Healing, grace and enlightenment: How Pharoah Sanders and Floating Points made a spiritual album for the dark ages

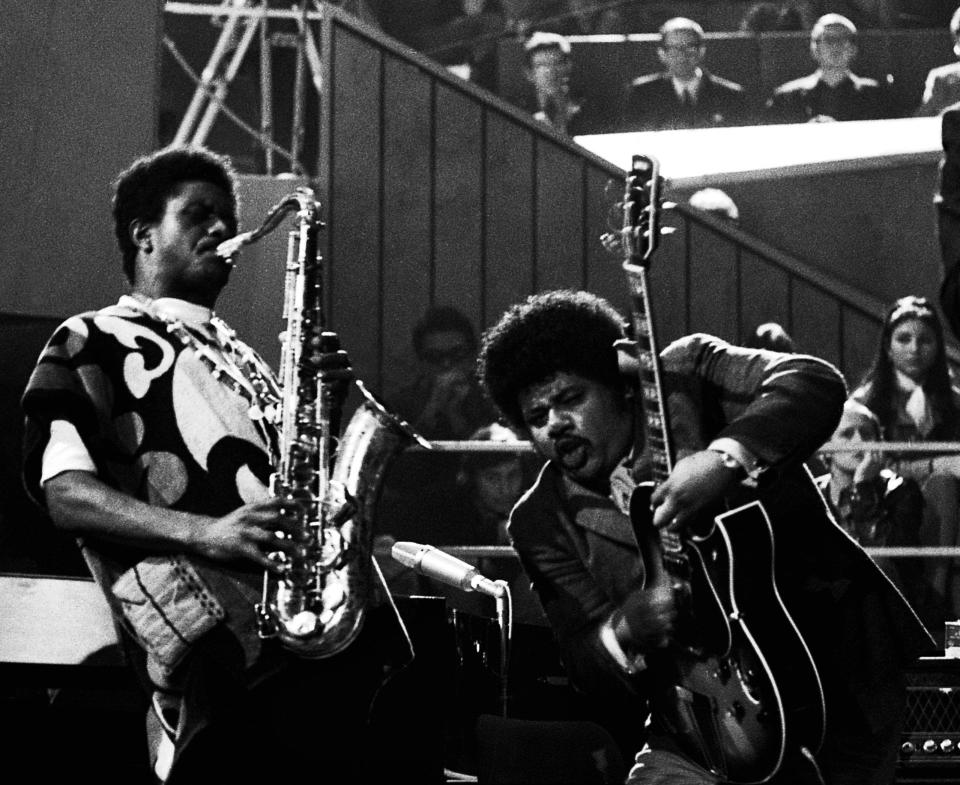

Pharoah Sanders (left) with DJ Sam Shepherd, aka Floating Points

(Eric Welles-Nystrom)It may be too early to talk about albums of the year, but Promises, the new collaboration between British DJ-producer Floating Points, aka Sam Shepherd, and American saxophonist Pharoah Sanders has already garnered enough glowing reviews, from both mainstream pop and specialist press, to make it a prime candidate for the top spot. The music has a real grace to counter our troubled times, and pulls as much from the jazz world as it does the classical and electronic ones.

A generational as well as stylistic line has been crossed, too. Sanders is now 80 and Shepherd, 34. The latter is a bespectacled, clean-shaven figure hunched over a mixing desk; the former holds a golden horn high in the air, his silver goatee hanging low after decades of growth. But despite the considerable age gap between them, there are reasons why they might find common ground.

Sanders is a living legend whose career stretches right back to the mid Sixties. He’s one of founding fathers of “spiritual jazz”, which has had a sizable impact on global audiences in the past few years for its graceful blend of intense soloing and messages of enlightenment and healing. He brings a degree of absolute authenticity to the idiom.

Shepherd’s finely stitched ambient soundscapes, meanwhile, may reflect his allegiance to classical composers such as Ravel and Debussy, as much as a love of club music, but he has also been vocal about the inspiration that he draws from jazz. He has dropped no greater clue than playing the timeless 1977 Sanders piece “Harvest Time” at techno clubs such as Berghain in Berlin.

Lasting just over 20 minutes, the song has the balmy, meditative if not incantatory quality of the highlights of Promises, and can be seen as a loose conceptual foretelling of it. Sanders actually doesn’t listen to much music these days, but he heard Floating Points on his car radio and found something to which he could relate. Tellingly, this is the first time he has recorded in some 20 years.

The fact that Shepherd has also brought the London Symphony Orchestra to the project simply underlines how breathtakingly lyrical a player Sanders is. Against the languorous swathes of strings and cascades of piano or synth, the saxophonist makes his tone flicker gently or fire up with energy without ever losing control, as befits a master craftsman who is way beyond any attention-seeking antics.

