city of Dromolaxia Vizatzia, the graves contained more than 500 treasures, including gold and ivory from Egypt, semi-precious stones from Afghanistan, India and the Baltic, and bronze weapons. This makes the tombs some of the richest ever found in the Mediterranean – perhaps belonging to minor royals or wealthy government officials.

Stone Age shrine, the Netherlands

Municipality of Tiel

Dubbed 'the Stonehenge of the Netherlands', this ceremonial site dates back around 4,000 years and was in use for eight centuries, spanning the end of the Stone Age and the dawn of the Bronze Age. Like the British stone circle it's been compared to, the shrine was designed to align with the sun on the summer and winter solstices. The discovery is notable for its size – equivalent to three football pitches – which encompasses the burial sites of around 60 people. Unearthed by construction workers in the town of Tiel, the site was first excavated back in 2017 but is only now being fully understood.

North America’s oldest human footprints, New Mexico, USA

Courtesy of the National Park Service

Humans roamed what is now North America between 21,000 and 23,000 years ago – that's what was proven by the recent discovery of ancient footprints at White Sands National Park in New Mexico. First found in 2019, in September 2021 it was revealed the footprints were made at least five millennia before it was previously thought humans had arrived on the continent. The tracks were embedded in the bottom of Lake Otero, which dried up some 10,000 years ago, and are so well-preserved they look like they could have been made yesterday.

High-status Iron Age burial pits, Austria

© NHM Wien, Andreas W. Rausch

Not just a pretty face, the famously photogenic Alpine town of Hallstatt is also a hotbed of prehistoric relics. Its latest discovery is a previously untouched, high-status cremation grave found within an Iron Age cemetery, replete with bronze offerings. The grave was seemingly missed by major excavations carried out in 1843, which revealed over 1,000 burials. This burial is different for another reason – researchers say the remains were probably placed in a cloth bag, revealing a new practice in the Iron Age Hallstatt culture.

Early evidence of human drug use, Spain

Consell Insular de Menorca

The earliest known evidence of drug-taking in Europe was unearthed in a Menorcan cave in 2023, dating back to the first millennium BC. The new research, published in Scientific Reports, suggests that people once living in the Es Carritx cave on the south side of the island used plant derivatives as DIY narcotics to achieve highs and hallucinations. Scientists studying hair samples from the cave’s human remains found traces of three psychoactive substances, which can all be found in vegetation native to Menorca. Some scholars believe psychedelics could have played a role in the rituals of our prehistoric ancestors.

Bronze Age petroglyphs, Sweden

Foundation for Documentation of Bohuslan’s Rock Carvings

The coastal province of Bohuslan in western Sweden is known for its petroglyphs (artworks made by carving or chipping into rock), and now it has even more to add to its collection. Forty new images, estimated to be 2,700 years old, have been found under a thick carpet of moss on a sheer rock face. The rock face was once the edge of an island, so whoever made the carvings must have been in a boat or on a platform. Maritime life was obviously a source of inspiration for the artist, as one of the biggest newfound glyphs depicts a 13-foot-long (4m) ship.

