What Happens After You Get Sober?

There’s a joke in comedian John Mulaney’s recent stand-up special, Baby J, I’ve been thinking about a lot lately. It follows the first weeks of Mulaney’s highly publicized 2021 stint in rehab in, during which he realizes that the staff and everyone alongside him, sharing hisrecovery journey … have absolutely no clue who he is. The bit is eight minutes long, kaleidoscopic, and covers a lot: the self-delusion of fame, Pete Davidson’s phone habits, and the absurd knowledge that while half of Twitter is busy chronicling your epic fall, you’re in a Pennsylvania recovery facility, being treated exactly like what you are—an everyday addict. At a painfully intimate point (“Please don’t repeat this,” he tells a sold-out crowd), Mulaney confesses to leaving a newspaper out in a common area, conspicuously open to a news story about his relapse, quietly begging to be seen.

What’s fascinating isn’t the clear hook of the bit: How does nobody recognize me? It’s the question Mulaney doesn’t ask, and it’s one that Baby J seems to pose at large: “Now that I’m sober, what if I don’t recognize me?” It's a bleak mission statement, and joke after joke, he digs deeper into it and the messy contradictions of his new, sober life. How he’s grateful for the star-studded group that led his intervention, but how he also still kinda hates them for it. How when he looks in a mirror, he sees a person whose life was saved by sobriety, but also a person who almost ended that life.

As an alcoholic eight years into my own day-by-day recovery, I found it thrilling. I’ve watched, read, and found solace in volumes of popular chronicles of people getting sober. The triumph of Ewan McGregor’s Mark Renton “choosing life” in Trainspotting. Denzel Washington’s Whip Whitaker confessing to his alcoholism at a federal testimony in Flight. Don Draper’s newly sober, bizarre epiphany at the end of Mad Men that soft drinks can unite the world. Zendaya’s deadpan Rue Bennett sprinting through a gauntlet of mental health crises and addiction issues before Euphoria’s first title card even hits. These are bold, necessary stories for many reasons, not least among them their role as salvation templates. A way out is possible, they say to the addict or the alcoholic. All you need to do is commit to it.

