Fascinating archaeological discoveries from recent times

Incredible recent discoveries

ASAAD NIAZI/Getty Images

Modern technology, new excavations and curious amateurs have helped unearth some of the world's greatest treasures in the last 50 years – from secret Maya pyramids and fascinating fossils to astonishing ancient artworks and lost Egyptian cities.

Read on to see some of the most exciting archaeological discoveries of modern times…

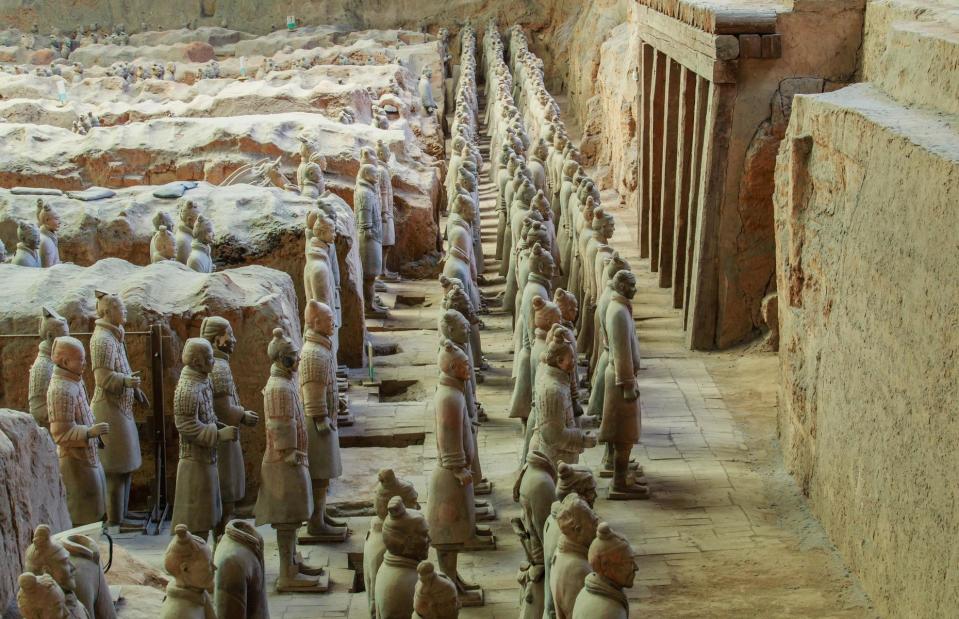

1974: Terracotta Army, Xi’an, China

Kanuman/Shutterstock

In 1974, labourers digging a well in China happened upon a life-sized terracotta soldier. When archaeologists came to investigate, they eventually unearthed thousands of similar figures, standing in trenches. So began one of the most exciting archaeological discoveries in history.

1974: Terracotta Army, Xi’an, China

TuttiFrutti/Shutterstock

There are around 8,000 pottery soldiers and archers, plus 130 chariots and 520 horses housed in three pits taking up an area of 215,278 square feet (20,000sqm). The sculptures are all painstakingly created, with unique facial expressions, detailed uniforms and treads on their shoes. Many were originally painted, although the pigment has faded over time.

1974: Terracotta Army, Xi’an, China

TriciaDaniel/Shutterstock

It’s thought the army was created to guard the body of Emperor Qin Shi Huang, who died in 210 BC and whose tomb lies around a mile away. Today the figures can be found at the Terracotta Army Museum in Xi’an, in China’s Shaanxi Province.

1987: Royal Tombs of Sipan, Peru

Marktucan/Shutterstock

In 1987, a series of burial sites were unearthed near Sipan, on Peru’s north coast. The most intriguing and exciting discovery was a tomb, which housed a wooden coffin, containing a skeleton. It soon became clear this was the body of someone important – he was dressed in a gold mask, holding a shield and wore a headdress and copper sandals. He’d also been surrounded by treasures, including gold bells, a gold and copper rattle and hundreds of gold, silver and ceramic offerings.

1987: Royal Tombs of Sipan, Peru

Ecuadorpostales/Shutterstock

Now known as the Lord of Sipan, experts believe he was an important Mochican warrior-priest. He wasn’t alone in his tomb, either. Three women (most probably wives), a child, two men and two llamas were buried alongside him. Today many artefacts from the find are displayed at the Royal Tombs of Sipan Museum in Lambayeque, Peru.

1989: Rosalila Temple, Honduras

ORLANDO SIERRA/AFP/Getty Images

In 1989 a beautifully preserved pink temple was discovered hidden inside a pyramid in the ancient Maya city of Copan in western Honduras near the Guatemalan border. Thought to date to the 6th century AD, the three-storey structure was buried under mud, plaster and stone.

1989: Rosalila Temple, Honduras

DennisJarvis/Flickr/CC BY-SA 2.0

The temple’s inner walls were coated in soot from torches and, inside, several religious artefacts were discovered, including incense burners, stone pedestals and flint knives thought to be used in sacrifices. Today, a life-size replica of the Rosalila, which features its intricate artwork, is displayed at the Sculpture Museum in Copan (pictured).

1990: Balamku, Mexico

HJPD/Wikimedia Commons/CC BY 3.0

The wooded Maya site of Balamku, home to the terraced stone Temple of the Jaguar, was discovered in Mexico’s Campeche state by archaeologist Florentino Garcia Cruz in 1990. Sadly, treasure looters had arrived before the experts, but luckily they’d not stolen the site’s greatest treasures.

1990: Balamku, Mexico

HJPD/Wikimedia Commons/CC BY 3.0

Most extraordinary of all Garcia Cruz's discoveries were the site's intricate stucco friezes thought to date from between AD 550 and 650. The ornate frieze in the Temple of the Jaguar, depicting a king and a series of complex patterns and symbols, was the largest Maya frieze ever to be discovered at the time at 55 feet (17m) long. Today, a guard stands watch over the temple and its precious artefacts daily.

