When I heard my son had a benign brain tumor at 11, I thought that meant it was harmless. I was wrong.

When my son was 11, we found out he had a benign brain tumor.

Soon, I learned the word "benign" didn't mean harmless, as I'd previously thought.

The tumor was inoperable, but they did surgery to treat his hydrocephalus, with a slow recovery.

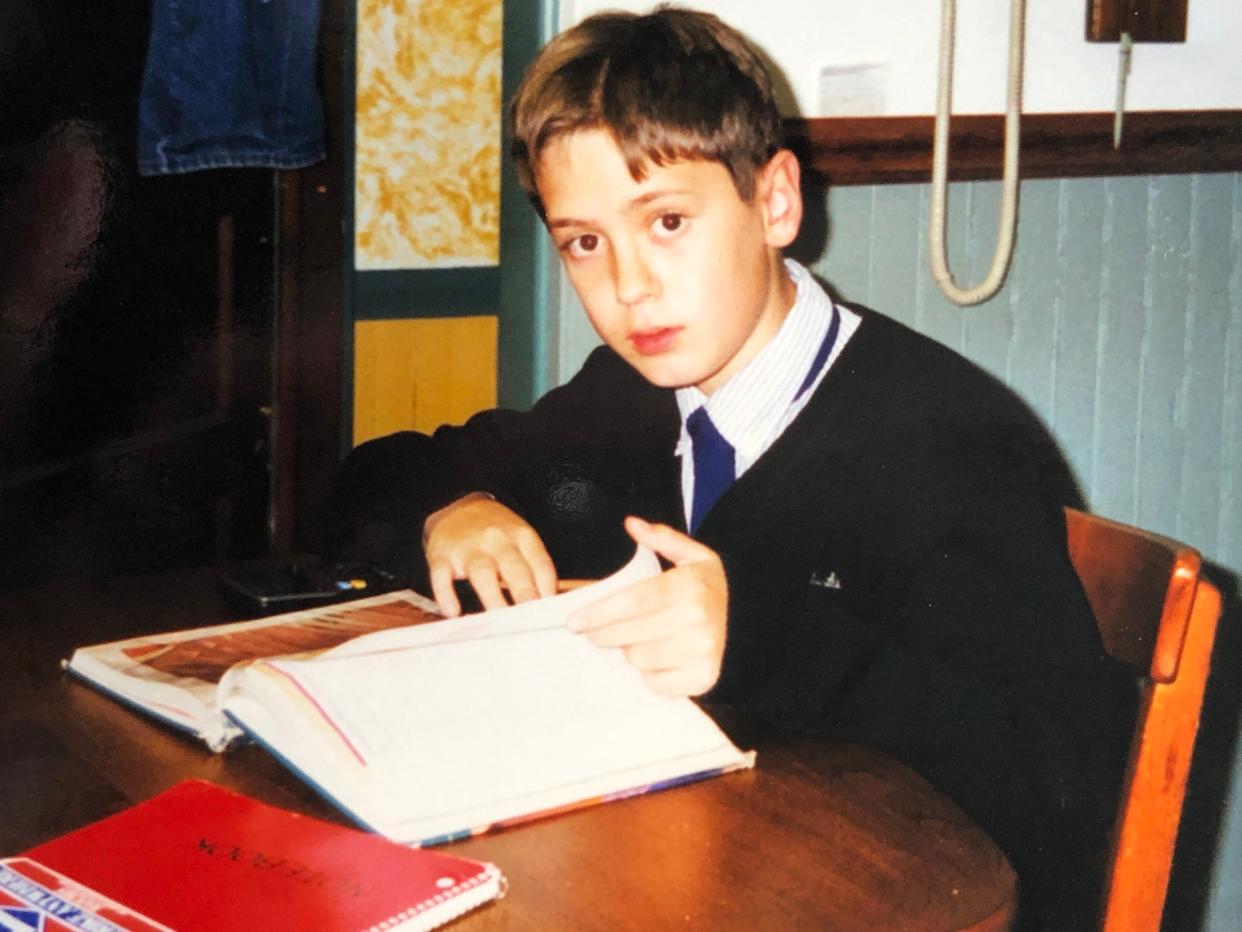

At 11, my son was mature enough to understand why doctors wanted to take pictures of his brain and trusting enough of his parents to do whatever we said was necessary.

I'd never had an MRI, but I knew what the procedure entailed. Picturing the narrow hole that swallows the occupant of the machine brought to mind the confines of a submarine or rocket.

"It's cool, like a spaceship," I told Matthew, as much to allay my fears as to prevent his.

