Evie Wyld: ‘It’s not the men who are toxic, but masculinity itself’

What’s it like having a novel published in the middle of a global pandemic?

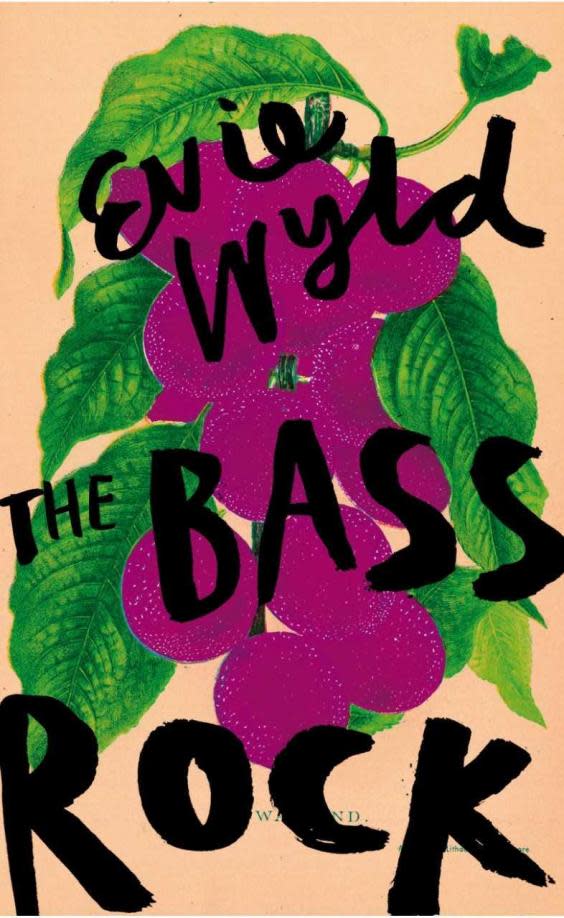

“Oh, the book feels completely inconsequential,” says Evie Wyld whose much-anticipated third book, The Bass Rock, is out next week. “I’ve just done my first bit of stockpiling; it’s mainly Twiglets and whisky.”

We meet in a café around the corner from the author’s home and the independent bookshop she co-owns in “Peckham Village”, southeast London, to talk about her dark, beautiful and funny gothic family saga for the #MeToo generation.

“Having been in the world of that book for five years and completely in a daze with it, I’ve snapped right out of it,” she says.

We very nearly cancelled the meeting due to the ongoing crisis, but decided to go ahead and sit with the dictaphone a healthy distance between us. I realise this might be one of the last in-person interviews for a while before we all self-isolate.

The 39-year-old author, who is wearing a black sweatshirt with a tiny “No” motif and and has red-raw knuckles from all the hand washing, rose to fame after her debut novel After The Fire, A Still Small Voice won the John Llewellyn Rhys Prize in 2009 when she was 29.

But considering coronavirus now threatens to overshadow her next big moment, as well as life as we know it for some time, she seems remarkably upbeat.

“It will be interesting to see what happens when no one goes out and what people want to read,” says Wyld. “There aren’t a great deal of books that are just for s**ts and giggles really. Novels tend to be about very difficult, sad or dangerous things.”

And so it is with The Bass Rock, an atmospheric book that transports you within a few sentences to the windswept coastal town of North Berwick, Scotland. Set against a gothic backdrop of the “incessant cries” of seagulls, the sea and foaming waves, windy weather, and a dead shark, Wyld tackles toxic masculinity in the parallel stories of three women, living at different times but linked by sisterhood.

There’s Ruth, living in the aftermath of the Second World War in an oversized house, whose new husband is gaslighting her and making her feel deranged; Viv, who, six decades later, catalogues Ruth’s belongings in the same house and who learns to trust her instincts after meeting her love interest in a romcom-style scenario; and Sarah, way back in the 1700s, who is accused of being a witch by the men around her and brutally turned against.

The tension is always building as the story takes on an otherworldly dimension, inspired by Wyld’s love of horror and supernatural books that she was obsessed with as a young girl, including the Point Horror series and Stephen King. There is an unsettling undercurrent running throughout the book, whether it is the macabre image of two fingers peeking out of a “bulging” black suitcase on a beach, the misshapen Bass Rock, “like the head of a dreadfully handicapped child,” or Ruth clutching a butter knife as she hears a noise upstairs, along with a great sense of humour.

“What links the three women is that, like the #MeToo movement, it is about women talking,” says Wyld, who started writing the novel one hour at a time when her newborn baby was napping at home.

“#MeToo happened when I was in the middle of writing the book. I already had a draft of about 70,000 words. At the time I felt quite mad and sleep-deprived. I didn’t have time to think too hard about what would come out.” And yet the movement gave Wyld’s book some coherence. “It certainly joined everything together. When women talk about their experience, there is great power in that. And that, for me, was so invigorating about #MeToo.”

