The Doors: ‘Jim Morrison had a pretty tough Oedipus complex – it made him manic depressive’

Doors drummer John Densmore is pointing over his shoulder to two royal blue LA street signs situated next to his drumkit. The signs say Densmore Av and Morrison St. “You’re probably curious about that?” he says. “I knew there was Densmore Av in The Valley. I drove by it many times. A few years ago, I thought, ‘I’m going to go up Densmore and see what I can find’. I drive up a mile and it crosses Morrison St. These streets were probably named hundreds of years ago.” He cracks a smile. “Kinda prophetic, huh?”

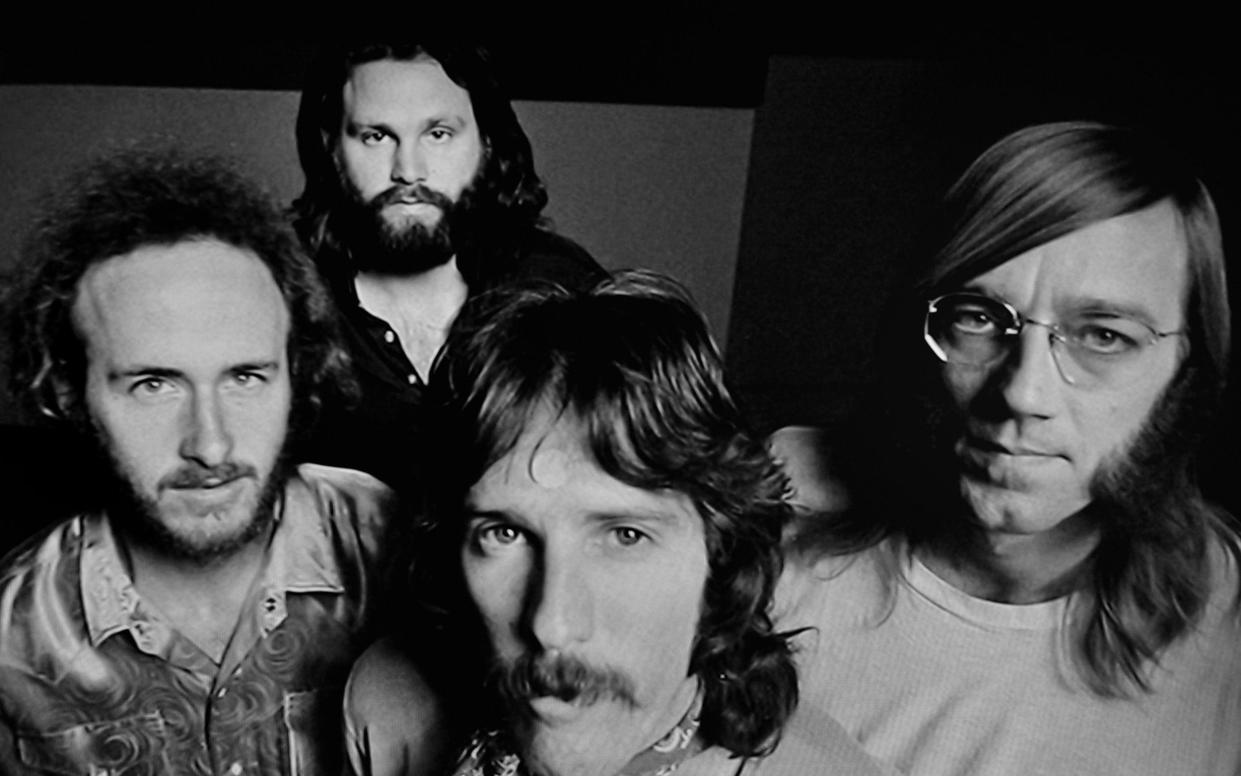

Much of what surrounds The Doors feels, and has always felt, rather prophetic. Jim Morrison’s mystical musings, tousled good looks and bourbon-soaked baritone left its mark on the map of American culture long before he died in Paris, July 1971, at the age of 27. Over the course of six albums in five preceding years, the Doors had diced up jazz, blues and rock and roll to stunning effect, becoming the first American band to rack up eight consecutive gold or platinum LPs in the process.

This year marks 50 years since their final outing as a four-piece, LA Woman, was released. A deluxe edition will commemorate the anniversary on 3 December boasting 17 alternate versions and outtakes in the most expansive reissue yet. On 4 November, a worldwide cinema event will also showcase their historic 1968 Hollywood Bowl show. Cinemagoers will be greeted by an additional treat. “Robby Krieger and I went into his studio a few months ago and recorded LA Woman and Riders on the Storm,” reveals Densmore.

Doors’ guitarist Robby Krieger joins separately over Zoom. A couple of black Gibson Les Pauls vie for space alongside classical guitars placed casually against the wall behind him. Krieger is more softly spoken than his drummer, and talks a few knots slower than the rat-a-tat-tat of Densmore’s Californian burr. Both provide cracking company – open to any topic, and self-effacing too. Following keyboardist Ray Manzarek’s passing in 2013, they are also the last men standing from the seminal US group.

