Gérard Depardieu's sordid, troubling past is finally catching up with him

Before Gérard Depardieu was anybody, he was a teenage rent boy and petty thief who robbed fresh graves to steal jewellery and shoes. He lifted the lid on this appalling childhood in his autobiography, That’s the Way it Was, published in 2014, which made his upbringing in the town of Châteauroux in Central France sound like the early chapters of an Émile Zola novel.

“I've known since I was very young that I please homosexuals,” Depardieu explained in the book. “I would ask them for money.” As he got older, he got more violent.

“At 20, the thug in me was alive and kicking. I would rip some of them off. I would beat up some bloke and leave with all his money.”

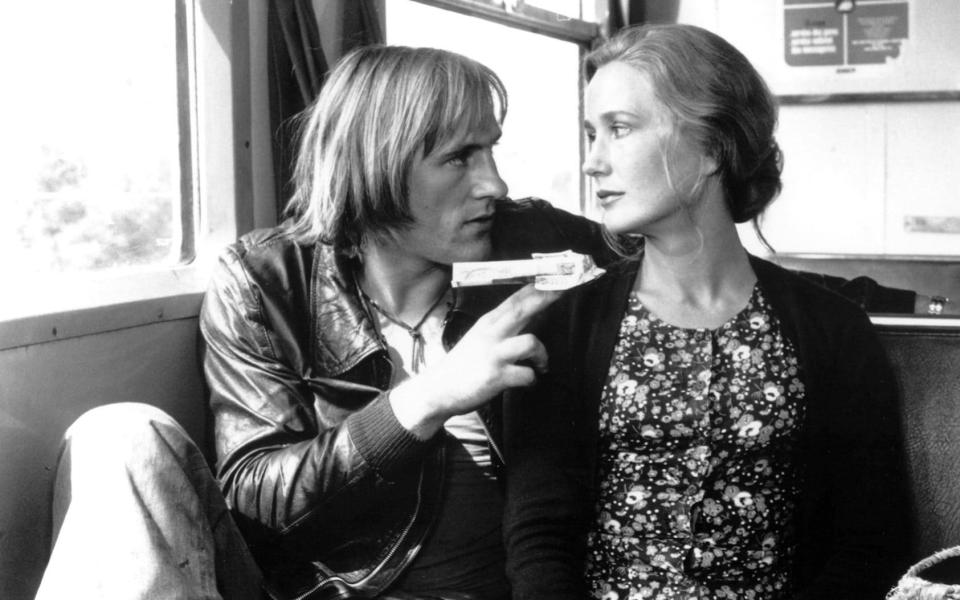

Depardieu’s ascent from these sordid beginnings to become France’s most important male movie star of the 1980s and 1990s began after he gained some notoriety on the Parisian comic stage. His breakthrough in film came at age 25, in Bertrand Blier’s bawdy comedy-drama Les valseuses (1974). He played a ruffian who steals cars, kidnaps young women and deflowers a runaway virgin – not a million miles removed from the real-life Depardieu he would later describe.

In a 1978 interview with Film Comment magazine, after he’d become internationally known in the likes of Bertolucci’s 1900 (1976) and Barbet Schroeder’s Maîtresse (1976), Depardieu made a fateful remark which has come back to haunt his career repeatedly since, and feels especially queasy-making now.

“I had plenty of rapes, too many to count,” he told the interviewer about his rough adolescence.

In itself, that quotation read ambiguously about whether he was the perpetrator, the victim, or both. An interviewer for Time magazine raised the question in January 1990, when Depardieu was in the running for the Best Actor Oscar for his lauded turn in Cyrano de Bergerac. Asked specifically whether he had been a participant in those rapes, Depardieu replied, “Yes. But it was absolutely normal in those circumstances. That was part of my childhood.”

Unsurprisingly, this follow-up interview prompted an outcry from women’s rights activists, while in France, it was widely blamed for Depardieu losing the Oscar. In the Washington Post, the columnist Judy Mann urged a boycott of his films, in a column with the headline “How Do We Handle the Rapist-Turned-Heartthrob?”

Depardieu denied admitting to rape in the Time interview, claiming that he was mistranslated, and threatened a libel suit against the magazine and any other publication that would reprint the wording. In a statement, he said “It is perhaps accurate to say that I had sexual experiences at an early age. But rape – never. I respect women too much.” Time refused to retract the passage as published.

