Extraordinary photos show how the world has ACTUALLY changed

All change

Bettmann Archive/Getty Images | pisaphotography/Shutterstock

They say that the Age of Discovery is never over when you are the discoverer. But there’s no denying that the world we live in – and its most famous sights, attractions and landmarks – are constantly changing. Sometimes for the better, sometimes for worse.

Here's a selection of 'then’ and 'now' images that show just how dramatic those changes have been...

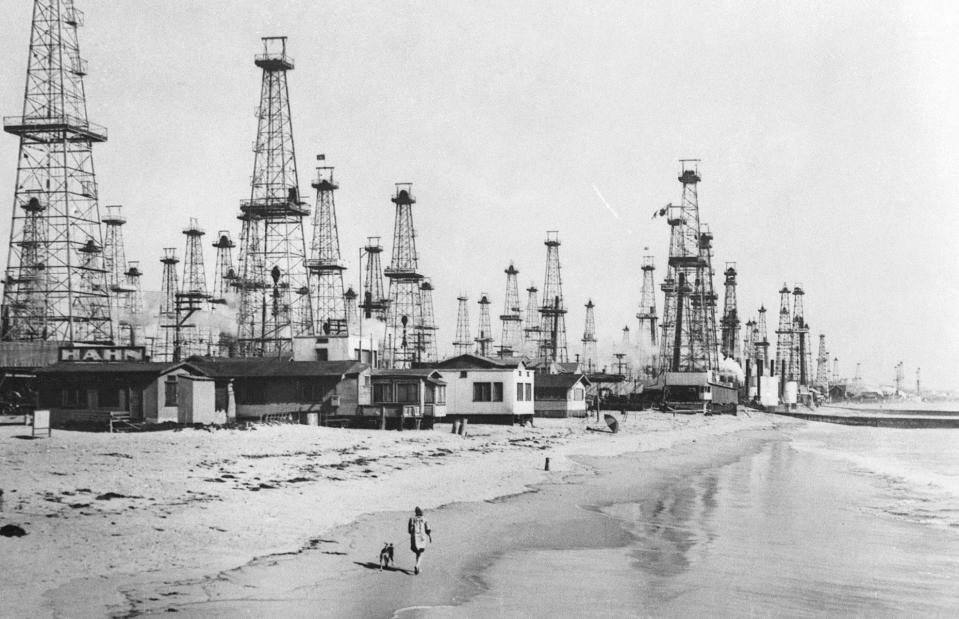

Then: Venice Beach, California, USA

Hulton-Deutsch Collection/CORBIS/Corbis via Getty Image

In 1929, at the height of the Great Depression, one of California’s most famous beaches became the centre of an unlikely oil boom. The Ohio Oil Company struck oil just at the back of Venice Beach and by 1931 it was the 4th most productive oil field in California.

When this photo was taken in 1931, there were 340 wells in use and a forest of derricks where palm trees had once stood. By 1932 the wells were tapped, leaving the surrounding lagoons and canals thick with sludge and the beach an unsightly mess.

Now: Venice Beach, California, USA

FREDERIC J. BROWN/AFP via Getty Images

Today all that remains of the Venice Beach oil boom is a lone oil derrick camouflaged to look like a lighthouse. Palm trees have once again replaced the derricks and the world-famous boardwalk is full of funky shops, street performers and colourful murals and featured in the recent Barbie movie.

That same breakwater in the first image is now a popular surfing spot, pictured here, ironically as surfers wait for waves on Earth Day on 22 April 2023.

Then: Bennelong Point, Sydney, NSW, Australia

EMU history/Alamy Stock Photo

Bennelong Point juts out into Sydney Harbour on the eastern side of Circular Quay. It was once a tidal island and was named after Bennelong, an Aboriginal man used by the British as a cultural interlocutor in the 1790s, who lived in a hut here.

At times it has been the site of a fort, built to protect the harbour from invasion (pictured here in 1873) and later as a rather fancy tram depot.

Now: Bennelong Point, Sydney, NSW, Australia

Jeffrey Isaac Greenberg 7+/Alamy Stock Photo

The tram depot was closed in 1953 and demolished in 1958 to make way for an audacious new building – an opera house, designed by Danish architect, Jorn Utzon. With its soaring iconic sails, the Sydney Opera House was quite unlike any other building in Australia, and even the world, and proved troublesome to build.

Utzon rancorously resigned from the project in 1966 and by the time it was finished in 1973 it was 10 years overdue and 14 times over budget. Sydneysiders will happily tell you that their iconic architectural masterpiece was worth every cent.

