Dolores Huerta and LaToya Ruby Frazier on Finding Their Purpose

LaToya Ruby Frazier’s photographs document the challenges and inequities faced by people across America’s heartland but also serve as calls to action to help address them. Born in 1982 in Braddock, Pennsylvania, a once-bustling steel town near Pittsburgh, Frazier began capturing the profound toll that years of deindustrialization, economic devastation, and environmental abuse had taken on her community while she was still a teenager. Since then, she has continued to create images and videos that provide an intimate window into the lives of her subjects, often spending months and even years with them at a time.

The new exhibition “LaToya Ruby Frazier: Monuments of Solidarity,” which opens on May 12 at New York’s Museum of Modern Art, surveys nearly 25 years of the artist’s practice. For the show, Frazier has reimagined some of her best-known bodies of work, which explore the health-care inequities facing Black working-class communities in the Rust Belt, the water crisis in Flint, Michigan, and the impact of the closure of a General Motors plant in Lordstown, Ohio, in a series of large-scale installations. Each one is what Frazier refers to as a “monument” to the people she has photographed and features first-person testimonials from the individuals who appear in the images.

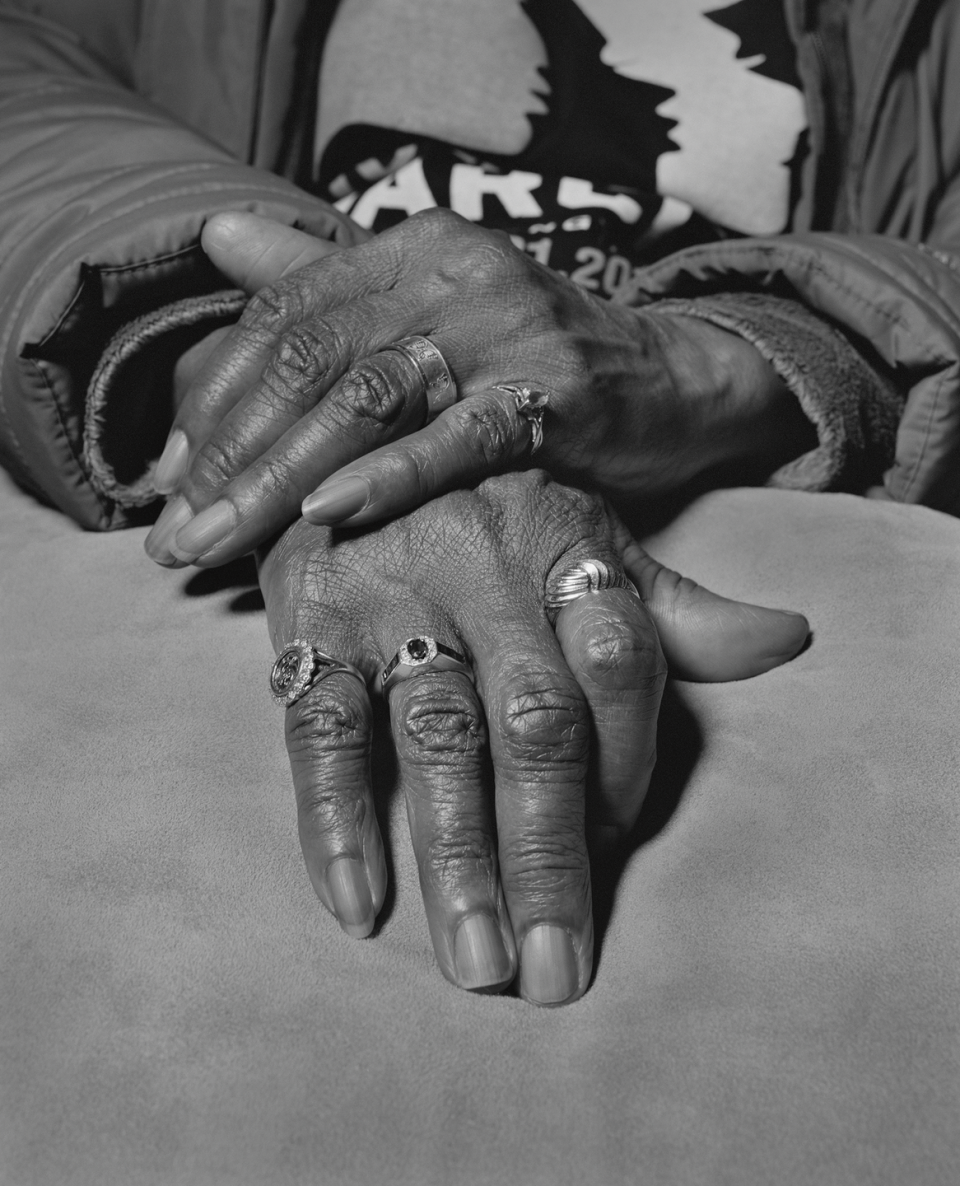

A new body of work in “Monuments of Solidarity” spotlights the legendary organizer and activist Dolores Huerta, whom she photographed in California last year. Now 94, Huerta began, in the mid-1950s, to advocate on behalf of the migrant farmworkers in her own hometown of Stockton, California. In 1962, with fellow labor leader and Civil Rights pioneer Cesar Chavez, she cofounded the National Farm Workers Association, which eventually became the United Farm Workers labor union. Huerta would go on to play a pivotal role in the 1965–1970 Delano, California, grape strike and boycott, which brought nationwide attention to the exploitation of farmworkers. Ultimately, her efforts helped more than 70,000 such employees in that state gain basic rights such as access to bathrooms and drinking water while on the job, as well as higher pay, protection from harmful pesticides, and funded health-care plans.

