The eeriest deserted towns in the world

Lost towns around the globe

bmphotographer/Shutterstock

From Gold Rush-era mining towns cast out in the desert to ancient cities ravaged by time, the world is filled with abandoned settlements that act as a window into the past.

Read on as we take a virtual tour of the dusty streets and creaking buildings of the planet's eeriest deserted towns.

Houtouwan, China

Johannes Eisele/AFP/Getty Images

There’s something humbling about the way Mother Nature has claimed this fishing village for her own. The deserted homes in Houtouwan, on China’s Shengshan Island, are choked by vines, which climb up the brick walls, blanket the roofs, and creep through the glassless windows. Some 2,000 people once lived here, but today the village is almost entirely abandoned.

Houtouwan, China

Johannes Eisele/AFP/Getty Images

Houtouwan’s fishing industry once thrived, but the island’s remote location, coupled with competition from other, larger settlements, sent business into a downward spiral. Conditions were tough and, by the 1990s, there was almost no one left. Today, wild greenery and decades-deserted houses are the island’s main residents.

Bodie, California, USA

Mariusz S. Jurgielewicz/Shutterstock

There’s a reason this is the USA’s most famous ghost town. It’s as if time simply stopped in its tracks in Bodie – a deserted settlement in the Sierra Nevada – with its rusted out cars and rickety-looking houses acting as echoes of centuries past. Prospectors struck gold in the mid-1800s and Bodie soon blossomed into a mining boomtown, with saloons, homes, and some 10,000 residents. Its heyday was short-lived, though.

Bodie, California, USA

Boris Edelmann/Shutterstock

The downturn began at the end of the 1800s, when a fire ravaged parts of the town – but Bodie was built back up and wouldn’t be wholly abandoned until the 20th century. By the 1960s, it was declared a State Historic Park and it’s been protected in a state of “arrested decay” ever since. Inside the sunbaked homes, peeling wallpaper, creaking furniture and personal relics offer a glimpse into the lives of Bodie’s former residents.

Tyneham, Dorset, England, UK

Casper Farrell/Shutterstock

From a distance, this may look like any typical West Country village, with its limestone church, its pitched-roof buildings and its old-school phone box all folded into rolling countryside. But Tyneham has a rather sad story to tell. This is Dorset’s “lost village”, a long-abandoned, pre-war hamlet that was claimed by the military in 1943.

Tyneham, Dorset, England, UK

DavidYoung/Shutterstock

The villagers of Tyneham were forced to evacuate their homes in December of 1943, as their hamlet was chosen as army training land. Residents thought they’d be able to return post-war, but they were ultimately not allowed to. Today the buildings, including the striking church and the schoolhouse, are filled with displays revealing photographs and stories from times gone by.

Bankhead, Alberta, Canada

Nick Fox/Shutterstock

The remains of Bankhead – a former coal-mining settlement in southern Alberta – are swallowed by Banff National Park. And the wild, leafy surrounds make the ruins all the more eerie. Bankhead was first established in the 1900s, when a mining operation began in this coal-rich site. However, the fossil fuel they discovered – intended to power steam trains on a railroad – wasn’t up to the job.

Bankhead, Alberta, Canada

cvm/Shutterstock

The coal here was brittle and hard to mine, and workers’ industrial strikes left an already declining operation even further in the dust. The mine closed in the 1920s and is now protected as part of Canada’s national park system. Remnants scattered in the Alberta wilderness include a hulking mine train, a carpentry shop, and a melting house.