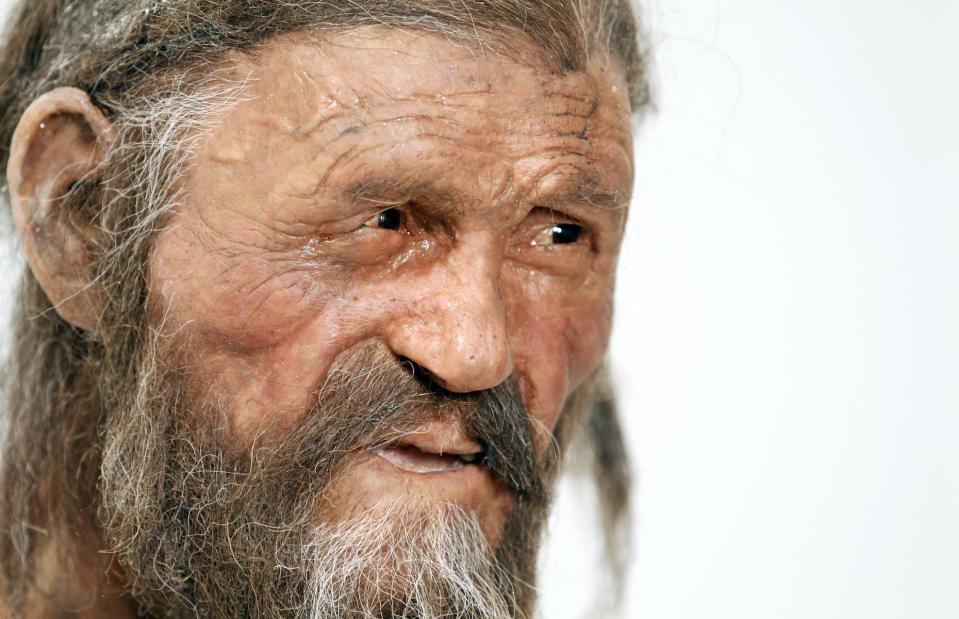

1991: Otzi the Iceman, Italy

Andrea Solero/AFP/Getty Images

The frozen remains of a body that is older than the Egyptian pyramids and Stonehenge was discovered by hikers in 1991 on the Schnalstal/Val Senales Valley glacier between northern Italy and Austria. It was later determined that the Copper Age man – soon to become known as Otzi the Iceman – was brutally murdered. His body lay preserved naturally in the ice for 5,300 years along with his clothing and equipment. Pictured here is a reconstruction of Otzi, created using forensic technology in 2011. The landmark 'wet mummy' is now displayed in a specially devised cold cell in the South Tyrol Museum of Archaeology in Bolzano.

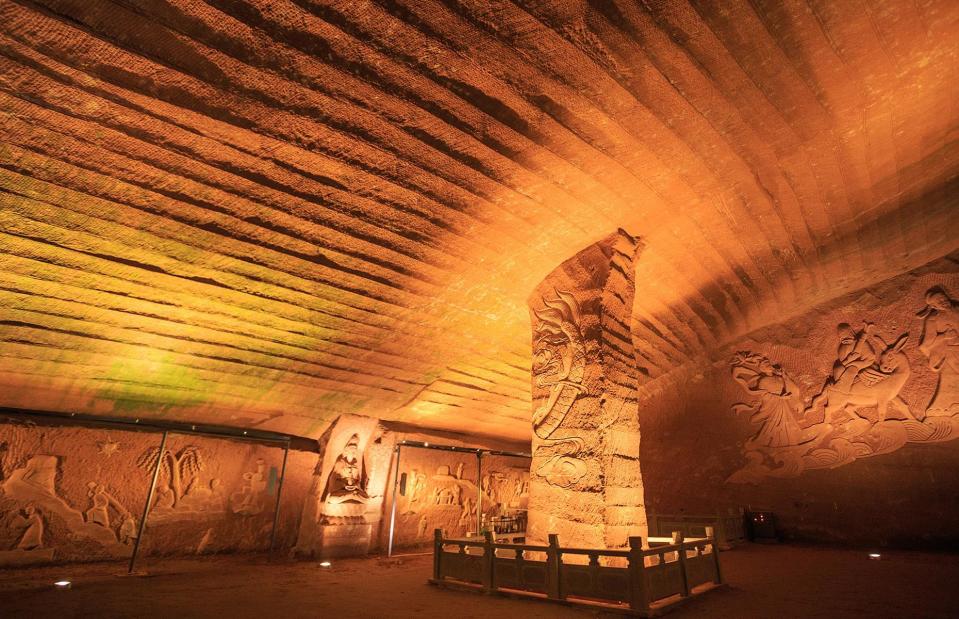

1992: Longyou Caves, China

Zhangzhugang/Wikimedia Commons/CC BY-SA 4.0

This curious set of man-made caverns in eastern China, also known as the Xiaonanhai Stone Chambers, was discovered in 1992 by a local man named Wu Anai. He became intrigued by the many large and deep ponds in the area. So, using a water pump, he drained a pond which revealed the mouth of a cave. Curious villagers then proceeded to drain a series of other pools in the vicinity until an impressive complex of 24 grottoes was unearthed.

1992: Longyou Caves, China

Zhangzhugang/Wikimedia Commons/CC BY-SA 4.0

Though subsequent research concluded that the caves are man-made and thought to date back some 2,000 years, their purpose remains a mystery. Also unclear is exactly how they were constructed in the sandstone hills – reaching a height of 98 feet (30m) in some spots, their formation would have been no small feat. They include pillars and carvings of lines and symbols.

1992: Zeugma mosaics, Turkey

Cornfield/Shutterstock

The ancient city of Zeugma was originally founded by a commander of Alexander the Great in the 3rd century BC. Yet these spectacular floor mosaics were discovered much more recently in the 1990s. However, in 2000, the Turkish government built a vast dam just a mile away from the archaeological site, which threatened to leave the area submerged under water. This triggered a desperate attempt to excavate and save as many of the mosaics as possible before they were lost forever.

1992: Zeugma mosaics, Turkey

Akturer/Shutterstock

The colourful glass floor mosaics, which were discovered in Zeugma's Roman villas, are now on display at the Zeugma Mosaic Museum in Gaziantep, Turkey. Built to house them in 2011, it’s now the largest mosaic museum in the world. Three more incredibly well-preserved mosaics were uncovered at the ancient city of Zeugma in 2014, including one of the Nine Muses.

1994: Gobekli Tepe, Turkey

Cornfield/Shutterstock

Until 1994, Gobekli Tepe was thought to be an abandoned medieval burial ground. However, German archaeologist Klaus Schmidt discovered something rather more astonishing – vast limestone pillars set in circles. It’s now considered the world’s oldest religious complex, having been built between 9600 and 8200 BC and predating Stonehenge by around 6,000 years. Six temples have been excavated, but geo-magnetic surveys suggest there could be up to 20 more.

1994: Gobekli Tepe, Turkey

Cornfield/Shutterstock

The megaliths of these circles were carved with lions, scorpions and snakes, and weigh up to 60 tonnes. It remains a mystery how the hunter-gatherers shifted them into position, but the remarkable feat suggests society in the 10th millennium BC was far more developed than we first thought. In early 2017, a report in Science Advances also announced the discovery of three skulls at the site, which had holes and carvings, suggesting they may have been hung on display and that bones were used to honour the dead at this intriguing place. In 2018, Gobekli Tepe was made an UNESCO World Heritage Site.

1994: Historic Jamestowne, Virginia, USA

FelixLipov/Shutterstock

The live archaeological site of Historic Jamestowne offers a detailed insight into what life was like for the 104 people who established the first permanent English settlement in North America in 1607. Since 1994, when excavations began, the remains of the original triangular James Fort have been found, along with more than 1.5 million artefacts. Burial sites, wells, bread ovens, gun platforms and empty wine bottles have been unearthed, along with thousands of artefacts belonging to the Indigenous Powhatan people, who had lived on the land for 12,000 years before the arrival of the English.

1994: Historic Jamestowne, Virginia, USA

ZackFrank/Shutterstock

The relationship between the Powhatan and the settlers was complex and involved periods of both conflict and peace. Pictured are the remains of the church where tobacco grower John Rolfe (who was among the first to bring enslaved Africans to Virginia), married Pocahontas, daughter of the powerful Chief Powhatan and whose story has often been romanticised in books and films.

