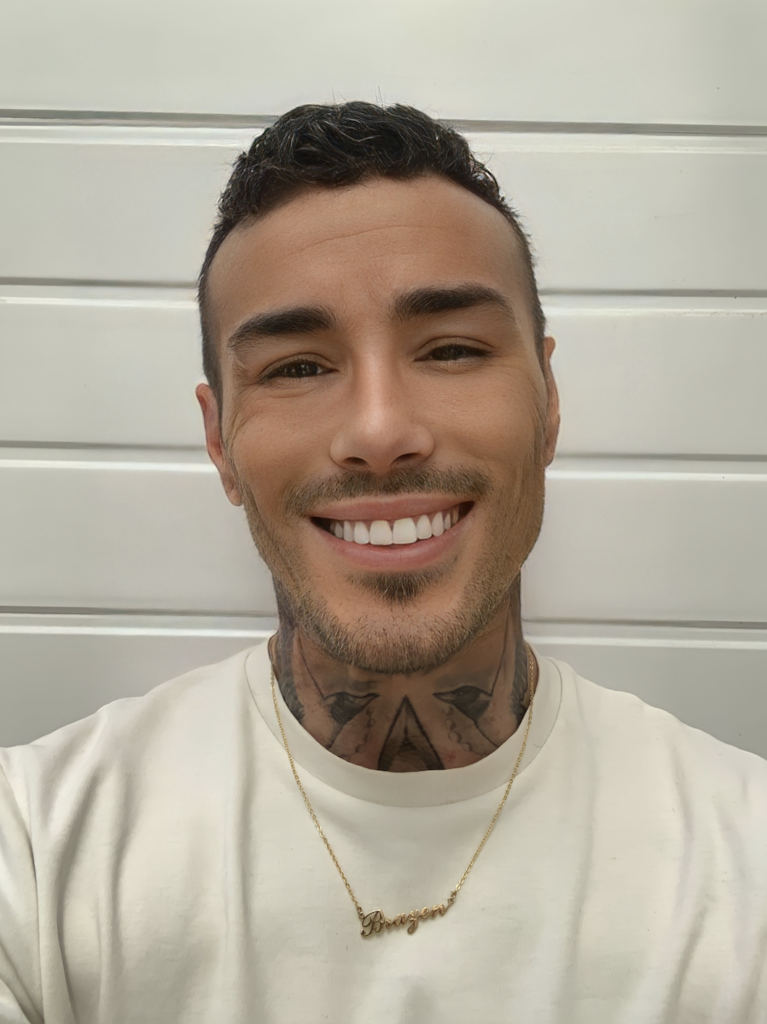

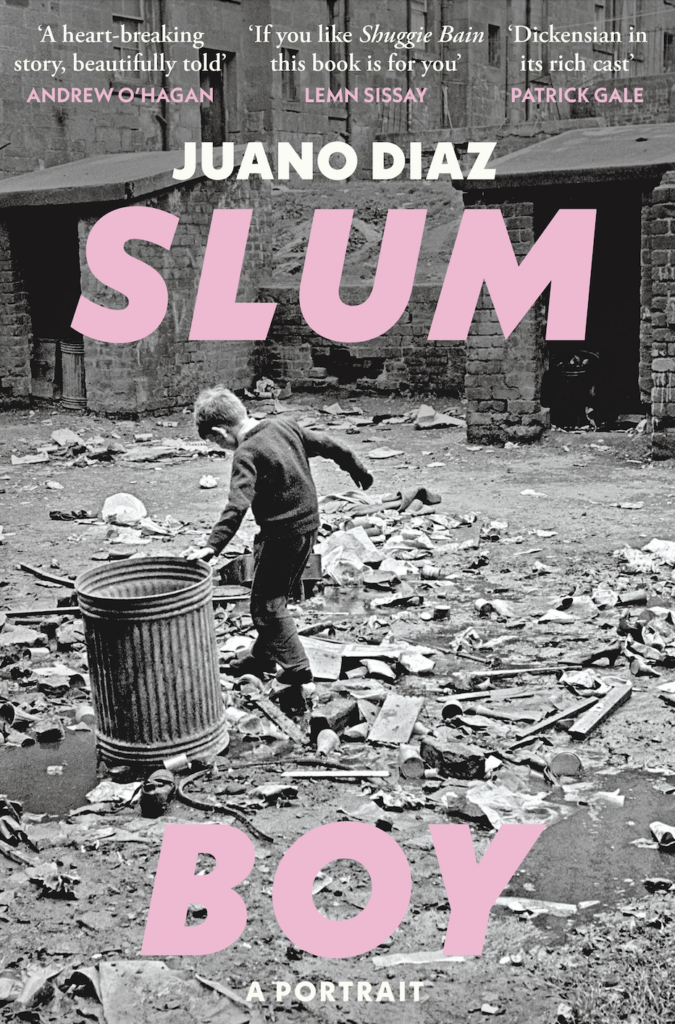

‘Everyone in my village knows I’m gay except my parents’: Slum Boy’s Juano Diaz on the teen love affair that inspired this artwork

Mum is wrong about me not having any friends; I do have a couple at school. I met an older boy who works in the chip shop in Coatbridge, too. At school lunchtime, he serves me. Sometimes he takes a break and stands outside and smokes, chatting with the popular boys who are fussed over and adored by the popular girls. When he does this, I purposely keep my distance, and head elsewhere for lunch.

