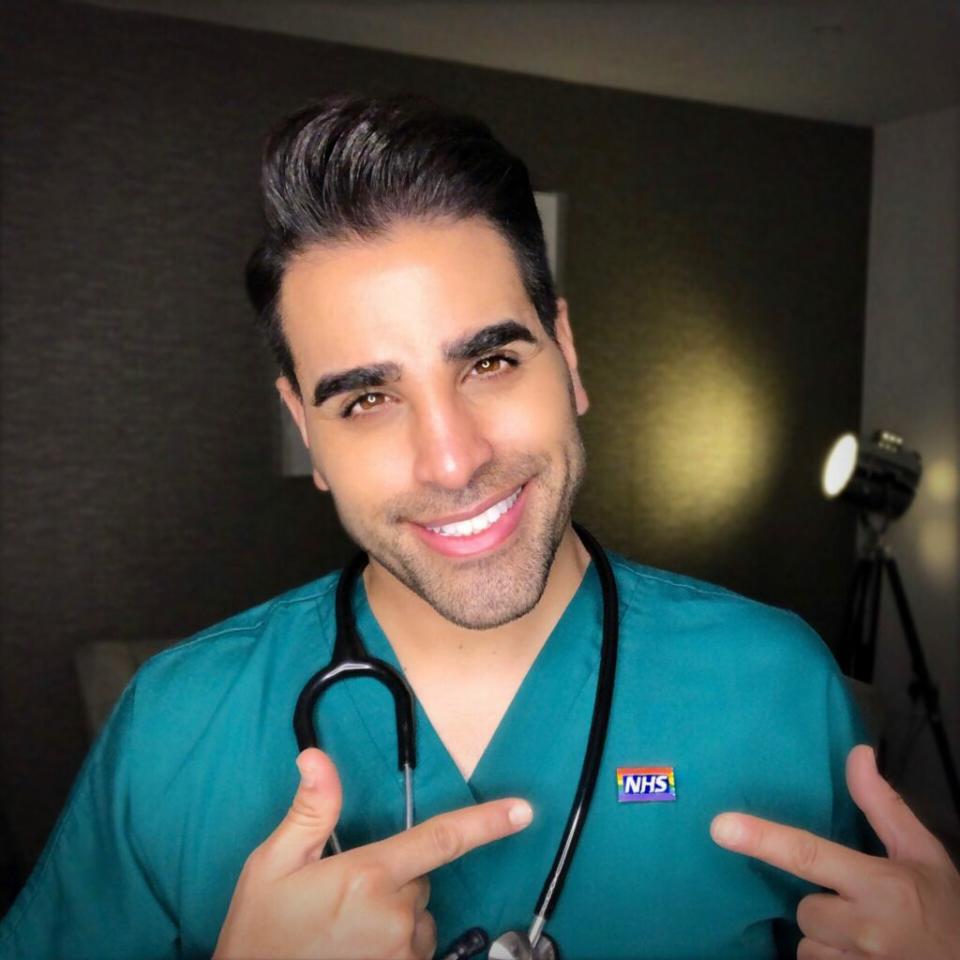

From HIV to transitioning, Dr Ranj Singh reflects on 30 years of LGBTQ+ healthcare

Since I started medical school almost 30 years ago — and qualified 10 years later — I’ve seen so much change, particularly when it comes to LGBTQ+ healthcare. And yet we still have so much to do. As Attitude celebrates its 30th anniversary, and February’s theme for LGBTQ+ History Month 2024 was medicine and healthcare “under the scope”, it feels pertinent to look back on some of the biggest advances we have made so far.

So much of LGBTQ+ history is intertwined with health and wellbeing. We are a community that has been — and still is — disproportionately affected by certain conditions, both physical and mental. But at the same time, members of the community have also been responsible for some of the biggest contributions in these fields.

HIV/AIDS care

The work done to battle HIV and AIDS has led to the most notable developments in LGBTQ+-related care we have ever seen.

After the first cases were detected in the 80s, HIV/AIDS was initially dubbed GRID (Gay-Related Immune Deficiency). If you watched It’s a Sin, or indeed you lived through the 80s, you’ll know about the devastation HIV/AIDS has caused. The era was marked by the proliferation of terms like the ‘gay plague’, reflecting how the virus spread more easily among men who engaged in same-sex relations. The impact, particularly for gay and bisexual men in that decade and beyond, was significant, and the ripple effect is still felt today.