1996: Sinosauropteryx prima fossil, China

Mark Brandon/Shutterstock

Hailed as the dinosaur find of the century, the chance discovery of a near-complete skeleton of a small predatory dinosaur in a rock changed the way we understand these mysterious creatures and evolution. Found by a farmer in northeastern China, it was the first fossil that showed evidence of a non-avian species having feathers with a clearly visible fringe of tissue around the body. Named the Sinosauropteryx prima in 1996, subsequent studies have confirmed that the ruff on the chicken-sized fossil was actually early feathers and colourful ones at that.

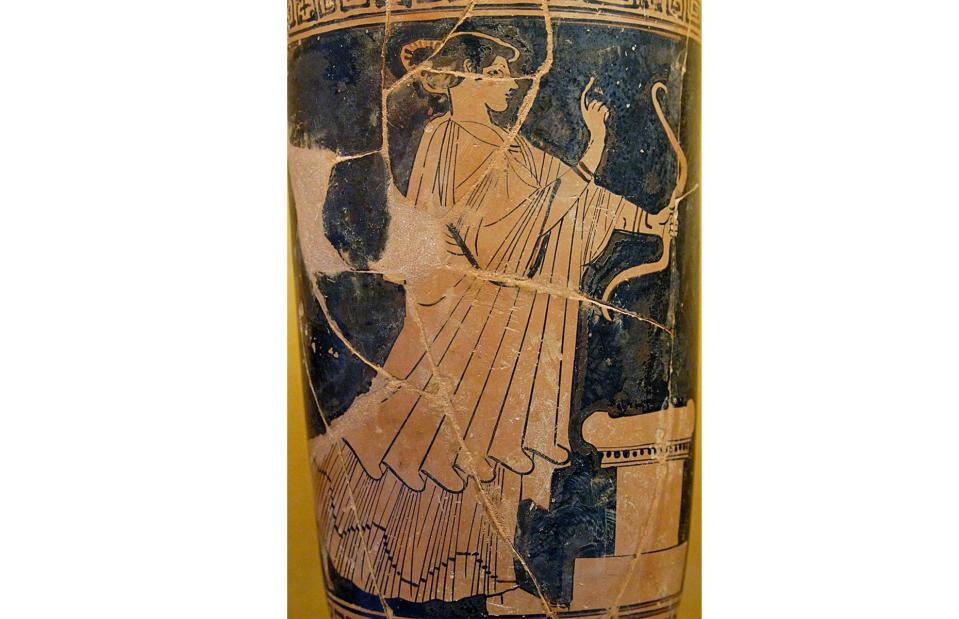

2000 onwards: Selinunte, Sicily, Italy

Stefano Valeri/Shutterstock

Selinunte was an ancient Greek colony in southwest Sicily thought to have been established from around 650 BC. While some 15% of the settlement was already above ground, including its five-strong temple complex, archaeologists were keen to find out more about the settlement and its inhabitants. They have spent the past two decades excavating the site and have uncovered heaps of hidden riches so far. It is now Europe's largest archaeological park.

2000 onwards: Selinunte, Sicily, Italy

Courtesy of University of Bonn

It’s thought that, at its peak, up to 30,000 people lived in Selinunte. But the settlement was constantly fought over by the Romans and the Carthaginians and was probably destroyed during conflict in the 3rd century BC. During the ongoing digs, the most fruitful of which occurred between 2013 and 2015, archaeologists uncovered the remnants of half-eaten meals and half-finished crafts, thought to have been abandoned by panicked and fleeing villagers.

2000 onwards: Selinunte, Sicily, Italy

Marie-Lan Nguyen/Wikimedia Commons/CC BY 2.0

The discoveries have helped build a clear picture of what life in this ancient society would have looked like. Researchers have exposed some 2,500 deserted houses, traced streets and discovered what they assume would have been a kind of industrial zone, where potters would have worked. Around 80 kilns and pottery workshops have been discovered, plus pigments and ceramic fragments. Selinunte is open daily with guided tours available for visitors to learn more about the site's far-reaching history.

2003: the Ness of Brodgar, Scotland, UK

HAWhymark/UHI Archaeology Institute

What was once thought to be a natural hill on remote Orkney in fact turned out to be a vast, Neolithic complex of buildings, covering more than six acres of land. After the nearby Ring of Brodgar became a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1999, radar surveys were undertaken on the surrounding area and, in 2002, a geophysical survey revealed a cluster of sub-soil anomalies, indicative of a settlement. After excavations in 2003, the Ness of Brodgar was unearthed.

2003: the Ness of Brodgar, Scotland, UK

HAWhymark/UHI Archaeology Institute

The huge discovery revealed a massive Neolithic site that predates Stonehenge with some of the buildings dating from 3300 BC. Excavations, which are still ongoing, have discovered walls 13 foot (4m) thick, 90,000 pieces of pottery, bones and tools. On selected dates it's possible to visit and see the archaeology in action, and in 2024 the site will be open to the public between 26 June and 16 August.

2004: Must Farm Bronze Age settlement, England, UK

Dr Colleen Morgan/Flickr/CC BY 2.0

Archaeologists dubbed a site adjacent to a quarry in the Cambridgeshire Fens the 'British Pompeii', after unearthing a large 3,000-year-old Late Bronze Age settlement. The site first came to experts’ attention when a series of wooden posts were spotted jutting out of the clay in 1999, but the first excavation didn’t happen until 2004. These early digs revealed a sword and spearheads, hinting at an early settlement. At this stage, researchers still had little idea of the scale of what lay beneath.

2004: Must Farm Bronze Age settlement, England, UK

Dr Colleen Morgan/Flickr/CC BY 2.0

Extensive excavations revealed more about what experts now deem the best-preserved Bronze Age settlement in Britain. From their multitude of discoveries, archaeologists were able to piece together the fate of this ancient village, and uncover some previously unknown truths about the Bronze Age people. Textiles, pottery and roof timbers (pictured) were all among the finds – the latter allowed experts to understand how homes in this period would have been built.

2004: Must Farm Bronze Age settlement, England, UK

Cmglee/Wikimedia Commons/CC BY-SA 4.0

Animal bones and fish scales (pictured) offered insights into the diet of the people who lived here, while fabrics gave experts a glimpse into the settlers’ clothing. Archaeologists also have enough information to deduce that the village was destroyed by a fire some six months after it was built – the village’s ruins sank into a nearby river, which is why they remain so beautifully preserved.

2008: Son Doong Cave, Vietnam

David A Knight/Shutterstock

This vast cave in Vietnam’s Phong Nha-Ke Bang National Park was first stumbled upon in 1990, by a logger named Ho Khanh who took refuge from a storm in its depths. Once the storm had passed, he reported his discovery to the British Caving Research Association (BCRA), who happened to be in Vietnam at the time. Unfortunately, he couldn’t manage to trace his steps back to the mysterious cavern. Then, almost two decades later, Ho Khanh rediscovered the cave's entrance while hunting and alerted the BCRA once more.

