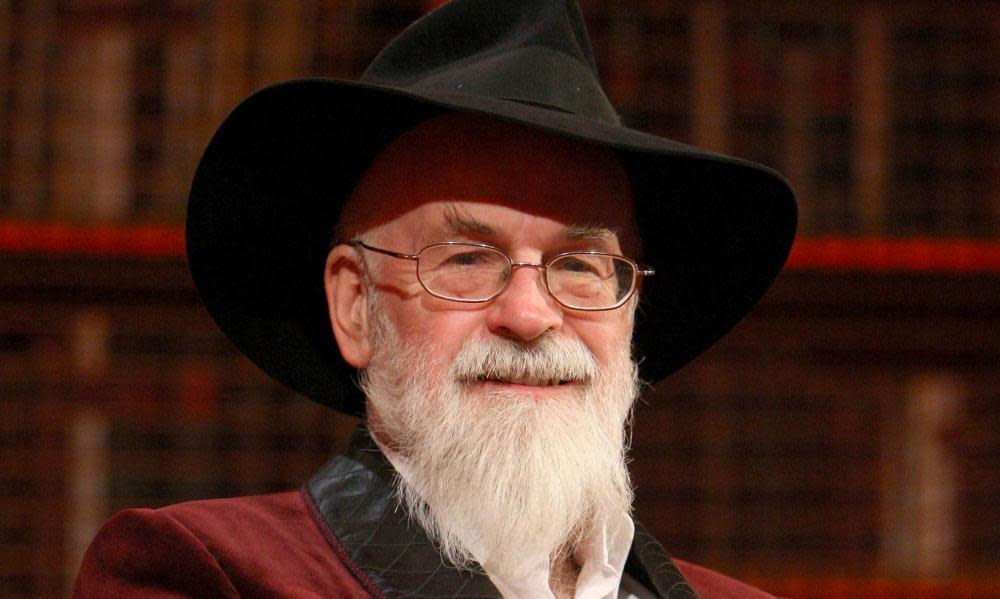

Final Terry Pratchett stories to be published in September

The final collection of early stories from the late Terry Pratchett, written while the Discworld creator was a young reporter, will be published in September. The tales in The Time-travelling Caveman, many of them never released in book form before, range from a steam-powered rocket’s flight to Mars to a Welsh shepherd’s discovery of the resting place of King Arthur. “Bedwyr was the handsomest of all the shepherds, and his dog, Bedwetter, the finest sheepdog in all Wales,” writes the young Pratchett, with typical flourish. The stories appeared in the Bucks Free Press and Western Daily Press in the 60s and early 70s.

Pratchett left school at 17, in 1965, to work at the Bucks Free Press, writing a weekly Children’s Circle story column as part of his new job. He published his first novel, The Carpet People, in 1971, when he was only 23. Editions of the newspapers containing the stories sell for hundreds of pounds online. Dragons at Crumbling Castle, a first collection of the stories, was published in 2014.

Ruth Knowles and Tom Rawlinson, the editors of Pratchett’s children’s books, said when they learned from the author’s longtime agent, Colin Smythe, that there were more early stories, they jumped on them.

Related: The art of Terry Pratchett's Discworld – in pictures

“After reading them, we knew we had to create one final book. It is very fitting that some of the first stories he wrote will be in the last collection by him to be published,” said Knowles and Rawlinson in a statement. “There is so much in these stories that shows you the germ of an idea, which would go on to become a fully fledged Terry Pratchett novel, and so much hilarity that we know kids will love. That is what makes the stories so special – they are for kids and adults, and kids who want to be adults, and adults who are still really kids. Which is exactly who a Terry Pratchett book should be for.”

The stories in The Time-travelling Caveman, published by Puffin, see him exercising his usual dry wit. In The Tropnecian Invasion of Great Britain, he writes: “That was how things were done in history. As soon as you saw a place, you had to conquer it, and usually the English Channel was full of ships queuing up to come and have a good conquer.”

“When it comes to Terry, there is always going to be an embarrassment of riches. His incredible talent and imagination knew no bounds,” said Rob Wilkins, Pratchett’s former assistant and manager of his estate. “With more tales of everything that would go on to make Terry Pratchett books the phenomenon they became – humour, satire, adventure and fantastical excellence – we just couldn’t deny readers these gems, and the chance to read a Terry story for the first time, one last time. It will mean so much to fans.”

Pratchett died in 2015, leaving behind the bestselling Discworld fantasy series, as well as Good Omens, which he co-wrote with Neil Gaiman, and the Carnegie-medal-winning children’s book The Amazing Maurice and His Educated Rodents.

The Tropnecian Invasion of Great Britain

By Terry Pratchett

Tropnecia is a very small country somewhere in the Tosheroon Islands, but once upon a time it very nearly conquered Great Britain.

In AD 411, when the last of the Romans had just left, a small Tropnecian sailing ship that happened to be passing spotted the coast of England, and thought it would be a good place to conquer. That was how things were done in history. As soon as you saw a place, you had to conquer it, and usually the English Channel was full of ships queuing up to come and have a good conquer.

‘If you’ve got nothing to do,’ chieftains would tell their sons, ‘go and conquer England.’

Anyway, the Tropnecians arrived on a Sunday, when there was no one about, so the first thing they did was build a road. That’s another thing you have to do. Either you burn down houses or you build roads and walls, otherwise you don’t stand much chance of being put in the history books.

Tropnecian roads can always be recognised because they never go in straight lines. The roads were all designed by the famous Tropnecian architect General Bulbus Hangdoge, and he wasn’t very good at drawing straight lines. Very good on the corners, but very bad on the straight lines. So all the roads were a little wobbly.

At that time England was full of Picts, Scots, Druids, Angles, Saxons, Vikings, Stonehenges, wet weather and various kinds of kings, the most famous of which was King Rupert the Never Ready, of Wessex. He was never ready for anything, which was why England kept getting conquered.

People would say, ‘Are you ready to fight the Vikings if they try to conquer us?’ and he would say, ‘I don’t think so.’ The next thing you knew, Vikings were all over the place, burning down houses. It was all pretty miserable in those days.

By the time the Tropnecian army had marched into King Rupert’s castle he was feeling more never ready than usual. ‘Are you Romans?’ he said, poking his head out of his bedroom window.

‘No, we’re Tropnecians,’ said General Hangdoge. ‘We came, we saw, we conquered.’

‘It’s people like you who ruin history,’ grumbled King Rupert. ‘The Anglo-Saxons come after the Romans, and they’re not here yet. No one ever said anything about any Tropnecians. Wait your turn.’

And with that he banged the window shut and went back to bed.

The Tropnecians felt rather stupid, standing around with everybody looking at them. They thought perhaps King Rupert had a point – maybe they weren’t supposed to be there, and this was all wrong.

‘I’m going home,’ said General Hangdoge. ‘My feet are wet.’ (It had been raining very hard for a very long time by this point. That’s England for you. If you’re going to invade a place, please do check the weather forecast.)

And so they all marched back to the coast of England*, leaving the way clear for the Anglo-Saxons, who turned up the next day and immediately started to burn houses. And so history was allowed to get going again.

* Along their very wiggly new road.