A Father’s Archives

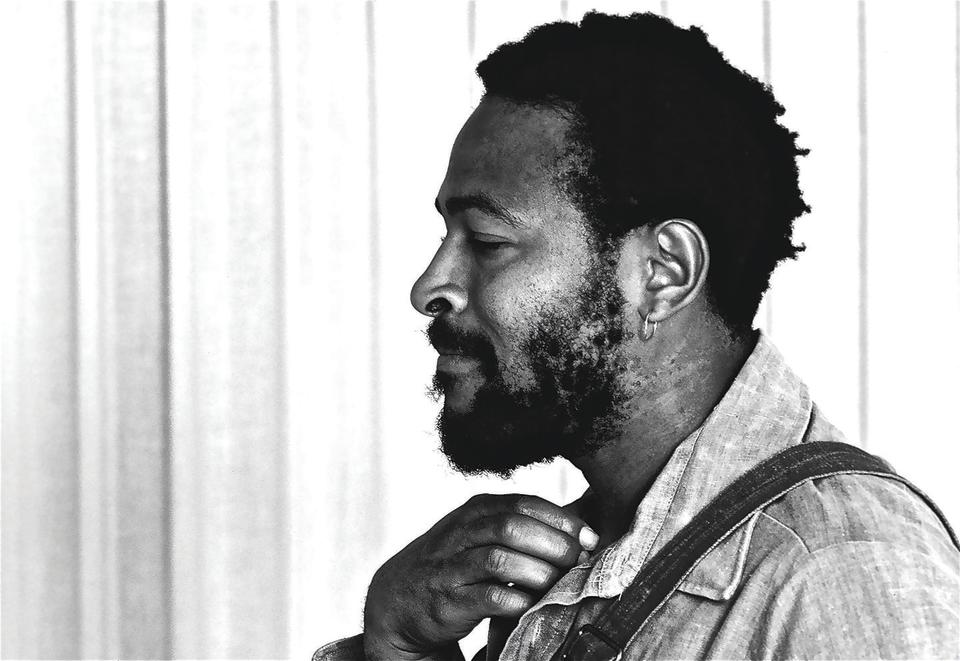

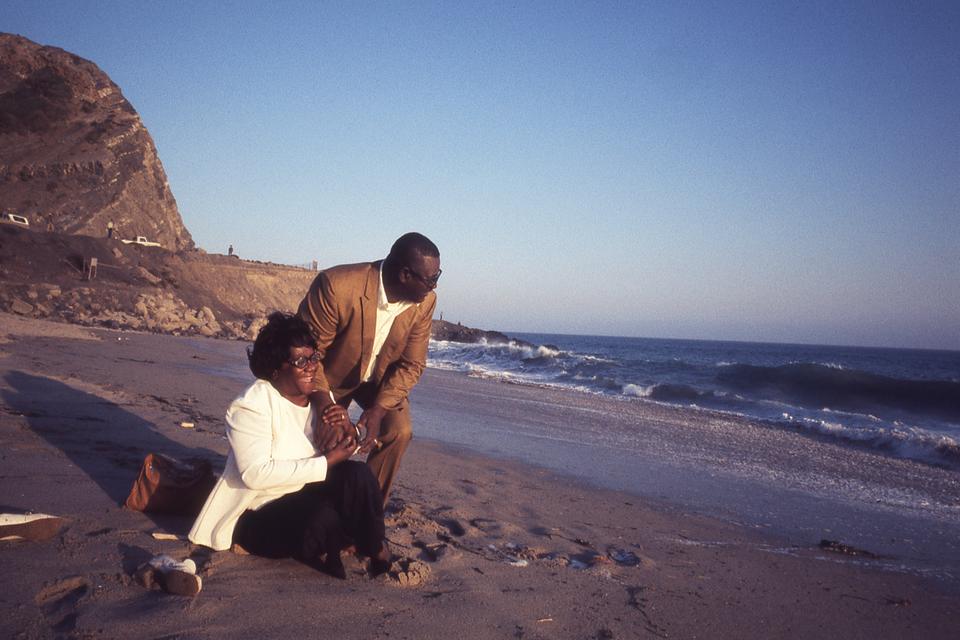

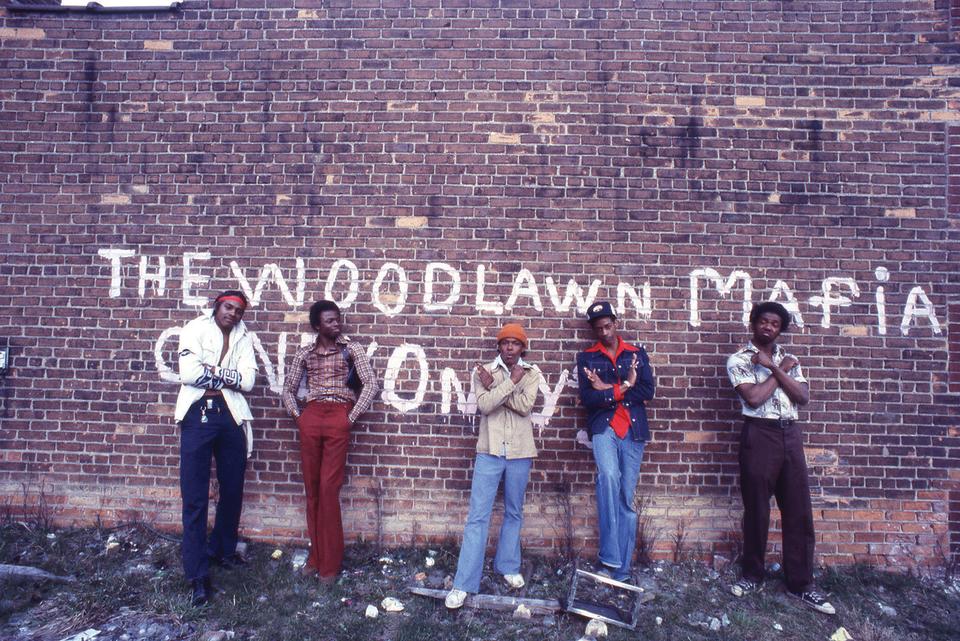

During the pandemic, my father and I wrote a book together about his life as a photographer. My father, Lester Sloan, began his career as a cameraman for the CBS affiliate in Detroit, then worked as a staff photographer in Los Angeles for Newsweek magazine for 25 years. The archive of his work consists of street photography, portraits, news photos, celebrity portraits, key news events like Pope John Paul’s visit to Mexico, Black cultural life in Europe, and the everyday lives of Black folks in Los Angeles and Detroit.

Working on this book with him was a way of spending time together, over Zoom, as we were cordoned off in our own homes, separated by quarantine. It was also a way of traveling— back in time to his childhood in Detroit, across the world to Germany, where he documented the fall of the Berlin Wall, and into the future, when we might be able to move through the world more freely again. Last summer, his archives were damaged by a flood. This has made the act of reminiscing almost therapeutic, a way of preserving those images that were lost. Recently, we sat down together so that I could ask him 10 questions about the arc of his career.

How did you get your first camera?

I won it selling subscriptions for the Detroit Free Press when I was 10. But my first real camera, and by “real” I mean one where you had to know something about photography, was a Pentax. I was working for a printer, and my boss took me to a pawn shop that a friend of his owned. That was my first camera with interchangeable lenses. More or less a point and shoot. I think I still have it.