2008: Son Doong Cave, Vietnam

David A Knight/Shutterstock

In 2009, experts began exploring the newly uncovered cave and were awestruck by what they found. At more than 650 feet (200m) high and spooling out for more than 5.8 miles (9.4km), Son Doong Cave (meaning mountain river cave) was declared the largest cave complex ever discovered. They found stalagmites that towered to 80 feet (25m) and that the cave had a weather system all of its own. In 2013, Son Doong was opened to the public on guided expeditions. In 2019, divers discovered an underwater tunnel connecting it with another enormous cave, Hang Thung, making it even bigger than previously thought.

2009: the Staffordshire Hoard, England, UK

SHAUN CURRY/AFP/Getty Images

In July 2009 an amateur metal detectorist uncovered unfathomable ancient riches in a field in Lichfield. Known as the Staffordshire Hoard, the vast war stash was the largest collection of Anglo-Saxon gold and silver metalwork ever found, comprising over 4,000 items. A major research and conservation project took place from 2012 to 2016 to analyse the items which were buried in the Kingdom of Mercia in the 7th century. Most of the objects are gold and martial, once belonging to elite warriors, and were made between AD 570 and 650. The treasures are currently on display at the Potteries Museum and Art Gallery in Stoke.

2011: Sri Padmanabhaswamy Temple treasure, India

Alionabirukova/Shutterstock

With its elaborate exterior, the Sri Padmanabhaswamy Temple in Kerala is a majestic sight – yet this is just the tip of the iceberg. Buried deep within the Hindu temple, in a series of six vaults, are untold treasures said to be worth billions of dollars. The contents of one chamber, named Vault A, remained shrouded in mystery for years, but after a legal battle it was finally unsealed in 2011 so an inventory could be taken.

2011: Sri Padmanabhaswamy Temple treasure, India

Suronin/Shutterstock

Inside, it’s reported a dazzling array of gold, silver and jewels was discovered, including sparkling rubies, diamonds and an 18-foot (5.5m) gold chain studded with gems. A sixth chamber, Vault B, remains locked and the former royal family of Travancore (whose ancestors constructed the temple) is asking for it to remain that way, saying that opening it would be against tradition and faith. Legend dictates that a curse hangs over the tomb, meaning that terrible things would happen to anyone who unseals its doors.

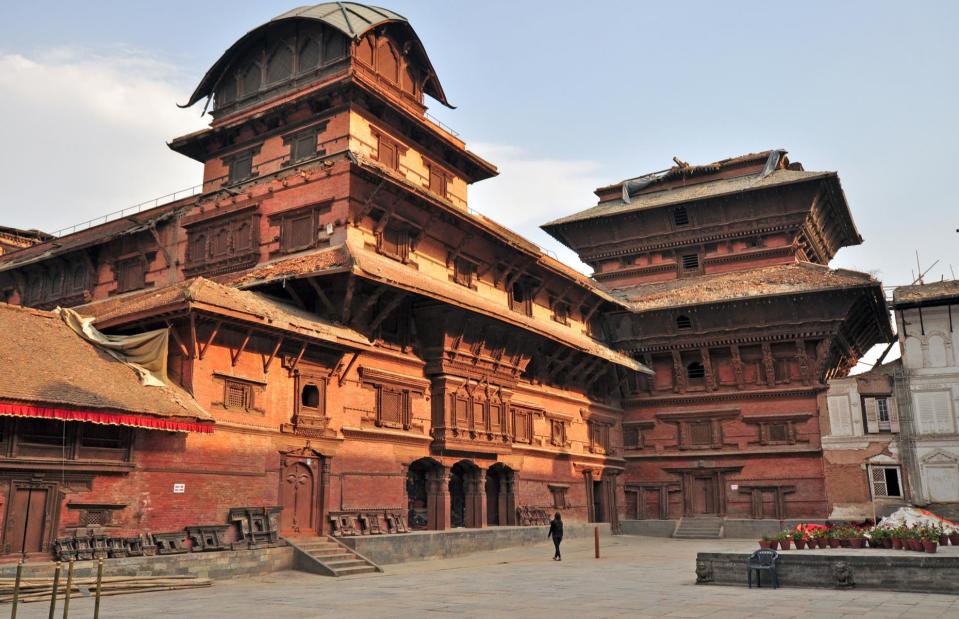

2011: Hanuman Dhoka Palace treasures, Nepal

WojtekChmielewski/Shutterstock

When labourers were renovating this former royal palace in 2011, they happened upon a treasure trove, tucked away in a storeroom underneath the building. Stuffed inside three boxes was a huge stash of gold and silver coins and ornaments, weighing in at around 300kg (661lbs). The hoard was most likely an offering to the gods and goddesses.

2012: Temple of the Night Sun, Guatemala

EvgenyDrokov/Shutterstock

A three-day trek from the Maya citadel of Tikal (pictured) lies El Zotz, an ancient city hidden in the dense rainforest. In 2012, a team uncovered an ornate pyramid there. It’s thought the structure, called the Temple of the Night Sun, dates from around AD 350, and that it was built for the body of a deceased king. In its heyday, it would have been bright red and visible for miles around – a powerful symbol of the king's dynasty.

2012: a secret rainforest, Mozambique

Landstat/Copernicus/Google Earth

Dr Julian Bayliss first spotted a rainforest right at the top of Mount Lico in northern Mozambique using Google Earth in 2012 (pictured). Though known locally, the mountain rainforest remained virtually untouched by humans due to its remote location. In 2017, Bayliss flew a drone over the peak and confirmed the forest's existence. Then in May 2018, he assembled a team to scale the mountain and explore the pristine forest. The expedition was a success and the team uncovered a string of new species from fish to frogs, including a previously undocumented breed of butterfly.

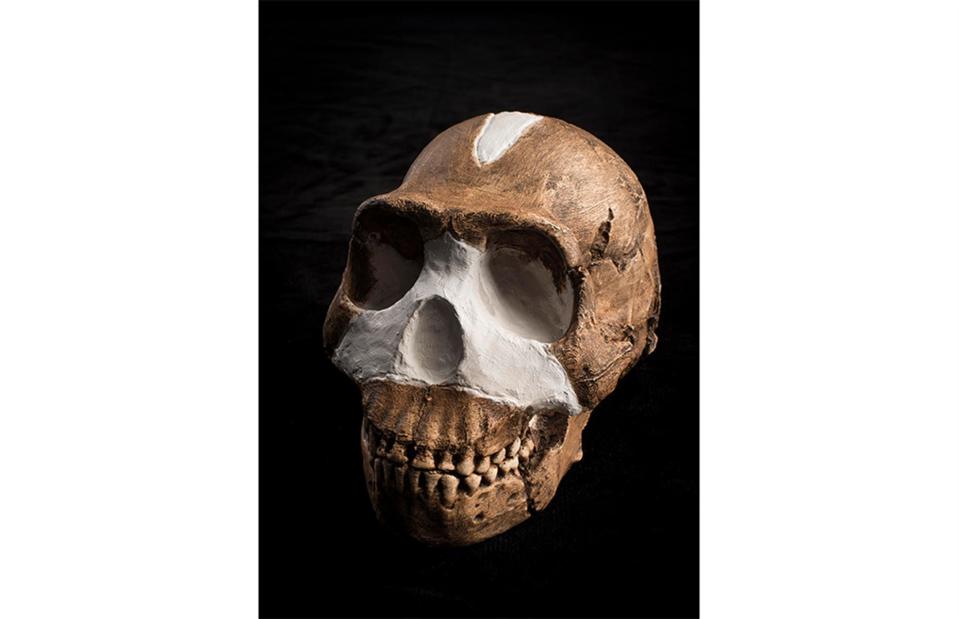

2013: Homo naledi, South Africa

Courtesy of John Hawks/Wits University

In 2013, a couple of cavers discovered a haul of more than 1,500 fossilised bones in a chamber deep in the Rising Star cave system in South Africa's Cradle of Humankind World Heritage Site. When the skeletons were eventually removed, it emerged they were in fact the remains of a previously undiscovered primitive species of human. The species, which was named Homo naledi in 2015, is thought to have had an ape-like torso, curved fingers and brains around a third of the size of ours.

