The Explorers: shining a light on the diverse men and women forgotten by history

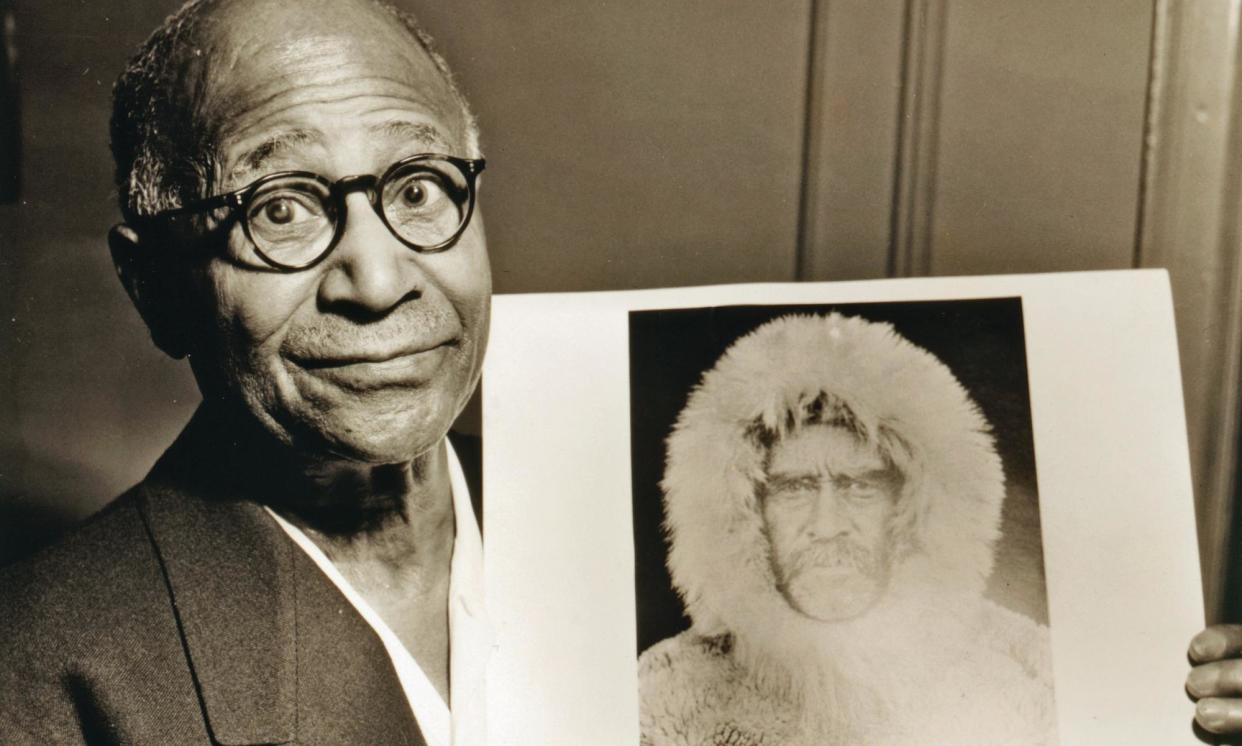

At the top of the world the colour line thawed and melted away. In 1909 Robert Peary, a white naval officer, and Matthew Henson, an African American son of sharecroppers, survived ice storms, back-breaking marches and sheer exhaustion to plant the Stars and Stripes at the north pole.

But once the pair set foot back on American soil, the gravity of Jim Crow segregation reasserted itself. Leary was hailed as a hero by the press. Henson went mostly unsung – and was soon cast aside by Peary himself.

Related: ‘We’re going to find the next Shakespeare’: inside DC’s $80m library renovation

His courage resurfaces in The Explorers: A History of America in Ten Expeditions, a book by the historian Amanda Bellows that focuses on 10 adventurers, from the Indigenous American navigator Sacagawea to the astronaut Sally Ride, whose discoveries shaped US history but who were often excluded from the canon.

America is a nation of explorers. “Go west, young man,” is a phrase often credited to the author and newspaper editor Horace Greeley. “That’s one small step for man, one giant leap for mankind,” said Neil Armstrong, the first human to set foot on the moon.

Bellows’s book celebrates this restless spirit while acknowledging its dark side of violent displacement and environmental destruction. She also challenges the image of the American explorer as a rugged white man, dominant in popular culture thanks to 18the-century figures such as Daniel Boone, Davy Crockett, Jim Bowie, Sam Houston, Jim Bridger and Kit Carson.

