Don’t Worry Darling speaks to – but misunderstands – the horrors of the ‘tradwife’ phenomenon

It’s difficult to remember a time before I knew about Don’t Worry Darling. It feels like it has always existed; like it was here before everyone I know was born; like it is more ancient than time itself. And yet somehow the gossip juggernaut only landed in cinemas this week. In the haze of puzzling behind-the-scenes drama, red carpet antics and endless Twitter clips of Harry Styles trying to out-act Florence Pugh (bless him), one thing has got a bit lost, and that’s the actual film itself. Discussion about it seems to have boiled down to two fairly pedestrian questions: is Don’t Worry Darling any good, and is Harry Styles any good? Surely, though, it’s more interesting to ask what the film is trying to say about the contemporary moment. Because, behind the haze and hype, Olivia Wilde’s movie is about fantasy and the dangers of nostalgia. It’s about feminist backlash and alt-right male anger. It’s about tradwives.

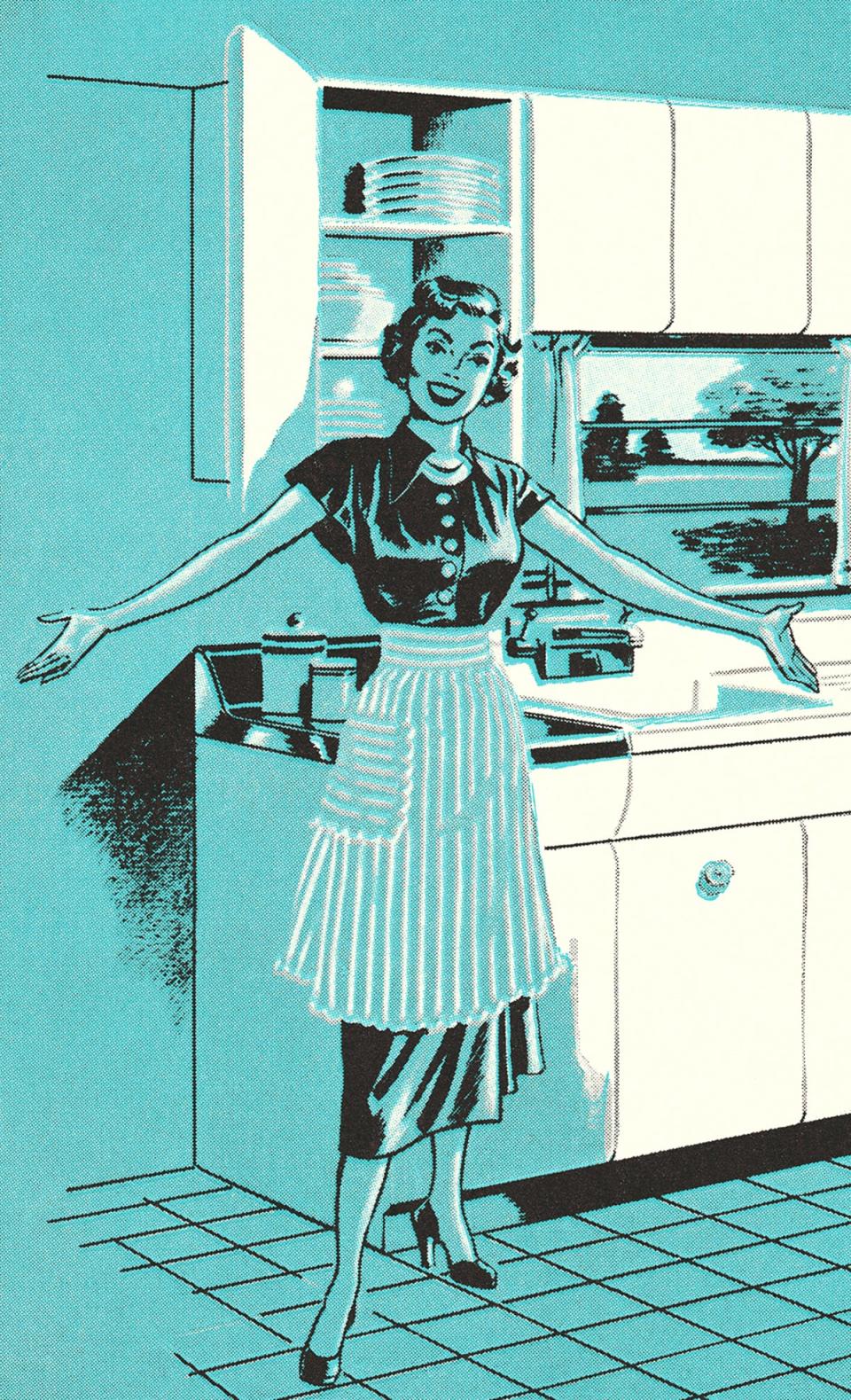

A procession of sexy pastel cars pulls out from a cul-de-sac. In the cars: men in suits. In the driveways: a parade of dolls, plumped, cinched and blowing kisses. Eggs and bacon in frying pans, a fresh pot of coffee, a bit of hoovering. Oral sex on the dining table when hubby gets home; an orgasm near the roast beef. How steamy and delicious, what a dream. On the lustrous, high sheen surface, Pugh’s Alice and Styles’s Jack are living the picture-perfect all-American mid-century life. In the desert enclave town of Victory, they are – according to their enigmatic and glossy leader Frank (Chris Pine) – embarking on an exciting and progressive exploit. And so, the women stay home, while the menfolk head off for jobs at the mysterious Victory Project, where they make “progressive materials”.