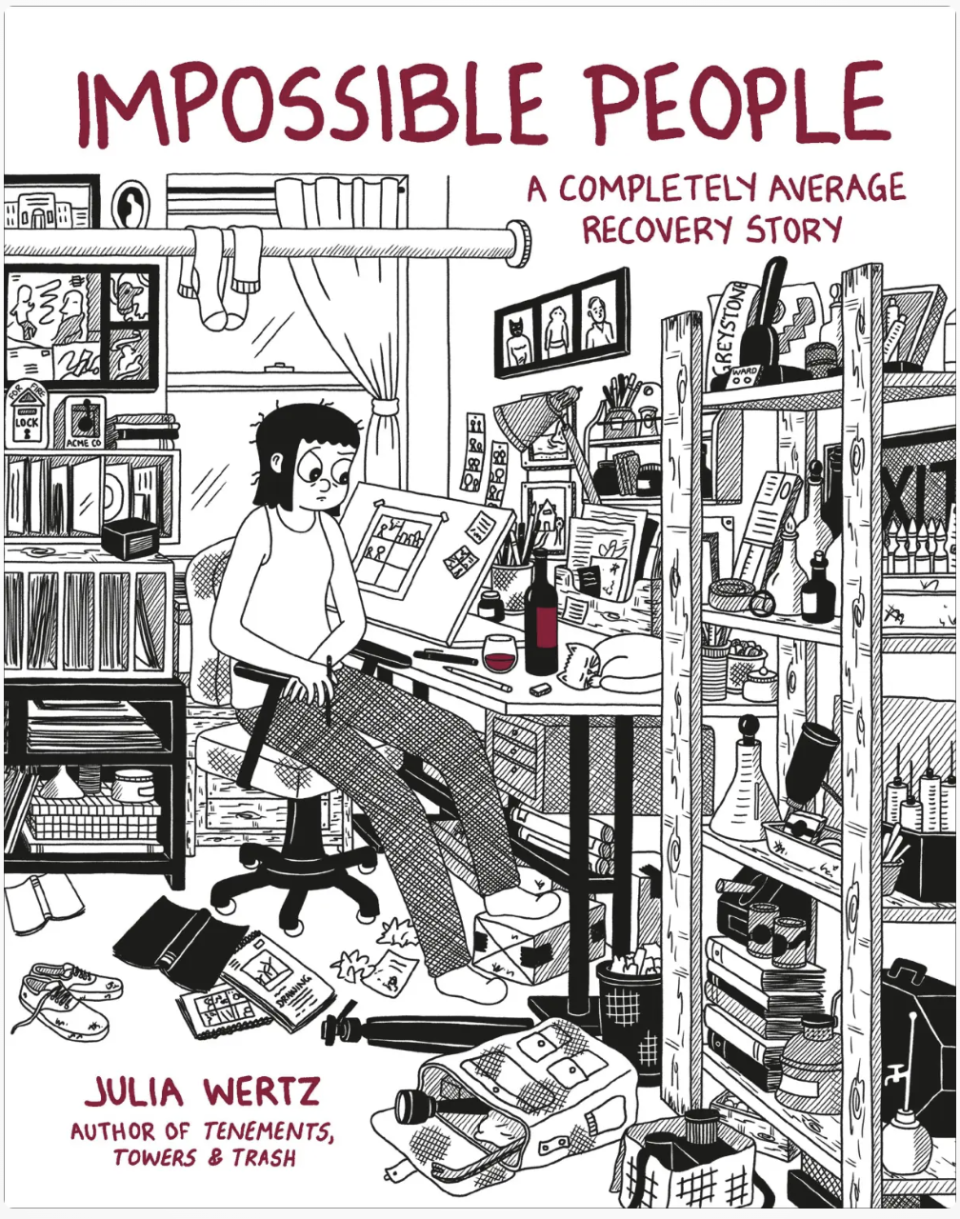

But what about after you make that commitment? What happens once treatment ends, or that 12th step is far in the rearview, and all that’s left is the long, thunderously strange process of re-inhabiting a life? Along with Baby J, I’ve been thankful for a number of recent, daring stories in popular media—among them the comedy series Single Drunk Female and cartoonist Julia Wertz’s new graphic memoir, Impossible People—that flip the expectations for recovery narratives and treat sobriety as a starting point rather than an endpoint.

Like Mulaney’s, my early sober life was a hall of fun-house mirrors, each one waiting to reveal a new, terrible reflection. During a tearful conversation with my wife on our couch in 2015, I quit drinking—and in that instant split into two warring factions of myself. There was the sober me who chose to seek help, and the drunken me who had clanged around in my life months, weeks, hours before. It didn’t make sense. Quitting was subtraction, I thought. But days felt longer without hangovers for me to sleep through, and many nights I’d dream I was drunk—the vibrant slowness of it flowing through me again, along with a familiar, potent shame.

And in the waking world, my recovery work only showed me a clearer picture of who I’d been. Getting sober of course meant repairing decades of damage, in my life and in others’. But I didn’t expect my favorite people and places to morph into living archives of my old, worst mistakes. Seeing them sent me back through time and into a corridor of regret, where I lived again through a series of drunken, horrifying moments I was desperate to distance myself from. I existed in a state of apology, or at least the constant desire to apologize, to erase the bad depiction of myself that was still, defiantly, everywhere.

