What’s Going On, 50 years on: The bitter true story of Marvin Gaye’s iconic album

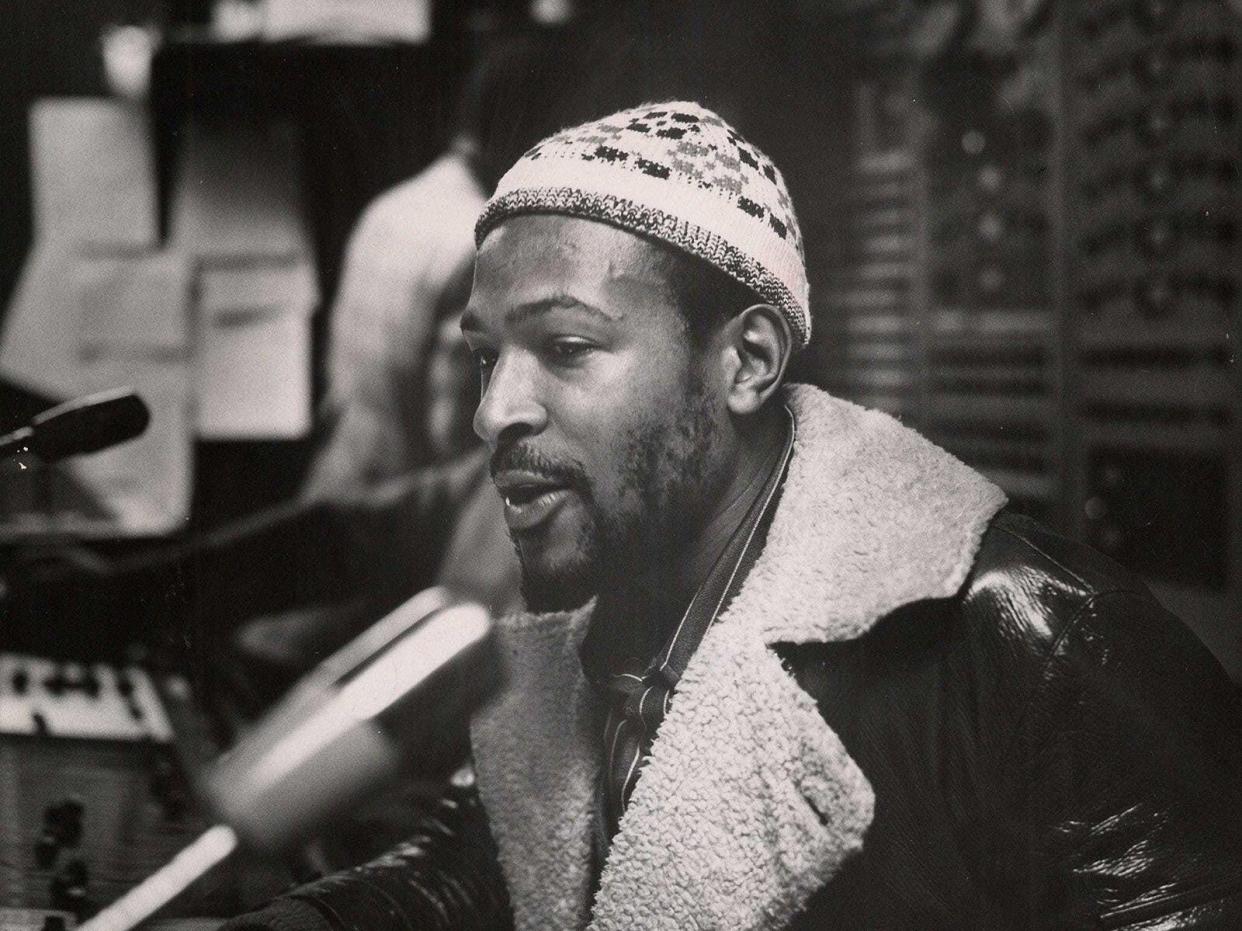

Marvin Gaye photographed by Gordon Staples, concertmaster of the Detroit Symphony Orchestra, in the Motown studio console room in early 1971

(Alamy Stock Photo)Put it out or I’ll never record for you again” was Marvin Gaye’s stark warning to Berry Gordy, after the founder of Motown Records refused to release the single “What’s Going On” in the summer of 1970.

Berry – who was Gaye’s brother-in-law at the time – told almost anyone who would listen that he detested Gaye’s protest song, which he thought was too long, too formless and not commercial enough to be played on radio, a prerequisite for the scores of No 1 songs he’d crafted at his Detroit studio known as Hitsville USA. Gordy was even quoted as describing “What’s Going On” as “the worst record I ever heard in my life”.

