Are Fitness Influencers a Force for Good?

The modern fitness influencer is a conundrum: spreader or debunker of misinformation? Unscrupulous product-pusher or credible content-creator? Relatable or unattainable? Whether or not you ‘like’ the idea, influencers are now the UK’s main source of health and fitness info. But how did we get here? And does everyone deserve a platform?

Trainers hated Mike Chang. At least, according to the online ads for Six Pack Shortcuts, the company Chang co-founded and fronted, they hated him. And his ‘crazy’ abs. In the early 2010s, both ads and abs were inescapable. ‘Try this one weird trick and get ripped!’

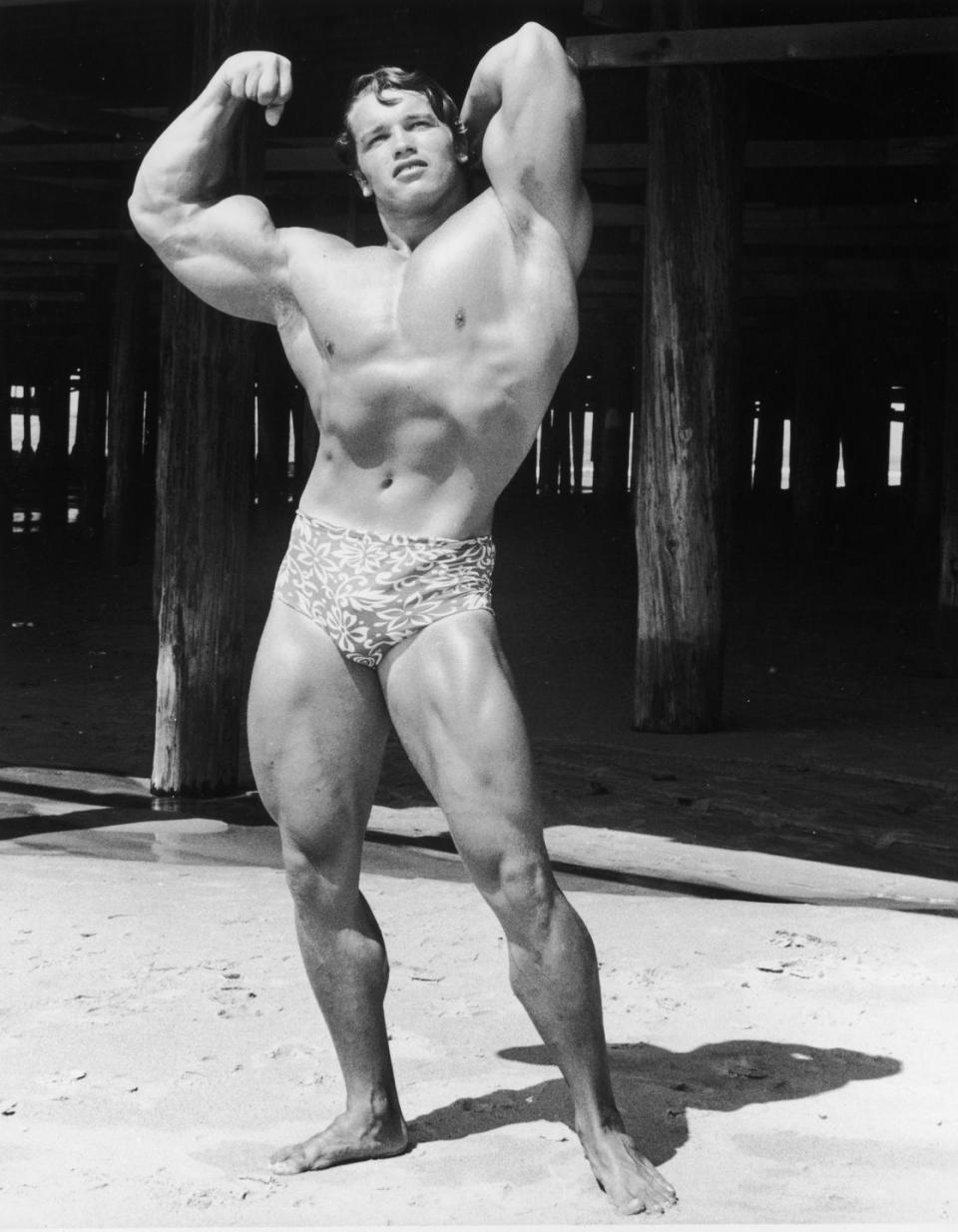

Chang’s fitness influences when growing up were Arnie and Sly, Bruce Lee and Jet Li. Chang admired their confidence; meanwhile, working out helped him build some of his own and – in a rough suburb of Houston, Texas – feel safer. He started lifting weights at 11. By 18, he was working in a gym doing bits of unofficial training, but mainly selling memberships. He also sold newspaper subscriptions door-to-door for years, learning to hide his self-doubt when talking to people, but also to ask himself, ‘What are they looking for?’

Working in real estate, Chang met a guy who understood internet marketing, which was a novel concept a decade ago – as was selling digital products, such as workouts or diet programmes, with no manufacturing or shipping costs. And where an offline trainer can only coach so many people, Six Pack Shortcuts was easier to scale. From the co-founders’ bedrooms, the company grew to an office of 60 employees, including copywriters crafting iconic clickbait – such as the ‘revolutionary new’ fast track to abs discovered by ‘scientists in China’ that enticed over four million YouTube subscribers.

Chang doesn’t blame those who have accused Six PackShortcuts of scamming because, at times, he concedes, the aggressive marketing ‘pushed across the line'. Looking back, he says, there were things he and his colleagues could have done differently. ‘But, equally, I think we created a massive amount of impact.’ They also created a massive amount of money – $13m a year, with plans to scale to$500m. But after a spiritual awakening involving psychedelics nearly eight years ago, Chang exited Six Pack Shortcuts and embarked on a journey into his consciousness that took him, eventually, to Bali. There, now pushing 40, muscles less jacked but abs still crazy, he runs a ‘community’ calledFlow Tribe that combines strength training, stretching, breathing, meditation and tap massage.

