Have we finally found the personalised hydration tracking Holy Grail? We marathon tested the Flowbio S1 sweat sensor to find out.

Runners are constantly reminded about the importance of good hydration. Drink too little and your performance suffers. Drink too much and you can put your health at risk. Optimum hydration is a balancing act and let’s face it most of us are guessing. But that may be about to change. One company, Flowbio, thinks it’s cracked the hydration conundrum with a wearable sweat sensor that reveals your fluid and electrolyte loss while you run. So can a wearable really help us improve our drinking habits? I took the Flowbio S1 for a test run at the Adidas Manchester Marathon, to find out.

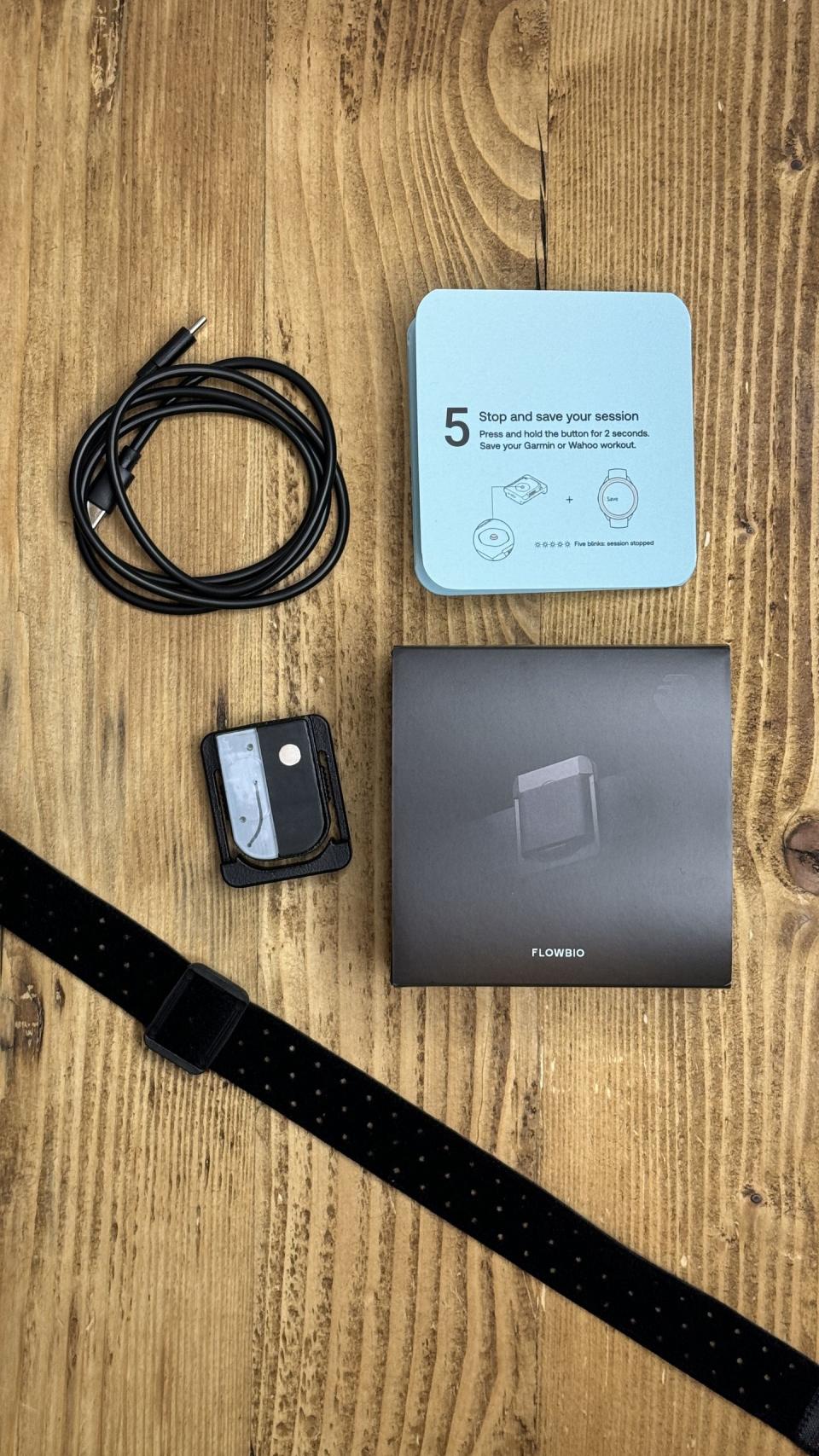

The Flowbio S1: How it works

The 10g Flowbio S1 sensor can be clipped onto any chest strap or arm strap and worn on the back, upper arm and triceps or forearm. It captures sweat in a tiny channel, passes that over a conductivity sensor paired with a high precision skin-temperature sensor, sampling every eight seconds and analysing the fluid and sodium content of your hard-earned sweat.

The data is then fired to an app via Bluetooth, where clever algorithms get to work estimating sweat rate, and sodium loss.

Currently the Flowbio S1 only serves up post-run insights but there are plans to offer real-time guidance, too.

Post-run you get readouts for your estimated total sweat loss, sodium loss, a recommendation of how much fluid and sodium to replace, along with a breakdown of your sweat composition including sweat rate and sweat sodium concentration.

You can also connect your Garmin, COROS, Wahoo and Zwift accounts and Flowbio will pull your run data – like total distance run – into the post-run summary.