As a younger child, Matthew could hardly sit still at home. He'd climb trees in our backyard, clown around for a camera, and run from room to room in his Superman pajamas. Yet when he worked on a task like building a Lego spaceship, he was laser-focused. Well behaved in school and a straight-A student, he earned a spot in the gifted program.

At 8, he developed facial tics, and his energy started to wane. Over the next three years, his motor tics piled on, his grades tanked, and he became clumsy, easily tired, and forgetful. We took him to myriad specialists, and none of their diagnostic hypotheses panned out. I didn't expect much of this MRI; it was simply another test to rule out something sinister.

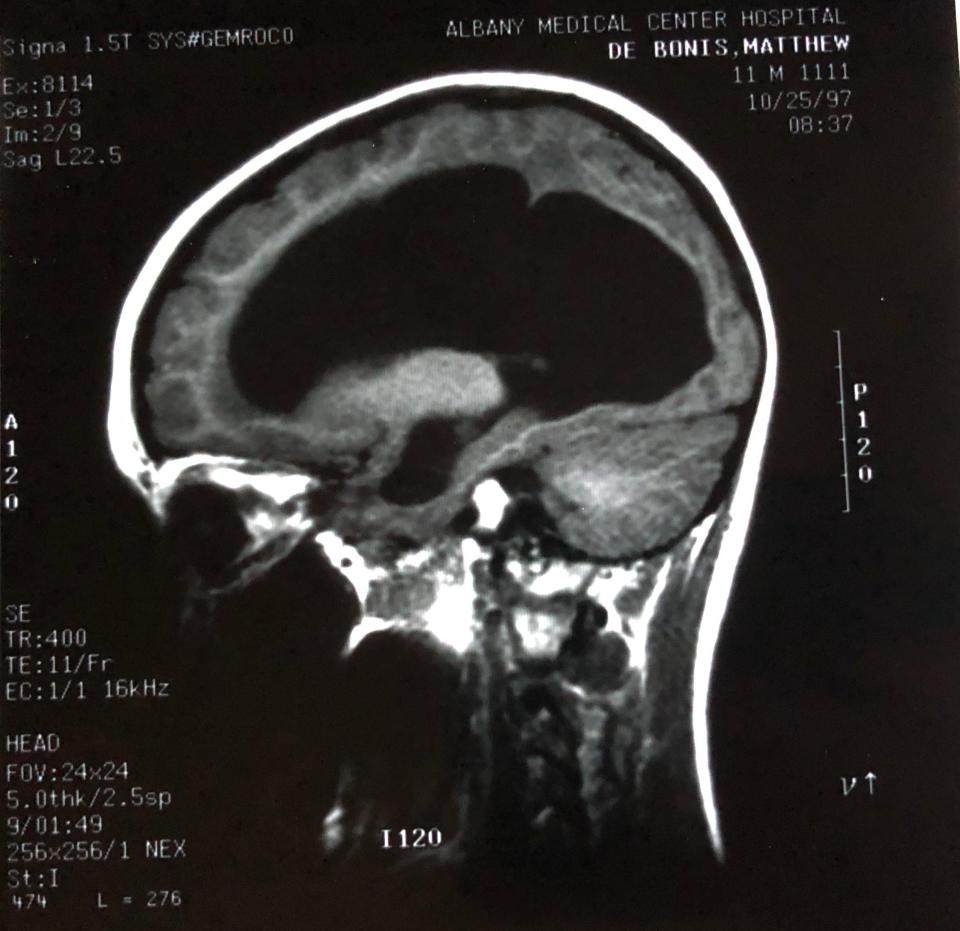

Less than an hour after I tucked in Matthew on the gurney, my husband, Mike, and I squeezed into a lab room among several technicians and a thin, white-coated man introduced himself as the radiologist. After an agonizing moment of silence, he spoke.

"We found a growth," he said.

It would be hours before I absorbed the true meaning of the euphemism: Matthew had a brain tumor.

Understanding what Matthew's tumor meant for his future

That morning in October 1997, my son became one of an estimated 700,000 Americans living with brain and central-nervous-system tumors. This year, almost 4,000 new cases of primary childhood brain tumors are expected to be diagnosed in children ages 0 to 14.

The club of unwilling members represents those with 140 types of brain tumors, which have a dizzying array of symptoms, treatments, and outcomes. Headaches and seizures are two of the most common symptoms, yet Matthew experienced neither, validating that each patient presents in a unique way. The way his presented, unfortunately, is part of why his diagnosis took so long.

The absence of typical clues, along with the fact that facial and motor tics, forgetfulness, and disorganization are common in healthy school-age children, contributed to his being undiagnosed for two years. Another factor in Matthew's delayed diagnosis: our pediatrician's unwillingness to validate my concerns. My self-doubt and fear of conflict added to the destructive dynamic.

