Fernand Léger: The French artist whose abstract mechanical paintings were called Tubism

The majority of artists who saw active service in the First World War responded to it – artistically speaking – with a mixture of shock, pity and horror. One thinks of Henry Tonks’s portraits of soldiers who’d had their faces hideously disfigured; or Otto Dix’s hellish depictions of life on the Western Front, in his etchings series Der Krieg.

Fernand Léger was different. He served as a sapper in the French army’s engineering corps, taking part in the Battle of Verdun and eventually being invalided out of action after a gas attack. In later life, he reflected only positively on his wartime experience, though, calling it a “blinding reality that was wholly new to me”. He added that he’d been “utterly dazzled by the sight of the breech of a 75-millimetre (gun) in full sunlight, by the magic of light on bare metal”.

He was also dazzled by the tanks, planes and other technological innovations he saw at the front, and his art soon reflected this. The years between 1918 and 1923 have become known as his “mechanical period”, his work from the time reflecting an infatuation with machinery. Motors, turbines and bridges all feature – as do aeroplane propellers, which he described as pieces of manufacturing so “clean, precise and beautiful [they’re] the most terrible competition an artist has ever been subjected to”.

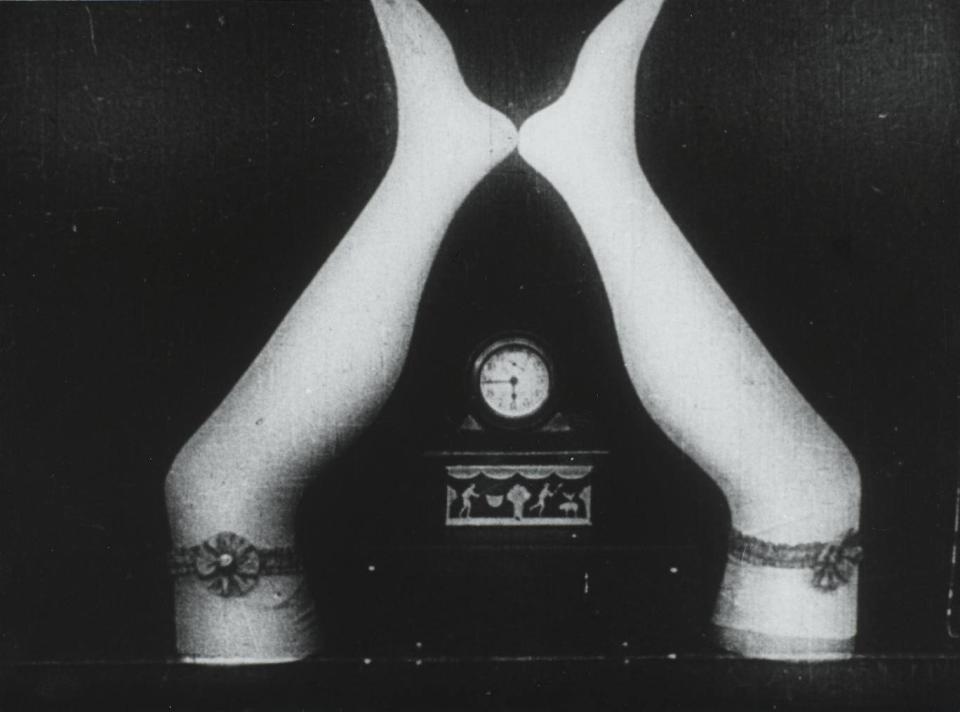

Léger’s embrace of modernity also extended to his choice of medium. Though predominantly a painter, he was a huge fan of cinema and hailed Charlie Chaplin as one of the great artists of his day. In 1924, Léger even made his own film, Ballet Mécanique: an experimental, narrative-free piece featuring 300 shots in just 12 minutes, with pistons, carnival rides and egg whisks among the fleetingly captured subjects.

The film is to be screened as part of a major exhibition opening at Tate Liverpool on Friday, Fernand Léger: New Times, New Pleasures. Remarkably, this is the first big UK show dedicated to the artist in 30 years. I say “remarkably” because Léger was once talked of in the same breath as Picasso. Indeed, in 1935, he became one of the first artists to have a retrospective at the new Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York, a full four years before the Spaniard did.