They remember the Hollywood Bowl show clearly. “Jim f__in’ took acid and didn’t tell the band!” Densmore says, still outraged 53 years later. Krieger is more diplomatic – he says he “can’t remember” if the singer told his bandmates about the acid drop prior to walking onstage. “I didn’t think it was that good an idea. That was also the only time we hired a film and sound crew to record a show. That was pretty stupid of us! But I’m glad we did it as it came out pretty good in the end.”

Whilst band consensus may have been that Morrison had been acid-tripping the light fantastic that night, apocryphal stories claim otherwise: Morrison’s spaced-out behaviour being the result of witnessing Mick Jagger with Pamela Courson, Morrison’s long-term girlfriend, on his lap in the front row. Densmore dismisses the notion. “Rumours don’t only gather moss, but B.S.,” he quips. “I couldn’t tell if Pam was on his lap, but Mick was there, and we wanted to play real good. It made me play stronger. I really pushed it that night.”

The Doors emerged from Los Angeles in the basin of Southern California in 1965 and immediately shot to fame. They sounded unlike their peers and unlike anything that had come before — the group’s output chimed perfectly with an experimental era in which university campuses questioned social convention and conservative politics, while heads were cocked collectively to all things ontological. The Doors provided spiritual music for a spiritual age.

The band toyed with the rigours of the pop playbook thanks in part to their frontman’s relationship with mind-altering substances. Densmore also credits revered Indian sitarist, and friend-of-the-Beatles, Ravi Shankar, after he and Krieger attended Shankar’s Kinnara School of Indian Music. “We were exposed to ragas,” he recalls, “and they influenced us to stretch out. Expanding our consciousness and breaking the three-minute barrier felt great.”

A stint as the house band at Sunset Strip’s legendary Whiskey a Go Go also helped. It was here that they pulled at the corners of Krieger’s soon-to-be-ubiquitous, mega-hit, Light My Fire. What started as a taut three-minute pop song turned into sprawling, six-minute opus: “That happened to a lot of our songs,” says Krieger.

By the time the band’s self-titled debut was recorded, their record label, Elektra, sensed that they were onto something big. Above the Chateau Marmont – the legendary hotel on LA’s Sunset Blvd – a huge billboard announced the Doors’ arrival. When the album hit the shelves in 1967, tracks such as Light My Fire, Soul Kitchen and Break on Through (To the Other Side) became radio staples.

Less radio friendly was the album closer The End, a brooding, raga-tuned, 11-minute epic stuffed with explicit lyrics. The suggested meaning of the lyric “Father?/Yes, Son/I want to kill you/Mother, I want to…” was hardly opaque. But was it autobiographical?

“He had an Oedipus Complex,” affirms Krieger unequivocally. “This is what came out in The End. According to Freud, everybody has one, but most don’t recognise it. With Jim, it was right on the surface. He would tell me that sometimes when he was on acid, he would look at the moon and see his mother’s face. That’s a pretty tough Oedipus Complex, right there.”

Was it something that Jim was consciously aware of? Krieger believes so. “I don’t think there was anything he could do about it though. I think it drove him to be manic depressive. When a guy drinks so much that he can’t remember it the next day, it’s often a [symptom of] manic depression.”

Father and mother issues or not, Morrison soaked up the flashbulbs, fandom and attention that came his way like a magic sponge. He seemed made for it. If the others were jealous, they hid it well. “When the first album came out, I used to think, ‘why the f__ is his head so big and mine so small?” and then I thought, ‘oh well, he is pretty good looking,” says Densmore. “Then I realised that the spotlight on a lead singer is so bright, it’s dangerous. I was on the side. I just got singed a little.”

Hallucinogens had taken their toll on Morrison during the writing for third album, Strange Days. Acid had been substituted for alcohol and the booze made him a moodier man. Densmore broke out in rashes and headaches during the album that followed, The Soft Parade, thanks to the conflict it could create. His drinking problem had become the “elephant in the room” according to the drummer, and the group were powerless: “Ultimately, you can’t get anyone to change. They have to want it.”

Live performances became increasingly erratic too. Riots often ensued and Densmore lobbied unsuccessfully to get the band off the road. On 1 March 1969, whilst onstage in Miami, things took an even more perverse turn. A confrontational Morrison labelled the 10,000 crowd “a bunch of f_ing idiots”, clutched a live lamb to his chest, proclaiming he would “f__ her, but she’s too young”. Then, as the band tore through a ragged Love Me Two Times, Morrison fell to his knees before Krieger’s Gibson SG and mimed fellatio. The local newspaper the next day, the Miami Herald, added a further charge to the mayhem: Morrison had indecently exposed himself.

A frenzy followed. Legal documents were shuffled, signed, and served. Concerts were cancelled. Despite any corroborating photographic evidence to back the paper’s claims, the band were out of favour – Morrison pilloried as counterculture’s shaggy libertine. In September 1970, the case against Morrison went to trial. He was found guilty of indecent exposure and “open profanity”, sentenced to six months in prison and fined $500. Although appealed and freed on a $50,000 bond, the court case loomed large when the band stepped into the studio that December. Things were tense. “Jim was on trial for the Miami thing. We were all a little worried, and Jim was drinking more than usual,” recalls Krieger. Even so, Morrison quickly became absorbed in the approach the band were taking. The group would produce this record themselves with trusted sound engineer, Botnik. The album would become LA Woman.