Years after leaving Six Pack Shortcuts – now SixPackAbs.com, still with over 4m subscribers – Chang receives messages from people who clicked the ads, watched the free workouts and ‘changed their lives’. On one YouTube video by another fitness influencer, who Chang says is ‘absolutely full of shit’ and ‘should be in jail’, commenters almost uniformly praise Chang as the person who got them into exercise, the ‘true OG of YT fitness’.

Truth and Lies

Social media has democratised content creation and platformed previously unheard voices. Where before you had to buy a book, magazine or DVD, a Zuckerbergian wealth of knowledge on health and fitness is now available at no cost – other than your personal data to target the accompanying ads. According to market research firm Mintel, fitness influencers have become UK consumers’ main source of healthy-living information; studies repeatedly show that, compared with other types of advertising and traditional celebrities, influencers are perceived as more informed, credible and trustworthy – the more followers, the more reliable. But for every influencer creating relatable, nuanced content, there’s a Liver King – real name Brian Johnson – who preaches the benefits of raw offal and bull testicles alongside a dose of his ‘ancestral supplements (link in bio)’. In this wild west, it can be hard to discern the cowboys and native ads.

Indeed, social media has emerged as ‘the most exploitative frontier of late-stage capitalism’, according to journalist Symeon Brown’s recent book, Get Rich Or Lie Trying: Ambition And Deceit In The New Influencer Economy. An influencer, in Brown’s definition,

is someone who converts ‘the new type of currency’, influence – in the form of social-media following – into the old type of currency, money. (The UK Advertising Standards Authority defines anyone with over 30,000 followers as a ‘celebrity’.) The ensuing ‘dogfight for followers, fame and, ultimately, fortune’ is, writes Brown,‘warping human behaviour both on-and offline’; deception is ‘lucrative and becoming increasingly extreme’.