Who was the first photographer in your life?

It would have to be my uncle, my father’s youngest brother. He took pictures at special occasions, documenting life—say, if somebody came over to dinner or to play pinochle. I guess that was my first lesson in photography, my first lesson in storytelling. Uncle Jimmy took pictures when he was in the military, during the Korean war.

Tell me about Goethe Street.

First of all, we called it “Go-thee,” because I didn’t know any German then. My paper route growing up in Detroit took me from Forest to Mack, and then Goethe started and went two blocks up to Charlevoix, where my paper route ended, and I crossed back to Seyburn and came back to Mack, where the guy who distributed the papers gave me a ride back home. My interest in German started in college. That’s when I found out who Goethe was. At Wayne State University, I started taking German. I don’t know why German instead of French or Spanish. Seems like everything happened when it was supposed to happen, looking back. It’s almost as if my life had been planned in advance. You know when it’s the time to do it.

Like what?

People came along in my life when I was ready to go to a next step. I was working at the Detroit Public Library while I was at Wayne, and Kurtz Myers, the music librarian, he was a person in my life who told me things about myself that I didn’t yet know. He took me to the Shakespeare festival in Canada; he introduced me to classical music. I called Chopin “Choppin,” and Kurtz said, “It’s a funny-sounding name, but it’s ‘Cho-pan.’” He let me down gently. He didn’t say, “You dumb schmuck.” He knew me better than my parents even. He had watched my growth. He was there at a moment when I was taking a step forward.

So what was the next step?