2013: Homo naledi, South Africa

Courtesy of Wits University

Further analysis suggests this extinct species of primitive humans, whose remains have only been found in this cave system near Johannesburg, existed 236,000-335,000 years ago. Quite why the remains were so deep inside the caves is puzzling, but one theory proposes that Homo naledi used the caves as a place to deposit the dead.

2016: El Castillo’s hidden pyramid, Chichen Itza, Mexico

FerGregory/Shutterstock

With its 365 magnificent steps and imposing height, the four-sided El Castillo pyramid (or the Temple of Kukulcan) at the centre of the Chichen Itza archaeological site is one of Mexico’s biggest tourist draws. In 2016, archaeologists discovered the incredible ancient structure was hiding a secret. Already aware that a second pyramid lay hidden inside El Castillo's walls, experts performed scanning techniques and revealed a third.

2016: El Castillo’s hidden pyramid, Chichen Itza, Mexico

VictorTorres/Shutterstock

It’s thought this 'Russian doll' effect is down to the Maya temple being built in three marked phases. The new discovery, which is 33 feet (10m) high, was constructed between AD 550 and 800. The second was built between AD 850 and 1000 and the visible exterior pyramid between AD 1050 and 1300.

2016: a secret structure at Petra, Jordan

Pocholo Calapre/Shutterstock

Technology also helped researchers uncover a giant platform buried under the desert at the ancient city of Petra in Jordan. After poring over satellite and drone images, archaeologists noticed a large rectangular structure not far from the UNESCO World Heritage Site's famous Treasury (pictured). It’s thought that the mighty structure, which was once lined with columns, could have had a ceremonial purpose.

2017: Roman boxing gloves, England, UK

The Vindolanda Trust

Every year archaeologists at Vindolanda, a Roman archaeological site just south of Hadrian’s Wall in the north of England, conduct an excavation of a different section of the land and discover some incredible finds. In 2017, they found swords, writing tablets and shoes and, most impressive of all, a pair of leather Roman boxing gloves (pictured). These curious artefacts went on display in the Vindolanda Museum in February 2018. The museum says it will take another 150 years to complete excavations of the entire site.

2017: Roman 'horseshoes', England, UK

The Vindolanda Trust

Another, later dig at Vindolanda uncovered yet more riches. The most significant find was a set of rare iron 'hipposandals', a kind of historic horseshoe. Of the four hipposandals unearthed, only one was damaged – the others remained in perfect condition. The artefacts are now on display at the Roman Army Museum in Greenhead, Northumberland.

2017: Qalatga Darband, Iraqi Kurdistan

SAFIN HAMED/Getty Images

Thanks to declassified spy footage and drone photography, a lost city was unearthed in Iraqi Kurdistan. Built around 331 BC, the fortified city of Qalatga Darband is thought to have been established by Alexander the Great and is positioned on a strategically important route between Iran and Iraq.

2017: Qalatga Darband, Iraqi Kurdistan

SAFIN HAMED/Getty Images

The site was originally detected when experts watched declassified spy footage that was made public in 1996, but the area’s political volatility meant nothing could be done at first. In 2016 a team of Iraqi and British archaeologists, led by specialists from the British Museum, began excavating the area. In 2017, they began to uncover terracotta roof tiles and remains of statues that show Greco-Roman architectural styles. Further investigations are now underway at two nearby sites, including a fort that dates to the Assyrian Empire (9th to 7th centuries BC).

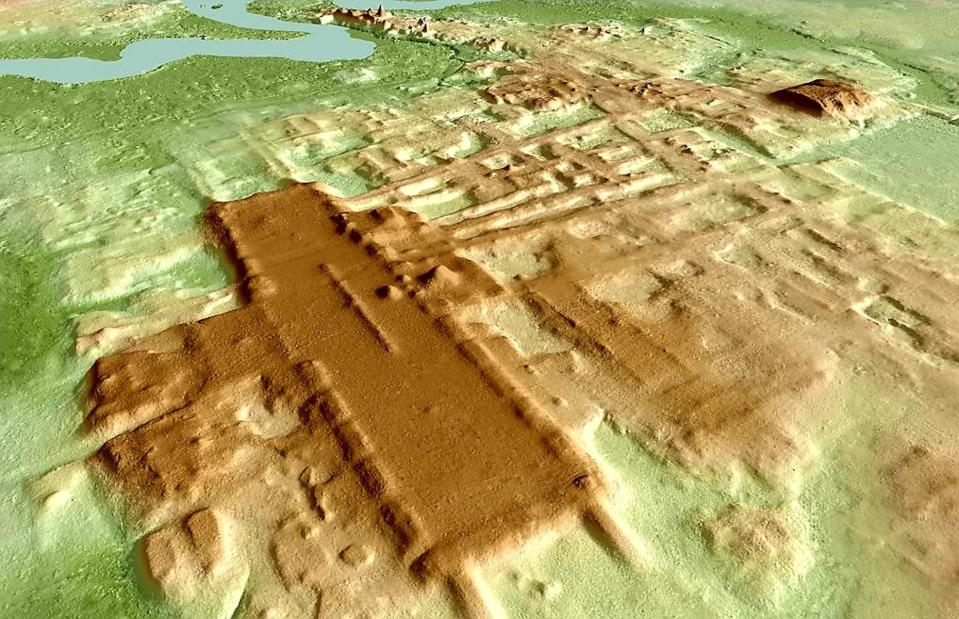

2018: Tikal's unknown treasures, Guatemala

WitR/Shutterstock

The Maya settlement of Tikal in northern Guatemala has been studied for decades, and it’s one of the best understood sites of its kind. Or so experts thought. In 2018, new technology called LIDAR (Light Detection and Ranging) allowed archaeologists to dig a little deeper. LIDAR involves lasers, which pierce through the forested land to the earth below. Based on how long it takes a beam to bounce back, scientists can map any hidden structures that exist beneath the ground. The findings were extraordinary.

2018: Tikal's unknown treasures, Guatemala

Nadine Folkertsma/Shutterstock

Studies revealed that Tikal is some four times bigger than experts originally thought. They also uncovered a central temple that was previously assumed to be a hill. It turned out to be a pyramid that was a smaller-scale replica of one in Teotihuacan, Mexico which suggested close ties between the two centres. Later excavations also confirmed the previously hidden buildings were raised using mud plaster, instead of the traditional Maya limestone.