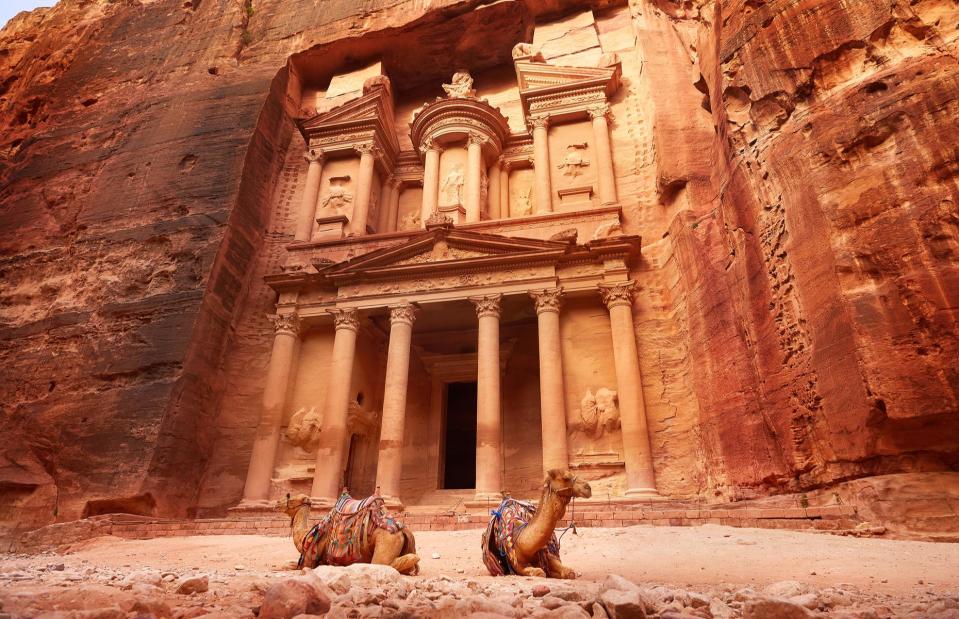

Petra, Jordan

Aleksandra H. Kossowska/Shutterstock

This ancient city hewn from sandstone is deservedly one of the New7Wonders of the World – and its sunset-coloured buildings have many a tale to tell. Petra was inhabited by the Nabataeans as early as 312 BC, operating as an important trading post for several centuries. When the settlement was swallowed by the Roman Empire its importance began to dwindle, and a series of earthquakes sealed its ultimate fate.

Petra, Jordan

tenkl/Shutterstock

It’s thought that the city of Petra was mostly abandoned by the 8th century and today, its remnants have a haunting quality about them. The most famous of the ancient structures is Al Khazneh or “the Treasury” (pictured previously), a jaw-dropping building with columns and plinths, which was probably once a temple. Other evocative ruins include Ad Deir (pictured) – the monastery.

St Elmo, Colorado, USA

Alexey Kamenskiy/Shutterstock

Especially after nightfall, St Elmo’s string of wood-clad buildings wouldn’t look out of place in a horror film. The mining town sprang up in the 1880s with nearly 2,000 residents living off the bounty of gold and silver in the region. However, in the 1920s, the halting of a key railroad service meant that St Elmo’s inhabitants up and left, riding the last train out of town and never looking back.

St Elmo, Colorado, USA

Janis Maleckis/Shutterstock

What’s here today is actually a recreation of the original town, whose structures were mostly destroyed by a fire in the early 2000s. However, the huddle of ramshackle, wood-framed buildings – which include the town hall and a general store – look every inch the Gold Rush-era bolthole, and are just as eerie as if they’d stood here for centuries.

Belchite, Zaragoza, Spain

TravelKiwis/Shutterstock

Belchite’s bullet-ravaged ruins are an enduring reminder of the horrors of war. The town was all but destroyed in 1937, in a deadly battle during the Spanish Civil War which also claimed some 3,000 lives. Belchite stood devastated and, over the years, Mother Nature has finished the job, further eroding crumbling buildings and forcing greenery into the cracks.

Belchite, Zaragoza, Spain

David Herraez Calzada/Shutterstock

It was decided that Belchite would not be razed to the ground – instead, the ruins of the old town would be left to molder and remind prosperity of the brutal conflict. Therefore, little has changed since the 1930s: rubble still litters the streets, bullet-ridden buildings still stand and the haunting site has also been used as a location for several movies.