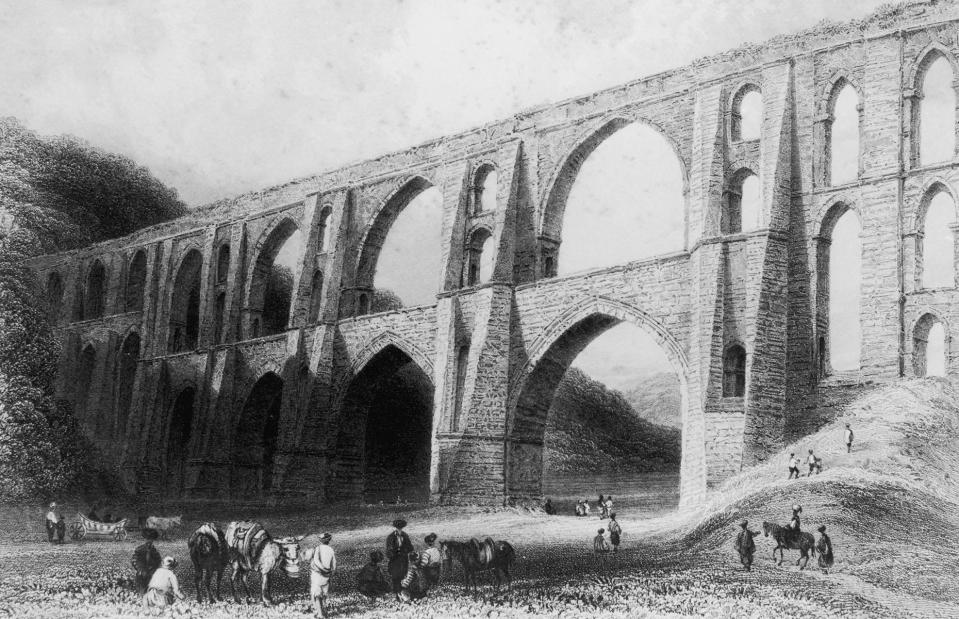

Then: Valens Aqueduct, Istanbul, Turkey

Hulton Archive/Getty Images

The Valens Aqueduct in Istanbul was part of an elaborate system that brought water from the north of the city along 155 miles (250km) of water channels and across 30 bridges to fill more than 100 cisterns within the city walls. Commissioned by Emperor Valens and completed in AD 378, it is regarded as one of the greatest hydraulic engineering achievements of ancient times.

This illustration of the aqueduct by artist R. Wallis dates from 1840.

Now: Valens Aqueduct, Istanbul, Turkey

Ayhan Altun/Alamy Stock Photo

The Valens Aqueduct was repaired and restored many times both in Byzantine and Ottoman periods and continued to bring water to the city for almost 1,400 years, right up until the 18th century. By the 20th century Istanbul’s city limits had sprawled up to the aqueduct and beyond.

In 1953 Ataturk Boulevard was built to connect the area to other parts of the city, with lanes passing through the aqueduct’s limestone arches. Despite Istanbul’s notoriously congested traffic, Valens Aqueduct remains one of the city’s most distinctive landmarks.

Then: Hong Kong Harbour

Pix/Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images

When Britain acquired Hong Kong Island under the Treaty of Nanjing in 1842, it was little more than a sleepy fishing village. But the British saw great commercial potential in Hong Kong’s fine natural harbour and its proximity to the Chinese mainland.

And even though there were signs of substantial growth in this photo taken in 1930, a more startling transformation was yet to come.

Now: Hong Kong Harbour

YIUCHEUNG/Shutterstock

The rise of the Communist Party after the Second World War saw a flight of capital entrepreneurial talent out of China and into Hong Kong. It turned Hong Kong into an international financial centre and spurred the colony's industrial development.

It created the dynamic modern city we know today, a place where East meets West to do business, and reflected in a harbourfront skyline, bristling with skyscrapers.