In particular, the book's “quite high body count” – eight murders throughout, as well as other deaths – highlights male violence against women. Wyld was inspired by the Australian Femicide and Child Death Map by the journalist Sherele Moody, which shows the heartbreaking reality of women and children murdered by men in Australia. But The Bass Rock also tackles more insidious behaviour. “Undoubtedly I will get a lot of ‘you don’t hate all men do you?’ questions with this book,” chuckles Wyld. “But the point is with toxic masculinity, it’s not the men who are toxic but masculinity itself, a thing which is imposed on men. It’s horrendous for women and horrendous for men.”

Wyld – whose husband Jamie publishes dog and cat haikus (“poems by dogs and cats,” she clarifies) and whose son, Buddy, is now 5 – lives in the lower level of her mother’s house, along with their Lurcher dog Scout. “We moved here when I was nine years old,” says Wyld, and eventually she bought her “mum’s basement”. She points to it over the road. “Our front room and the kitchen is my childhood bedroom – it’s very weird,” she says.

She feels a lot of pressure to “produce a good man” in bringing up her young son, “so that he is kind and in touch with his feelings”, she explains. “I think the thing that comes along with toxic masculinity is a huge suicide rate and the feeling they are not allowed to cry or voice feelings, and that they have the answer to everything.” In her book, she has deliberately kept sexuality and “perhaps even gender”, she says, quite fluid, as it’s implied that both Ruth and Viv may have had lesbian relationships.

“I am impressed by the younger generation,” says Wyld, laughing at positioning herself in the older category now. “They are able to inhabit their lives as they understand that whatever they feel is correct. For my generation, there was a lot of ‘Am I gay? Or not?’ which feels confusing.”

The Bass Rock is her first novel set entirely in Britain. Born in London in 1978, Wyld is the daughter of an Australian mother and British father and, while based in the UK, spent large chunks of time Down Under, at her grandparents’ sugar cane farm in northern New South Wales while she was growing up. Her first book After The Fire, A Still Small Voice was about three generations of Australian men and the trickle-down effect of the Vietnam war in Korea on their relationships with each other and the women in their lives. Her next, 2013’s All The Birds Singing, explored female trauma and the ingrained guilt that women carry, focusing on an Australian sheep farmer working on an English hill farm, and switching between the two countries.

The switch to Scotland for her third book, though, is coupled with more autobiographical details. She admits that the character Viv is a “thinly veiled” version of herself, both of them mourning the death of their fathers. The internal dialogue about what to buy in a supermarket – purchasing plums and some bread to look sensible – has an element of romcom about it, but Viv breaks out of the mould. Ruth, meanwhile, is based on Wyld’s English grandmother – “a very particular person – like cut glass, a very tall scary alcoholic chain-smoker”.

“I inherited her photo albums,” Wyld continues, “and I saw all these beautiful pictures of the Bass Rock, because it’s a place my family had gone for a long time. I saw my family having wintry picnics with the gannets… and there was my grandmother… this sexy vital human being.”

Likewise, Wyld stands out. Australian author Tim Winton’s Cloudstreet was the first novel she read that made her want to write. Other influences include The Magic Toyshop by Angela Carter. “The pleasure reading I was doing as a child was not high brow,” says Wyld. “My mum took me to a bookshop and said my daughter has a really weird, morbid reading obsession,’ and they recommended American novelist Virginia Andrews, which is just like one long rape fantasy. And then I was obsessed.”

It’s a rare moment of dark humour during our interview. Wyld, who in the past has been bombarded by people suggesting her career was over when she got pregnant, now feels that she can’t behave like male writers.

“I think there is pressure as a female writer to be overly serious and overly nice at the same time," she says. "I think I am a nice person anyway, but I am very aware that if I behave like a male writer, I would be a difficult person to work with. Whereas a male writer can be demanding and grumpy. The first literary event I ever did for my first novel, which was written in a male voice, the male chair asked what made me write about men’s stories rather than just write chick lit? That was literally the first question I ever got asked. I’ve been asked before how I find time for my husband – ‘How do you manage to keep him happy with all this going on?’ With all of this stuff you have to contend with as a woman, I think it’s very difficult to get to a level where you are producing enough work to be taken seriously… as a woman who is engaging with family life as well.”

Despite the coronavirus pandemic, Wyld is excited about her new novel. She says she feels closer to nailing the themes that she keeps returning to, book after book. “All my novels are all about the same thing really – which is toxic masculinity and being unable to communicate,” says Wyld, “but after the first two books, each time I finished them it wasn’t quite there. This time it is closer.”

The Bass Rock is published by Jonathan Cape / Penguin Random House is published on 26 March, £14.99

Read more

Why Hachette were wrong to cancel Woody Allen

Why we need angry girls in children’s books more than ever

David Lammy: ‘The extremes in the Labour Party have been horrendous’