2019: Homo luzonensis, Philippines

Noel CELIS/AFP/Getty Images

A previously unknown ancient human species was identified in 2019 after archaeologists found several teeth and small bones in a cave on Luzon, the largest island of the Philippines. It’s understood the small-bodied hominins lived there between 67,000 and 50,000 years ago. Curved finger and toe bones suggest climbing was still an important activity for this pre-human species.

2019: a 1,500-year old church, Israel

MENAHEM KAHANA/AFP/Getty Images

After a three-year excavation project, an ancient church was found in Beit Shemesh, around 19 miles (30km) west of Jerusalem, in October 2019. The incredibly opulent church, which had colourful and elaborate mosaics, was named the 'Church of the Glorious Martyr'. Archaeologists discovered this after an inscription dedicated to a 'glorious martyr', an unnamed VIP, was found at the 16,145-square-foot (1,500sqm) site.

2019: a 1,500-year old church, Israel

MENAHEM KAHANA/AFP/Getty Images

A Greek inscription was also revealed that thanked the Byzantine Emperor Tiberius II Constantine for funding the church’s expansion. Tiberius ruled between AD 578 and 582, around 100 years after the Western Roman Empire collapsed, but it’s likely the church was built a little earlier during the time of Emperor Justinian, who ruled from AD 527 to 565.

2019: a nobleman's tomb, Luxor, Egypt

AFP/Getty Images

April 2019 saw a new and intriguing discovery unveiled at the Draa Abul Naga necropolis in Luxor. Archaeologists uncovered a vast 3,500-year-old tomb which was opened to the public. Covering 4,860 square feet (450sqm), it is one of the largest ever discovered on the site. It has 18 entrances and is thought to have belonged to a nobleman known as Shedsu-Djehuty. He most likely served King Thutmose I as the royal master of seals. The tomb features colourful floor tiles and wall paintings depicting activities including boat making and hunting.

2020: Romulus's tomb, Rome, Italy

FILIPPO MONTEFORTE/AFP/Getty Images

Understandably, the legend of Rome’s founding by twin brothers Romulus and Remus has long been considered a tall story by historians. Discussions about the legend came to the fore once again with the discovery of a 6th century BC stone sarcophagus believed to be the tomb of Romulus, uncovered under Rome’s Forum in February 2020. However, on inspection, no bones were found inside. It’s thought it was a shrine dedicated to the fabled founding father of the Eternal City.

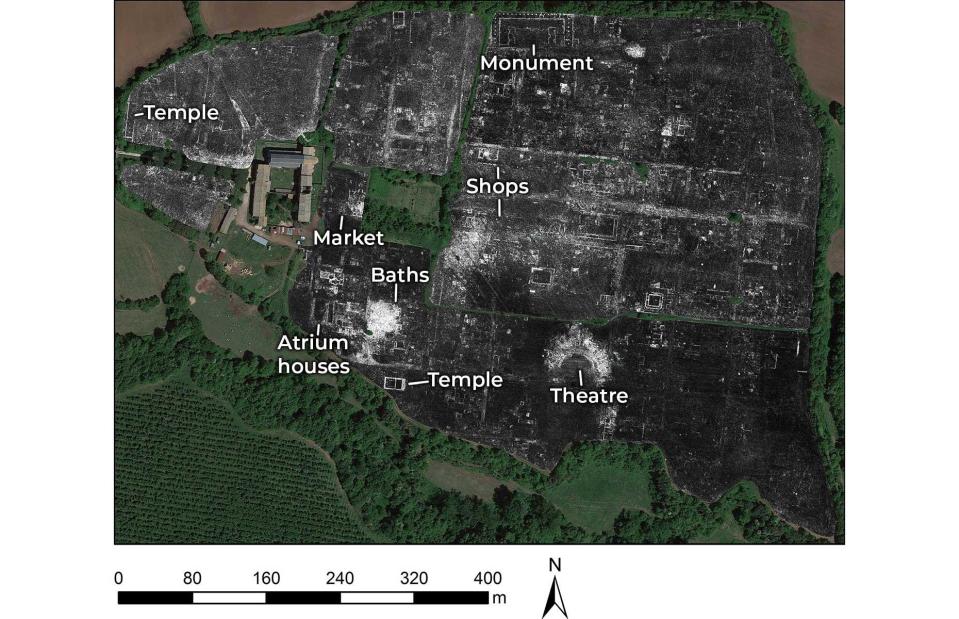

2020: secrets of Falerii Novi, Italy

Antiquity Journal/M Millett

Historians have long known about Falerii Novi, a buried Roman city just north of Rome, but it was thanks to a new mapping technique, advanced ground-penetrating radar (GPR), that more details were finally revealed. Academics from Ghent University in Belgium and the University of Cambridge surveyed the 30.5 hectares of land by towing the GPR equipment behind a quad bike. The images they took revealed astonishing specifics about the underground city that’s just under half the size of Pompeii.

2020: secrets of Falerii Novi, Italy

Google Earth/L. Verdonck

The technology revealed the Roman town, populated from 241 BC to around AD 700, had an architecturally sophisticated layout complete with a bath complex, theatre, temples and market building. It’s hoped the technique can help historians and archaeologists learn more about ancient places without the need for excavation, particularly for those that are large or beneath modern buildings.

2020: Roman mosaic, Italy

Comune di Negrar di Valpolicella/Facebook

While the remains of a Roman villa at this site in northeastern Italy’s Veneto region were initially discovered in 1887, it wasn’t until May 2020 after decades of searching that this colourful and intact mosaic was fully revealed. The well-preserved floor was found several feet beneath a row of vines along with the foundations of an 1,800-year-old villa, which had previously lain hidden underneath the vineyard better known for its Valpolicella wines.

2020: Aguada Fenix, Mexico

Alfonsobouchot/Wikimedia Commons/CC BY-SA 4.0

The oldest and largest known Maya-built structure was discovered in Mexico’s Tabasco state using remote-sensing aerial technology in 2020. Following excavations, archaeologists radiocarbon-dated the site and estimated it was built between 1000 and 800 BC. It’s thought the large rectangular platform, which was made of clay and earth, was used for rituals. Known as Aguada Fenix, the previously unknown site sits near the northwestern border with Guatemala.

2020: prehistoric monument, England, UK

Chris Gorman/Getty Images

The most famous prehistoric monument in Europe, Stonehenge, was erected in the late Neolithic period on Salisbury Plain in around 2500 BC. The mystery of how and why the enormous sarsen stones and smaller bluestones were transported and erected here has fascinated people for centuries. But in June 2020 it was revealed that next to Stonehenge another intriguing circular monument, an enormous ring of ancient pits, had been discovered using remote sensing technology and sampling.

2020: prehistoric monument, England, UK

Andrew Matthews/PA Archive/PA Images

The new prehistoric circle was discovered at Durrington Walls, just under two miles (3km) from Stonehenge, and consists of 20 huge shafts, more than 33 feet (10m) in diameter and 16.4 feet (5m) deep. These structures would have been an extraordinary engineering feat and seem to have been designed to create a circle around Durrington Walls henge (pictured here) and Woodhenge, another smaller prehistoric circle to the south.