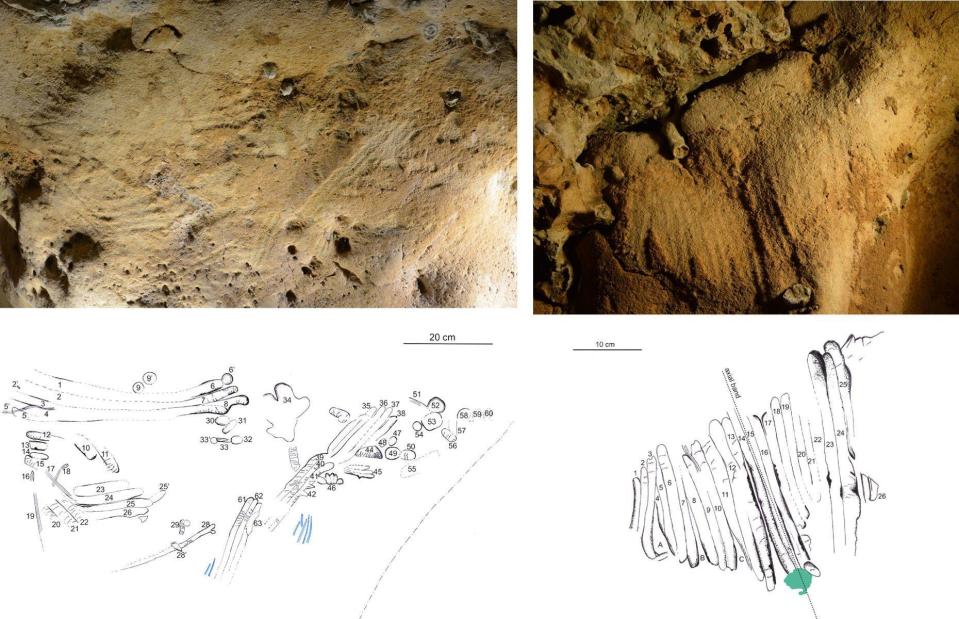

Europe’s oldest known intentional cave engravings, France

O. Spaey and G. Alain

In other rock-related news, Europe's oldest known intentional cave engravings were unearthed in France in 2023. Archaeologists found eight panels in La Roche-Cotard cave, which lies some 150 miles (240km) southwest of Paris in the Loire Valley, showing more than 400 Neanderthal 'finger flutings' (indents made by fingers smudged into the sediment). At between 57,000 and 75,000 years old, the panels are among the most ancient engravings ever found.

Iron Age fortifications, Israel

EMMANUEL DUNAND/AFP/Getty Images

Archaeologists from the Israel Antiquities Authority unearthed a missing section of Jerusalem's Iron Age city walls in July 2021. Built some 2,700 years ago, the ruins are believed to be part of a much larger fortification that once defended the eastern slopes of Old Jerusalem. The walls fell with the Babylonian conquest of 586 BC, when Nebuchadnezzar II besieged the city. Alongside the remnants of the prehistoric walls, experts found a stone Babylonian stamp seal, a bulla bearing a Judean name and various storage jars.

Bronze Age barrow cemetery, England, UK

Cotswold Archaeology

In the same English county that gave us Stonehenge, experts unearthed an early Bronze Age barrow cemetery in May 2023, containing at least 20 burials from between 2400 and 1500 BC. The Wiltshire site, on the outskirts of Salisbury, would have once consisted of large artificial mounds surrounded by ditches where the dead were laid to rest, as per tradition dating back to Neolithic times. But as the ground has levelled out over the centuries, only the ditches survive today. Nevertheless, archaeologists have been able to access a number of barrows, including an ancient mass grave.

Extremely ancient human footprints, Germany

Senckenberg

The footprints of a prehistoric family of Heidelberg people were recently uncovered in the Lower Saxony region of Germany. Made 300,000 years ago, the tracks were discovered in Schoningen alongside those of a primeval elephant, and are thought to belong to Homo heidelbergensis – an archaic human species that remain the earliest known home-builders and big-game hunters to walk the Earth. They went extinct around 200,000 years ago, due to climate change.

Ground sloth bone pendant, Brazil

Markus Trienke/Wikimedia Commons/CC BY-SA 2.0

In early 2023, the discovery of a pendant fashioned from the bones of a now-extinct ground sloth pushed back the estimated arrival of humans in South America to around 27,000 years ago. Found in the Santa Elina rock shelter in central Brazil, the bones were punctured with tiny holes that could only have been created by humans, making the pendant the earliest known evidence of human occupation on the continent. Prior to this, the Toca da Tira Peia rock shelter in eastern Brazil placed humans in South America around 22,000 years ago. Pictured here is a skeleton cast of a giant ground sloth at London's Natural History Museum.

Megalithic funerary monument, Spain

M. Angel Blanco de la Rubia

Antequera, a UNESCO World Heritage Site in southern Spain, is renowned for its megalithic tombs from the Neolithic and Bronze Age. In a 2023 study published by the journal Antiquity, researchers announced the finding of a previously undiscovered funerary monument at the site, dating from the 3rd or 4th millennium BC. Overlooked by the limestone shard of La Pena de los Enamorados ('Lover's Rock'), the new tomb is described in the study as "part natural monument, part hypogeum, part megalith". It contained human bones, animal remains and ceramics, and was built to align with the summer solstice sun.

Bronze Age mosaics, Turkey

ADEM ALTAN/AFP/Getty Images

The Hittites were a Bronze Age civilisation who lived in what is now Turkey. In September 2021, experts uncovered some amazing evidence of their little-known culture in Usakli Hoyuk, an archaeological site right in the centre of the country. Found within the ruins of a 15th-century BC temple dedicated to Teshub (god of the weather) was an ancient mosaic, featuring thousands of small beige, red and black stones presented in geometric patterns. The find predates the oldest known mosaics of ancient Greece by seven centuries.