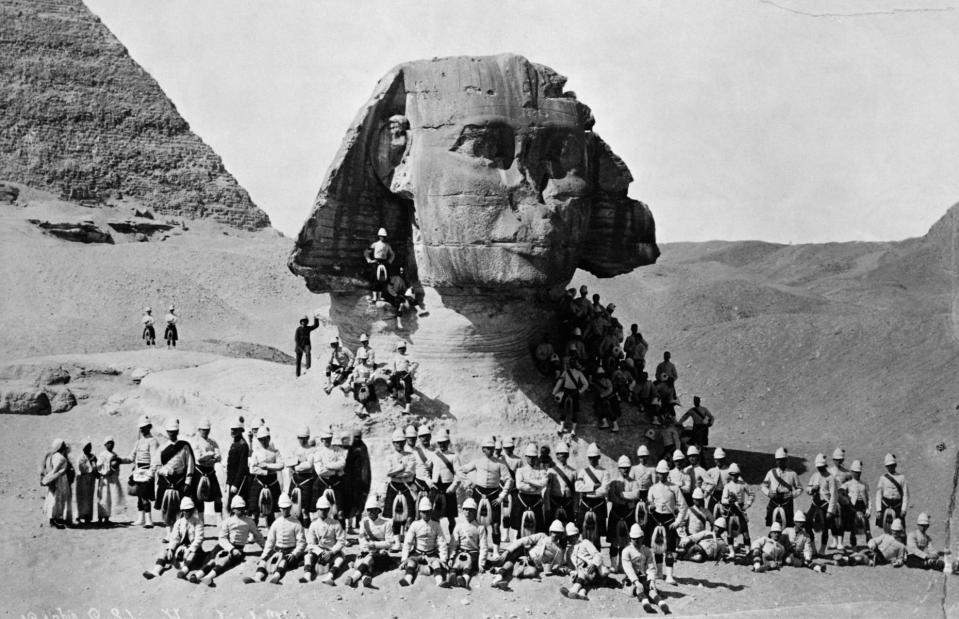

Then: Great Sphinx of Giza, Egypt

Hulton-Deutsch Collection/CORBIS/Corbis via Getty Images

The Great Sphinx of Giza sculpture is arguably one of the world's most famous landmarks. At about 240 feet (73m) long and 66 feet (20m) high, it is enormous. And old too, built by King Khafre, who ruled some 4,500 years ago.

But after the fall of the pharaohs, it was largely lost in time, buried up to its shoulders for centuries. It was still partially entombed in sand when this photo was taken in 1882, showing victorious British troops swarming the monument after the Battle of Tel-El-Kebir.

Now: Great Sphinx of Giza, Egypt

Daily Travel Photos/Shutterstock

More and more of the Sphinx was revealed over the intervening decades with the Egyptian archaeologist Selim Hassan finally 'freeing' the statue from the sand in the late 1930s. In 1989 a Sphinx committee was established to oversee its restoration and maintenance.

Today it sits proud and fully exposed in front of the Pyramids of Giza, a guardian waiting patiently, like the rest of us, for the new Grand Egyptian Museum to open nearby.

Then: India Gate, New Delhi, India

saiko3p/Shutterstock

Often described as India’s Arc de Triomphe, the 138-feet-high (42m) sandstone monument located at the eastern end of the Rajpath in New Delhi serves the same purpose: to honour fallen soldiers. It was built by order of the Imperial War Graves Commission to stand as a memorial to 74,187 soldiers of the Indian Army who died between 1914 and 1921 in the First World War.

Its English architect Sir Edwin Lutyens famously refused to incorporate Asian motifs in his design, feeling they would detract from its simple classic lines.

Now: India Gate, New Delhi, India

Arrush Chopra/Shutterstock

While the monument itself hasn’t changed, the air quality of the Indian capital has. As the city’s population has exploded to over 33 million people, its problem with pollution has too. New Delhi is regularly ranked as the most polluted city in the world, with experts claiming that it has shortened the lives of locals by a staggering 11.9 years.

The post-monsoon season from October to December is the worst, when the city experiences a 'pollution bomb': seen here in this sobering image of India Gate under a thick blanket of smog.

Then: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil

The Print Collector/Getty Images

As this 1895 image shows, the vista across Rio from Corcovado to Sugarloaf Mountain has always been gorgeous. It’s a stunning panorama of beach-lined bays, forested peaks, islands and the Atlantic Ocean.

The harbour here is as big as it is beautiful, recognised as the largest in the world according to the amount of water it holds. As the locals like to say, “God made the world in six days and on the seventh, he concentrated on Rio.”

Now: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil

marchello74/Shutterstock

The city embellished God’s handiwork with the unveiling of the world-famous Christ the Redeemer statue in 1931. Perched on the summit of Mount Corcovado, looking out across the city with arms outstretched, the colossal 98-feet-tall (30m) statue is the cherry on top of an already gorgeous cake.

It is the largest Art Deco statue in the world and an instantly recognisable symbol of not just Rio but Brazil itself. Perfection, it seems, can be improved upon.