The ancestral, dawn-of-time gravitas of Sanders’s playing is now more readily acknowledged than ever. At last year’s London jazz festival, Cassie Kinoshi, saxophonist and leader of Mercury Music prize nominee Seed Ensemble, performed a concert in his honour, featuring new arrangements of his music, while in 2017 Sanders appeared at the same festival as part of a triple bill, in which he was supported by two excellent UK-based artists, saxophonist Denys Baptiste and harpist Alina Bzhezhinska. The significance of that performance is not to be played down. It was a grand celebration of Sanders, and by extension the legendary musicians with whom he was closely associated and who wrote a highly significant new chapter of jazz history in the mid Sixties.

In particular, those were jazz greats John and Alice Coltrane. Sanders greatly learnt from and played with both. The albums the husband and wife recorded together, 1968’s Cosmic Music, and under their own names – above all his A Love Supreme and her Journey In Satchidananda, to which Sanders made a quite brilliant contribution – laid the foundation for a distinct sub-genre known as “spiritual jazz” that has steadily grown in influence over the decades. It has become a part of the core vocabulary of many artists drawn to its wholly compelling blend of emotional charge and textural richness.

For the most part, the aforementioned works do have common structural characteristics such as a harmonic basis in modes or scales. Basslines are steadily repeated and unbroken ripples of percussion add to the sense of an eternal life cycle of sound. Melodies tend to be short and solos long, with the musician impelled by a desire, if not obsessive quest, to express something profound or idealistic, be it a vision of peace on earth, selflessness or “universal consciousness” or, perhaps, attempting to commune with a higher power.

Although non-western belief systems and timbres, especially those of India, are often prevalent in spiritual jazz, the genre has something innately African-American insofar as it resonates with the far-reaching tradition of the “negro spiritual”, the antecedent of gospel, one of the cornerstones of black diasporic music. When growing up in Little Rock, Arkansas, Sanders learnt hymns and played clarinet in his local church. Many of his songs acknowledge the redemptive power of the Almighty, and he makes serious statements about the betterment of humanity that speak to those who see no real border between culture and activism.

Sanders has indeed become a musical preacher and prophet of sorts.

He can do slow, sensual mantras and hard, fleet-footed swing, often with intensely volcanic overtones on the saxophone. Between the late Sixties and early Eighties, he recorded a string of epic, engrossing, songs, from “Let Us Go Into the House of the Lord” and ‘“The Creator Has a Master Plan” to “Prince of Peace” and “You’ve Got to Have Freedom”, which have been turning heads on the British club scene since the early Nineties. And they in turn, influenced consecutive generations of artists. The group Galliano, a notable exponent of “acid jazz”, a novel mix of hip-hop, jazz and soul that came to prominence during that Nineties club era, reprised Sanders’s blissful melodies, while in the 2000s the celestial serenity of his work with Alice Coltrane helped to shape producer-led groups such as The Cinematic Orchestra.

The music created by a wide variety of artists in the few years as part of what’s been called the new UK jazz scene, from saxophonists Nubya Garcia and Nat Birchall to bands such as Maisha and Sons of Kemet, led by Shabaka Hutchings, has made the legacy of Sanders (and the Coltranes) all the more resonant.

Barbadian-British saxophonist Hutchings, an emblematic figure of contemporary jazz, has always been emphatic in his recognition of these trailblazers, waxing particularly lyrical about seeing Sanders in concert: ”I was struck by his poise,” he wrote in a blog for record label-cum-magazine The Vinyl Factory. “It seemed as though he was rooted to the ground and was able to draw power from throughout his whole body to be channeled through the saxophone.”

One imagines that Sanders himself had a similar experience listening to John Coltrane. The fact that Sanders is now the elder to whom Hutchings and others, such as American saxophonist Kamasi Washington and South African pianist Nduduzo Makhathini, (a member of one of Hutchings’s other bands, Shabaka & The Ancestors), look for inspiration is part of the organic process of passing the torch from one generation to another that is a key characteristic of jazz history.

Sanders remains acutely relevant to modern musicians who value the sound of truth and integrity. Both the ferocity and sensitivity of his tone are beyond the technical reach of many players. But first and foremost what he plays comes from within, an inherently personal space, and there is nothing more moving than the moment his communicative impulse becomes so strong that Sanders puts down his horn and sings an impassioned chorus of “Africa! Africa! Africa!”

In a lengthy, eventful career, Sanders has worked with everybody from Indian tabla masters and Moroccan trance ensembles to Latin and funk bands, so the new collaboration with Floating Points is not a radical departure for him. Rooted as he is in spiritual jazz, the saxophonist has never been restricted by it. Promises, for its otherworldly beauty, could well be a record of 2021. Pharoah Sanders is a 21st-century icon.

Read More

‘It was a breaking down of racial barriers like never before’: Why Brit-funk matters