Both men were born in 1881: Picasso in Malaga, Léger (the son of a cattle breeder) in Normandy. True to his rugged, rural roots, the latter was tall and stoutly built with weathered skin and a bulbous nose. He moved to Paris in 1900 – the same year Picasso arrived there – and, after brief training as an architect, turned to painting.

His earliest work reveals the influence of the Impressionists, though it was in 1910 that his career can be said to have truly begun: when he turned to Cubism. That revolutionary style had recently been launched by Picasso and Georges Braque, but Léger would develop it as brilliantly as anyone – partly through the introduction of bright colour and partly through the introduction of ovals, cylinders and other rounded shapes. His personal twist on Cubism, in paintings such as Soldier with a Pipe, even came to be given its own name: Tubism.

In ‘The Disc’, like other works from his mechanical period, Léger isn’t trying to precisely represent an object or setting, so much as replicate a modern, speeded-up way of seeing

The Tate Liverpool show will include 50 paintings from across the artist’s career, allowing the visitor to follow Léger’s progress from Tubism via abstraction to his mechanical period – and beyond. Sadly, his frenetic ode to the modern metropolis, 1919’s The City, isn’t being lent by the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

On the plus side, 1918’s The Disc will be on view. It captures the collision of a variety of geometric forms and broken planes. The near-abstract scene is possibly that of a factory interior – but more pertinent is Léger’s observation that “the view through the door of a railway car or automobile windscreen, [at] speed, has altered the standard look of things”. In The Disc, like other works from his mechanical period, Léger isn’t trying to precisely represent an object or setting, so much as replicate a modern, speeded-up way of seeing.

In due course, Léger would head in yet another artistic direction: one which saw the return of human figures to his pictures. Usually, as in Three Women, these were monumental females with powerful limbs and long, wavy hair. Yet again there’s a parallel with Picasso – who at the same time was following a distinctly similar path with his so-called “Neoclassical” paintings such as Two Women Running on the Beach.

In his monograph on Léger, the art historian Werner Schmalenbach referred to the the Frenchman and the Spaniard as “antipodes”, a kind of yin and yang of modernist art. Where “Léger was obsessed by his duty as a painter of the present day, Picasso was a genius who yielded to his moods and fancies,” he wrote.

In other words, Léger was the epitome of an artist utterly engaged with the world around him, while Picasso was that of a solitary artist able to produce masterpieces seemingly out of thin air.

One of the highlights of the Liverpool show will be Léger’s mural, Essential Happiness, New Pleasures, which was first shown in the Pavilion of Agriculture at the Exposition Internationale in Paris in 1937. At 10ft long and almost 4ft high, it takes the form of a photomontage in which Léger – at a time of growing international tension – presented a vision of peace.

The artist was supportive of Léon Blum’s socialist French government at that time, and from the 1930s on his art took an undeniably political turn. Myriad, sympathetic depictions of construction workers resulted, as did speeches at trade union congresses and lectures at universities about why art should be made for everyone not just the elite. (In his latter years, he increasingly sought public commissions: among his final projects was the design of a huge, stained-glass window for the Central University of Venezuela’s main library, in Caracas.)

In truth, Léger’s later work never matched the glorious heights of that before it. There’s a sense of an artist going through the motions. Writing in the 1940s, the influential US critic Clement Greenberg went so far as to say that “by force of repetition, Léger’s painting has become facile and empty”.

And perhaps that’s one reason why, after the artist’s death in 1955, he never went on to have quite the status he deserves – and his reputation suffered. His peers, Picasso and particularly Matisse, offered a template of how the very best artists continued to innovate till the end.

Another factor was surely the triumph, for much of the 20th century, of Formalist art criticism. According to this, the purely visual aspects of a work – ie, its form – mattered more than narrative content. Political causes were a no-no.

Are there signs, however, that things are finally now changing? Two large exhibitions this year – Tate’s and another at BOZAR in Brussels – suggest Léger’s star is on the rise again. As does the sale at Christie’s New York last year of his painting, Contraste de formes, for an eye-watering $70m. At last, there seems to be recognition that this was a trailblazing figure: the modern artist, who more than any other, thrived on modernity.

Fernand Léger: New Times, New Pleasures is at Tate Liverpool from 23 November to 17 March 2019; tate.org.uk (0151 702 7400)