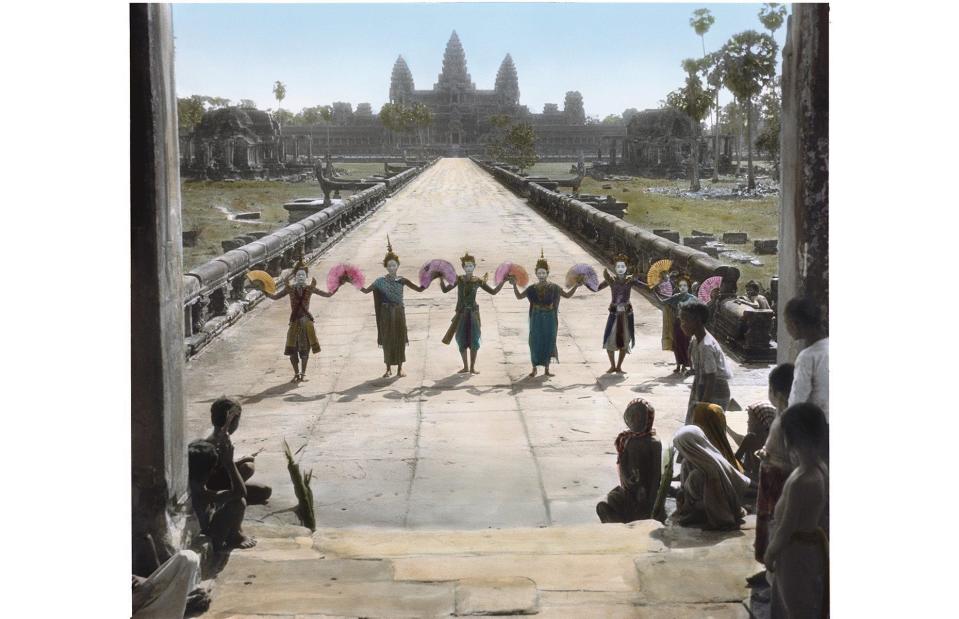

Then: Angkor Wat, Siem Reap, Cambodia

Archive Farms/Getty Images

Angkor Wat, in northwest Cambodia, is the largest religious building in the world and the ultimate expression of Khmer architectural ingenuity. Initially built as a Hindu temple complex in the first half of the 12th century, it was converted to a place of Buddhist worship shortly after.

It didn’t become known to the West until the 1840s when French explorer Henri Mouhot described it as "grander than anything left to us by Greece or Rome." But visitors like these, pictured, greeted by traditional dancers in 1925, were few and far between.

Now: Angkor Wat, Siem Reap, Cambodia

TANG CHHIN SOTHY/Getty Images

Cambodia’s troubled history meant that the site spent much of the 20th century unvisited and unknown. Efforts to restore Angkor Wat were slow and haphazard and ground to a halt during the 1970s when the Khmer Rouge dictator Pol Pot ruled the country and exterminated the professional and technical classes.

But when peace came and the site was designated by UNESCO in 1992, restoration efforts increased tenfold. More than 2.64 million people visited the site in the first seven months of 2023 alone.

Then: Dubai, United Arab Emirates

NASSER YOUNES/AFP via Getty Images

After it was established in the early 18th century, Dubai spent much of its history as a sleepy fishing village. But the discovery of oil in the region in the 1960s changed all that. Dubai's growth was turbocharged.

By the beginning of the new millennium an artificial canal city known as Dubai Marina was being created along the Persian Gulf shoreline. Here we see it in 2003 in the early days of its construction.

Now: Dubai, United Arab Emirates

Ashraf Jandali /Shutterstock

Just over 20 years later, the transformation is staggering. The emerald-green canals of this waterfront city are framed by some of the tallest – not to mention some of the most architecturally impressive – residential towers in the world, including the twisty 75-storey high Cayan Tower (pictured).

Popular with visitors, young professionals and families alike, Dubai Marina was recently voted one of the 50 coolest neighbourhoods in the world by Time Out.

Then: Times Square, New York, USA

Bettmann Archive/Getty Images

When this photo was taken around 1900, Times Square was still called Longacre Square. It was named after Long Acre in London and for most of the 19th century it served as the centre of New York’s horse carriage industry.

It was also where William Henry Vanderbilt ran the American Horse Exchange. But as plans to build a subway station here emerged and The New York Times moved into the building now known as One Times Square in 1904, the name was changed and the character of the area began to change too.

Now: Times Square, New York, USA

pisaphotography/Shutterstock

Since then, Times Square has grown dramatically, becoming a hub for theatres, dance halls and upscale hotels. It has survived the Great Depression and two World Wars and continues to attract visitors from around America and the world.

It is also where New Yorkers gather to ring in the New Year. The world-famous ball drop dates back to 1907, when a wood-and-iron globe decorated with 100 light bulbs was lowered from the top of a flagpole.

Today the Times Square Ball is 12 feet (3.7m) in diameter, weighs 11,875 pounds (5,386kg) and is covered in 2,688 crystal triangles.

Then: Aral Sea, Kazakhstan

David Turnley/Corbis/VCG via Getty Image

The Aral Sea in the former Soviet Union was once the fourth largest lake in the world, with its water lapping the shores of all five Central Asian republics – Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan. Fed by the mighty Syr Darya and the Amu Darya rivers, it covered a staggering 26,300 square miles (68,000sq km), a vastness that saw it referred to as a sea rather than a lake.

Then, in 1960, the Soviet government diverted the rivers to irrigate cotton farms across the arid plains of Central Asia, and the Aral Sea began to shrink dramatically.

Now: Aral Sea, Kazakhstan

Theodore Kaye/Alamy Stock Photo

Although irrigation made the desert bloom, it devastated the Aral Sea. The lake began to shrink dramatically, leaving vessels stranded where they once docked. The fishing industry collapsed. The increasingly salty water became polluted with fertiliser and pesticides.

And the dust from the exposed lakebed, contaminated with agricultural chemicals, became a public health hazard. An $86 million (£67m) project, funded by the Kazakh government and the World Bank, has helped recover parts of the North Aral Sea, but much of the damage remains undone.

Then: Stonehenge, England, UK

English Heritage/Heritage Images/Getty Images

Stonehenge is thought to date back 4,500 years and has changed very little over the following centuries. For much of that time it sat silent and brooding, surrounded by grazing sheep, on a plain in Wiltshire, southwest England.

This photo from 1901 was taken during a landmark dig and restoration project overseen by renowned British engineer William Gowland. Using techniques he’d learned in Japan, he was able to determine that Stonehenge was a Neolithic (pre-metal) monument, making its architectural sophistication even more astounding.