“The archetypical explorer that many Americans think of today is a figure like Daniel Boone,” Bellows says by phone from the New School in New York, where she is a historian of the United States. “He was a white male frontiersman who blazed a trail into Kentucky territory in the late 1700s.

“There was this cult of Daniel Boone that grew over the years. He was popular in Europe, where his autobiography was reprinted and circulated widely. Then in the 1960s there was a television show about Daniel Boone featuring Fess Parker and lots of memorabilia for the mass market. But the story is much broader than the story of these men.”

Bellows’s favourite subject was Henson, born to sharecroppers in rural Maryland a year after the abolition of slavery. In 1888 he was working in a hat shop in Washington when he first met Peary, who offered him a job as a valet on a trip to Nicaragua, the first of many they took together including several journeys to the Arctic.

From his earliest days as an adventurer, Bellows writes, Henson encountered white people who doubted his abilities to survive the Arctic climate because of his race. “He remembered one conversation during which he was told that he ‘couldn’t stand the cold – that no black man could’.

In 1908, Peary and Henson set off on their most ambitious quest yet: a year-long expedition to the still undiscovered north pole. For the final, treacherous phase they were accompanied by four Inuit men: Ootah, Ooqueah, Seegloo and Egingwah. At one point an exhausted Henson fell into the sea and was rescued by Ootah. Finally the group’s scientific instruments showed they had reached the north pole, where they triumphantly planted an American flag.

But back in the racially segregated US, Henson was given little recognition for his role in leading one of the two teams of Inuit men. A front-page headline in the New York Times declared: Peary Discovers the North Pole After Eight Trials in 23 Years. Nine days later, a Times story gave Henson’s perspective but described him as Peary’s “colored lieutenant”.

Other newspapers cast Henson’s role in paternalistic or racist terms, the book notes. The Tacoma Times called him Peary’s “black bodyguard”, a man whose “devotion to his master [was] unbounded”. One journalist wrote that Henson’s success refuted “the general supposition that the negro can’t stand cold weather and is a warm climate person only”.

Henson lived for almost half a century after his return from the North Pole but fell out with Peary, whom he last saw in 1910. Henson’s wife, Lucy, told the San Francisco Chronicle: “Since they returned from the North Pole, Peary has dropped Matt entirely, and has held no communication with him nor done a single thing in recognition of his 23 years of service … So far as Peary knows, or cares, for all the interest he has shown, Matt might be starving to death. Such ingratitude is pretty hard.”

Peary’s claim to be the first to the north pole was also dogged by controversy about the accuracy of his measurements and the rival claim of another explorer, Frederick Cook, to have reached the pole in 1908.

Henson published an autobiography, A Negro Explorer at the North Pole, in 1912 but struggled to find a new career. At one point he worked as a maintenance man in a garage in Brooklyn, New York, earning just $16 a week.

He gained some financial stability in the clark office of the US Custom House in New York. Only in later life did he receive recognition from Congress and the White House. More than 30 years after his death, Henson’s remains were reinterred at Arlington National Cemetery, near the graves of Josephine and Robert Peary.

Bellows reflects: “He was likely the first person to reach the north pole as part of Robert Peary’s expedition. But when they came back Peary, who was a white naval officer, got all the attention in the newspapers.

“In the Jim Crow era, newspapers significantly downplayed Matthew Henson’s critical role in the expedition – being a master dog sledder and fluent in Inuit language and so forth. The role of the four Inuit men who were on that expedition also got overlooked as well.”

Bellows, 38, took a two-week road trip in 2021 from St Louis, Missouri, to Astoria, Oregon, following the route of Meriwether Lewis and William Clark’s expedition with the Corps of Discovery at the start of the 19th century. Her book’s first chapter is about Sacagawea, a Shoshone woman who was navigator and interpreter for Lewis and Clark.

It tells how Sacagawea was kidnapped by an enemy tribe when she was 12 and brought from her homeland in present-day Idaho to present-day North Dakota. At 16, she was forced into marriage to Toussaint Charbonneau, a French Canadian trader aged about 37. She was pregnant with his child at the time the Corps of Discovery made its winter fort in North Dakota.

Charbonneau offered his services to the Corps of Discovery, adding that his two Shoshone wives could act as interpreters; the expedition’s co-commanders agreed to bring Charbonneau and one of his wives. The job went to Sacagawea, who had an eight-week-old son. “She must have had so much fortitude and courage to make that journey,” Bellows comments.