In his memoir Smokey: Inside My Life, soul legend Smokey Robinson recalled telling Gordy he thought Gaye’s track was “brilliant”. The Motown boss was sure he would talk Gaye out of it. “That’s like trying to talk a bear out of s***tin’ in the woods,” Robinson replied. “Marvin ain’t budging.”

Gaye held firm during a seven-month power struggle that eventually concluded with the hit single becoming the centrepiece of the ground-breaking album What’s Going On, which explored the issues of poverty, racial discrimination, environmental destruction, urban decay, police brutality, drug abuse, political corruption and the devastating effects of the Vietnam War. David Van DePitte, the album’s arranger, later revealed that Gordy thought Gaye “was absolutely insane” to want to feature social commentary on a record “that was going to be the biggest fiasco that ever was”.

What’s Going On is now widely recognised as one of the most important musical works of the 20th century, a song cycle that gave Black artists a licence to push the musical and political boundaries of their art. In November 2020, Robinson told USA Today that this “profound” masterpiece was perhaps the greatest album of all time, one that is “even more poignant” in the era of Black Lives Matter than it was when released on 21 May 1971.

Gordy might even have won the battle of wills had it not been for Harry Balk, Motown’s no-nonsense head of A&R, who had once notoriously thrown a tax officer down the stairs of the label’s Detroit headquarters during a row over an audit. Balk, who was 91 when he died in 2016, told Detroit News that he received a demo 45rpm pressing of “What’s Going On” by mistake. “This Marvin Gaye acetate was mixed in with a stack of other records and just fell on the floor. I loved it, and made a tape of it before sending the acetate on. I listened to it over and over, and fell more in love with it. I started playing it for people who came into my office. Of course, now everybody will tell you how wonderful they thought “What’s Going On” was, but I played it for the hot producers and got nothing but negative opinions. The only one that was really knocked out with it – the only one – was Stevie Wonder.”

Balk repeatedly tried to convince Gordy of the song’s merits, but the Motown boss criticised its jazz influences. “Ah, that Dizzy Gillespie stuff in the middle, that scatting, it’s old,” Gordy told Balk. Undeterred, seizing an opportunity while Gordy was away travelling, Balk went to Barney Ales, vice president of sales, and told him that unless they released “What’s Going On”, they would have nothing new to release from Gaye, a performer who’d made the company millions of dollars with hits such as “I Heard It Through the Grapevine” and “Too Busy Thinking About My Baby”.

Without Gordy’s knowledge, Ales commissioned a pressing of the 100,000 copies of “What’s Going On”, and the single was sent out to radio stations on 17 January 1971. Within four days, after enthusiastic plays from DJs across America, every single copy had sold out. It would go on to sell two million copies, hailed by Jackson Browne as “the most articulate and deeply felt anti-war song of the time”.

The inspiration for “What’s Going On” came from Four Tops singer Renaldo “Obie” Benson, after seeing an incident of police brutality in San Francisco. In May 1969, during a tour of California, the band were stuck in a traffic jam when they saw young protestors at People’s Park being savagely attacked by cops in riot gear. “The police was beatin’ on them, but they weren’t bothering anybody,” Benson told Ben Edmonds for the book What’s Going On: Marvin Gaye and the Last Days of the Motown Sound. “I started wondering what the f*** was going on. What is happening here? One question leads to another. Why are they sending kids so far away from their families overseas? Why are they attacking their own children in the streets here?”

Benson and fellow Motown writer Al Cleveland shaped a tune about the violence, but it was rejected by Benson’s fellow Four Tops bandmates as being “too political”. Joan Baez also turned down the song before Benson offered it to Gaye. The Washington-born singer, who was 31 at the time, said he wanted to add his own input and Benson agreed. “Marvin definitely put the finishing touches on it,” Benson explained. “He added lyrics, and he added some spice to the melody. He added some things that were more ghetto, more natural, which made it seem more like a story than a song. He made it visual. He absorbed himself to the extent that when you heard the song you could see the people and feel the hurt and pain. We measured him for the suit, and he tailored it.”

One of the key changes that Gaye made to the song was to remove the question mark that Benson had originally fixed to the track. Gaye was adamant that the song was a statement rather than a question. Gaye was becoming more politicised and wanted to respond creatively to a tumultuous period in American history. “For the first time I really felt like I had something to say,” he commented.

