‘When you turn it on, it’s like blowing snot at you’: How the Hammond organ revolutionised rock

We all know the sounds of the mighty Hammond organ when we hear them, from the ghostly sorrow and majesty of Procol Harum’s Whiter Shade of Pale to the bubbling glide and splash of Booker T and the MG’s Green Onions, the heavenly pillow bearing up the Beatles’ Let It Be or the bright, dirty vibrato soloing of Deep Purple’s Hush.

You still often hear its thrilling timbres on modern House dance tracks or billowing in the background of monster ballads by Adele and Lana Del Rey. The Hammond Organ was the first electronic instrument to become a mainstay of popular music, and it is still going strong 90 years since its invention.

The Hammond is “the king of the organs” according to Jeff Kazee of US rockers Southside Johnny and the Asbury Jukes. “A tone-creating, scene-stealing, singer-inspiring vibe machine.” It is “light years beyond any other electric organ,” declares Andy Burton, keyboardist with John Mayer, Cindy Lauper and Little Steven. It is a “mechanical marvel” in the words of Katy Perry’s keyboard player Ty Bailie. “It can subtly hold a song together like glue or it can scream and shout and tear holes into space and time. It’s the sound of a future we are still yet to reach.”

Patented on April 24, 1934, by mechanical engineer Laurens Hammond, the very first Model A Hammond was purchased by automobile magnate Henry Ford. First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt took delivery of the second in the White House. George Gershwin was an early adopter, and the Hammond soon turned up on recordings by Fats Waller and Count Basie. In its first two years on the market, radio stations, Hollywood studios, ice rinks, fairgrounds and cinemas all acquired the new portable wonder keyboard, along with 2,500 churches, often in black communities to whom it was marketed as a cheap substitute for expensive pipe organs.

Its rich, wild sound became embedded in gospel music, amongst the building blocks of soul. British jazz wizard James Taylor (leader of the James Taylor Quartet) believes the sound taps into a deep well of feeling, reaching back to pipe organs developed by the ancient Greeks and Romans. “The organ was the backdrop for the whole religious culture that’s gone on for the last 2,000 years. It pulls strings that are latent but deep in the human psyche.”

The Hammond conjured this with ingenious technology. “Laurens Hammond was originally a clockmaker. And if you look inside an old Hammond the tone wheels look like works of a clock spinning in front of magnets,” points out award-winning jazz organist Brian Charette. Its system is fiendishly complex, with early Hammonds containing a generator running at 1800 revs per minute, driving over 90 tiny metallic discs spinning past electromagnets creating alternating currents to make sonic tones that pass through filters controlled by the keyboard. There are two rows of 61 keys on most models, with each key pressing down on nine contacts for “drawbars” – sliders that affect frequencies and harmonics. There are up to 25 pedals, plus an “expression pedal” controlling volume and attack.

And then the signal is amplified, most famously through a Leslie speaker (a heavy rotor cabinet invented in 1937 by Donald Leslie) which contributes its own unique harmonics. The now classic Hammond B3 model (and its even larger relation the C3) arrived in 1954, a 425lb beast that needs to be regularly maintained with oil top-ups. “Being in a room with a Hammond organ and Leslie speaker, with their spinning gears, leaking oil, miles of wires, and glowing hot tubes, is a showcase of what human beings are capable of creating, through genius, capitalism and luck,” enthuses Bailie.

Jimmy Smith revolutionised Hammond playing in the 1950s, conjuring bebop basslines by pumping foot pedals, freeing his hands to riff and solo, a driving style that shifted jazz towards Rhythm and Blues. Ray Charles and James Brown used the Hammond in the development of soul and funk. Booker T. Jones infused the southern soul of Stax records backing Wilson Pickett, Otis Redding and Bill Withers, scoring breakout Hammond instrumental hit Green Onions in 1962. In the emerging blues rock scene in the UK, Georgie Fame, Ian McLagan of the Small Faces and Stevie Winwood with the Spencer Davis Group brought Hammond to the fore. Then Matthew Fisher played the spooky organ on Whiter Shade of Pale in 1967 and the floodgates opened.

“The Hammond became the supreme organ of the rock era because its big, fat, all-guns-blazing sound could compete with an electric guitar,” according to Paul McCartney’s long-serving keyboard player and musical director Paul “Wix” Wickens. There were other portable keyboards, notably the Vox Continental, Farfisa and Wurlitzer, but the Hammond had a range to beat them all. “You’ve got chorus and vibrato and nine drawbars with different harmonics, so depending on how you use them together you can get the most amazing sounds. You can knock all the bass off and be very high, bring in the middle harmonics and make it angular and angry or boost the bottom to make it round and smooth. You use a volume pedal as your emotion, that’s a big part of playing. It’s very organic, very connected to you as a player.”