The atrocious reaction to the scandal in France showed just how different the country’s cultural norms surrounding consent are to those in the US. Depardieu’s defenders kept reverting to the kind of blind hero-worship and other coddling tactics that let high-profile sexual aggressors off the hook.

When the writer Marguerite Duras, who four times directed him in films, was asked about Depardieu’s comments, she waved them away, saying, “When I was 8½, I stole an apple from the garden.” The culture minister Jack Lang called the whole affair “a low blow against one of our great actors”, while Jacques Attali, an adviser to then-president François Mitterand, lambasted it as “a vile defamation with a high financial payout.”

Duras died back in 1996, but one wonders if Lang, Attali and their ilk will be back for another round of moral support, now that Depardieu has been charged with raping a 22-year-old actress three years ago at his Paris home.

The assault was reported in 2018 and passed on to prosecutors, but charges were dropped after an initial nine-month investigation. When Depardieu’s accuser refiled her accusation in October, the authorities this time found enough evidence to proceed. He continues to deny all culpability.

Depardieu’s glory days as a star seem far enough behind him now that the likelihood of the industry rallying to his support, even given the notorious French history of rape apologism, is much less assured than it once was. Some kind of “wild oats” defence certainly isn’t one within ready grasp these days for a septuagenarian former megastar.

Depardieu’s prolific career has seen him nominated for the Best Actor César a Streepian 17 times, winning twice, in 1981 and 1991. He became a French national treasure around the time of Jean de Florette (1986), and continued to work with many of the country’s most important filmmakers, including François Truffaut (The Last Metro; The Woman Next Door), Jean-Luc Godard (Hélas pour moi) and Maurice Pialat (Loulou; Police; Under the Sun of Satan).

The Oscar nomination, and his Hollywood success in Peter Weir’s Green Card (1990), led to a brief spree of English-language parts, whether as imaginary friends (Bogus), dastardly furriers (102 Dalmatians) or portly musketeers (The Man in the Iron Mask). He was a dashing Christopher Columbus for Ridley Scott in the epic flop 1492 (1992).

Even when he became greatly in demand, Depardieu didn’t particularly clean up his act. Blier, with whom he worked eight times, explained of one shoot, “We literally had to follow him at night to stop him getting into punch-ups. He would deliberately go into the most dangerous areas, looking for trouble. Even now when he arrives at the door, I think, ‘Christ, where are the valuables?'”

Depardieu’s record with the law is already chequered, to say the least. He’s been arrested for drink driving numerous times – most recently last August – and was fined €4,000 in 2013 for falling off his scooter with a blood alcohol level nearly three times the legal limit. He has bragged about being capable of knocking back 14 bottles of wine in a standard day, often beginning before 10am – and this after a quintuple heart bypass in 2000.

He was also escorted off a flight to Dublin in 2011, for publicly urinating in the cabin before take-off, in a state that fellow passengers regarded as clearly drunken. “[I’m] drunk sometimes, but my drunkenness is part of my excess,” he has said. “I think it corresponds to an image that the French love. Someone who is a bit of a rebel, who shakes things up, and is sometimes drunk.”

It’s that rebellious image which, he’s convinced, endears him to Vladimir Putin. In 2012, Depardieu moved to Belgium as a tax exile, to escape the 75 per cent “supertax” which then-President François Hollande was imposing on the super-rich in France. Straightaway, Putin granted him Russian citizenship, which he gladly accepted.

He says the reason he gets along with Putin so well is that “we could both have ended up as hoodlums”. There are memes online of them rubbing noses. Meanwhile, Depardieu’s denial of Ukraine’s independence – “I love Russia and Ukraine, which is part of Russia” – led to him being blacklisted by the country’s Ministry of Culture in 2015.

In his autobiography, Depardieu revealed his guilt over becoming estranged from his son Guillaume, eldest of four, who went off the rails in his teens and was labelled an enfant terrible by the French press. By his early twenties, Guillaume had spent two spells in prison for heroin dealing and theft.