One of his rows with Gordy over a change in musical direction came when the Motown boss was on holiday. “I was in the Bahamas trying to relax,” Gordy recalled in the 2016 documentary Marvin, What’s Going On? “He called and said, ‘Look, I’ve got these songs.’ When he told me they were protest songs, I said, ‘Marvin, why do you want to ruin your career?’” After the success of the single, however, Gordy realised that it was in Motown’s interest to capitalise on the sales and release a whole album of Gaye’s new songs. He realised he’d antagonised Gaye and devised a way to entice him to record the album: he bet Gaye that he could not deliver an album in just 30 days. Neither men ever disclosed the amount they wagered.

The core inspiration for the protest songs came from Gaye’s personal life. His younger brother Frankie Gaye had been stationed in Vietnam, working as a radio operator. The pair had an uneasy relationship and Frankie felt let down by the lack of contact from his famous brother while he was facing carnage nearly 9,000 miles away. “The death and destruction I saw in Vietnam sickened me,” Frankie told Gaye’s biographer David Ritz. “The war seemed useless, wrong and unjust. I relayed all this to Marvin and forgave him for never writing to me while I was over there. That had hurt, because he was a big star and none of my buddies believed he was my brother. ‘Wait,’ I told them, ‘He’s going to write me back and prove it to you.’ He never did.”

Gaye tried to put himself in Frankie’s shoes by writing the song “What’s Happening Brother”, about the disillusionment of war veterans returning to President Richard Nixon’s America, a country in which unemployment was running at six per cent in 1971. Frankie said the song was “so personal and heartfelt” that he wept after hearing it for the first time.

Gaye was in poor shape mentally during the making of What’s Going On. His marriage to Anna Gordy was coming apart at the seams and he was still grieving for his singing partner Tammi Terrell – with whom he’d recorded classics such as “Ain’t No Mountain High Enough” – who had died of brain cancer in March 1970, when she was just 24. “Marvin was depressed just before What’s Going On,” the singer’s American football star friend Mel Farr said. “He’d been holed up in his house for a long time.” Gaye was taking increasing amounts of hard drugs. He was traumatised by the daily news, especially the killing of four young students by the National Guard at Kent State University two months after Terrell’s death. “I couldn’t sleep, couldn’t stop crying,” he told Ritz in Divided Soul: The Life of Marvin Gaye. In his one interview in the summer of 1971, with Disc and Music Echo magazine’s Phil Symes, Gaye admitted “I was terribly disillusioned with life in general.”

He channelled all that despair and anxiety into What’s Going On, which began recording on 17 March 1971. He brought in Farr and his Detroit Lions colleague Lem Barney to be part of the vocal chatter that launches the title track. The LP, which subverted every aspect of the Motown template of carefully crafted love songs and ballads, went on to become the label’s biggest-selling album of all time. “The entire What’s Going On album, from start to finish, is a masterpiece,” Bruce Springsteen told BBC’s Desert Island Discs. “It was sultry and sexual while at the same time dealing with street-level politics. That had a big influence on me. Along with the idea that it was a concept record without being cursed by that name. It was a record that had a thread you can follow from the first song to the last and it created a world that you could walk into and then come back out of.”

Although Gaye, who said that all the inspiration for the album “came from God Himself”, won his bet with Gordy – the album was completed in under 30 days – there has been plenty of mythologising about the recording sessions, during which Gaye supposedly worked constant 16-hour days to cut the nine tracks: “What’s Going On”, “What’s Happening Brother”, “Flyin’ High (In the Friendly Sky)”, “Save the Children”, “God is Love”, “Mercy Mercy Me (The Ecology)”, “Right On”, “Wholy Holy”, and “Inner City Blues (Make Me Wanna Holler)”.

The sessions at both Hitsville and Golden World Record studios were, in truth, chaotic, often not starting until midnight. “It was a prolonged process because Marvin didn’t turn up half the time. He would have an afternoon or evening appointment and he’d not show,” said Van DePitte, who admitted to Billboard that he had been warned the singer would be “a pain in the fanny”. According to music journalist Dorian Lynskey, in his book 33 Revolutions Per Minute: A History of Protest Songs, “Gaye kept joints and scotch on hand for the coterie of friends that attended the sessions, and masturbated at length before vocal takes in order to drain himself of carnal distraction.”