Then he joined Dad’s boxing club and somehow over the training we bonded. He is a boy called Mario. We never speak at lunchtime in the chip shop; in fact, he goes out of his way to ignore me when he sees me standing in the queue to be served and sometimes he laughs when the bullies call me names. He doesn’t want anyone to know that he knows me.

After boxing, I sometimes walk him home along the old railway. Over the back fields, we have a secret den in an abandoned signal station that leads to the crumbling local steelworks, far from people, deep in the trees and overgrown nettles and weeds. Here we hide out, smoke cigarettes. Mario’s uncle died from AIDS in 1987 and his family are now very prejudiced towards homosexuals. They don’t like me any more either.

You’re William MacDonald’s laddie! his dad had said with a crushing manly handshake the first time we met.

Having a well-respected dad, a Gypsy man, a boxer and the local scrappy, covered me as a true man’s man for a few weeks, but Mario’s father eventually noticed my ways, the crop tops, mascara on my eyes and the way his son would watch me through downcast lashes in the family’s kitchen.

My dad says I’m not allowed you back over, Mario told me.

It seems everyone in my village knows I’m gay except my parents. The village turn their heads and laugh, but nobody ever says anything to me, they won’t dare, not with William MacDonald as a father.

Things have not been the same since I stole that money and declared my plan to escape, but with time, my punishment is lifted, and I am trusted again to go outside with Mario.

So why did you do it? he asks, passing me a cigarette his lips have wet. I dunno. I shrug. I want to get away from here.

Aren’t you embarrassed?

Suppose so. I turn away. As we trudge through the fields, the chill of the evening air seeps into my bones.

Where would you go if you had the chance to escape? I ask him, crunching over the nettles beneath our feet.

John, I’m OK here. I just want to be happy.

We arrive at our den. Inside the signal station are the remnants of our last time here: charred remains of our campfire and cigarette ends. This building is special; it is curved like a mini lighthouse but only has three storeys. It even has a spiral staircase right in the middle. The second floor is dark and dingy, with old cupboards covered in moss, but the third floor has windows 360 degrees round. I guess they allowed the signal master to see the trains coming and going long ago when this place was in use. There are levers, switches and dials, all rusted tight. The glass is missing from most of the windows; we lobbed bricks through them for fun months ago, so everything mechanical is now rotten from exposure.

The old railway lines that once took steel to and from the steelworks are still here, but nature has reclaimed them. Behind us are the famous steelworks that were closed back in 1986 while Thatcher was in power. Amid this decaying metropolis of industry, there is a glimmer of renewal. Slowly but surely, the forces of nature are taking hold; silver birch has taken root in the cracks of concrete and lush greenery spills over the edges of rusting machinery. The once mighty furnaces and smokestacks stand as a testament to a bygone era, yet at the same time they serve as a reminder of the resilience of the natural world.

Mario and I have covered every inch of this decaying interior. We have carefully edged along steel beams one hundred feet up, and climbed into unused pits and steel drums. It’s the biggest building I have ever seen. From its roof, you can see far over the fields, all the way to Glasgow where my life started. The freezing wet air is punctuated by the sound of distant cattle mooing; we kiss deeply to their chorus.

We stay up here, only letting each other go to light a smoke, and as time passes the fog around us gets so dense that we can barely see each other’s faces. Mario guides me by the hand, down the steps and out into the night. Hidden under the blanket of felty fog, we walk along the abandoned railway, hands interlocked, shivering and free.

Back in the den, we hog the fire we’ve made for warmth. Mario wraps his arms around me, settling my shivering body into his as we talk about life in a way I can’t at home or with anyone else.

He is always curious about my past and presses me for memories. He knows how difficult it is growing up in a tight-knit family full of macho barriers and strong family pride. He speaks about his uncle, and his fear of AIDS, and he sometimes cries. We haven’t been educated about what AIDS is; we are told that poofs die of AIDS. We are doomed to die.

Extracted from Slum Boy by Juano Diaz, published by Brazen, £20. For more information, visit OctopusBooks.co.uk.

About the author: Juano lives in Wiltshire with his partner David and their son. He is an internationally acclaimed artist and collaborates with many others including Pierre et Giles and Grace Jones. His work has been exhibited in galleries across the world including at the Museum of Modern Art in New York.

@juanodiazartist

The post ‘Everyone in my village knows I’m gay except my parents’: Slum Boy’s Juano Diaz on the teen love affair that inspired this artwork appeared first on Attitude.