2020: prehistoric monument, England, UK

English Heritage/Heritage Images/Getty Images

Radiocarbon dating revealed the shafts to be 4,500 years old and from the Neolithic period. It's likely that the same people who constructed Stonehenge built the shafts at Durrington Walls, which is now the largest prehistoric site discovered to date in the UK and where the builders of Stonehenge lived. This reconstruction shows the settlement in midwinter, with timber monuments (southern circle and northern circle), houses and western enclosures in the foreground.

2021: a lost city, Egypt

Mahmoud Khaled/Getty Images

Archaeologist Dr Zahi Hawass and his team began searching for a temple near the city of Luxor, on the west bank of the Nile, in September 2020. And they got a little more than they bargained for. On 8 April 2021, they announced the discovery of an entire 3,000-year-old city which had been buried under sand. Known as Rise of Aten, it’s thought to be the largest ancient metropolis ever uncovered in Egypt – the significance of the find has been compared to the discovery of Tutankhamun's tomb.

2021: a lost city, Egypt

KHALED DESOUKI/AFP/Getty Images

Described as a "lost golden city", it dates back to the reign of Amenhotep III, between 1391 and 1353 BC, which was one of the most affluent periods in Egyptian history. According to the archaeologists who found it, the former town is remarkably well preserved, with rooms filled with objects including clay pots, tools for spinning and weaving, rings and scarabs. Thanks to mud bricks bearing the seals of King Amenhotep III's cartouche, the archaeologists were able to date the settlement to this period.

2021: new tombs at Saqqara, Egypt

KHALED DESOUKI/AFP/Getty Images

The Egyptian government announced a series of significant new discoveries at Saqqara, a vast ancient burial ground south of Cairo known for its stepped pyramid, at the beginning of 2021. This included the incredible discovery of a previously unknown queen. Archaeologists unearthed the funerary temple of Queen Nearit, who was one of King Teti's wives. It was discovered near the pyramid of Teti, the first pharaoh of the Sixth Dynasty who ruled between 2323 and 2150 BC.

2021: new tombs at Saqqara, Egypt

AHMED HASAN/AFP/Getty Images

Also found at the vast necropolis of Saqqara were 50 wooden sarcophagi (coffins), dating back to the New Kingdom period (16th-11th century BC) which were found in 52 burial shafts. Another of the most dazzling discoveries at the burial ground for the ancient capital, Memphis, were 100 ornately painted wooden coffins, some with mummies and artefacts, including amulets (good luck pendants), funeral statues and masks, that archaeologists discovered in November 2020 (pictured).

2021: Vindelev Hoard, Denmark

Vejlemuseerne/Facebook

First-time detectorist Ole Ginnerup Schytz literally struck gold in September 2021 when he discovered a hoard of Iron Age treasure in a field in Vindelev – at almost a kilo it is the largest ever found in Denmark. The pre-Viking treasure, which contained huge gold medallions, coins and jewellery has since been dated back to the mid-6th century by experts at the Vejle Museum in Jutland, who carried out the excavation after Ole's discovery. They believe it was buried by an Iron Age chieftain under a longhouse to either keep it safe in the event of war or as a sacrifice to the gods.

2021: Vindelev Hoard, Denmark

Konserveringscenter Vejle/Facebook

Now known as the Vindelev Hoard, the stunning treasure suggests that the area was a powerful centre in the late Iron Age and one that had traded with other countries for some time. Among the gold was a much older coin from the Roman Empire, dating back to the time of Emperor Constantine the Great (AD 285-337), suggesting countries were closely connected through both war and trade.

2021: Ancient winery, Israel

MENAHEM KAHANA/AFP/Getty Images

A sprawling 1,500-year-old wine-making complex was unearthed by archaeologists working in Yavne in central Israel in 2021. It gives incredible insights into the role wine played in Byzantine society and beyond. Consisting of five wine presses and four large warehouses, the winery was capable of making two million litres of wine a year. The team also unearthed Gaza jars, used for wine storage in the region, and kilns for firing the clay vessels.

2021: Ancient winery, Israel

MENAHEM KAHANA/AFP/Getty Images

The sophisticated complex, thought to have been the largest in the world at the time, would have made a prestige white wine known as Gaza wine or Ashkelon. It would have been consumed by the local community, as a safer alternative to water, as well as exported. According to the Israel Antiquities Authority, the incredible find confirms that the region was at the centre of a flourishing wine trade with wines from the Yavne factory exported to Egypt, Turkey and Greece, as well as possibly southern Italy.

2022: Roman floor mosaic, London, England, UK

Andy Chopping/MOLA

Excavated as part of a wider regeneration of the Southwark area in London, archaeologists from the Museum of London Archaeology have uncovered an incredibly well-preserved Roman mosaic that once decorated the floor of a dining room. The largest area of Roman mosaic found in London for over 50 years, it features a highly intricate pattern that includes lotus flowers, two interlaced loops, known as Solomon's knot, and bands of intertwining strands called guilloche.

2022: Roman floor mosaic, London, England, UK

Andy Chopping/MOLA

The largest of the mosaic's panels can be dated to the late 2nd to early 3rd centuries and formed the floor of a dining room in a Roman mansio – a hotel of sorts that offered accommodation, stabling and dining facilities for Roman couriers and officials travelling to and from Londinium (Roman London). Given the size of the dining room and its lavish decoration, it is believed that only high-ranking officers and their guests would have used this space.