Except, of course, modern filmgoers have consumed enough media by now to know that America’s palm-tree cul-de-sacs always hide uncanny horrors, that suburbia is a suffocating trap (I won’t use the word “Lynchian”, but you all know I’m thinking it). If anyone was in any doubt, Wilde’s direction spells it out for us. In one scene that is sure to delight anyone with an autoerotic asphyxiation fantasy, Alice wraps her whole head in cling film; in another, she is suddenly squeezed between a wall and the glass sliding door she cleans every day, both pressing tighter and tighter in a familiar surreal glitch. Do you get it? Her life is stifling! She’s in a gilded cage!

The truth is, Don’t Worry Darling manages to both exceed expectations and fall victim to convention. The first half is luscious and full of potential (thanks largely to Pugh, and Pine’s sinister menace), but the last third slides into cinematic cliché. When the twist comes, as come it must, rather than opening the film up into new, intriguing territories it seems to foreclose all options, forcing the narrative to resolve itself in a typically neat Hollywood fashion. Ultimately, Don’t Worry Darling feels as if The Matrix and The Truman Show shacked up and moved to the upper-class suburb of Stepford, Connecticut. Like these films before it, the horror in Don’t Worry Darling spins around a gulf between fantasy and reality. Here the fantasy stems from nostalgia; from the notion that life was better before.

It is undeniable that this kind of nostalgia is rife at the moment. At the same time Don’t Worry Darling was in production – long before Spitgate electrified Twitter – pockets of the internet kept proclaiming the emergence of the tradwife trend. Short for “traditional wife”, the tradwife promotes ultra-orthodox gender roles in relationships, including “feminine submissiveness” and a cook-clean-sew domestic lifestyle. Essentially, the ideal tradwife is barefoot and pregnant and found in the kitchen. Search the hashtag on social media and you’ll see pictures of pies, flowers and babies alongside florid inspirational quotes: “a woman’s place is in the home”, “trying to be a man is a waste of a woman”, even “it’s healthy for a wife to fear her husband”.

The tradwife has found particular popularity on TikTok. “What is a Tradwife” videos regularly go viral, typically blending defensive arguments about personal choice with explainers on submitting to your husband, and how such a thing “triggers people”. Other videos feature women explicitly contrasting their past lives as “raging feminists [and] ‘Miss Independent’” with their current “enlightened” conservative tradwife state. Some might say being Extremely Online in this way is not very traditional-retro-housewife-anti-feminism-white-supremacy-Xanax, but TikTok tradwives make it work.

Of course, picket fence Fifties fantasies of “the good old days” are nothing new. They are the backbone of conservatism, white supremacy and hetero-patriarchy. But what is remarkable about the contemporary tradwife wave is how its advocates have adopted the language of defiance and individual agency; how conservatives frame themselves as radicals going against a liberal-feminist status quo. In this fantasy, it is the neo-con tradwife and her trad-hubby that are the oppressed minority; the Red Pilled rebels.

Yet to some degree the tradwife trend must be seen as a logical extension of neoliberalism’s toxic potion of individualism and “choice” feminism. It relies on an understanding of human action as governed by individual desires, totally free from the constraining influence of social conditioning. This is how the language of agency and oppression is able to float free of any social facts. Attracted to dominant men? Personal choice. Financially dependent on a partner? Personal choice. Cook and clean and care for children and never complain? My body, my choice. There is no such thing as society.

One woman whose social media promotes “feminine growth” through a hodge-podge of “new housewife tips” (“in married life, the wife is properly the social secretary”) told me she could not comment on what appeals to her about a “traditional” lifestyle, because her husband disliked journalists. But, if he had given her permission to speak, would she have said that “feminine homemaking” was her vocation, as she does in her Instagram captions? Would she have said it was a personal choice, and that serving and submitting to her husband was also serving herself?

In Don’t Worry Darling, the suffocating suburbia Alice finds herself in turns out to be (shock horror) not real. It is, precisely, a gilded cage – a sham utopia designed by and for men who feel out of control and owed attention. The “utopia” is, of course, “no place”. It is a male fantasy; pure misogynistic fabrication. Here, the horror is a lack of choice: women are stripped of agency, and the battle is to regain control. Essentially, the film’s message seems to be that men are bad and all women’s choices are good. If only it was so simple. In the real world, nostalgic fantasy also has swathes of girls in its grip.

‘Don’t Worry Darling’ is in cinemas now