The forgotten Swede who made the Grand Canyon famous

In mid-afternoon at the South Rim, it was hard to believe that Americans once had to be encouraged to visit the Grand Canyon. Daytrippers, fresh off the train after a two-hour journey from Williams, pouted at the end of selfie sticks; hikers sweated the last yards up the Bright Angel Trail; diners in the El Tovar Hotel gazed through the windows over the crumbs of their club sandwiches; and browsers in the gift shop dithered over the Grand Canyon thirstystone coasters, the Grand Canyon prickly pear taffy, and the beige cotton Grand Canyon National Park bandana, complete with topographic map of the Colorado River, that carver of the chasm.

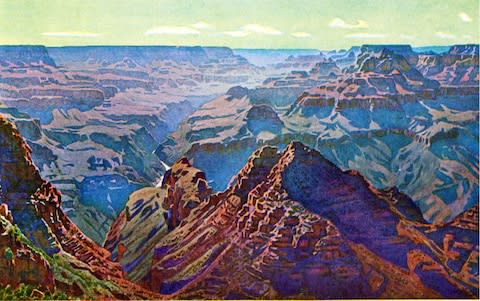

A few browsers, this one included, paused by a postcard stand, where offerings included reproductions of two watercolours. Even at seven inches by five, they were impressive: images of near-photographic detail, subtly balancing light and shade and conveying a powerful sense of the canyon’s depth. I didn’t need to turn to the back to see that they were by Gunnar Widforss. He had brought me to Arizona, just as, in the Twenties and Thirties, he brought thousands of others.

It is exactly a century since the Grand Canyon was designated a national park – on Feb 26 1919, three years after the creation of the National Park Service itself, under the directorship of Stephen Mather, businessman, outdoorsman and born promoter. It was Mather who set Widforss on his way to becoming “the painter of the national parks”.

Widforss was making a reputation but not much of a living by the age of 41, when he left his native Stockholm in December 1920 intending to travel via the United States to Japan. By the time he reached Los Angeles, he was short of cash, so he did what he had long done in Europe: he found scenic places busy with tourists where he could sell his landscape paintings.

By March 1921 he had reached Yosemite Valley in California, where he bumped into Mather one morning. Mather needed someone to show Americans what there was worth seeing and saving in their country’s newly protected places; Widforss needed work. Over the next decade, the Swede (who would become a US citizen in 1929) painted pretty much all the national parks in the West. His paintings were everywhere – from railroad company brochures to the galleries of the Smithsonian Museum in Washington DC.

No landscape gripped him as the canyon did. He wasn’t the first notable artist to paint it (Thomas Moran and William Holmes preceded him), but he was alone in making the place his home; in giving his address as “Grand Canyon”.

And yet, less than a century on, though the North Rim has a Widforss Trail and a Widforss Point, the man himself is forgotten. Well, not quite. He has two notable champions. One is a fellow Swede, Fredrik Sjoberg, who with his 2016 book The Art of Flight has paid entertaining tribute to Widforss’s role in that great American project, as he puts it, to place “virgin reserves... here and there throughout the country, like Sundays in a landscape of weekdays”.

The other champion is Alan Petersen, curator of fine arts at the Museum of Northern Arizona in Flagstaff, a silver-haired, silver-bearded man of 63 with the lean frame of a regular cyclist. In 2009, he organised the first Widforss exhibition in 40 years. He is cataloguing the artist’s works (currently more than 1,200) and planning – when he gets a break from teaching – to write a biography. When we met in Flagstaff, one of the tourist gateways to the canyon, he told me: “My mission over the past 10 years has been to get Gunnar greater recognition.”

Thanks to Sjoberg’s book and Petersen’s writing, I was well acquainted with the Widforss story. How he had been born in 1879 as Gunnar Mauritz Widforss, one of 13 children whose father Mauritz was a shopkeeper dealing in guns and hunting clothes and whose mother was an amateur painter. (The shop, incidentally, was bought in 1968 by the womenswear chain Hennes, which renamed itself Hennes & Mauritz – now better known as H&M – and added men and children to its customer base.) How, when he fetched up at the Grand Canyon, he traded paintings with the company running the El Tovar Hotel (one hangs in the lobby still) for a room in a staff dormitory and meals at Bright Angel Lodge. And how, having been warned by a doctor that he shouldn’t be working at altitude, he resolved to wrench himself away from the canyon and his friends and, on the drive to bid them goodbye, had a heart attack. He died on Nov 30 1934, aged 55.

Until I arrived in Flagstaff, though, and joined Petersen in an archive room at the museum, everything I had seen of Widforss’s work had been a reproduction. But here were nearly 20 paintings, mostly of the canyon but also including depictions of a park in Colorado and cypress trees in Monterey in California. There was a thrill in seeing the luminous layers of his watercolours on an original.

New to me, too, was the story of how Petersen’s and Widforss’s careers had become entwined. Petersen grew up in San Diego in California. Intent as a student on one path, he bought his mother a book about Widforss as a present in 1976; he was so taken with the man’s work that he decided his own future lay in art rather than architecture. Like Widforss, he had spent a lot of time at the canyon, doing everything from waiting on tables at El Tovar to guiding rafters down the river (“beautiful – but with moments of terror”).

He has plans to print every canyon painting Widforss made and to walk the rim marking the GPS co-ordinates of each viewpoint in order to create a map. Until he finds time, Widforss pilgrims have to make their own way. I’d recommend a request to see the Grand Canyon Museum Collection on the South Rim, which, in addition to more Widforss originals, has an extraordinary assembly of artefacts – from the pocket watch of John Wesley Powell, explorer of the canyon, to the remains of a ground sloth from the Pleistocene period.