Now: Stonehenge, England, UK

JaamSaqi/Shutterstock

More than 100 years later, Gowland's wooden frames and equipment are long gone. Stonehenge remains unchanged but our understanding of its history and purpose have. Recent excavations have turned up relics including deer antlers, pottery and burial sites.

And new evidence has linked Stonehenge to a site called Waun Mawn in Pembrokeshire. Archaeologists now believe that the monument was erected in Wales before being transported to its current site on the Salisbury Plain.

Then: Expedition to Antarctica

The Print Collector/Alamy Stock Photo

Antarctica was the last continent to be discovered and its early exploration at the turn of the 20th century was fraught with peril. The wooden sailing ships of the time risked being crushed by sea ice.

Sailors’ clothes were rudimentary and made from fur and wool. And when the food brought along for the expedition inevitably ran out, sailors had to eat penguins, seals and seaweed.

This photo was taken during the Nimrod expedition of 1907–1909 and the man you can see would've had to row a small boat in sub-zero conditions to get to shore.

Then: Expedition to Antarctica

Eleanor Scriven/Shutterstock

Today luxury cruise ships make the same journey that took early Antarctic explorers months in a matter of days. Sea ice poses no threat to their reinforced steel hulls and modern-day expeditioners dine on delights such as honey-soy glazed salmon and crisp green salads.

They are ferried ashore by motorised zodiac boats wearing the latest hi-tech gear. Some even take a polar plunge, a quick dip in the freezing Antarctic waters – something that would have resulted in near certain death for early explorers.

Then: Arc de Triomphe, Paris, France

Hulton Archive/Getty Images

The horror and destruction of war has always had a terrible impact on people and places. This photo was taken in 1871 near the end of the Siege of Paris in the Franco-Prussian War.

The Germans bombarded the city for 23 days, firing more than 12,000 shells and killing at least 400 people. Here the Arc de Triomphe stands as a mournful witness to the destruction wrought along the Avenue de la Grande Armee.

Now: Arc de Triomphe, Paris, France

Yuri Turkov/Shutterstock

Today the tree-lined avenue is one of the busiest parts of Paris and shows no scars from the battering it took during the devastating siege or by bombing during both the First and Second World Wars. Instead, office workers and visitors alike gather here to enjoy the area's bustling shops, bars and restaurants.

Then: Tikal, Guatemala

Alfred Percival Maudslay/Wikimedia Commons/CC0

Tikal is a complex of Mayan ruins deep in the rainforests of northern Guatemala that date back to 300 BC. It was one of the most important cities in the Mayan empire until warfare, drought and crop failure sealed its decline.

It was quickly reclaimed by the jungle and lost to the world altogether until British explorer Alfred Maudslay began mapping and excavating the site during the 1880s. This early photograph of the site, snapped around 1882, shows the breathtaking ruins choked by vegetation and littered with fallen trees.

Now: Tikal, Guatemala

WitR/Shutterstock

Today the ruins are a UNESCO World Heritage Site and part of the Tikal National Park. The iconic stone pyramids are surrounded by thick jungle that echoes with the primeval cries of howler monkeys and the chattering of birds.

At times it feels like you are on the site of an Indiana Jones movie, especially if you stay overnight at the Jungle Lodge in quarters that were built especially for archaeologists from the University of Pennsylvania who helped excavate the site.

Then: Michigan Central Station, Detroit, USA

MichaelAnthonyPhotos/Shutterstock

Nothing symbolised the grandiose rise and spectacular fall of the US city of Detroit than its main railway station, Michigan Central. For 75 years its grand marble hall and vaulted 54-foot (16m) ceilings echoed with the sound of a city on the move.

Then the city fell on hard times and Michigan Central did too. The last train left on 5 January 1988 and the vandals and thieves moved in. Abandoned and neglected, it seemed like only a matter of time before the 'Temple of Transportation' could be demolished and lost forever.

Michigan Central Station, Detroit, USA

Stephen McGee/Visit Detroit

But like Detroit itself, Michigan Central Station is set to rise like a phoenix from the ashes, this time as the headquarters of the Ford Motor Company’s autonomous vehicle team, responsible for developing, testing and launching new urban transportation solutions. Ford purchased the site back in 2018 and spent the last six years renovating the building, using 3D printing to recreate the missing pieces that used to adorn the building and bring it back to its former glory.

The main area will always be open to the public.

Then: Table Mountain, Cape Town, South Africa

Print Collector/Getty Images

The sight of Table Mountain has always been inspiring. For sailors rounding the Cape of Good Hope in the 18th and 19th century it was a sign that fresh provisions and a rowdy night or two in a tavern were close at hand. For Nelson Mandela and other prisoners on Robben Island it was a beacon of hope, a reminder of the mainland to which one day they would return.

The flat-topped peak was designated a protected area in 1939, 43 years after this photo was taken in 1896.