Top images: Dolores Huerta Standing at the United Farm Workers of America, The Forty Acres, Delano, CA 2023 ; LaToya Ruby Frazier.

In the decades that followed, Huerta worked alongside Gloria Steinem to champion intersectionality in activism; campaigned for women to get elected at the local, state, and federal levels; organized voter-registration drives and health clinics; and fought against racism and police brutality. In 2003, she founded the Dolores Huerta Foundation, a community-building nonprofit that organizes and develops leaders at the grassroots level. It will break ground on the Dolores Huerta Peace and Justice Cultural Center in Bakersfield, California, this year.

Frazier and Huerta reconnected recently to discuss the intersections and confluences of their work and why creating meaningful change is a lifelong endeavor.

LaToya Ruby Frazier: There is a portrait of you that I saw while looking through the archives of Walter Reuther, who was the president of the United Automobile Workers [1946–1970], at Wayne State University in Detroit. You were at a march with Robert F. Kennedy in Delano, California, in 1968. I was struck by it; I'd never seen these types of images of you. Then I came across other images that connected John F. Kennedy and Robert F. Kennedy to Martin Luther King Jr. and Walter Reuther and [the late Civil Rights activist and U.S. Representative] John Lewis. I just thought how shocking it was for me, being born in the 1980s, to never have been taught about the work that you and others like you did in school. We didn’t learn about your contributions to the labor movement in U.S. history or in our economic classes. That image lit a fire under me to then want to go to the former United Farm Workers headquarters in Delano.

Dolores Huerta: I want to thank you for even thinking about farmworkers. During the pandemic, there was a lot of talk about essential workers—the health-care workers, the auto workers, the policemen, and the firemen—but hardly anybody talked about the farmworkers. They grow crops, harvest them, and do all of the hard work that keeps everybody in our society fed. So many farmworkers died during the pandemic because they didn’t get the type of support that they needed. The one thing that we all learned during the pandemic is that we must be connected. In order to survive in our society, especially in times of crisis, we have to support each other.