In the sphere of fitness, Brown’s book calls out Shredz, a supplement brand that grew rapidly through influencer marketing – or, in the words of a former employee who recruited them, ‘people who were just fit on Instagram’. But some Shredz athletes were later accused of tweaking their physiques via photo manipulation. One, Devin Physique (né Zimmerman), apologised in a video he later deleted for ‘touching up’ his images. Even though, he claimed by way of mitigation, everyone in the industry did it.

Photoshop isn’t the only means by which some fitness influencers surreptitiously enhance their physiques. Already in cover-model shape, Tom Powell says he didn’t take steroids until after his 2016 appearance on reality TV show Love Island. His profile duly raised, Powell found himself rubbing deltoids with the influencers he idolised growing up as a fitness-mad lad in South Wales.

According to Powell, conversations confirmed his suspicions that ‘everyone in the industry’ was on gear. ‘I was like, “Shit!”’ says Powell.‘“If I want to compete in this industry...if I really want to be a fitness influencer, I’ve got to take it, too.”’

Now an online coach, Powell underwent an operation in April for gynaecomastia – enlarged male breast tissue, one of the side effects of his steroid use – at Signature Clinic, a cosmetic surgery group that has also treated fellow online coaches Jay Gardner (of Geordie Shore fame) and Jake Lawson – although their own reasons for undergoing the procedure are unclear. All three procedures were videoed for YouTube by Signature.

Photo manipulation and steroid use are, of course, old fitness industry and media tricks: Arnie has admitted using steroids during his bodybuilding career; Sly was busted by Australian customs in 2007 with human growth hormone –not a steroid, but not exactly whey protein either. Of course, not every fitness influencer is on steroids. But some are. Others profit from transparency, openly advising on steroids and SARMs (selective androgen receptor modulators). Some influencers claim to reveal the old type of media’s trade secrets, touting Hollywood stars’ supposed steroid cycles for certain roles – which, even if true, probably wouldn’t be known to a random guy on TikTok.

Comparison Culture

Influencers get a bad rap, but the fitness industry has long been economical with the truth – for economic gain – and under the sway of magnetic personalities with attractive physiques. Bodybuilder Charles Atlas (real name Angelo Siciliano) didn’t get his body via the ‘dynamic tension’ system he developed in the 1920s –dubbed ‘dynamic hooey’ by one rival – and the US Federal Trade Commission ruled that it wouldn’t work for others, either. Yet Atlas – and his ad exec business partner – built a mail-order empire around the workouts that transformed the former ‘weakling’ into ‘a complete specimen of manhood’. Plus, Atlas received letters, even after his death, from satisfied customers of ‘dynamic tension’. So was he a legend or a scammer?

Eugen Sandow, the father of modern bodybuilding, made his name (or stage name – he was born Friedrich Müller) by exposing Victorian strongmen who’d break trick chains or invite audience members to try to lift sand-filled barbells that would then be secretly drained. While genuinely strong, Sandow demonstrated that looking strong was more marketable, parlaying his six-pack abs into a chain of upmarket gyms, a magazine and home-workout equipment.

Formulated in the 1950s, ‘social comparison theory’ holds that we seek to evaluate ourselves based on how we stack up against others. ‘Upward’ comparisons to those we view as above us can serve as motivation for self-improvement, but can also lead to body dissatisfaction and disordered eating. Both social and traditional media –including magazines – have been associated with such negative effects. But beyond its sheer volume of content and round-the-clock accessibility, social media is ‘particularly insidious’, explains Marika Tiggemann, Matthew Flinders distinguished emeritus professor in psychology at Flinders University, Australia, and a leading expert on media effects.

This is because social media is ‘the domain of peers’, says Professor Tiggemann. ‘Influencers still present as your friends.’ Social comparison occurs primarily with those we see as being similar to us; Hollywood actors can be dismissed as unrealistic ideals. Because of its relatability, researchers suggest, social media can slip past our defences –especially fitness content, Professor Tiggemann warns, because we think it’s ‘good and healthy’.