Now: Table Mountain, Cape Town, South Africa

Arnold.Petersen/Shutterstock

Table Mountain is so monumental that the development that has occurred in Cape Town over the intervening years has only served to emphasise its immutable grandeur. The city’s tallest building now tops 448 feet (136.4m). The population is fast approaching five million.

But Table Mountain never changes. It remains vast and unknowable, with 52 tourists rescued from its flat top in 2022 alone.

Then: Miami Beach, Florida, USA

Pictorial Parade/Getty Images

From uninhabited sandbar and mangroves in the 1900s to a glamorous beach resort and thriving city by the 1910s, the transformation of Miami Beach is one of the most amazing in US real estate history. Growth was turbocharged even further when a wooden bridge was built to connect to the young city of Miami across Biscayne Bay.

And by the 1920s this burgeoning district of beachside hotels and casinos came to represent the height of glamour.

Now: Miami Beach, Florida, USA

felix mizioznikov/Alamy Stock Photo

There is no denying that Miami Beach has had its ups and downs over the years. The Great Depression and a major hurricane which hit the barrier island in 1926 had a devastating effect on Miami Beach's tourism industry.

The development of South Beach in the 1930s saw it bounce back, but by the 1980s the city had fallen on hard times again. Now, thanks to a campaign to preserve the pastel-hued buildings of Ocean Drive's Art Deco Historic District, the city gained new kitsch and hip credentials and is awash with upscale restaurants, design hotels and lavish residences.

Then: Great Barrier Reef, Queensland, Australia

Timothy Baxter/Shutterstock

The Great Barrier Reef off the northeast coast of Australia is the world’s most extensive coral reef ecosystem. It covers an area of 134,363 square miles (348,000sq km) and is home to over 1,500 species of fish, about 400 species of coral, 4,000 species of molluscs, and some 240 species of birds.

When it added the reef to its World Heritage List, UNESCO described the area as having “some of the most spectacular maritime scenery in the world”.

Now: Great Barrier Reef, Queensland, Australia

Darkydoors/Shutterstock

Sadly, global warming has seen this vibrant underwater wonder lose much of its vibrancy. Rising ocean temperatures in the Great Barrier Reef have caused vast swathes of coral to expel the microscopic algae that live in their tissues, exposing their white skeletons.

This is called bleaching and places the coral at risk of starvation and diseases. Coral can recover from bleaching if temperatures drop and conditions return to normal.

But with the reef experiencing its fifth bleaching event in eight years in 2024, a full recovery is looking more and more unlikely.

Then: Baltic Flour Mill, Gateshead, England, UK

Wikimedia Commons/Public Domain

This gigantic flour mill built by Rank Hovis in 1950 dominated the south bank of the River Tyne in Gateshead, northeast England, for decades and at its height employed around 300 people. By 1981, only 100 workers remained and as demand dropped, the company decided to close the mill. The vast Baltic Flour Mill sat vacant for the next 20 years.

Much like the transformation of London’s former Bankside Power Station into the Tate Modern, the Baltic Flour Mill has since been repurposed into a capacious contemporary art gallery.

Now: Baltic Flour Mill, Gateshead, England, UK

larry mcguirk/Shutterstock

The redevelopment began in 1998 and by 2002 Newcastle had a new modern art gallery, the Baltic Centre for Contemporary Art, otherwise known as BALTIC. It is famous for its international programme of contemporary visual art, exhibiting artists like Yoko Ono, and in 2011 it hosted the Turner Prize, the first time the event had been held outside of London or Liverpool Tate.