At the end of a month of recording dates, Gaye took some of the master tapes with him when he flew from Detroit to Sylmar, California, to play the role of a biker called Jim in Chrome and Hot Leather, a movie about a young Green Beret. “He didn’t talk about his music much,” said cinematographer John Toll. “We just knew him as a lanky, friendly guy who asked a lot of questions about the process. We talked a lot about football too. He became one of us.”

Although Gaye tinkered with the mixing of the songs up to the point of final production, he conceded that Van DePitte had helped fulfil his vision, orchestrating versions of Gaye’s inventive words and melodies in a skilful blend of jazz and soul musicians, the Detroit Symphony Orchestra and Gaye’s smooth, soulful voice. “Marvin couldn’t read or write music per se. He needed not only a musical secretary, but somebody who knew how to organise the stuff and get it down on tape,” Van DePitte said. The arranger brought in the brilliant drummer Chet Forest and saxophonists Eli Fountain and Wild Bill Moore, as well as suggesting the musical bridges between the tracks as way of helping Gaye’s “little stories” flow into one another. Although Gaye was pleased with the results, he was miffed about the praise for Van DePitte’s orchestration. “I’m gonna learn to write music,” Gaye said in the liner notes for the album. “Why? Because I want all the credit.”

One of the stand-out tracks was “Mercy Mercy Me (The Ecology)”, written solely by Gaye, which lamented the ecological nightmare of “oil wasted on the ocean and upon our seas, fish full of mercury and radiation underground and in the sky”. The song was performed by musicians Ledisi, Grace Potter and PJ Morton at the 2021 Grammy awards ceremony, evidence that this prophetic anthem about environmental pollution resonates half a century later. Moore who’d played with jazz maestro Slim Gaillard in the 1940s, improvised the sweet tenor saxophone solo on the track, while backing band The Funk Brothers, especially bassist James Jamerson, laid down a sizzling groove.

“Inner City Blues (Make Me Wanna Holler)” joined “What’s Going On” and “Mercy Mercy Me” as the singles issued from the album. In his liner notes, Gaye included the credit: “Thanks too to James Nyx, a gentleman and a scholar (which I’m apparently not)”, in tribute to a songwriter who also worked as a janitor and elevator operator at Motown’s offices. Gaye wrote the melody for “Inner City Blues” and Nyx came up with the lyrics about the “have-nots” of America after seeing a newspaper headline about the “inner city” of Detroit. “I said, ‘Damn, that’s it. Inner City Blues.” In his eighties, Nyx earned handsome royalties from the numerous times his words were sampled on rap and R&B records.