I have been with many photographers over the years, during the civil rights movement, the farm workers movement, et cetera, but I have never seen any photographer that is so absolutely thorough in the work that they do as you, LaToya—you leave no stone unturned. Not only were you interested in farm workers of color, but you wanted to know about the Okie farm workers that John Steinbeck wrote about [in The Grapes of Wrath]. You visited the actual site of where The Grapes of Wrath movie was filmed, at the labor camp in Arvin, California, and went through every single picture and all of the artifacts that many of the people left behind. I have never seen anybody function the way that you did.

LRF: I was born and raised in the most historic steel town in America. So I have a reverence for workers, working class people, their families and their communities, and what happens to their basic human rights as social and economic policies impact the direction of our nation. There is no avoiding that for me, but it makes me really devoted to uplifting them through my creative gifts. I've devoted my practice to this for over 25 years.

It’s my belief that if U.S. history celebrates industrial capitalists and politicians, then surely we must and can honor workers and their descendants—in particular, activists who diligently fight for workers’ rights and human rights and civil rights. That’s a real message in the MoMA show—and in my work and practice and daily living. That’s an intrinsic value for me. We know that famous image, Migrant Mother, that was created by Dorothea Lange [in 1936 at a farm labor camp in Nipomo, California, when she was hired by the federal Farm Security Administration to travel across the U.S. and document migrant farm laborers to help assess the effects of government programs]. The photograph has Florence Owens Thompson in it with her children, but when I looked at it as a teenager, what I actually saw was a structure of power. The government sits at the top, the corporation is second, the commissioned photographer is third, and the sitter, or the subject, is fourth. I’ve been trying to invert that power structure, and this monument [in “Monuments of Solidarity”] for you, for your family, for your children, and for your grandchildren does exactly that. You and your family are speaking in the first person through your own testimonies about the history of labor and what you have sacrificed for this country. Even more importantly, it honors you as a mother, as a grandmother. The photographs and the monuments within the exhibition also raise resources for the people who are in them. The work literally becomes the platform to generate social justice, as well as raise awareness about these stories and people's lives. I think that's where it dovetails nicely with the work of the photographer Gordon Parks, who also worked with Dorothea Lange on that same assignment, but used his camera as a weapon against racism and bigotry. That's where I'm adding to this legacy in a very unique way.

DH: I want to thank you for including my family in your photographs. I owe a lot of my community involvement and civic participation to my mother, Alicia Chávez. She was an entrepreneur and worked two jobs until she was able to save enough money to start her own business. She had a restaurant before World War II. That’s when one of her Japanese friends was sent to an internment camp and asked my mother to take over her business, which was a hotel. She also set up the first Hispanic chamber of commerce in Stockton and was involved in voter-registration drives. She was very charitable and paid for some of my friends to go to Girl Scout camp. But I never knew that until after she passed away. Often women believe that we can’t get involved in civic life and movements because we have a family life. But women need to know that it’s not only okay but also our responsibility to get involved. Our families will survive. All of my kids grew up in the movement. Because of that, they were very, very resourceful and independent.

LRF: People who are new to my work might think I'm just making photographs and telling stories, but that's the byproduct of what I'm actually doing. I'm really organizing, but through the process of making portraits, still life’s, and landscapes. Then I do storytelling with the people that appear [in the images] to contextualize and foreground that story. In my research, in looking at what I viewed as an oversight of your contribution to labor history, what drew me to it was the Delano grape strike and boycott. That strike, historically, is the most diverse organized strike to ever happen across the country. It was happening in major cities all around the U.S. There were Black, white, Latino, and Asian people involved and so many different activists and organizations believing in what you and Cesar [Chavez] were saying. It was a major triumph to stop the inhumane treatment of farmworkers, so it inspired me. It made me hold myself accountable. That is what I’m trying, as an artist, to visually convey to this generation. If we want real democracy, if we want real change, then we have to do it through unity and solidarity.