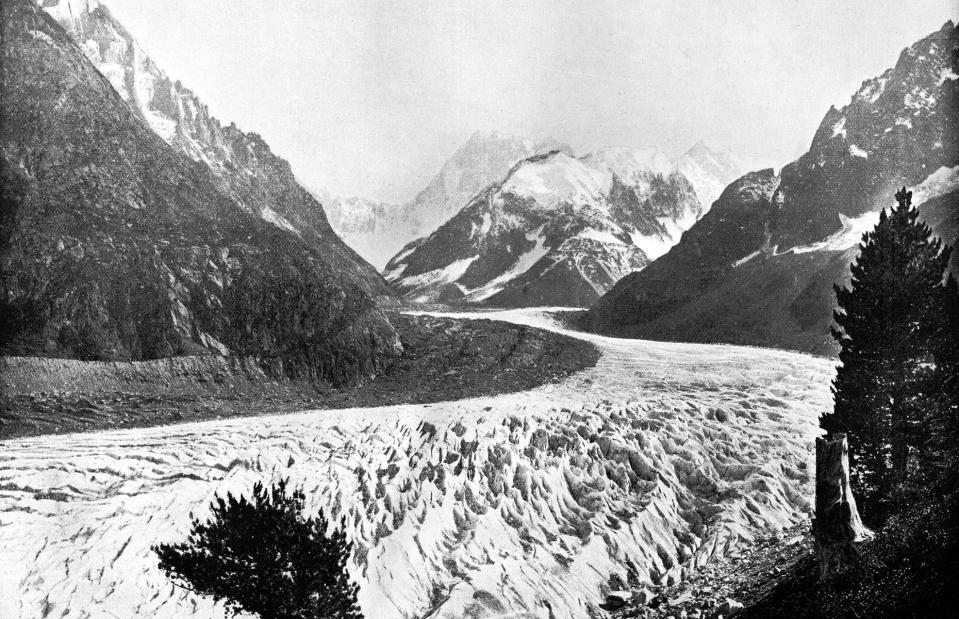

Then: Mer de Glace, France

Print Collector/Getty Images

When this photo was taken by John L Stoddard in 1893, the famous Mer de Glace glacier in France stretched the slopes of Mont Blanc all the way to the valley floor in Chamonix. People travelled from all over Europe to see this ‘Sea of Glass’ for themselves, with some ill-equipped folk stepping out onto the ice.

William Coxe, a travelling English historian, best captured the glacier’s awesome beauty in 1777 when he compared it to “waves instantaneously frozen in the midst of a violent storm”.

Now: Mer de Glace, France

OLIVIER CHASSIGNOLE/AFP via Getty Images

While Mer de Glace remains the largest glacier in France, it is retreating at an alarming pace. Scientists estimate that the glacier is melting at a rate of around 131 feet (40m) a year and has lost 262 feet (80m) in depth over the last 20 years alone.

Mer de Glace has withdrawn by 1.25 miles (2km) since 1850 and research indicates that it could retreat by another three quarters of a mile (1.2km) by 2040. This photo taken in 2023 shows tourists on a viewing platform where only 50 years earlier, the ice was almost close enough to touch.

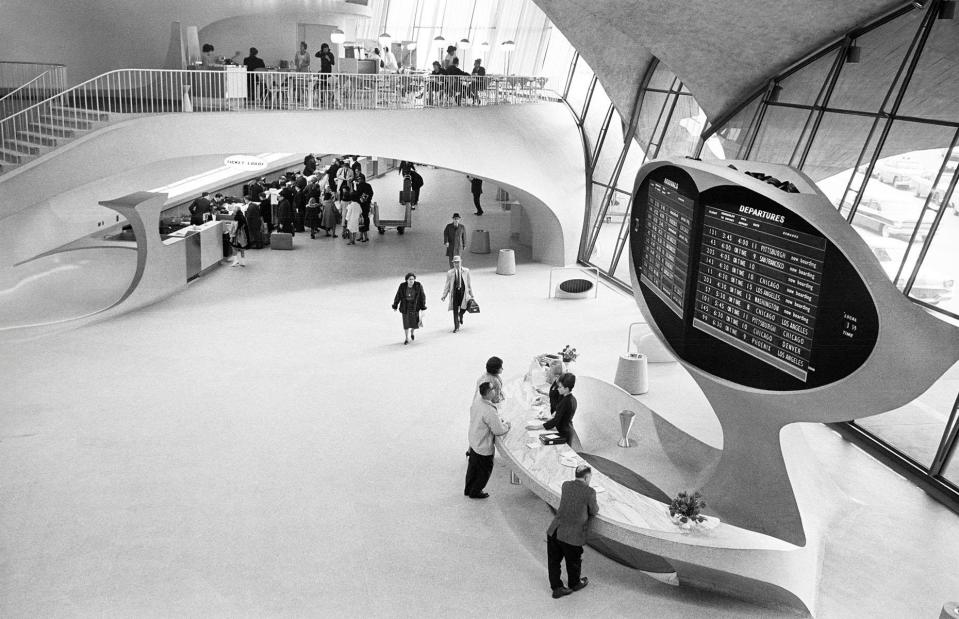

Then: TWA Flight Center, JFK Airport, New York, USA

Glasshouse Images/Alamy Stock Photo

When the TWA Flight Center at JFK Airport opened in 1962 its vast open spaces and smooth lines perfectly captured the romance and excitement of the glamorous new age of jet travel. The elevated walkways were designed to sweep passengers directly to their plane, while the airy waiting area was the perfect place to sip on a martini while keeping a close eye on the space age departure board.

As can be seen in this photo taken in 1965, Eero Saarinen’s masterpiece became what all other airports aspired to be.

Now: TWA Flight Center, JFK Airport, New York, USA

Randy Duchaine/Alamy Stock Photo

The TWA Flight Center operated as a terminal until 2001 when it was closed because it could no longer support the size of modern aircraft. Nearly two decades later it was repurposed in all its mid-century glory as a top-class hotel – the first onsite hotel at JFK.

It boasts 512 ultra-quiet guestrooms, sophisticated bars and restaurants, museum exhibits on the Jet Age and the mid-century modern design movement, plus a Twister Room, where you can play a wall-to-wall version of the 1960s game.