Getting a job when I got out of Wayne. I got a job at Channel 2. Sort of a fluke there too. My job was supposed to be overnight news editor, which meant I listened to the police radio and went out whenever there was a fire or a robbery. I went out with a camera to cover these places, never realizing there was some real danger in covering these things, shootings and gang fights. I would show up in my TV 2 car with my blue blazer. One night, there was an accident on the freeway. An 18-wheeler truck tried to avoid running into someone, pulled up on an embankment, and got stuck with the overpass above, and it created a traffic jam that went on for miles. I processed the film and wrote the copy for the morning news show. This guy went on air and read it, and it was funny. He and I went out to lunch at the press club, and everybody came up to him and said, “That was the funniest thing I’ve ever heard.” He was taking all the kudos and high fives. He said, “Actually, Lester wrote the story and shot it. I just read it this morning.” They didn’t say a word.

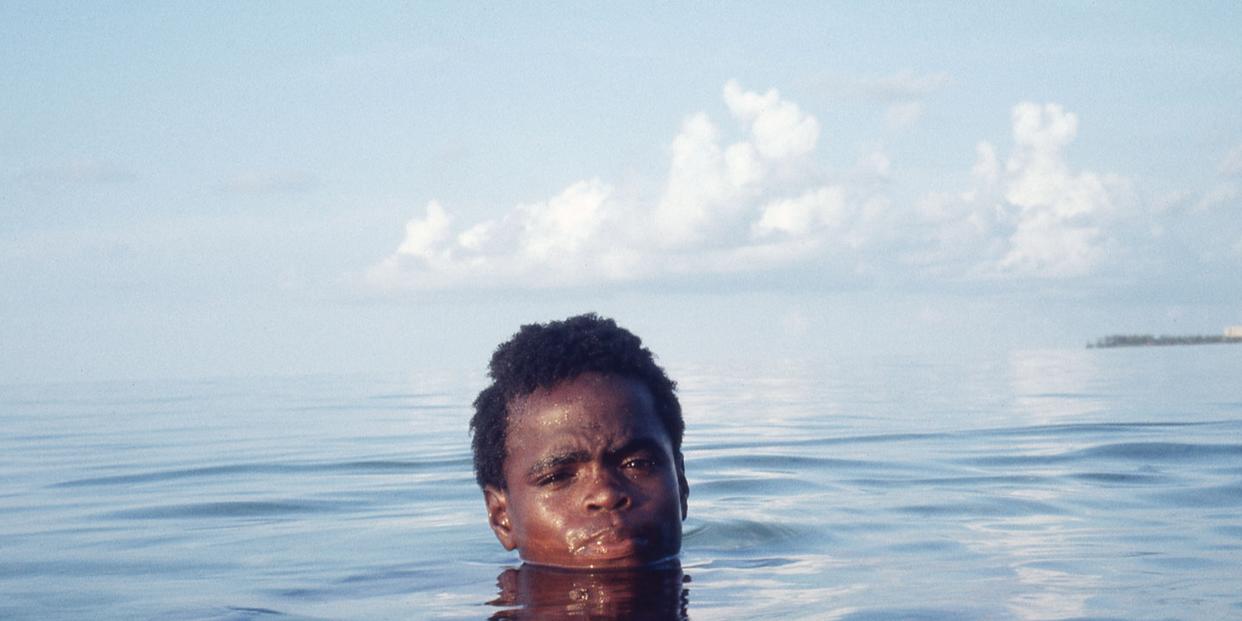

What was your first experience going abroad?

I went to the Bahamas for Newsweek in 1973, when they got their independence. I remember talking to Prince Charles and Prince Philip when they were waiting for the queen to come out of a church, and I was standing right next to the two of them. I asked these young women if I could stand in front of them to get a shot, and Prince Philip said, “What language do you use when you talk to these people?” And I said, “The one that works.” They both cracked up. I was saying, “It’s something between us. You wouldn’t understand.”

What was the next country you went to?

The next time I went abroad was to Europe. I was supposed to work for the Paris bureau, but that fell apart. So I started going to Europe on my own.

When did you encounter Henri Cartier-Bresson’s work?