And worse, there was nothing funny about it—or at least I didn’t think so until watching Single Drunk Female, which recently finished its second season on Freeform. The show follows Samantha “Sam” Fink, a culture writer who hits bottom when she drunkenly clocks her boss with a phone. Soon enough, she’s in a court-ordered recovery program in her hometown near Boston, which showrunner Simone Finch renders as a hilarious, poignant hellscape of thick accents and existential consequence. Every character and plotline brings us another mistake Sam needs to make amends for, or a puzzle box that holds a new, strange wrinkle of her sobriety: the sweet guy in her program who she can’t start a relationship with until she’s over a year sober; her ex who’s now marrying her ex-bestie; her grief over her father’s death and relationship with her surviving, wounded, narcissistic mother, played by Ally Sheedy at a perfect pitch of human chaos.

While Sam’s journey is built around her 12-step program (time passes via a daily “sobriety calculator”), the show’s real gift is showcasing what happens between those steps: the humiliations and graces of starting over, the mindfuck of sober sex, the insidiousness of “dry drunk” behavior, and learning to be the “new” you in the presence the very people who knew the old you far too well. Through two seasons, Sam stumbles her way toward understanding what took me years to realize: She’ll always be those two, warring selves. But part of recovery is learning to create the right space for each of them to somehow live within her, side by side.

That work is hard and can happen over a long, unpredictable timeline, which is a point that Julia Wertz’s Impossible People drives home brilliantly. After suspecting that she’s an alcoholic—she ends most nights getting blackout drunk in her Brooklyn apartment‚Wertz begins a years-long quest to find a recovery that works for her. Her acerbic, low-key comics have always been amusingly self-lacerating and contrarian. Here, that angle works to lower the volume on the typical addiction story. The book’s subtitle is “A Completely Average Recovery Story,” which is both a joke and a promise. There’s no debauchery. No epic meltdowns that whisk her away to rehab. (She drives herself there, calmly and with a friend.) It’s just an artist trying to understand her addiction, and how to live and create meaningfully in sobriety.

One achievement of Impossible People is that it characterizes a nonlinear road to recovery and normalizes relapses, and Wertz experiences a few. But it also tackles a slippery aspect of sobriety I’ve struggled with: social phobia. After I got sober, I withdrew from everything I’d once valued as a writer: book launches, literary readings, community. I wasn’t afraid they’d make me want to drink. I was afraid that drinking was the only way I knew how to belong there. “I feel like a person without content,” I once joked to an editor, and then grew scared about how true that joke felt.

Similarly, Wertz leans into the solitude of creating comics while sober, and my favorite stretches of Impossible People explore the heart of that drive to solitude and the threat it poses to living a full, sustainable sober life. “If someone warned me that getting sober meant I’d have to socialize with strangers, I probably wouldn’t have done it,” she jokes at one point, but Impossible People makes the case that without a proper community, sobriety can create a fear of the world so large, you forget how to live in it.

These new, sobriety-first stories aren’t perfect. Some beats opt to teach rather than explore, and most of the stories center white protagonists. Voices like Kaveh Akbar, Melissa Febos, Kiese Laymon, and Dr. Nzinga Harrison are among those working to change that, and I hope they get the chance to. More is more, and not only so those of us in recovery can see ourselves reflected in mainstream narratives. As any sober person knows, it’s not hard to find people sharing tales of their recovery and diving deep into what their stories mean. But the stories are often locked away in anonymous rooms, and for good reason. The power of Baby J, Single Drunk Female, Impossible People, and anything that comes after is that they can be shared—which helps with stigma, but is also useful to the loved ones closest to our recoveries and often among the most impacted by them.

On Saturday mornings I like to sit in bed and scroll through my favorite Instagram accounts, self-billed “sober meme influencers” who post riffs on the memes of the moment. They’re bleak, caustic, and hilarious, and I’ll tap my wife’s shoulder and hand her my phone for the best ones. I love when she laughs at them as hard as I do. Because she’s also laughing with me at the intricate, seismic, and most private moments of my recovery, and I become alive both in that moment and in our teary, awful talk on the couch eight years ago, when the subject of my drinking was far from funny.

In this one, wildly stupid way, there’s now a space where those moments can live side by side. It’s good, learning that gratitude can look like that, too.

You Might Also Like