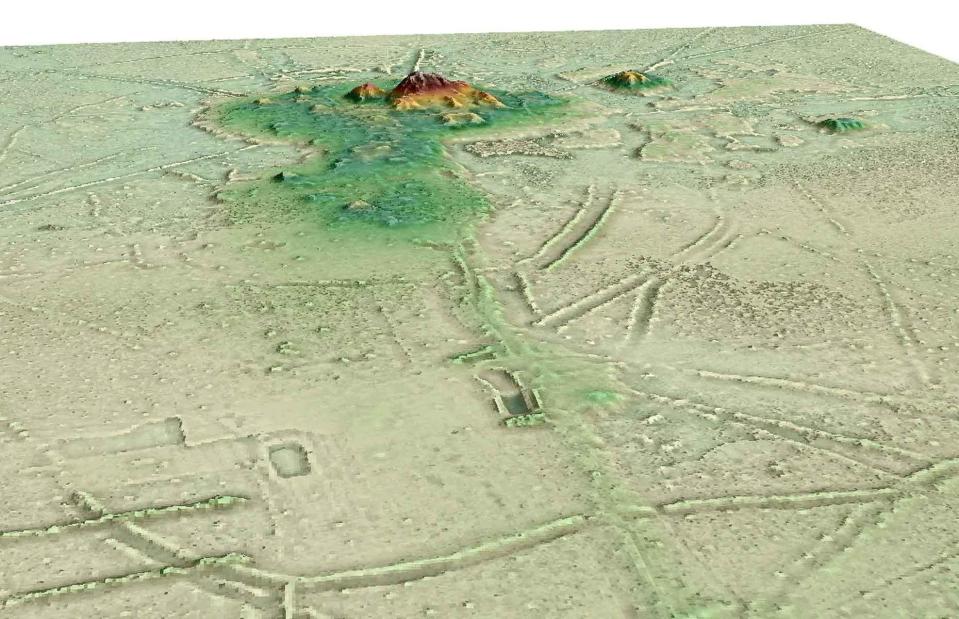

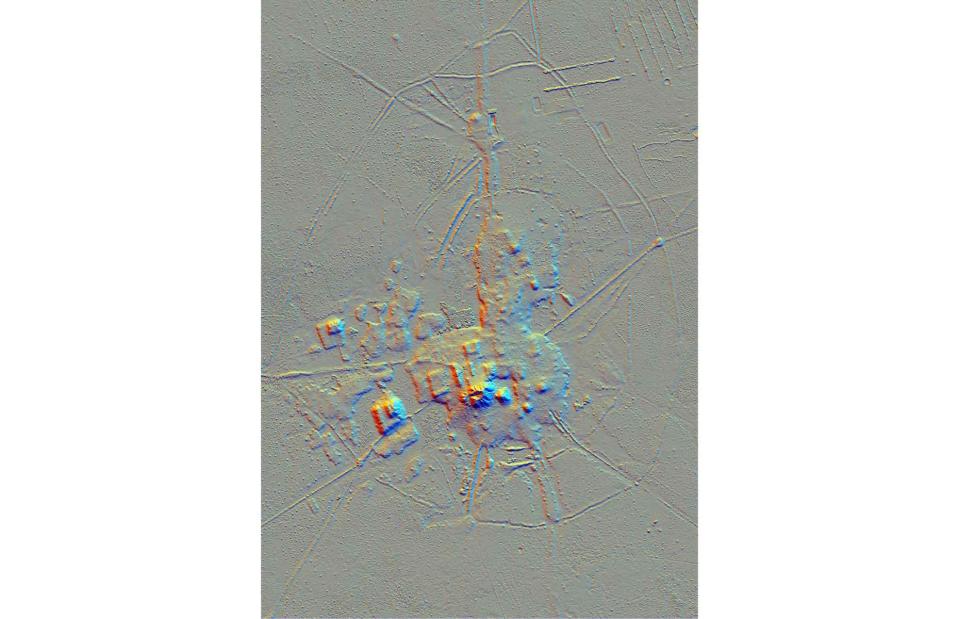

2022: Lost Amazonian cities, Bolivia

Source: H. Prumers/DAI

Researchers from the German Archaeological Institute, Planning of the Plurinational State of Bolivia and universities of Bonn and Exeter recently made a fascinating discovery. Using LIDAR technology (lasers) they located lost Amazonian cities in the Llanos de Mojos forest in Bolivia. Built by the Casarabe communities between AD 500 and 1400, the cities include U-shaped structures, rectangular platform mounds and 69-foot-tall (21m) conical pyramids. With the space covering the equivalent of 30 football pitches, the discovery disproves previous theories that this part of the tropical forest was uninhabitable.

2022: Lost Amazonian cities, Bolivia

Source: H. Prumers/DAI

Dense vegetation previously hid these settlements and prevented researchers from finding the monumental structures, but experts uncovered them by using LIDAR technology in the Amazon for the very first time. By attaching the laser scanner to a helicopter, they were able to produce these images (pictured) revealing the architecture and layout of the once-lost cities.

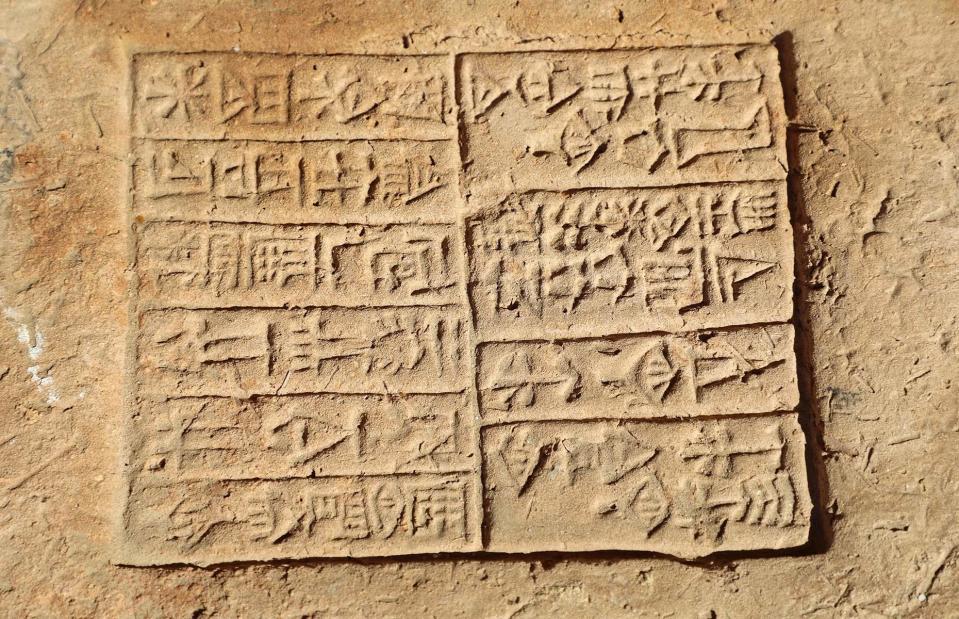

2023: Lord Palace of the Kings, Iraq

ASAAD NIAZI/Getty Images

This ultra-ancient palace was such a staggering find when it first emerged from the sand in 2022, that the project's lead archaeologist was accused of "making it up". Found in modern-day Tello in southern Iraq, the Lord Palace of the Kings stood above the ancient Sumerian city of Girsu more than 4,500 years ago, and was previously only known through fragmented inscriptions discovered in the surrounding area. The Sumerians were one of humankind's first known civilisations, and their 4th-millennium-BC city states produced the first written script, the first legal codes and the first ever examples of brewed beer.

2023: Lord Palace of the Kings, Iraq

ASAAD NIAZI/Getty Images

The work of the Girsu Project, an archaeological collaboration led by the British Museum, the palace is now mostly mud-brick walls, earthworks and foundations, though 200 cuneiform tablets have also been discovered bearing various administrative records. The director of the British Museum, Hartwig Fischer, called the site "one of the most fascinating I've ever visited". "The discovery holds enormous potential for our understanding of this important civilisation," he continued, "shedding light on the past and informing the future.

2024: Saxon ruins, London, England, UK

National Gallery/Archaeology South-East

It’s not always new technology that uncovers exciting new archaeological discoveries. Excavations at London’s National Gallery, part of a broad redevelopment project that's part of the gallery's bicentenary celebrations, unearthed the remains of an old Saxon town. While such discoveries are not uncommon in London, these ruins suggest that the settlement of Lundenwic – as London was known in Saxon times – was much larger than first believed.

2024: Saxon ruins, London, England, UK

National Gallery/Archaeology South-East

Excavators from Archaeology South-East, part of the UCL Institute of Archaeology, unearthed a hearth, postholes, stakeholes, pits, ditches and levelling deposits, as well as a treasure trove of Saxon-era artefacts. It was the discovery of a reworked fence line, however, that caused the most excitement. "The evidence suggests the urban centre of Lundenwic extended further west than originally thought", explained excavation leader Stephen White.

Now check out the most incredible ancient discoveries uncovered recently