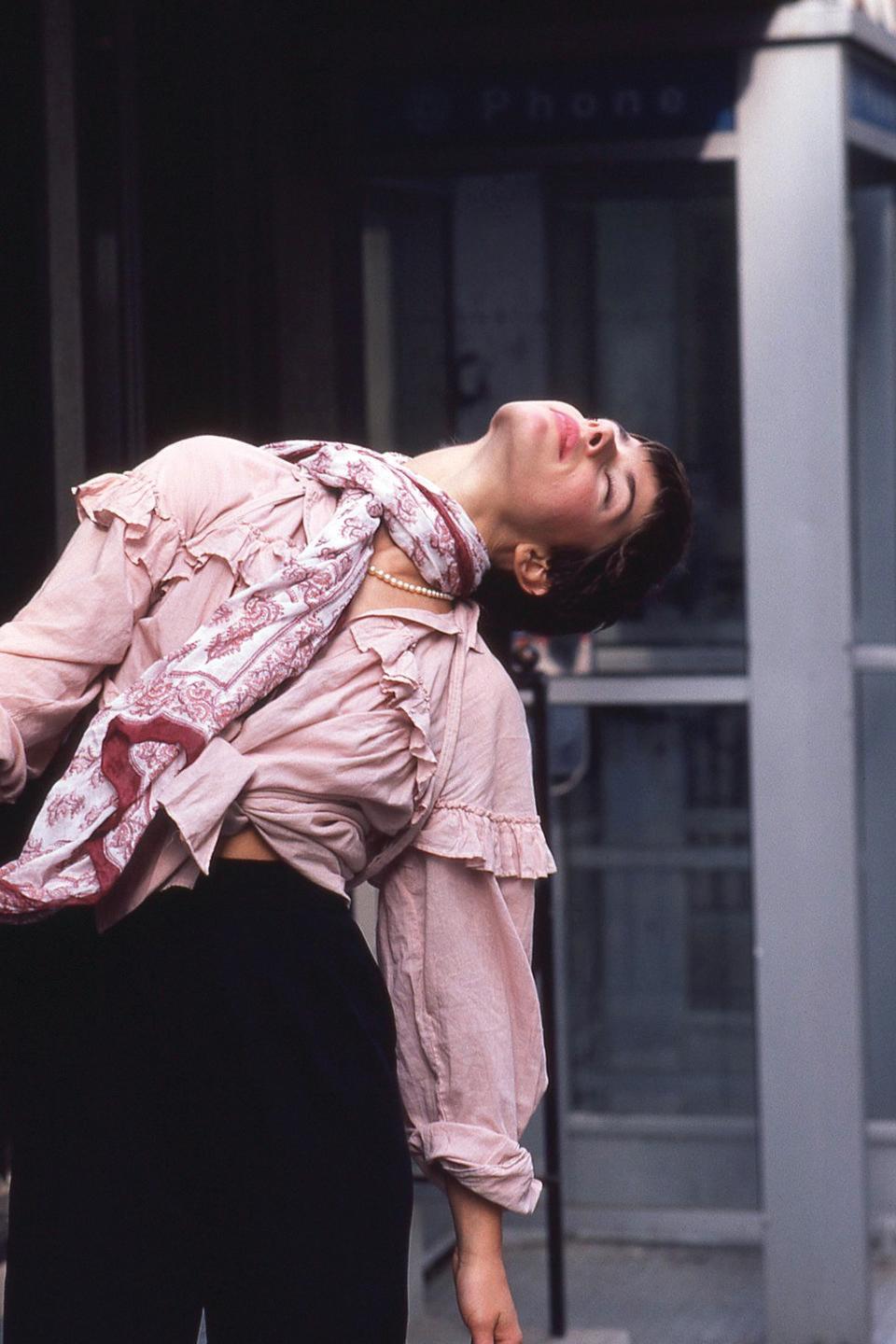

I must have read about Cartier-Bresson. Before they had motor drive cameras, they had regular film cameras. Nothing super fast. Cartier-Bresson was able just by using his hands and his eyes to take exposures of what he called “the decisive moment.” For instance, a man jumping over a puddle: He could take three exposures with a Leica camera, and, of the three, one would be of the man exactly midair, with his legs stretched out. You can take a picture of what’s going on in the streets, and there is a story there, a narrative: a beginning, a middle, and an end. How you do that as it’s unfolding is sort of uncanny. But when you see the results laid out, there it is, perfect. Same thing photographing sports. Now you have cameras that rip off 10 frames in a second. Before, guys would set up five individual cameras, with shutter releases in their hands, and they would fire off all those cameras of some guy skiing down a mountain, and maybe just one of them would be perfect. When motors came along, everybody could do that. But in Cartier-Bresson’s time, you had to be in sync with what was going on around you.

When did you first meet Gordon Parks?

Gordon came to a museum in L.A. for a panel discussion, and I was the moderator. The last time I saw him was at his home in New York. Got there at 8 in the evening and left at 3:00 in the morning.

What would you write about if you wrote a play?

I’d write about the expatriate cartoonist Ollie Harrington. The two of us talking at his apartment in East Berlin. It was almost as if I was attending a seminar when he was speaking: “Don’t step on that, you’ll trip and fall.” I remember when we met up in France, Ollie would look at me and make some sort of gesture, and then he’d say, “Lester and I gotta get out of here.” He would be telling a story, and I’d say, “Let me get this straight.” And he’d sort of lean back and laugh and say, “Thaaaat’s right.”

You Might Also Like