Ice Age human settlement, Oregon, USA

Bureau of Land Management Oregon and Washington/Flickr/CC BY 2.0

Archaeologists excavating the Rimrock Draw Rockshelter in Oregon announced in 2023 that humans were living and hunting in the Pacific Northwest far earlier than first thought. The finding was shared after stone tools caked in dried bison blood and the remains of a prehistoric camel were unearthed at the site, which is thousands of years older than any other archaeological site in the state. The blood-encrusted tool was salvaged from beneath a layer of volcanic sediment formed during the eruption of Mount St Helens 15,400 years ago, while the carbon-dating of the camel's tooth enamel suggests humans used Rimrock Draw 18,250 years ago.

Iron Age golden hoard, Denmark

Konserveringscenter Vejle/Facebook

Amateur detectorist Ole Ginnerup Schytz unwittingly uncovered one of the largest, richest and most beautiful gold treasures in Danish history in 2021, mere hours after stepping out with a new machine in a field near the town of Jelling. The hoard of Iron Age gold weighed almost a kilogramme, and dripped with medallions, coins and jewellery, possibly buried for safekeeping during enemy raids or as a sacrifice to the Norse gods. It was "the epitome of pure luck," said Schytz. "Denmark is 16,600 square miles (43,000sq km), and then I happened to put the detector exactly where this find was." The Vejle Museum in Jutland excavated the find and has been displaying it in its collection since February 2022.

Carraig a Mhaistin stone, Ireland

robertharding/Alamy Stock Photo

For years this partly submerged monument was thought to be an 18th-century folly, an ornamental structure serving no practical purpose. But its history was recently rewritten when research from 2022 identified it as an ancient dolmen – a tomb marked by stacked megaliths dating back to the Stone Age. Located in Rostellan Woods on the eastern shore of Cork Harbour, the Carraig a Mhaistin stone had mystified scientists for decades, but is now listed in guidebooks as one of Ireland’s only inter-tidal portal tombs.

Mesolithic pits, England, UK

MOLA

Twenty-five massive prehistoric pits were found in Bedfordshire, England, in mid-2023. Created between 6,000 and 9,000 years ago during the late Mesolithic era, the site immediately became one of the most important of its kind in Europe, due to its sheer scale. The ancient earthworks, which lie about an hour outside the British capital, would have been made by hunter-gatherers and were scattered with the remains of various animals, including deer, boar, marten and aurochs (a now-extinct genus of wild cattle).

Mycenaean swords, Greece

Greek Ministry of Culture

Perfectly preserved by the sands of time, a trio of bronze swords were unearthed in a prehistoric tomb in 2023 near the Greek town of Aegio in the Peloponnese. Traced back to the Mycenaeans, a late-Bronze Age civilisation that ruled the region and the Aegean Sea between 1700 and 1100 BC, the discovery predates classical Ancient Greece by several centuries. Found within a 12th century BC Mycenaean necropolis, the swords were uncovered alongside an offering of vases, rock crystals, necklaces, beads and gold wreaths.

Stone Age monkey tools, Brazil

Nature Picture Library/Alamy Stock Photo

It was initially thought that this collection of Stone Age tools found across a series of sites in northeast Brazil belonged to early humans. But now experts have presented a new theory: the items were actually made by ancient capuchin monkeys. In a 2022 study, archaeologist Agustin Agnolin and palaeontologist Federico Agnolín concluded that the tools unearthed at Pleistocene sites such as Pedra Furada are consistent with lithic deposits created when modern capuchins use rocks to crack open nuts. It seems it was just monkey business all along...

Earliest evidence of cannibalism, Kenya

Courtesy of Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History

A study published in 2023 by experts from the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History revealed the oldest decisive evidence that our close evolutionary relatives butchered and probably ate one another. The study authors found that cuts inflicted on the tibia (shin bone) of a 1.45 million-year-old relative of Homo sapiens found in northern Kenya corresponded to stone tools wielded by prehistoric humans for the stripping of flesh. These photos show animal bones from the same area and era as the tibia, and they display identical cut marks to the human bone studied by the team.

Natufian flute instruments, Israel

Laurent Davin, CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons

These extraordinary finds from 2023 are the oldest known sound instruments that imitate bird calls. Used by the Natufian people, a late Mesolithic Middle Eastern culture, to mimic the calls of birds of prey, the delicate prehistoric flutes are carved from bird bones, date back 12,000 years, and are among the smallest ancient instruments ever found. They were unearthed in Israel and, while it’s no longer possible to play them, researchers employed special software to construct replicas, finding that they would have sounded like Eurasian sparrowhawks or common kestrels.

