The evolution of the travel scam – from fake antiques to internet fraud

When Shelley and Byron headed off on their round-Europe adventures, a little light con artistry was par for the course. The Grand Tour – a visit to key artistic sites in Italy, traditionally conducted by upper-class young men in the 18th and 19th centuries – was seen as a way for the nobility to mature and learn life skills. And, if they ran into trouble along the way, so much the better.

Writing in Masculinity and Danger on the Eighteenth-Century Grand Tour, Sarah Goldsmith notes: “In the era of fashionable games of chance, elite families understood the Grand Tour as an enormous, costly jeux de societé; a gamble with the family’s finances, with their sons’ lives and reputations, and with a whole variety of hazards.”

A fabled version of Italy fuelled the fire. Visitors were taught to expect fights and robberies – though, in reality, they may have been more likely to fall foul of their guide’s plot to flog a dodgy ancient amphora. The country may have been known as a place to find cheap antiques, but there was a reason why prices were so low.

Tourism has become more mainstream with the passing centuries, but some cons are as old as time – and new research suggests that Italy may still be the place where European tourists are most likely to be targeted for petty crime. Travel insurance website Quotezone.co.uk’s 2024 European Pickpocketing Index, which sets the number of incidents reported at a country’s top five attractions against visitor numbers, placed Italy top of the table, with France and Spain in second and third place. Founder and CEO Greg Wilson warned people to be vigilant around ““iconic attractions like the Eiffel Tower in Paris and the Trevi Fountain in Rome”.

Among the traditional scams to be aware of are Paris’s gold ring hoax – where a stranger pretends to pick up a ring you’ve mistakenly dropped as a distraction technique. In Granada, tourists writing on review sites report falling foul of a “pigeon poo” scam, during which a man sprays fake bird faeces on an unsuspecting tourist then pretends to clean it up, stealing valuables in the process.

Other cons take an old-fashioned bent too. In Venice, unscrupulous gondoliers have been upping the price of a ride on their boats forever – once they have you out on the water, that is (the price should be €90 for 30 minutes during the day and €100 after sunset).

But the scammers of old didn’t just think small – some had more ambitious ideas. Notorious con artist Victor Lustig (best known for falsely selling the Eiffel Tower) allegedly honed his trade on ocean liners cruising between France and New York City, where he persuaded rich passengers to invest in a non-existent Broadway musical. Meanwhile, American scammer George C Parker was known for flogging New York landmarks to fresh-off-the-boat immigrants and clueless tourists: among his fraudulent sales were the Statue of Liberty and the Metropolitan Museum of Art, as well the Brooklyn Bridge.

The timeshare years

Fast-forward to the 1960s and a new real-estate-related con scheme began to take hold: the timeshare. One of the industries to profit from cheap flights to the Continent, these developments spread through Spain and the Canaries in a flurry of aggressive sales tactics and dodgy contracts. Among them was one run by John Palmer, notoriously linked to the Brink’s-Mat robbery which was serialised in recent BBC TV series The Gold.

By the end of the 20th century, the timeshare industry’s image problem necessitated a makeover and terms such as “holiday clubs”, “vacation ownership” and “fractional ownership” appeared on the scene. The idea behind these schemes was essentially the same, though customers often bought “points” to spend at resorts across the world rather than set weeks at one property.

“Essentially, you get your points, you pay your maintenance fee and you get to go on holiday – if you can ever find the availability,” says Keith Dewhurst of the Timeshare Consumer Association (TCA). “The product itself is pretty transparent. Where it goes wrong is the sales methods employed by the timeshare industry. People are lied to about what they’re buying. They will be told that, if they buy a week in Benalmadena in Spain, next year they can go to Bali. It doesn’t work that way. If you buy in Bali, you can spend your life in Benalmadena if you want to – but if you buy in Benalmadena, you’re not going to Bali.”