Scott Fatt is an academic at Western Sydney University and co-author of the first study to focus on men and fitspo. In his research, looking at fitspo itself wasn’t significantly correlated with poor self-image. But men who viewed fitspo were more likely to compare themselves with others, and Dr Fatt and his co-authors cited ‘a growing body of research... that fitspo is more tightly linked with the appearance of health, rather than health itself’. Similarly, a 2019 study, published in The Journal Of Strength And Conditioning Research, found that muscular PTs were perceived to be smarter and more competent than their less-muscled peers.

A recent study by the Paris School of Business found that watching fitness influencers on YouTube did increase motivation to exercise – but only for those who already exercised, making cause and effect harder to pick apart. Influencers’ habits and bodies might be seen as more attainable – and therefore more motivating – than those of, say, elite athletes. Even so, the researchers noted that many ‘fitness followers’ did not exercise and viewed content primarily as a form of entertainment.

Style and Substance

A former carpenter and roofer respectively, John Chapman and Leon Bustin christened themselves the Lean Machines when they started what was perhaps the first UK fitness channel 11 years ago, because the prominent, predominantly American influencers the pair looked to, including Chang, were ‘probably double the size of us’. At that time, 'everything was about six-packs, everything was topless’, says Bustin. ‘Still is, to be honest.’

Then PTs at a gym in their native Norwich, Chapman and Bustin filmed content from 10pm after it shut. They didn’t, says Chapman, view YouTube as an earner, much less a career – just a way to give people advice and maybe win some extra clients. The pair felt going topless would devalue their knowledge so wore branded vests for about six months before they caved to the imperative for growth. Tops off, the love picked up but so did the hate, which impacted Chapman more when he was younger. The savagery, he’s learnt, often reflects where people are in their lives; he’s DM’d harsh commenters who’ve turned out to be suicidal. The comments have since changed to reflect his shift in priorities from bodybuilding to CrossFit and calisthenics, while Bustin has gotten into ultras.

Harder than going topless for Chapman was selling himself, which didn’t come as naturally to the Brit as it did Americans. In the early days, disappointing video views would detrimentally impact his mood. While social media has for him been hugely positive overall, it’s ‘extremely hard’, he says, to make a career of it without being affected negatively. (Chapman’s brother Jim and sisters Sam and Nicola are all successful non-fitness influencers, while Bustin’s wife Carly Rowena is a fitness influencer.) In creating content to cater for an audience, not yourself, you can, says Bustin, become ‘a character’.

When the Lean Machines started getting bigger and landed a book deal, they stepped away from coaching for a few years to focus on social media. With 430,000 YouTube subscribers and 104K Instagram followers, they’ve now decided to spend more time doing some IRL coaching at their home gyms. Their online coaching is, says Chapman, ‘close to PT’, and gives clients more support than they’d get in an hour at a gym. Appointed last year to the MH Elite, the Lean Machines also sell non-personalised programmes. Sponsored by Nike, equipment manufacturer Wolverson Fitness and sports drink Nocco, they host retreats with CrossFitter (and fellow MH Elite member) Zack George.

Over the years, the Lean Machines, now in their mid-thirties and balancing fitness with fatherhood, have dialled down the toplessness and upped the debunking of misinformation. Their delivery style is comedic, says Chapman, and so exposes more people to good information that alone is ‘not sexy’ (a fair description of most research papers). But the pair say they’re conscious not to put others on blast as some myth-busting fitness influencers do, sometimes viciously. Such self-styled saviours are, says Chapman, really boosting their own credibility by standing on others, which can be ‘a little bit close to bullying’. ‘There are people I really like as people,’ says Bustin. ‘But I don’t like their method on social media.’

