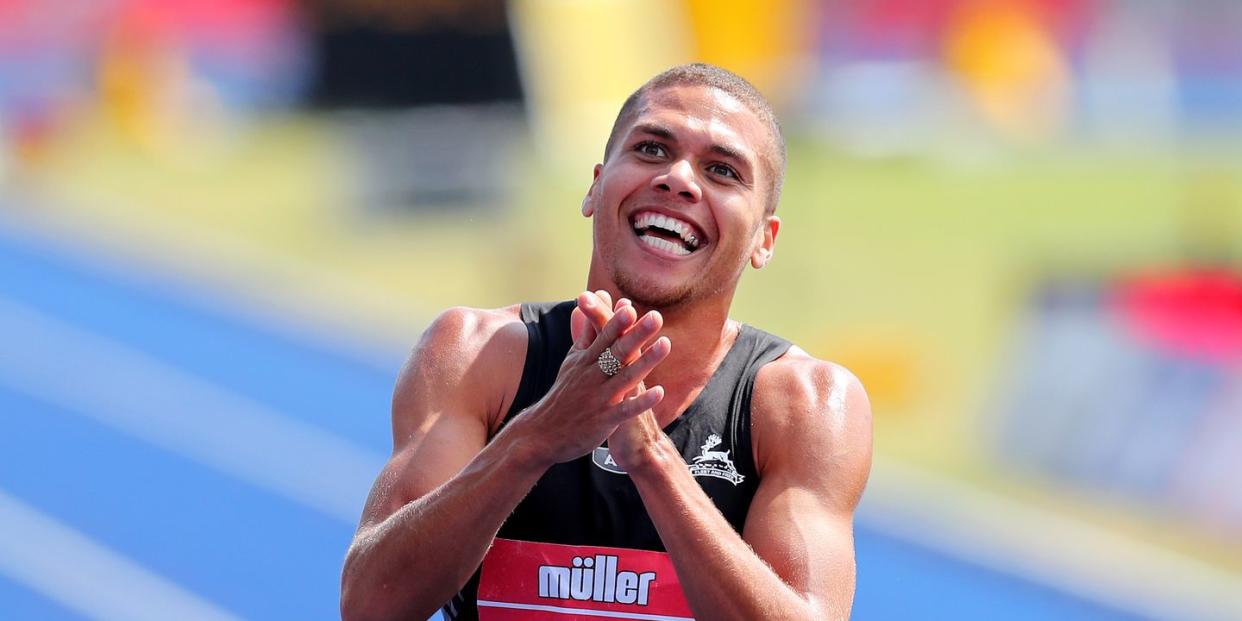

Six things you should know about record-breaking athlete Elliot Giles

It’s an exciting time to be a middle-distance runner in the UK. The current crop of running hopefuls is one of the most thrilling cohorts the country has seen since the heyday of Seb Coe, Steve Ovett, Steve Cram and Peter Elliot.

But in a crowded field, Elliot Giles is attracting some serious attention. His 1:43.63 run in 2021 knocked a second off Coe’s long-standing British indoor record. Only Kenya’s Wilson Kipketer has run faster indoors.

Ahead of what’s bound to be an attention-grabbing summer, where he's set to run the 1,500m in the Commonwealth Games and potentially the European Championships, here are six things you really should know about Elliot Giles.

He was almost turned away from his first running club

Giles was always a sporty youngster, but he decided to give running a go after he left school at age 16, having grown bored of other sports. He turned up at Birchfield Harriers, his local club, but was turned away, as the club had a long waiting list.

That could have been the end of Giles’ running career – before it had even begun. But just by chance, Giles’ first coach Eddie Cockayne was walking past at the exact moment he was rejected at the registration desk.

Cockayne said, ‘I’ll take him on. Let him come with me and I’ll give him a trial,’ Giles told Runner’s World UK. And the rest, as they say, is history.