Europe’s oldest village, Albania

© Marco Hostettler/Courtesy of Universitat Bern

On the Albanian side of Lake Ohrid, which straddles the North Macedonian-Albanian border, archaeologists have just found what they suspect to be the remains of an 8,000-year-old village – which, if dating tests come back conclusive, would be the earliest known settlement of its kind anywhere in Europe. Unearthing hundreds of tree-trunk stilts on the lakebed, the team believe these formed the foundations of prehistoric residences. Albert Hafner from the University of Bern in Switzerland led the excavations, and has been studying Balkan lakes for several years to try and find traces of the first settlers to bring farming to Europe from Mesopotamia.

Ice Age axes, England, UK

Archaeology South-East/UCL

Why would you craft an axe that's impossible to wield? That was just one of the questions raised when archaeologists discovered a pair of mighty 300,000-year-old handaxes in the English county of Kent. The ungainly weapons were found buried in a hillside in the Medway Valley, where some 800 Stone Age artefacts were also uncovered. Letty Ingrey, senior archaeologist at the UCL Institute of Archaeology, suggested that the axes might have fulfilled more of a symbolic purpose than a practical one, since they're almost a foot long and too heavy to use. The longer of the two is one of the biggest axes ever found in Britain.

3,000-year-old weavings, Alaska, USA

© Alutiiq Museum

In August 2023, archaeologists from the Alutiiq Museum and Archaeological Repository in Alaska were excavating a burnt-down ancient sod house on Kodiak Island when they uncovered scraps of 3,000-year-old woven-grass floor mats. Found on the shores of Karluk Lake, the discovery marks the oldest well-documented examples of Kodiak Alutiiq weaving, a long-practiced Alutiiq art form. The Alutiiq (also known by their ancestral name Sugpiaq) are one of eight Native Alaskan peoples, whose history in this coastal region dates back over 7,500 years.

Neolithic cursus, Scotland, UK

Malt House Photography/Alamy

On the Isle of Arran, off the west coast of Scotland, scientists and a team of local volunteers recently unearthed what is said to be the only complete Neolithic cursus monument found in Britain. These rectangular enclosures, made of stone, earth and turf, would have played a part in ancient ceremonies, gatherings and processions. Predominantly, they were created for spectacle. The Arran cursus (only 1% of which has been excavated at the time of writing) lies near the stone circles of Machrie Moor (pictured). It’s thought that the location was intended to lead people from the coast up into the island’s scenic interior.

Copper Age mummy’s genetics, Italy

Andrea Solero/AFP via Getty Images

A 5,300-year-old mummy frozen in ice – and affectionately known as Otzi – was found by unsuspecting German hikers in the Tyrolean Alps in 1991. Much has since been discovered about the Copper Age iceman, and a recent genetic study published in August 2023 broke new ground by painting a picture of what he would have looked like in life. Otzi’s lineage has been traced back to Anatolia (modern Turkey), and he was likely descended from farmers who emigrated to Europe some 9,000 years ago. The study also suggests Otzi was brown-eyed and middle-aged, with dark skin pigmentation and a receding hairline.

Burned Neolithic porridge, Germany

BIAX/W. van der Meer/CC BY 4.0

Ever wondered what Stone Age people had for breakfast? Turns out the answer is porridge. These remnants of burned porridge found inside a ceramic pot are thought to be 5,000 years old. The unusual find from January 2024 was discovered in a pile of rubbish unearthed at the Neolithic settlement of Oldenburg LA 7, thought to be one of the oldest villages in Germany. Experts who examined the meal mishap and its vessel detected traces of seeds and cereal grains, revealing how diverse the Neolithic diet was.

Prehistoric monument, France

JEROME BERTHET/INRAP

A mysterious prehistoric monument has been uncovered by architects in Marliens, a commune in eastern France. According to Live Science and the French National Institute of Preventive Archaeological Research in April 2024, the discovery has been described as "unprecedented". Resembling an incomplete bow tie, researchers are unsure of its age but say other excavations at the same site revealed artefacts spanning thousands of years from the Neolithic period to the Iron Age. The nature and the purpose of the monument remain unknown.

Mysterious ritual site, Crete, Greece

Greek Ministry of Culture

A 4,000-year-old structure on the Greek island of Crete baffled archaeologists when it was unearthed in June 2024. The hilltop structure, which belonged to the Minoan civilisation and was used between 2000 and 1700 BC, has halted the construction of a new airport in the Papoura Hill area, northwest of Kastelli. Experts are not sure what the huge stone structure, measuring around 157 feet (48m) is diameter, functioned as, but since animal bones were also found nearby, they're suggesting it could've been used for ritual or religious purposes. More excavations are needed to determine the main purpose of such a unique site.

Now discover the world's most intact archaeological discoveries, ranked