I finally took Matthew to a psychologist, who diagnosed him with attention-deficit disorder, which felt like a reasonable diagnosis at the time. As Matthew continued to deteriorate, the specialists and diagnostic hypotheses snowballed to include muscular dystrophy, Tourette syndrome, and even schizoid personality disorder.

The radiologist had more to say. Pointing to a computer monitor, he explained that the growth — which at the time was the size and shape of a kidney bean — clung to Matthew's brain stem, a structure deep inside the brain that controls and regulates vital bodily functions, including respiration, heart rate, and blood pressure.

"It's inoperable," he said, "but benign." The word "benign" kept me upright that day. Everything I knew about that word told me what he'd just said meant the tumor wasn't cancerous. In my lay world, "benign" also meant harmless. I was wrong.

Learning the difference between benign and malignant

Sometime in the blur following Matthew's diagnosis, the neurosurgeon on call one day told us it didn't matter whether a brain tumor was benign or malignant. With no additional explanation, his words made no sense and were too scary to consider, especially when I'd just begun to have hope. Thus, I didn't investigate the full meaning of his words until years later.

When I did, I learned that even if a growth in the brain did not invade and damage healthy cells — characteristics of a malignancy — it could crowd and damage structures of the brain that enable us to breathe, think, move, and feel. For a child, whose brain is still growing and forming connections, the danger is magnified.

This means that even a benign brain tumor can be deadly. For this reason, the American Brain Tumor Association prefers the term "nonmalignant" to make a distinction between the way they act.

My misunderstanding of benign wasn't the only wrong assumption I'd made about Matthew's condition. The neurosurgeon told us Matthew had a pilocytic astrocytoma, a low-grade, slow-growing mass, rare in itself but common among brain tumors in children. Like most kids, the doctor said, Matthew would "bounce back." The more I learned, the more I thought, "If my child must have a brain tumor, this is the one to have."

But the danger in Matthew's pilocytic astrocytoma lay in its location. It trapped cerebral spinal fluid in the ventricles — the four cavities in the brain — and expanded them like water balloons, a condition called hydrocephalus.

I had heard of babies being born with "water on the brain," but I didn't know it could happen in older children; in fact, it can even happen in adults. Matthew's hydrocephalus was so severe that it squished his gray matter into a sliver against his skull. Every part of his brain was affected, which explained his cognitive, motor, and emotional decline over the previous three years.

Figuring out the right treatment — and the aftermath

While Matthew's tumor itself was inoperable, the recommended treatment for his hydrocephalus was a novel surgery — an endoscopic third ventriculostomy. I understood only the basics: The neurosurgeon would poke a hole in the third ventricle, and the excess fluid would drip away to be absorbed by the body. Unless the tumor grew significantly, which was not expected, chemotherapy and radiation wouldn't be necessary.

After Matthew's surgery and two-night hospital stay, I believed that the nightmarish medical mystery we'd been going through since he was 8 years old was solved. I believed our life of contentment would return.

Wrong again: It took about a year for us to realize Matthew's bouncing back would be more like a slow dribble. His brain had been under siege for too long; the hydrocephalus had caused too much damage.

Often, patients and survivors of both benign and cancerous brain tumors bear visible evidence of their ordeal — surgical scars, as well as physical, cognitive, and behavioral impairments. Many of the 700,000 Americans living with a brain tumor look healthy but struggle with a variety of aftereffects, including anxiety and confusion, memory difficulties, fatigue, and depression. Like Matthew, other survivors may also suffer from a lack of executive-functioning skills, which help work toward goals and plan with big-picture-type thinking.

Post-surgery, Matthew functioned too well to qualify for rehabilitation programs, yet his struggle to get through each day weighed heavily on our family. I left my job to support his recovery, convinced it was the only way he'd get through school. With the help of a 504 education plan, supportive teachers, and my full-time cheerleading, he bumbled through middle school and then graduated from high school.

Then he earned his four-year college diploma, entered the workforce, and eventually bought a house on his own. Today, Matthew's impairments — I call them hiccups — are mild, most apparent when he is tired, stressed, or overloaded by information. If you didn't know, you'd never suspect what he has overcome.

You may not think you know a person with a brain tumor, but maybe you do. You never know what's making their lives difficult, what invisible affliction makes it hard to get through their day.

If you are one of the 700,000 Americans living with a brain tumor, know that you are seen, that you are not alone. If you are a loved one, know that others understand your frustration and impatience. Know that we, too, hate the tumor but love the person. Most likely, our loved ones are doing the best they can with the "benign" hand they were dealt. And we are doing the best we can to support them.

Read the original article on Insider