His burgeoning career was nearly ended by a motorcycle accident in 2014

In 2014, Giles had just battled his way through three years of consistent injuries. He had a PB of 1:53, which was a good way short of what he needed to be taken seriously. Then, in July, he was knocked off his motorbike while picking his younger brother up from a rugby training session.

Giles told RW UK how the horrific crash happened: ‘I was in the left lane of a three-lane road leading up to a set of traffic lights. A lady in the far-right lane made a late manoeuvre, jumping across two lanes, not realising I was coming up to go past the lights. So as she came across, she side-swiped us.’

Giles’ brother was thrown over the top of the bike, while the runner’s knee was crushed between the two vehicles. Giles was tossed to the side, being knocked out when his head hit a bollard. He was left with serious injuries, including brain damage, a torn ligament in his knee, a ruptured glute and bruising on his lower back that made him feel as if his back ‘almost wasn’t a part’ of him.

But that crash made him the athlete he is today

While he recovered, Giles couldn’t move from his bed for three weeks. He urinated in a milk bottle and couldn’t defecate. At one point, the skin started peeling right off his hands. Giles said he had never experienced a low like it.

But that dark period was also the beginning of the record-breaking runner we know today. Whereas before the crash he was plagued by constant cycles of injury, this period of recovery helped Giles gather himself and rebuild at his own pace. Coach James Brewer, who was based at St Mary’s University at the time, was a crucial part of his redevelopment, Giles said.

‘He is largely the reason I was able to put the pieces of the puzzle together,’ Giles said. ‘He slowed me down whereas, prior to that, I was stuck in a cycle of run for six weeks, get injured, run for six weeks, get injured.’

Since rebuilding, Giles has an unusual training regime

In contrast to what you might expect from an elite runner at the top of his game, Giles does three running sessions a week, with the occasional drill session on top. Three.

He explained: ‘I’d had so many calf tears and Achilles issues that something had to change. I had to figure out a different way to train because I knew I didn’t need the same running load as the other guys to compete at the world level.

‘What I needed was consistency, because consistency trumps talent every time,’ he said. ‘The way to get that consistency was to focus on the key sessions and top up the rest with cross-training.’

Giles set up an electric bike company, inspired by his father’s battle with Covid-19

When Giles’ father caught Covid-19, his family were told to prepare for the cruellest of news. After suffering at home for 10 days he was taken to hospital, where his condition was so poor that doctors started to prepare his family for the worst.

But that wasn’t the end of the story. Though doctors were unable to say exactly why or how, Giles’ father recovered – and recovered so well that he was able to go on a health kick, starting with a tricycle he was gifted for Christmas, later turned into an electric trike by Giles.

That was the start of a new venture for Giles: VanderVolt, a play on his father’s middle name of Vandervelt, converts regular bikes into electric ones using equipment bought from overseas. Giles either sells the equipment to customers or kits the bikes out himself, though the company has been successful enough to enlist a couple of friends on occasion.

Giles told the Evening Standard: ‘It’s a budget alternative to extortionate bikes, and it all took off from two Facebook posts. If you don’t take a swing at something, you’ll never know. So, it’s exciting to see what will happen.’

He added: ‘Life is now not just running. Don’t get me wrong, running will always be number one during my career but, when just running, I had blinkers to the bigger world out there. Now I’m learning how to make a business and it seems to be helping to make me run faster.’

He only runs 15 miles a week

Due to repeated calf tears and issues with his Achilles, Giles now only runs a total of 15 miles over three sessions a week. ‘I had to figure out a different way to train because I knew I didn’t need the same running load as the other guys to compete at the world level,’ he said. The rest of his training consists of cross-training, in particular putting in a lot of time on the ElliptiGO trainer, a kind of stand-up bike.

‘It’s about 33 percent harder than cycling and my challenge is to keep up with a group on bikes,’ he added.

‘I know I’m getting a real workout because I often bonk. I push myself so hard that I start seeing stars and shaking, so I’m definitely working as hard; it’s just that my training takes a different form. And it shows that you don’t necessarily have to run big mileage, which is why a lot of athletes get injured.’

You Might Also Like