“There’s so much knowledge acquired for the country on that trip in terms of geography, in terms of animals and plants, knowledge about Indigenous peoples. Lewis and Clark took copious notes in their journals and those are an incredible primary source. But in the aftermath of that expedition we have so much settlement and that has a very negative impact on Native Americans.”

Chapter two is about James Beckwourth, a gold rush pioneer and discoverer of the Beckwourth Pass in California. He was born into slavery in Virginia at the turn of the 19th century. His family moved to St Louis, Missouri, the gateway to the western frontier, where his father, who was white, signed his emancipation.

Bellows goes on: “He’s hearing all these stories from these fur traders and trappers who are doing trading in St Louis and he says, ‘I’ve got to see the Rocky Mountains.’ That’s what hooks him on exploration. He was an entrepreneurial and creative figure. He’s all over the continent, always in the right spot at the right time, engaging in the most interesting activities.

“He’s in California when the gold rush begins. He makes his way north and he’s out prospecting for gold when he comes across the lowest pass through the Sierra Nevada. He basically turns it into a road.

“He works on construction and hires some other folks to do it because he thinks that, rather than finding a little bit of gold, it would be more profitable to turn this discovery into something that will fuel settlement. Then he settles in that region for a while and has his own inn and welcomes people into California.”

Other chapters focus on Laura Ingalls Wilder, a homesteader and author of Little House on the Prairie; John Muir, a Scottish-born naturalist and advocate for the preservation of wild areas; Florence Merriam Bailey, an ornithologist and nature writer; and Harriet Chalmers Adams, who explored the entirety of South America.

Then there is William Sheppard, born in 19th-century Virginia and raised in a Presbyterian household. He went on to become the first African American missionary to reach what was then the Belgian Congo under colonial rule.

Bellows elaborates: “He goes there with a partner named Samuel Lapsley, who was the white son of a former slave holder, so an unlikely pair during the Jim Crow era when lynching rates are at their peak and there’s so much discrimination in the United States.

“The two men become extremely close because they have this partnership. They become like brothers during their missionary work to the Congo. Lapsley dies pretty quickly of malaria and then Sheppard has to carry on the mission on his own.”

Sheppard uncovered evidence of the atrocities that Belgium’s King Leopold II was perpetrating against the Congolese people. “He goes out, he interacts with the people that are perpetuating this genocide, which is dangerous of course, and then he goes and he writes a critical report that got international attention when it was published.

“Then he also testifies against the Kasai Rubber Company, which sues him for libel. He put himself on the line and was not only a missionary, not only an explorer, but also an activist. An amazing figure.”

The book finishes with two women who explored air and space in the 20th century. In the tradition of Boone, all 12 people who have walked on the moon were white men. But Sally Ride became the first female, and the youngest American astronaut, to reach space when she flew onboard the shuttle Challenger in 1983. She was something of an enigma even to close friends.

Bellows comments: “She was a brilliant person. She was an incredibly hard worker. In the archives that I looked at online, you can see her notes from training and you can see that she was just a wonderful student and devoted to mastering the tasks that are required of an astronaut. Those are the reasons she was ultimately chosen to be the first American woman in space.”

Amelia Earhart, born in Atchison, Kansas, in 1897, was the first female aviator to make a solo crossing of the Atlantic Ocean. She disappeared in July 1937 on a flight over the Pacific Ocean while trying to become the first pilot to circle the globe at the equator.

Bellows says: “She may not have technically been the most skilled aviator of her day but she was certainly incredibly determined to try and set new records and fly new routes. She was always working hard. That passion and determination is evident when you look at her story.”

Did Bellows spot any common threads linking the explorers? Her study of Earhart offered a clue to at least one potential trend. “You have to have a high tolerance for risk to do the kinds of things that these people are doing and she didn’t have a lot of secure attachments,” the author says.

“She had a tough childhood. Her father was an alcoholic; her parents weren’t living at home; she was raised by her grandparents for a lot of the time. She didn’t really want to get married to George Putnam, her publicist, but she agreed. She didn’t have children.”

Bellow adds: “Sometimes, in some of these explorers’ biographies. you see a lack of strong attachments with other people. I wondered as I was researching this: to what extent does that lack of attachments make someone more tolerant for high levels of danger and risk to your life?”

The Explorers is out now