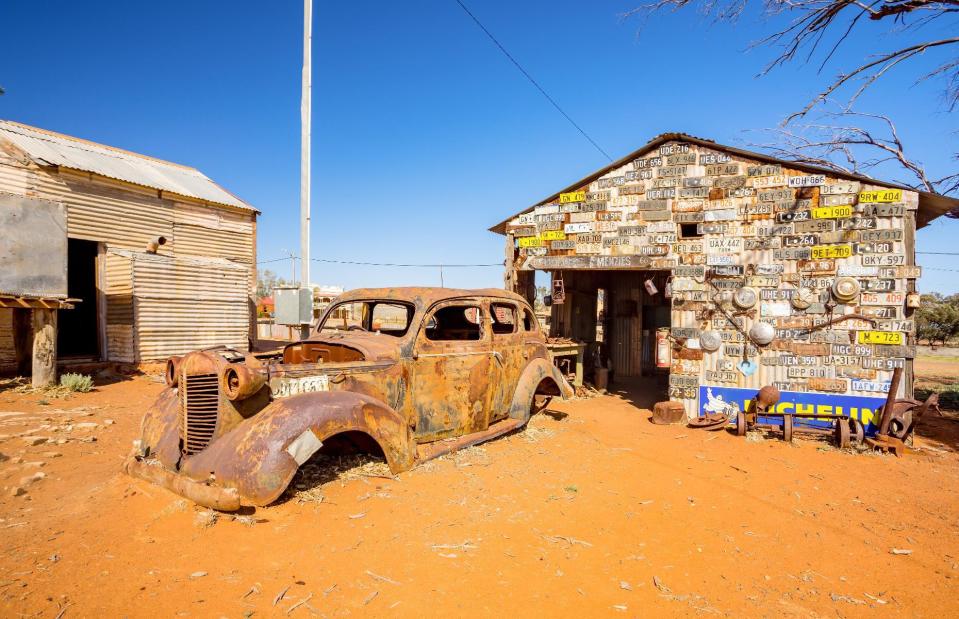

Farina, South Australia, Australia

Edward Haylan/Shutterstock

This outback ghost town had its heyday in the late 19th century, when it was settled by wheat farmers and was a stop along the iconic Ghan Railway. At its peak it had butchers’ shops, blacksmiths, churches and hotels, and the farmers benefited from unusually wet conditions. But, Farina’s luck soon changed. The region’s typically parched conditions took hold once more and the railroad was rerouted, leaving Farina in the desert dust.

Farina, South Australia, Australia

travellight/Shutterstock

By the mid-20th century, Farina’s population was in rapid decline and its buildings closed one by one. The town was eventually deserted entirely and its structures were left to crumble away. Ruins of the Transcontinental Hotel, the bakery, and other businesses remain a window into a bygone era, and efforts have been made to preserve them over the years.

Vijayanagar (Hampi), Karnataka, India

Nataliia Sokolovska/Shutterstock

Even in its ruined state, the medieval city of Vijayanagar (protected by UNESCO as the "Group of Monuments at Hampi") is a head turner. This abandoned settlement was once the capital of the Vijayanagar empire (whose name means “City of Victory”), and was first established in the 14th century. But the empire fell in the 16th century and its namesake city was destroyed and abandoned.

Vijayanagar (Hampi), Karnataka, India

Almazoff/Shutterstock

The city’s centuries-old ruins remain impressively intact today, a haunting reminder of a suddenly lost empire. Its ornamental temple complexes feature pillared halls, bold decorative archways, friezes and soaring stepped towers, and the most striking among them is Krishna and Vittala.

Wollseifen, North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany

Bennekom/Shutterstock

This desolate village is located in Germany’s Eifel National Park. After the Second World War, the hamlet was swallowed by the NATO Vogelsang Military Training Area (run by Britain and Belgium respectively), which also commandeered the site of a former Nazi “training center”. The inhabitants of the humble village, high on the Dreiborn Plateau, were evacuated, never to return.

Wollseifen, North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany

Gottfried Carls/Shutterstock

The training ground was operated by the Belgian military right up until the early 21st century, when it was finally vacated and folded into Eifel National Park. Now its decrepit buildings, including a creepy abandoned church, sit along a trail that routes through the wilderness.

Oradour-sur-Glane, France

Hansengbers/Shutterstock

This ghost town in central-western France has a somber tale to tell. In 1944, Nazi troops stormed Oradour-sur-Glane, brutally murdering 642 people and all but razing the settlement to the ground. The village is still much as it was after the massacre, serving as a tribute to those who lost their lives and a reminder of the horrors of the Second World War.

Oradour-sur-Glane, France

Ivoha/Shutterstock

The village appears almost trapped in time, with gutted buildings, burnt-out cars and everyday relics like sewing machines and kitchen utensils building a picture of that deadly day. There’s a striking memorial and a museum too.

Old Cahawba, Alabama, USA

Low Flite/Shutterstock

It’s hard to believe that this huddle of buildings – with their cloak of Spanish moss and their moldering façades – once made up Alabama’s state capital. Cahawba was state capital in the 1820s, and was dotted with elegant mansions, churches, and, of course, a grand capitol building. But the city’s position between two rivers (the Cahaba and the Alabama) meant it was prone to flooding and the decision was made to whisk the capital elsewhere.