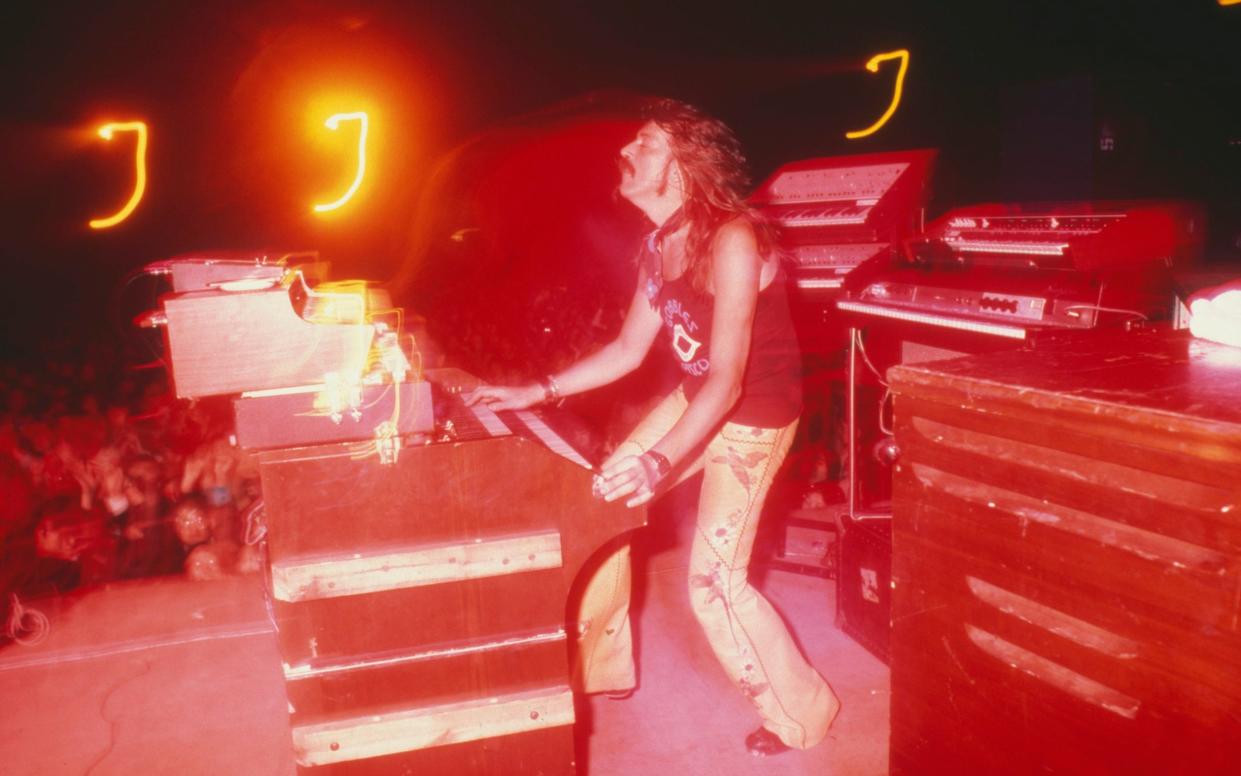

The Hammond’s versatility made it essential to progressive rock, formidably played by Keith Emerson of the Nice and Emerson, Lake & Palmer, Rick Wright of Pink Floyd and Rick Wakeman of Yes. As a counterpart to guitar soloing, the Hammond featured heavily in the Allman Brothers (played by Gregg Allman) and early Santana (by Gregg Rolie, who went on to form Journey), while Jon Lord put it front and centre of Deep Purple’s heavy riffing.

The arrival of portable synthesisers in the late 70s effectively ended the Hammond’s all-conquering reign, but it remained a firm favourite of classic rockers, as exemplified by the fantastic playing of Danny Federici with Bruce Springsteen and the E Street Band. It hung on in the influential 90’s Neo Soul of D’Angelo and has remained a staple of jazz with such influential players as Snarky Puppy’s Cory Henry. In the pop charts, British club outfit Rudimental’s breakout 2012 hit Feel the Love rides in on rich, warm Hammond chords.

“I grew up listening to Jimmy Smith and lots of blues and soul in my dad’s record collection,” explains Rudimental keyboard player Piers Aggett. “So we thought it’d be a great idea to start a Drum and Bass record with soulful organ, but actually it’s an organ patch (a virtual replica) from (digital studio programme) Logic 8. But after it became a success, we were able to buy a Hammond B3 for our studio. There’s a famous jungle rumble bass sound that is actually the Hammond pitched down electronically to capture the low timbre. You can still hear the Hammond all over pop music.”

The increasing efficacy of virtual Hammonds and Leslie emulators (several marketed by the Hammond company themselves) means that modern keyboard players can use the sounds of the instrument without carting the real thing around. But singer-songwriter and former editor of Keyboard Magazine, Jon Regen insists that nothing beats the real thing. “It is still utilised all the time, especially in live situations for the gravitas that it brings,” says Regen.

“Whenever you see a band of note, they want to have a real organ on stage. It’s the majestic nature of it: when you turn it on, it’s like blowing snot at you and crackling. I think the humanity and the imperfections make it the antidote to all the shit in pop music today, because it feels real in a world where so much doesn’t. You want to be near it, to feel that sound. That, to me, is why it will never go away.”

Benmont Tench of Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers is one of the pre-eminent Hammond players in rock history (“He’s the king of Hammond,” according to Regen). Tench first played one in a studio in Tulsa in 1974 and never looked back, adding his dextrous talents to recordings by Bob Dylan, Stevie Nicks, Johnny Cash, Roy Orbison, Aretha Franklin, Neil Diamond, Alanis Morisette, U2, The Who and The Rolling Stones (on their latest album, Hackney Diamonds). “It’s a paintbox, is what it is,” says Tench.

“Palette knife-like rough textures, Pollack spatters, fine glazes, blurry watercolours, stark chiaroscuro. John Allair’s sweet work with Van Morrison, Matthew Fisher with Procol Harum, Booker T, Al Kooper with Bob (Dylan), Mac with the Faces, Neil Larsen with Leonard Cohen, Jon Lord with Deep Purple, mighty Billy Preston — all this from one glorious block of wood, metal, wire, ceramic and plastic, and from an alarm clock company no less. Give me my C3 and Leslie, turn up the spring reverb just a little, add a stompbox or two, grab the drawbars, lean back and hold on for dear life!”

With thanks to Jon Regen. For further reading: The Hammond Organ: Beauty in the B by Mark Vail (Backbeat Books)