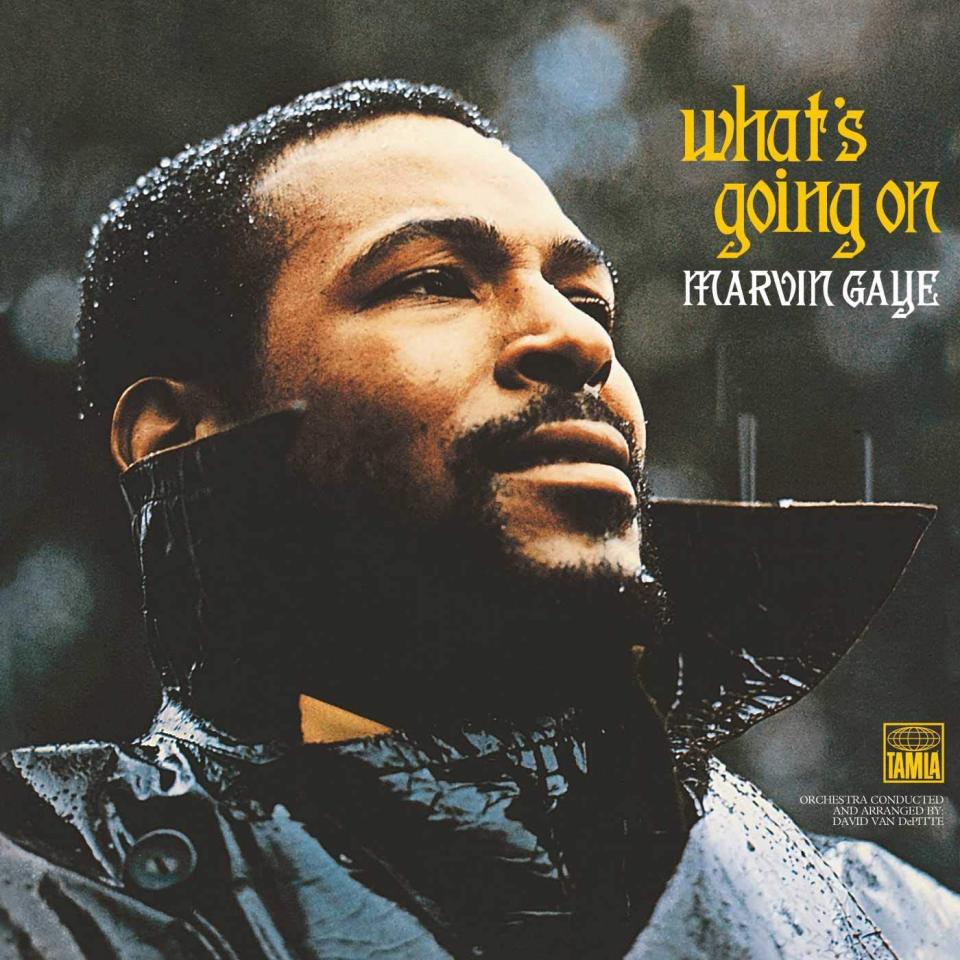

Art director Curtis McNair explained the care that went into the album cover. “I could see how emotional Marvin was in terms of the essence of the album, and I wanted to match that,” he told Boston newspaper The Bay State Banner in 2008. “We had 100 slides of photographs from Jim Hendin and I picked this one when the sleet made his hair turn white, and on top of that you have the moisture on his trench coat and that wonderful expression on his face. I thought all of that added to the drama.”

Hendin took the portrait at the singer’s Detroit home on Outer Drive. “Marvin couldn’t have been more cooperative. Marvin went out into his backyard, and as I clicked away, it began to snow. The drizzle added everything to the shots. Luck, or something stronger, was with us that day,” said the photographer. McNair’s supervisor Tom Schlesinger initially rejected the cover shot – for the “ridiculous” reason, in McNair’s words, that you could see too far up Gaye’s nostrils – until McNair demanded that Gaye had the final say. “That’s it. This is definitely the cover right here,” insisted the singer.

The album made millions of dollars, but the financial rewards did little to help Gaye escape his demons. Gaye, along with his wife Anna and Elgie Stover, wrote about drugs in the magnificent song “Flying High (In the Friendly Sky)”, and his addiction problems only increased after 1971. Gaye’s second wife Jan, the 17-year-old daughter of Slim Gaillard, met the singer, then 34, during the making of 1973’s Let’s Get It On. She experienced some of his most appalling behaviour. She said Gaye’s moods grew ever more erratic and violent as he began regularly “freebasing cocaine”. One day, high on psychedelic mushrooms and cocaine, he attacked her. “He took a kitchen knife and put it to my throat,” she recalled in her 2017 memoir After the Dance: My Life with Marvin Gaye. “I was petrified, paralysed. I thought it was all over.”

Gaye saw his own downfall as somehow fated. He remembered his mother Alberta’s melancholy warning about fame – “first ripe, first rotten” – as his life slowly crumbled in the late 1970s and early 1980s, even with the global success of his hit single “Sexual Healing”. Frequently high, he became increasingly paranoid and even suicidal. There were divorces, bankruptcy and continuing emotional turmoil with his parents. It all seemed so far from the moment he told Disc and Music Echo that he had made What’s Going On “not only to help humanity but to help me as well, and I think it has. It’s given me a certain amount of peace.”

The peace did not last, of course, least of all with his own father. Despite the fact that Marvin Sr, a minister of a Pentecostal church, had beaten Gaye on an almost daily basis throughout his childhood, the singer paid tribute to him in the liner notes for What’s Going On, declaring: “While I’ve got you reading, I’d like to first give thanks to my parents, The Rev & Mrs Marvin P Gay, Sr, for conceiving, having and loving me.” There now seems a dreadful sense of foreshadowing when Gaye sang “father, father/We don’t need to escalate” on the seminal title track. The violence between the pair spiralled out of control on 1 April 1984, a day before Gaye’s 45th birthday, when the 70-year-old killed the singer with three gunshots to the chest, following a physical altercation about a missing insurance company letter.

Marvin Sr was handed a suspended sentence and lived out his final days in a nursing home, dying in 1998. His son’s legacy lives on, especially that 1971 masterpiece. What’s Going On moved to the very top of the revised edition of Rolling Stone’s “500 Greatest Albums of All Time” list in late 2020. Yet it remains a bitter, grim irony that Gaye, whose sublime What’s Going On stands as such a clarion call against the senselessness of violence, met such a brutal end.

Read More

State of independence: Why the ‘indie’ artists you love are not as DIY as you think