DH: Before I was an organizer, I was a teacher. I’d met this great organizer named Fred Ross Sr. During the Depression, he was recruited to become the manager of the farm labor camp that was set up in Arvin, California, which is where parts of The Grapes of Wrath were filmed. I was fortunate enough to go to a meeting with Mr. Ross, and I learned his method of grassroots organizing, which involves meeting in people’s homes and making them understand that they have power. Many of my relatives thought I was crazy to give up my job to start being an organizer of farmworkers. But it was the greatest decision I ever made because I learned how to develop my organizing skills and used them to build a union and go to New York to organize the grape boycott. We had farmworkers go to all of the big cities: Chicago, Houston, Philadelphia. They spoke to labor unions, churches, and any community groups that would listen to get people to picket stores and support the boycott.

LRF: One of the portraits [in the MoMA show] is called Dolores Huerta and Fred Ross, Sr. Inside the Library at Weedpatch Sunset Camp, Arvin Migratory Camp, Bakersfield, California. You called me into the library to show me a newspaper clipping of Fred Ross Sr., and what was interesting to me is that he was white. You and Cesar [Chavez] are Latino. I'm Black, so you see this work happening across racial lines. I can't stress enough, considering the political climate we are currently in, that it has to happen across racial lines.

DH: If we look back on history, the big political changes we have made happened because we all came together, especially young people. Photographers, of course, are a part of that process. If we think about the end of the Vietnam War, it was the images that brought people’s attention to the injustices our country was committing. That helped solidify and activate the movement.

LRF: In terms of intersectionality, can you talk about the connection between LGBTQIA rights in relation to labor rights, civil rights and human rights?

DH: We're talking about human beings; everyone should be respected. To me, the LGBTQ movement is as important as the women's movement. The idea that people should be respected for their gender and for their own private lives is a big lesson our society could benefit from. The right to abortion is a very important battle also. We need to end discrimination of all sorts, whether it's because of the color of your skin, your sexual orientation, or the kind of occupation that you have. We need to elevate our working people to the same level that we elevate professionals.

LRF: How can youth today take these same concerns about living and working conditions in the U.S. in 2024 to impact legislation?

DH: There are so many jobs that are disappearing, and people are not really getting a sufficient wage to live on for the jobs that remain. Workers in America are not being respected as they should be. We all sit down to eat a meal and never think about the farmworkers and the people who process the food, who put food on our table. We have to change that, so that workers can be respected and compensated for what they do. We have a lot of catching up to do.

LRF: One of the other purposes of this monument is to highlight your foundation. Can you talk about some of your programs?

DH: Through the Dolores Huerta Foundation, we vaccinated about 12,000 people against Covid-19 in different parts of California’s Central Valley. We had canvassers go door to door to show people the documented services that are available to them. We’re continuing to educate people on the importance of voting, advocacy, and civic participation. We were very involved in the 2020 census, registering 94,000 people. We have a great education department fighting racism in our schools. When we organize a chapter, we always ask the people what they want to see improved in their community. In one, they wanted sidewalks and gutters; when it rained, they were having to walk in the mud. An adjacent community had septic tanks that overflowed, but they were able to get connected to the city sewer system. Members also got themselves elected to water boards and school boards. The real story behind this is that people themselves are taking over the governance of their own communities. That is what organizing is all about: to let people know that they have the power to create the solutions to the problems that they have. They may not have a college degree, sometimes not even a high school degree, but they have the power.

LRF: All of my installations come with books that I edit, write, and put together with interviews. I also slip in how-to guides for organizing. In my book The Last Cruze [2020], which was made around my installation of the same name, there are step-

by-step instructions for how to unionize your workplace. I noticed that once The Last Cruze started touring through museums, some museum workers were using the exhibition and book to unionize. At my MoMA show, viewers see The Last Cruze, which includes portraits of the men, women, and children in Lordstown, Ohio, many who were part of the historic United Auto Workers Local 1112, which was known for its wildcat strikes. It’s the centerpiece of the show because MoMA acquired the entire installation.

DH: We have to make more people understand that they, as activists, can participate and help enact the policies we need to make our world better. I like to quote Cesar Chavez, who once said to a group of students, “When you go to school, you write about history, you read about history, you talk about history. But when you become an activist, you make history.”

You Might Also Like