Old Cahawba, Alabama, USA

Low Flite/Shutterstock

Tuscaloosa became Alabama’s new capital and Cahawba’s population took a nose-dive. Homes were abandoned and the town’s status was left in tatters alongside its buildings. Against the odds, though, Cahawba was built up once more in the decades after – but it had its fate sealed again during the Civil War when Confederate soldiers ripped up portions of the railroad here. Once more, Cahawba was left desolate and decaying – the Old Cahawba Archaeological Park protects the site today.

Hirta, St Kilda, Scotland, UK

Martin Payne/Shutterstock

Northwest of the Scottish mainland, the St Kilda archipelago is scattered in the North Atlantic, and its largest island, Hirta, was once home to a hardy population. Bronze Age-era relics have been discovered over the decades, so it’s thought that humans could have been on this island as far back as 5,000 years ago. But the last of them left in the 1930s.

Hirta, St Kilda, Scotland, UK

Joe Gough/Shutterstock

Life on remote Hirta was hard: winters were severe and residents survived only by hunting seabirds. Tourism eventually increased too, leading to vain attempts to modernise the traditional island: frail contemporary homes, much flimsier than the locals' hardy stone huts, were built here in the name of progress. But they ultimately couldn’t withstand Hirta’s ferocious weather. By the 1930s, the last of Hirta’s residents vacated the island, leaving behind their wind-beaten hamlet. Today Soay sheep roam between the remnants of the islanders’ stone houses, as seabirds circle overhead.

Pripyat, Ukraine

Oriole Gin/Shutterstock

Pripyat, in northern Ukraine, was once a buzzing industrial city of around 50,000 people – a home for those working at the Chernobyl nuclear power station and their families. But disaster struck on 26 April 1986. The power plant’s No. 4 Reactor exploded during a routine safety test, leading to a devastating fire and choking out dangerous radioactive chemicals.

Pripyat, Ukraine

Pe3k/Shutterstock

The hazardous radiation killed numerous plant workers, and the residents of Pripyat and the surrounding areas were forced to flee. The city they left behind now exists like a chilling time capsule, with tiny chairs scattered in classrooms, peeling posters still left on walls, and forgotten dolls strewn on rusting beds. The creepiest site of all is the Pripyat Amusement Park with its creaking Ferris wheel and bumper cars.

Silver City, Yukon, Canada

davidrh/Shutterstock

A typical gold-town-turned-ghost-town, Silver City, in the southwestern reaches of the Yukon, was built up in the early 20th century. There was a roadhouse, police barracks, and cabins here in the 1900s, and their remnants are still collected on the banks of Lake Kluane today. The prospectors, however, are long gone.

Silver City, Yukon, Canada

davidrh/Shutterstock

Instead, Mother Nature has been making serious grounds in this ghost town. Rabbits and squirrels skit between the abandoned trucks and decrepit homesteads, and Yukon fireweed grows up in mid-July through to September. In winter, the century-plus-old cabins sigh under the weight of thick snow.

Humberstone and Santa Laura, Chile

Jess Kraft/Shutterstock

Chile’s Atacama Desert is one of the most otherworldly places on the planet: so stark and dry and desolate that it’s used by NASA scientists as a stand-in for Mars. Still, that hasn’t stopped humans from making their home here over the centuries. In the midst of the desert are the ghost towns of Humberstone and Santa Laura, former saltpeter ("white gold") mining settlements that were built up in the 19th century.

Humberstone and Santa Laura, Chile

Jess Kraft/Shutterstock

There were some 200 saltpeter works here in the region’s 19th-century heyday, and a community with a rich culture called the area home. But the industry began to fold during World War One and the mines closed for good in the 1960s. The people dispersed and today the desert ghost towns are strewn with reminders of both a thriving industry and a tight-knit community: still here are the remnants of a railroad, industrial buildings and machinery, and a town square lined with former businesses.

Craco, Italy

ValerioMei/Shutterstock

Cascading over a hilltop in Italy’s Matera province, Craco is quite a sight. It seems almost to blend with its surroundings, its windowless buildings the same colour as its craggy perch. But though it looks at one with the wilderness now, Mother Nature hasn’t been kind to Craco over the centuries.