He would manage to win a César as most promising newcomer in 1996, but like his father, he admitted to working as a rent boy when broke. He also had a bad habit of driving scooters while intoxicated, and had a leg amputated after an accident in 2003. His health compromised by those surgeries and further drug use, he died of pneumonia in 2008, aged just 37.

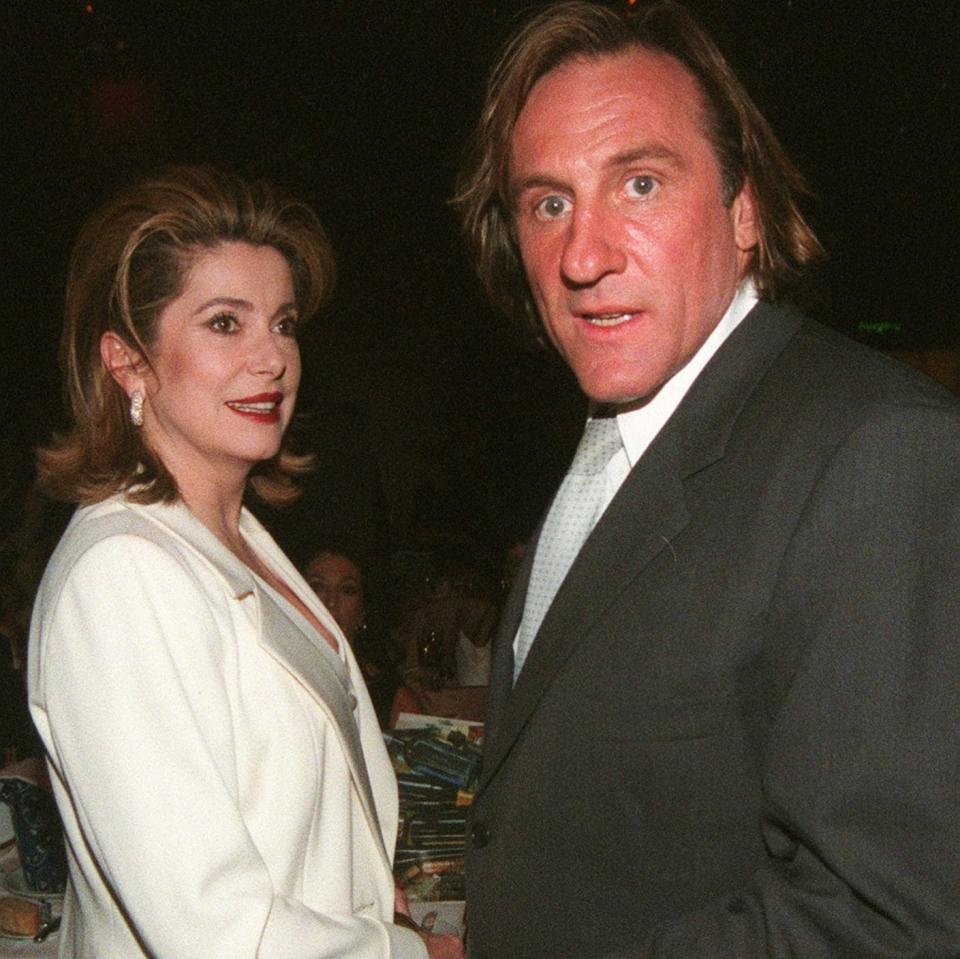

French journalists, in the wake of this rape charge, will be clamouring to know what Depardieu’s frequent co-star Catherine Deneuve has to say about it all. They’ve made nine films together and have often been associated as friends. She wrote an open letter defending his right to move to Belgium amid heavy criticism in 2012, even if she later expressed reservations.

But Deneuve has also been at the forefront of an anti-#MeToo movement in France, putting her name to a 2018 open letter which suggested that a “witch-hunt” in the wake of the Harvey Weinstein case amounted to a puritanical assault on sexual freedoms.

“Rape is a crime,” the letter began. “But trying to seduce someone, even persistently or cack-handedly, is not – nor is men being gentlemanly a macho attack.”

It’s the kind of mitigating argument which gave the Weinsteins a grey area to operate within the whole time they were active, and until now, has managed to protect the likes of Depardieu.

As the industry’s golden child for so many years, his unapologetic debauchery has been tolerated and even indulged. This feels like the moment when excuses just dried up.