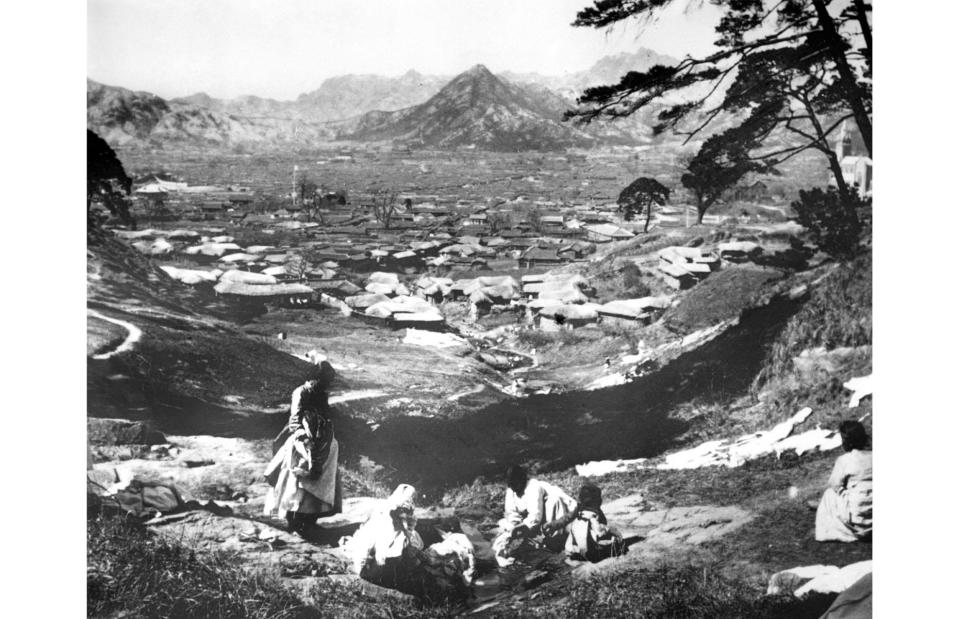

Then: Seoul, Korea

Art Media/Print Collector/Getty Images

For much of the 19th century, Korea shunned the outside world. King Kojong was too young to rule when he ascended the throne in 1864 so his father Yi Ha-ung became the de facto ruler. He pursued a policy of national exclusionism, often resorting to violent means, including the sinking of the American merchant ship General Sherman in 1866.

When Ha-ung relinquished power in 1873 and Korea opened up to the world, foreign merchants found a society that hadn’t changed for centuries. Much like this photo taken on a hillside overlooking Seoul in 1900.

Now: Seoul, Korea

Sean Pavone/Alamy Stock Photo

Once the doors were opened, Koreans embraced modernisation with gusto. Seoul became the first city in East Asia to have electricity, trolley cars, water, telephone and telegraph systems and was hailed as the 'cleanest city in the East'.

The country would face setbacks with the Japanese occupation between 1910 and 1945 and the Korean War between 1950 and 1953. But that drive for modernisation and innovation continues to this day, not just in industry but in culture too with Korean movies, music and food currently taking over the world.

Then: Berlin Central Station, Germany

Public Domain via Wikimedia

The history of Berlin’s Central station is as storied, volatile and dramatic as the city itself. It began back in 1871 with the opening of the gorgeous Lehrter Bahnhof, built in the French Neo-Renaissance style that was all the rage at the time.

It was known as a 'palace among stations' and in 1882, a smaller interchange station, Lehrter Stadtbahnhof, was built next to it to provide connections with new lines. Sadly Lehrter Bahnhof was heavily damaged during the Second World War and had to be demolished.

Lehrter Stadtbahnhof survived and continued working as a S-Bahn stop.

Now: Berlin Central Station, Germany

Ansgar Koreng/CC BY 3.0/Wikimedia

After German reunification it was decided a new central transport hub was needed for the city and in 1992, Lehrter Stadtbahnhof was demolished to make way for the glittering glass Berlin Hauptbahnhof. It was one of the most spectacular architectural projects in the newly reunified capital and the largest and most modern connecting station in Europe.

A sophisticated system of large openings in the ceilings allow for natural light to reach even the lowest tracks. Here we see it at dawn reflecting in the water of Humboldt harbour.

Then: Serengeti safari, Tanzania

Osa & Martin Johnson Safari Mus./Getty Images

The Serengeti National Park stretches over 5,700 square miles (14,763sq km) in northern Tanzania and is famous for the spectacular wildebeest migration each year. It is also home to the largest lion population in Africa. When American explorers and documentary filmmakers Osa Johnson and Martin Johnson visited in 1928, it was still in the process of becoming a game reserve and visitors were few and far between.

Here we see the couple in their specially modified 'camera car'.

Now: Serengeti safari, Tanzania

Ariadne Van Zandbergen/Alamy Stock Photo

After the Serengeti became a national park in 1951, its fame grew and soon people were travelling from all over the world to see the two million ungulates, 4,000 lions, 1,000 leopards, 550 cheetahs and some 500 bird species that populate this UNESCO World Heritage Site. Despite the park’s vast size, things are a little more crowded than when the Johnsons visited in 1928.

More than 350,000 people visit the Serengeti each year, often descending on the same spot when a wildlife superstar, like the leopard in this photo, is spotted.

Now discover the earliest ever photos of the world's national parks