In 1986, the UK government launched a nationwide HIV/AIDS education campaign, also known as the ‘Don’t die of ignorance’ or ‘tombstone’ campaign after the imagery it used. It sought to arm every household in the country with essential information about AIDS. Widely hailed as one of the most impactful advertising campaigns ever, it had a lasting effect on STI transmission in the UK. But at the same time, its petrifying imagery contributed towards terrifying a generation of young gay men and stigmatising their sexuality.

1995/1996 One of the biggest breakthroughs against HIV and AIDS arrives in the form of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART). It offers renewed hope and extends lives, transforming HIV/AIDS from a grim prognosis to a manageable chronic condition. Triple combination therapy using antiviral drugs becomes standard, and the viral load test is developed, providing vital information about disease progression.

2005 Antiretrovirals begin to be refashioned as a post-exposure HIV treatment for those who may have become inadvertently exposed to the virus, to reduce their chances of it taking hold.

2012 In a big leap forwards, Truvada is approved as a pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP). Research shows that if HIV-negative individuals take certain antiretroviral drugs regularly, they can reduce the risk of HIV infection if they are exposed to the virus. It is also discovered that if people living with HIV are placed on early treatment, before the virus has a chance to damage the immune system, and their levels of HIV reduce to undetectable levels, then they cannot pass the virus on. U = U (undetectable = untransmissible), as it is commonly advertised, shows that HIV-positive people can live normal, healthy lives without developing AIDS. We finally have a way to stop HIV in its tracks.

2024 Currently, in the UK, 97 per cent of people with HIV are on effective treatment and cannot pass on the virus, and we are on track to stop new transmissions entirely by 2030. This success has only come from pioneering work by the NHS, organisations like the Terrence Higgins Trust and the National AIDS Trust, and efforts by the LGBTQ+ community. Now, work needs to be done for other groups, especially heterosexual people and ethnic communities, including increased efforts to end HIV-related stigma.

Mental health support

It’s no secret that LGBTQ+ individuals are more likely to experience mental health challenges such as depression, anxiety, and suicidal ideation due to historical and current stigma, discrimination, and rejection.

1992 The UK declassifies homosexuality as a mental illness. This decades-overdue change occurs with the publication of ICD-10, the World Health Organization’s International Classification of Diseases publication, which removes homosexuality from its list of mental disorders. Disgracefully, we lag nearly 20 years behind America, where it had been declassified in 1973 in the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders.

2019 Transgenderism, or gender dysphoria, as it is clinically referred to, is declassified as a mental illness in the UK with the publication of the World Health Organization’s ICD-11. These changes are significant milestones in the recognition and acceptance of LGBTQ+ people, both within the medical community and society at large. Greater understanding has also led to increased access to mental health services tailored to our community’s needs.

2024 A combination of LGBTQ+-affirmative therapy (which acknowledges and validates individuals’ sexual orientation, gender identity, and expression), legal and policy changes (such as anti-discrimination laws, marriage equality, and protections for transgender individuals), and increased research and advocacy efforts focused on LGBTQ+ mental health, have all helped to promote LGBTQ+ mental health and wellbeing. However surveys still consistently show how ongoing stigma, a lack of suitable health and wellbeing services, and social exclusion all contribute to poorer rates of mental health among the LGBTQ+ community when compared with our heterosexual counterparts, demonstrating that there is still much work to be done.

‘Conversion therapy’

Over the past three decades, so-called ‘conversion therapy’ has continued to exist, despite growing awareness of the damage

it does.

1990s/2000s So-called ‘conversion therapy’ continues to be promoted by certain religious groups and fringe practitioners, perpetuating harmful beliefs about LGBTQ+ identities.

As awareness of the harm it does grows, efforts to combat it increase. LGBTQ+ advocacy groups, survivors and allies push for legislative action to ban so-called ‘conversion therapy’ for minors, citing evidence of its ineffectiveness and potential for inflicting psychological trauma.

2018 The UK government announces its intention to ban so-called ‘conversion therapy’, acknowledging the practice as both ineffective and harmful. However, concrete legislative action is then delayed, leading to frustration among LGBTQ+ advocacy groups and supporters. Despite setbacks, momentum against so-called ‘conversion therapy’ continues to build, with numerous professional bodies, including the UK Council for Psychotherapy and the British Psychological Society, publicly condemning

the practice.

2021 In July, the UK government again announces plans to introduce legislation banning so-called ‘conversion therapy’, with a focus on protecting minors from harm. However, the proposed legislation faces criticism for its scope and potential loopholes, prompting calls for a more comprehensive ban, particularly with regard to trans people.

2022 It is leaked that plans for a ban are being dropped by the government. The backlash leads the government to recommit to a ban — but not for trans people. The government later confirms the ban won’t include trans people or “consenting adults”.