Craco, Italy

Massimiliano Marino/Shutterstock

A plague gripped Craco in the 17th century, killing a significant portion of the population. Given its teetering clifftop location, Craco was also prone to landslides and a series of devastating disasters throughout the 20th century caused the town’s final steadfast residents to leave. Now the crumbling buildings are abandoned, save from the handful of religious festivals that take place here each year.

Gwalia, Western Australia, Australia

bmphotographer/Shutterstock

At its peak in the late 19th century, around 1,200 people lived in this town, which was centered around one of the largest gold mines Down Under: the Sons of Gwalia mine. But when the mine packed up, in 1963, so did the residents and, in a flash, the thriving town was home to just 40 people.

Gwalia, Western Australia, Australia

Sally Robertson/Shutterstock

Rusted cars and deserted miners’ cottages dot the desert floor, along with the mine manager’s house, a hotel and a series of industrial mining businesses. There’s also a bed and breakfast and a museum housing relics left behind in the one-time boom town, from kitchenware to mining tools.

Glenrio, Texas/New Mexico, USA

Svetlana Foote/Shutterstock

The town of Glenrio was once a road-trippers paradise: pitched as it is across the border of Texas and New Mexico, it broke up the sprawling desert plains and served as a respite stop for those driving the historic Route 66. This dinky town had bars, restaurants, lodgings, and gas stations – everything a weary Mother Road traveler could need for a night. However, Glenrio’s fate changed in the 1970s when major Interstate 40 bypassed it.

Glenrio, Texas/New Mexico, USA

Svetlana Foote/Shutterstock

As scores of motorists no longer parked up in Glenrio, residents left and businesses closed. Now it remains a creepy ghost town with plenty of nods to its past life. Battered signs still advertise long-abandoned motels and cafés, and an empty diner and gas station sit alongside the shells of unidentified buildings.

Kolmanskop, Namibia

Juergen_Wallstabe/Shutterstock

Rusted bathtubs and homes filled to the rafters with sand: this is the modern picture of Kolmanskop, a one-time diamond-mining town in the midst of the Namib desert. The precious jewels were discovered at the beginning of the 20th century, and by 1912 a mining town had mushroomed. At its pinnacle, Kolmanskop comprised a hospital, food stores, bars and even a concert hall, but this diamond-encrusted town soon lost its sparkle.

Kolmanskop, Namibia

Kanuman/Shutterstock

The land was aggressively mined and its treasures soon depleted. By the 1930s, Kolmanskop’s jewels were gone and its residents got word that richly stocked diamond fields had been discovered to the south. They wasted little time abandoning the desert town, and by the 1950s it was deserted. Today a huddle of sand-pillaged buildings is all that remains.

Vorkuta, Russia

Anna Krivitskaya/Shutterstock

The easternmost town in Europe, Vorkuta was once a thriving city in the Komi Republic (a federal subject of Russia), just north of the Arctic Circle. Substantial coal fields were discovered here in the 1930s and the origins of the city are closely tied to Vorkutlag, one of the most notorious labor camps of the Gulag. The city and the surrounding areas boomed until the large-scale mining stopped along with the collapse of the Soviet Union.

Vorkuta, Russia

Anna Krivitskaya/Shutterstock

The mines were quickly privatised in the 1990s but proved to be incredibly expensive to run so started shuttering their doors one after the other. The residents slowly abandoned the city and while reports say there were still around 50,000 residents living in central Vorkuta, the surrounding suburbs, like the Sovetskiy district (pictured), are completely abandoned.

Villa Epecuén, Argentina

De Visu/Shutterstock

Established in the 1920s, Villa Epecuén was a tourist village, established to make the most of the salty waters of Lago Epecuén. Soon the town boasted a railway station and many hotels, lodges and guesthouses accommodating as many as 25,000 visitors at any time. The lake was said to have healing properties so was a much-loved holiday destination, especially by wealthy Buenos Aires' residents. That is, until disaster struck...

Villa Epecuén, Argentina

Sebastian Jakimczuk/Alamy Stock Photo

On 6 November 1985, a seiche (a standing wave in an enclosed body of water) broke a nearby dam, which flooded the town with 33 feet (10m) of water at its peak. The water only receded in 2009, uncovering buildings totally ruined or encrusted in salt due to the high salinity of the water.