The Flowbio S1 battery life lasts for 100 hours of running a single charge and can store up to 80 hours of workouts between syncs. It’s IP55 rated – water and dust-proof – and you can start and stop sessions on the device and run phone-free or by using the app on your phone.

The Flowbio S1 On Test

My first test with the sensor was a low intensity 90-minute treadmill run at the Flowbio labs, in a room heated to about 22 degrees.

During the run, the Flowbio estimated I leaked sweat at a rate of 1.22 litres per hour, lost nearly 2 litres of fluid and 2,000mg sodium with 1,054mg/L sodium concentration.

The Manchester Marathon was the first opportunity to test the sensor in the wild in real world race conditions without the Flowbio team to hold my hand.

How easy is it to use the Flowbio S1?

In terms of set up and use, it’s pretty straight forward. You pair the sensor to an app via Bluetooth, link your Garmin Connect or COROS account so it can pull in your run duration and distance data and you’re good to go.

For both tests, I wore the Flowbio S1 on my tricep though you can clip it onto a heart rate chest strap. Flowbio recommends wearing it on your back.

The sensor is quite chunky, a bit plastic and lacks some finesse. That’s not uncommon for start-up tech, and on the whole it’s relatively comfortable to wear. But there’s definitely room for improvement here, particularly at the price.

The sensor has one main button that’s a tad stiff and not that user friendly, along with a small LED that blinks different colours to tell you when it’s on, connected and tracking. You can start and stop sessions either by hitting a button on the sensor or in the app.

On race day, it took a few attempts to connect and ensure I got the session started, adding some unwanted stress to the start pen. It might be just me but I always struggle to remember the flashing light codes and the combos of single, double, hard presses that put sensors into different modes. And if you’re wearing it on your back that becomes more complicated as you can’t see the lights.

I also couldn’t find any combination of button presses to turn the sensor off the night before, so I had to leave it on charge to make sure it wasn’t dead.

But once Flowbio S1 is on your arm and the session is started in the app, you can largely forget you’re wearing it. Wearing an extra sensor on your upper arm might not be everyone’s cup of tea but I had no issues moving freely in comfort.

Post-run, you’ll need your phone with an internet connection to sync the data. That failed a couple of times for me. But the good news is the sensor stores the session until it has successfully synced.

15 of the best hydration packs and vests

What the Flowbio S1 reveals

Once the data is transferred and crunched by the algorithm, the feedback in the app is encouragingly simple. A few key readouts along with some straightforward actionable advice on how to replace what you’ve lost.

At the Adidas Manchester Marathon, I ran a 2:54:40. A new PB. Go me. The temperature was around eight degrees and the Flowbio S1 clocked my fluid loss at 2.15 litres, with a 0.74 litres per hour leak rate, 2,563mg of sodium loss and a 1,189mg/L sodium concentration.

The first thing to say here is that there’s no way to verify the accuracy of the readouts and you can get alternative benchmark sweat testing done for free, though the method used to take these at-rest tests and the conditions are very different.

Precision Fuel & Hydration’s sweat tests take a protocol used for cystic fibrosis sufferers where chemicals are applied to the skin to stimulate sweat glands and allow sweat samples to be collected ‘at rest’. The sample is put through an analyser to find out exactly how much sodium you’re losing and the results can be used as a useful; a simple benchmark.

My previous sweat analysis tests done with the Precision Fuel & Hydration method put my salt loss at 635mg of sodium per litre of sweat. Based on that data, sweating 2.15 litres would equate to 1,365mg of sodium loss. That’s significantly lower than the Flowbio’s estimate.

The only missing piece of the rehydration equation is your mid-run fluid intake. You have to manually monitor and subtract the volume of fluid you drank during the run. That’s easier to do in training where you might run with your own bottles but in race conditions it was hard to measure how much I’d drunk from water stations.

After the marathon, Flowbio advised me to drink 2.15 litres of fluid and replace 2,563mg sodium. Along the route I probably drank a maximum of 750ml of water, probably less. Had the sweat loss data been available in real time maybe I would have drunk more. But I took on what I could at the time and for the final 10km I was managing a twitchy stomach that wasn’t happy taking too much water on board.

In theory, after the race I needed around a litre and half to rehydrate. I drank at least double throughout the afternoon but I was still peeing dark yellow at 10pm. So I’d suggest the Flowbio acts better as a rough guide rather than a bullet-proof prescription – a useful guide to a minimum fluid intake but perhaps not a replacement for drinking to thirst.

The post-run stats are useful and with more data, over time, it might be possible to spot trends. Knowing how much fluid and salt you lose on average, in certain conditions could definitely help you fine tune your rehydration.

There’s also potential in the future for Flowbio to tailor its feedback to your preferred hydration supplements, so the recommendations would tell you exactly how much of a certain electrolyte product you need post run to replace lost sodium. That could really simplify things.

But it’s really the promise of real time feedback that makes this tech potentially more interesting – at least for runners who need or want to be more precise. The extra insights could improve decision making in changeable conditions. Am I sweating more than usual or maybe less and do I need to adapt my fluid intake?

It’ll be interesting to see what form that takes. It’s always a challenge to balance useful information and alerts that don’t nag or interrupt your run. If Flowbio can nail that – and crucially get those alerts where we can see them on our watch – this immediately becomes a more useful tool for some runners.

However, until that real-time tool arrives, I’d say for most runners – and most runs – the £329 is a big investment to swallow and there’s not quite enough depth to the insights to offer real value.

You Might Also Like