Another con exploded in the late 20th century. Travellers parted with thousands of pounds without even knowing it as credit and debit card cloning became mainstream. The ruse was simple: staff in restaurants might take a card away on the premise that the machine wasn’t working and then make a copy, or thieves would use skimmers at ATMs. This type of card fraud hasn’t gone away – but chip-and-pin technology means it is decreasing.

Web of lies

These days, travel scams are big business. From inflated taxi fares to adding extras to a restaurant bill, some are almost par for the course. But something else has increased the ease with which scammers can get their hands on our cash – the internet.

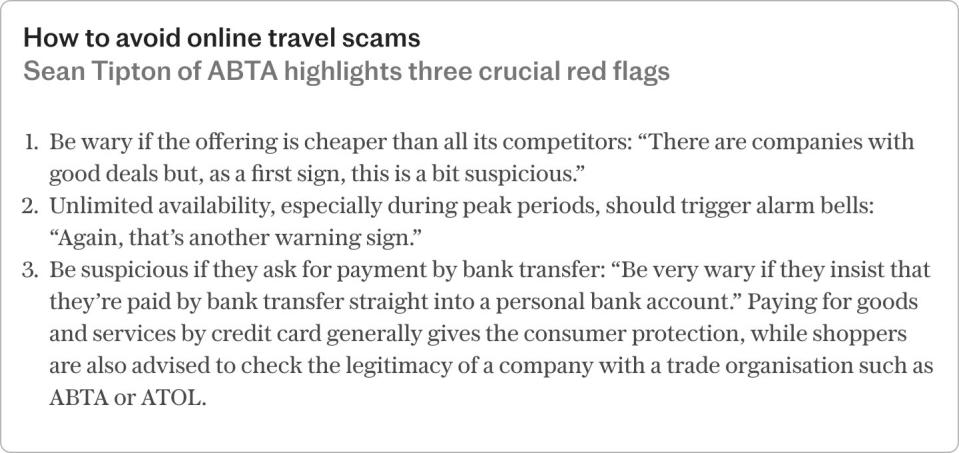

Sean Tipton of ABTA has seen an uptick in calls from people who have been scammed on social media, where fraudsters advertise villas and holiday apartments that don’t exist (or belong to somebody else), while the the trade association UK Finance reported that purchase scams were on the rise in 2023.

“Holidays, like everything else, have increased in cost post-pandemic,” said Tipton. “So people are much more inclined to look for really good deals. If you look at the time of year that fraudsters target, they go for Christmas and New Year and summer – they know that that’s when there’s a big increase in people looking for holidays, and they know that these will be more expensive.”

He noted that the fraudsters don’t price too low, undercutting just enough to offer a bargain without sounding alarms. And, in certain cases, victims don’t discover they’ve been conned until they reach their holiday accommodation and find that it doesn’t exist.

Another growing industry is fake websites selling flights, often to people heading off to visit family and friends. “The websites used to seem amateurish but they’re much more commercial now,” says Tipton. “They’re really convincing. We used to say that not having terms and conditions was one of the warning signs, but now they just copy someone else’s and stick them on their site. I’ve seen sites with pictures of the sales team and they were just random people plucked off the internet.”

The psychology of the holiday scam

Vicky Reynal, psychologist and author of Money on Your Mind, reveals why we fall for holiday scams and how they affect us. “The rose-tinted glasses we bring to a holiday mean we might be less likely to spot signs of deceit,” she says. “But unfamiliarity can make us feel tense and on edge too. That can make us vulnerable because, if a scammer approaches us sounding friendly, kind and helpful, we might feel relief that somebody has put us at ease and be more inclined to follow their suggestions.

“Feeling scammed evokes a mix of emotions including anger, sadness and shame. Anger could be harder to manage without a physical person in front of us to express it towards – when they are an ‘entity’ behind the screen, we cannot express our rage to them. We feel guilt when we make a mistake – but shame is about how we feel about ourselves, a sense of being ‘bad’ or in this case stupid, naïve or gullible. Shame is deep and it takes a long time to resolve.”