My own visit to the South Rim began where Widforss’s ended: at the Pioneer Cemetery, where he lies in the shade of ponderosa pines. Beside a miniature Swedish flag, planted recently by Petersen, stood three paintbrushes left by other visitors. Behind them, a plaque set into a boulder was inscribed with lines by Robert Browning: “Here, here’s his place, where meteors shoot, clouds form,/Lightnings are loosened,/Stars come and go!”

Also in the cemetery are the Kolb brothers, Ellsworth and Emery, who became famous for their photographs of tourists on mule rides (including Theodore Roosevelt and Albert Einstein) and for a film they made while running the Colorado River in 1911. Occasionally the Kolbs would offer Widforss a room – but then they had plenty of them: between 1904 and 1976, their rim-side seat at the canyon, which had started as a modest studio, grew into a five-storey, 23-room building complete with bedrooms, bathroom, basement and theatre. Walking around it with Dave Lewis, a cheery park volunteer, and Kim Besom, who looks after archives (and has a Widforss as her screensaver), was like touring a Tardis.

Dave entertained us with stories of the Kolbs’ run-ins with both competitors and the National Park Service, which wanted to demolish the house before it was listed as historic. Now restored, it serves as a bookshop and a gallery, where, between September and January, the work of participants in the annual Grand Canyon Celebration of Art is exhibited. I saw only an occasional watercolour among the oils, but there were one or two works in which tourists appeared, just as they tend to do most days on the edges of the real canyon.

Tourists are fewer at the North Rim, which is only 10 miles from the South as the condor flies, but some 215 miles (close to five hours) by road. Facilities and viewpoints are also fewer, though, so the tourists tend to cluster. One honeypot is the Grand Canyon Lodge, a rustic secular cathedral with soaring ceiling, where both a restaurant and a terrace offer canyon views. At sundown on the latter, a modern-day Widforss would struggle to find a pitch for a monopod, let alone an easel.

After sunrise (more elbow room, less chatter) I was delighted to see on the breakfast menu a Widforss Egg White Omelet [sic]: egg, spinach, tomato and cheddar jack cheese, served with fresh fruit and whole-grain toast. Just the thing to set me up for the 10-mile round trip on the Widforss Trail.

First, though, at 11.30am, I had an appointment with a tribute artist. At one of the North Rim’s viewpoints, a ranger, Kim Girard, had swapped her usual hat for a trilby and pulled on over her working clothes an approximation of what “Weedy” Widforss – he was 5ft 4in tall – would have worn: baggy flannel shirt, tie, glasses and gaiters. On the rim wall she rested an easel with a reproduction of a Widforss painting she was “finishing off”; behind, it, on a bigger board, she had photographs of him and his family and more examples of his work. In a presentation designed to appeal to both children and adults, she gave a brief run-through of his life and his association with the canyon and reminded them that they could walk a trail named in his honour.

She kindly dropped me off later at the start of that trail, which follows the canyon rim, then winds though a forest of fir, spruce and aspen – where the artist loved to paint – before emerging at another canyon overlook, now signposted “Widforss Point”. The first section is covered by a park-service leaflet taking in some of the most striking features, among them a viewpoint through the trees and over the canyon to the San Francisco Peaks, some 70 miles away, near Flagstaff.

I was lucky to be on the trail in mid-September, when the aspens were on the turn. Lean silver trunks were lampstands for brilliant yellow leaves, which seemed not so much to be lit by the sun as to be glowing from within.

On the return, I paused again at the viewpoint towards the peaks. I had the strange sensation that I was looking not at the Grand Canyon but at a Widforss painting made real: coppery-coloured pyramidal formations in front, pinker formations behind, a hazy ridge beyond and, in the far distance, at the top of the frame, the mountains. A world according to Widforss.

The Grand Canyon in numbers

Grand Canyon National Park (nps.gov/grca/index.htm), designated by an act of Congress on February 26 1919 (and recognised as a World Heritage Site in 1979), covers an area of 1,904 square miles, making it bigger than the state of Rhode Island (1,212 square miles).

The canyon is a mile deep on average, 277 miles long and 18 miles wide. As the California condor (reintroduced in the area in 1996) flies, Grand Canyon Village on the South Rim and the lodge on the North Rim are only about 10 miles apart. However, to drive between them through the park, over the Colorado River and loop around the canyon, you have to travel 215 miles, or for about five hours.

The ultra-runner Jim Freriks – a nurse in Flagstaff – blazed down from the North Rim and up to the South Rim in 2hr 39mins and 38secs in October 2017. Then he he went in for the first of three consecutive 12-hour shifts at the hospital.

The canyon itself can influence the weather. Elevation ranges from around 2,000ft to more than 8,000ft, and the temperature generally increases by 5.5 degrees with each 1,000ft loss in elevation.

The Colorado River began carving the canyon about six million years ago. The oldest human artefacts found there are nearly 12,000 years old and date from the Paleo-Indian period. The park has been used and occupied continuously since that time.

The year the park opened, the canyon drew 44,173 visitors; now there are an estimated 5.9 million a year. The centennial celebrations (nps.gov/grca/getinvolved/centennial.htm) are likely to increase numbers, so prospective visitors should book accommodation well in advance.

“100 Years of Grand” (lib.asu.edu/grand100) – a project of Arizona State University, Northern Arizona University and Grand Canyon National Park – brings together thousand of photographs, documents and correspondence relating to the park’s history.