These days, more fitness influencers are posting about important topics such as mental health, body image, self-acceptance. They’re honest about the fact that results like theirs take time and consistency. But some, says Bustin, are really just putting up topless shots under a cloak of wokeness in order to chase engagement – and, in at least one instance he knows about, having ‘an internal meltdown about how they live’.

The Lean Machines also post less topless stuff now because they’re conscious that, while not as lean – or jacked – as some, they’re still ‘far above’ a normal body, says Chapman. And a normal body is, says Bustin, ‘so unique and individual’: a balance of physical, mental, nutritional, social and environmental health that looks different for everybody. Body pressure arises, says Chapman, when one (exceptional) type of physique is made to appear the norm.

Equal Opportunity

A child of the early Eighties born with one leg, Tyler Saunders didn’t see anyone like him in his (offline) social networks, the media, anywhere: ‘I was “the only disabled kid in the village”.’ Growing up in Hounslow, west London, he threw himself as far as possible into sports at school but had no disabled role models challenging themselves physically; he wasn’t aware of the Paralympics. The game-changer for Saunders was a BBC TV ident - the short clips that run before programmes - featuring three wheelchair basketball players.

After being drafted into Team GB’s wheelchair basketball development squad then playing in Germany for three years, Saunders returned to the UK and qualified as a PT. Working at a gym, he met a guy who owned a video production company: ‘He was like, “Mate, the things you do, there are people with all their limbs, full health, and they’re making excuses. I look at you and think, ‘What’s my excuse?’” To garner online attention, the pair changed Saunders’ Instagram handle to @oneleggedninja and filmed him performing human flags off statues in Trafalgar Square.

Now @iamtylersaunders, Saunders tries to put out content that ‘uplifts’ his 26,000 followers, to show every bit of his life (including being a dad), to educate backed by evidence and to inform while remaining impartial, because what’s worked for him won’t necessarily work for everybody. There’s so much information on social media, he says, that people don’t know who to listen to: in this crowded marketplace, an impressive physique bestows ‘a kind of authority’.

Social media didn’t invent bro science, defined by actual scientist Alan Aragorn on Urban Dictionary as ‘the anecdotal reports of jacked dudes… considered more credible than scientific research’. But image-driven social has made bro science more scalable, at the risk of crowding out more authoritative, less jacked voices.

An impressive physique was, being honest, one of Saunders’ motivations for getting into the gym. Having grown up wanting to fit in, fitness has helped him feel better about himself. He doesn’t mind going topless now, but doesn’t a lot so as not to fall into that bracket or trigger people. A couple of years ago, he culled a ton of bodybuilder accounts that weren’t making him feel empowered. ‘If there’s a negative shift in your state after looking at that content, unfollow them,’ says Saunders, who’s more selective now about who he follows. If someone’s in great shape, cool: maybe they’re training hard and eating well, or maybe they’ve got a stash of photos taken when they were in peak condition that they’re drip-feeding. That more influencers are illustrating the transformative effect of old industry tricks like good lighting and tensing is ‘good in one sense, but a little bit fake sometimes too’. A veiled excuse for another topless shot.

Because of his disability, Saunders has spent most of his life ‘thinking I didn't really have much impact or influence’. He still battles with the term ‘fitness influencer’, and the responsibility of being a role model. But he wants to be the person he didn’t see when he was younger – ‘as cheesy as that might sound’ - and inspire people to not let their self-imposed limitations stop them leading a more active life. One of the great things about social media, says Saunders, is ‘you can find like-minded people, you can find a community, you can find people who are just like you and into exactly what you're into, and you can join that, and have a voice’.

The messages Saunders receives ‘hit home’ because they show his content is reaching people - maybe even another kid with one leg, battling low self-esteem and confidence, wondering what they can do. If Saunders can motivate just one then, he says, he’s ‘done a good job’.

Follow Freely

Not all of these men and women would necessarily welcome the tag of ‘fitness influencer’ – but they’re in the industry, they have an audience and they get the Men’s Health blue tick of approval

You Might Also Like