For the first time, the band also recruited a rhythm guitarist, Marc Benno, to join them in the studio. This freed up Krieger from the burden of overdubs and allowed the band to jam more freely. An outcome best exemplified in the songs that both Krieger and Densmore pick as their favourites from the record: LA Woman and Riders on the Storm.

“LA Woman was just a big jam and Jim threw the words on top. That song is just perfect for driving down the freeway,” says the drummer. As for Riders on the Storm, the band had been messing around with the Ventures’ version of Ghost Riders in the Sky when it morphed into Riders on the Storm. “I had that surf guitar kind of sound,” remembers Krieger. “Jim changed the words from Ghost Riders in the Sky to Riders on the Storm. The same kind of thing but so much cooler, you know.” The whole recording process was very laid back. “To use a current term, it was organic,” says Densmore, who titters as it dawns on him that ‘organic” is a term often attributed to food these days. “It’s a vegan record!”

The band also enlisted Elvis Presley’s bass player from his TCB band, Jerry Scheff, who added a thick bottom-end that suited the raspy-throated Been Down So Long, the James Brown funk of The Changeling and more. The only contention is that Morrison wanted it to be an all-blues record. “He was really getting into blues during that time,” Krieger remembers. “One day, we said, ‘Okay, on Tuesday, it’s going to be ‘Blues Day’. He was really excited. And then Tuesday comes around, no Jim. We can’t find him. We couldn’t believe it. He missed the big day. I can’t remember where he was. Obviously, he found some girl or something.”

A fair chunk of the album did satisfy Morrison’s wishes, yet it also branched out, offering textures that resonated beyond a single genre. LA Woman was a huge critical and commercial success, breathing new life into the group and signposting where they might head next. It proved to be a case of what might have been. “Jim was heading towards alcoholism for years,” says Densmore matter-of-factly. “But with LA Woman, [the group] had more control. Jim felt that and stepped up. Also, he knew we were putting stuff down on tape, it’s going to be around for a long time and so you’d better be together. And he was together…for most of it.”

Krieger agrees. “With some of the other records he would just get bored and go get drunk. But he was living across the street from the studio, and he was over there every day. He was really into it. Had Jim come back from Paris, I think we would have made other albums in a similar way because, apart from the first one, that was the most fun.”

Sadly, three months following the album’s release, on 3 July 1971, Morrison became the latest star to adhere to a worrying new trend befalling rock’s golden generation: like Jimi Hendrix and Janis Joplin, he was dead at 27. Morrison’s body was found in a bathtub in an apartment in the French capital. No autopsy was performed, but official records put it down to heart failure.

It’s hard to think of any other band who, having lost their talisman so prematurely, has been subjected to such third-party mythologising. Maybe only Kurt Cobain comes close — even his death, however, comes over 20 years after Morrison was interred in Paris’s Père Lachaise Cemetery. It was one of the reasons why Krieger was compelled to write his memoir, Set the Night on Fire. “There’s a lot of stuff in that Doors movie and some of these books that are out that just aren’t right. I wanted to set all that straight.”

Oliver Stone’s 1991 film starring Val Kilmer has long been a contentious topic. The surviving members looked on horrified as Stone transmogrified Morrison from wayward, mystical shaman to a self-centred, violent drunk. “There’s one part in the movie where Jim pushes Pam [played by Meg Ryan] into the closet and sets it on fire. That was total bullsh_t,” seethes Krieger.

The guitarist worked with Stone on set but wasn’t there the day they shot that scene: “I certainly would have said something. It was a Hollywood movie, and Hollywood movies take liberties by trying to make things bigger than they were.” That said, Krieger admits that the film helped expose the group to a new audience and that, despite its faults, rates both it and Kilmer’s performance: “I thought Val was amazing playing Jim”.

“I used to be asked, 'if Jim was here today, would he be clean and sober?’ Densmore concludes. “I used to say, ‘Nooo, he was a kamikaze drunk’. I’ve changed that answer now. Because it’s a different time. It’s cool now [to be get help and be clean]. Maybe he would get his sh_t together. He’s always an example of going too far. That’s why I’ve been careful.”

If Robby could meet Morrison again, what would he say? A silence fills the air. “I’d say, ‘Why 27?’” Krieger is then momentarily motionless, exhibiting the pensiveness of someone thinking long and hard about an old, dear friend.

“I think he kind of did it on purpose,” he offers, finally. “It seemed like he wanted to be number three after Jimi and Janis. He said that. We didn’t believe him at the time. There was something in him…he was just so interested in death. I thought it was just a game he was playing” He pauses one more time. “But maybe not.”

The Doors: Live At The Bowl ’68 Special Edition will be screened in cinemas globally for one night only on November 4. Tickets are on-sale at TheDoorsFilm.com