2023 The government announces plans for a ‘conversion therapy’ ban inclusive of trans people. However, there are further delays before the ban is dropped from the King’s Speech in November. After this, Members of Parliament and Members of the House of Lords introduce separate bills, both aimed at banning the practice.

2024 We are still waiting…

Transgender care

Despite challenges from certain parts of society, there has been significant progress in expanding access to gender-affirming care for transgender and gender-nonconforming people. However, even though they represent less than 1 percent of the population, our trans siblings constantly face unacceptable discrimination, harassment, and debate about their existence and identity.

1990s Transgender healthcare is still in its infancy, and many healthcare providers lack understanding of transgender health issues. I certainly don’t remember being taught much about the subject in medical school.

2000s Through the work of the transgender community and advocacy organisations, this decade sees increased awareness. Medical organisations such as the World Professional Association for Transgender Health (WPATH) develop guidelines for transgender healthcare. Gender-affirming treatments, including hormone therapy and surgery, start to become more widely available. There is now also a greater emphasis on holistic transgender healthcare, including mental health support, sexual health services and social support networks.

2018 A Stonewall report suggests progress is limited, with the news that two in five trans people in the UK say healthcare staff lack understanding of their needs, while approximately 24 per cent fear discrimination and do not know how to access transition-related healthcare.

2020 The UK government commissions an independent review into gender identity services for children and young people, chaired by Dr Hilary Cass. This reflects the rapidly increasing demand for gender-related services against the reality of a lack of provision, research, and evidence to match, with a particular focus on the treatment of transgender children and young people.

2022 The review publishes an interim report. At this time, there is a single specialist service providing gender identity services for children and young people: the Gender Identity Development Service (GIDS) at the Tavistock and Portman NHS Foundation Trust in London. The review finds that there isn’t just a widespread disparity in terms of access to transgender-related care for young people, but also no consistent approach or agreement on how they should be treated. It recommends changing the model of care currently provided, including medical treatments. It also suggests a more regional model rather than relying on the Tavistock clinic alone.

2024 Ahead of the independent review’s findings, NHS England announces a pause on prescribing puberty blockers for children, citing “not enough evidence” to support their safe usage or clinical effectiveness. The Gender Identity Development Service (GIDS) at the Tavistock and Portman NHS Foundation Trust closes. In its place, two new centres, one in London and another in Liverpool, are set to open soon.

Inclusive healthcare

One of the biggest changes during my time in healthcare is the change in attitudes towards making it more inclusive. Many healthcare institutions have adopted policies explicitly prohibiting discrimination based on sexual orientation and gender identity. These policies create safer and more welcoming environments for LGBTQ+ patients and help ensure that they receive appropriate and equitable care.

2018 The NHS Rainbow Badge is introduced. This is the idea of Dr Michael Farquhar, one of my colleagues at the Evelina London Children’s Hospital. Inspired by similar initiatives in other sectors, it is launched in response to concerns about the discrimination and inequalities faced by LGBTQ+ individuals in healthcare settings. It aims to foster a culture of respect, dignity and understanding for LGBTQ+ patients and staff members, and to challenge stigma and discrimination based on sexual orientation, gender identity or expression. In short: wearing the badge tells our LGBTQ+ patients that we are safe people to talk to and be themselves with, and that we will do our best to provide the care they need and deserve, regardless of who they are.

2021 The NHS Rainbow Badge initiative is adopted by hospitals across the UK, reflecting the success of the scheme. Later in 2021, the project is taken over by NHS England, with the support of organisations like Stonewall and the LGBT Foundation. The aim is to roll it out further with a new scheme to benchmark and award NHS organisations for their work on LGBT+ inclusion.

2024 The NHS Rainbow Badge Partnership announces its conclusion due to a lack of government funding. Although many UK hospitals have adopted the Rainbow Badge, this development means that expansion has been paused for now. It has been a heart-breaking setback for everyone committed to creating a more inclusive health service. However, the impact it has had so far, and continues to have, will never be lost.

The future of LGBTQ+ healthcare

There is so much more to explore and celebrate, with further developments on the horizon. Although these advances mark significant progress, challenges persist. These include ongoing inequalities in healthcare access and outcomes, discrimination and the ongoing need for advocacy and education to ensure fair healthcare for all LGBTQ+ people. Fortunately, there are amazing individuals among the community, as well as our allies, who are fighting for conditions to be better for everyone. And that fills me with hope.

This issue was originally featured in Attitude issue 358 – available here.

The post From HIV to transitioning, Dr Ranj Singh reflects on 30 years of LGBTQ+ healthcare appeared first on Attitude.