The director who went from selling CDs on the street to an Oscar-tipped movie – in six years

It’s been a dazzling ascent. In 2018 Blitz Bazawule was projecting his first film on to the walls of anyone who would watch it; his second film was a collaboration with Beyoncé.

In 2020 it was announced that he would direct a multi-million-dollar remake of The Color Purple, produced by Steven Spielberg, Quincy Jones and Oprah Winfrey (out this month). All in the space of six years, including the Covid era.

And before that, Bazawule was a successful musician, known as Blitz the Ambassador. Displaying the same kind of drive, he started out selling CDs on the street in New York, and has since toured the world and produced four albums. Oh, and by the way, he also had a novel out last year.

So it’s not surprising that Bazawule’s a bit tired, though it’s more likely because he only arrived from LA an hour ago and here we are already doing an interview in London.

Dressed in a suit and a black hat, he’s a quietly spoken and articulate man, with a demeanour that is part hipster, part elder statesman.

The film that had sparked Beyoncé’s attention was his debut, The Burial of Kojo, a visually remarkable 80-minute elegy about a young girl and her father, shot in Ghana, which made its way to Netflix.

It’s such a beautiful film that it’s hard to believe it was made by a director with no experience, who didn’t even go to film school. Bazawule, now 41, wrote, directed and scored it, but he was learning on the job; his director of photography, Michael Fernandez, had never shot a film either.

‘We were looking on YouTube to ask, “What does a first AD [assistant director] do?”’ he says. ‘All the actors had to learn how to act – none of them had ever been in a professional movie before.’

But he had the vision in his head, and The Burial of Kojo was nominated for 12 awards, winning four. ‘At the time I thought this might be my only chance to make a movie so it had to be a living testament to how I think – because I might not get another shot. It might never happen again.’

Which gave Bazawule a lot of artistic freedom. ‘It came down to what do I like? I like disorienting frames, I like vivid colour, I like deeply emotional but also expansive, wide shots – so let’s go. I didn’t have a producer to tell me not to do things.

‘It wasn’t easy – the film took a lot of work but I’d drawn every frame beforehand. I storyboarded the whole thing.’ In order to raise the funding, Bazawule went out on tour with his band. They played in America and all over Europe and he raised $40,000. Then he went to Ghana to start shooting; the cast and crew were all local.

‘We shot the film and then came the challenge of getting it seen. Having spent this much time and effort on it, it had to be seen. So I started taking it to festivals, and I bought a projector to project it on any white surface I could find…’

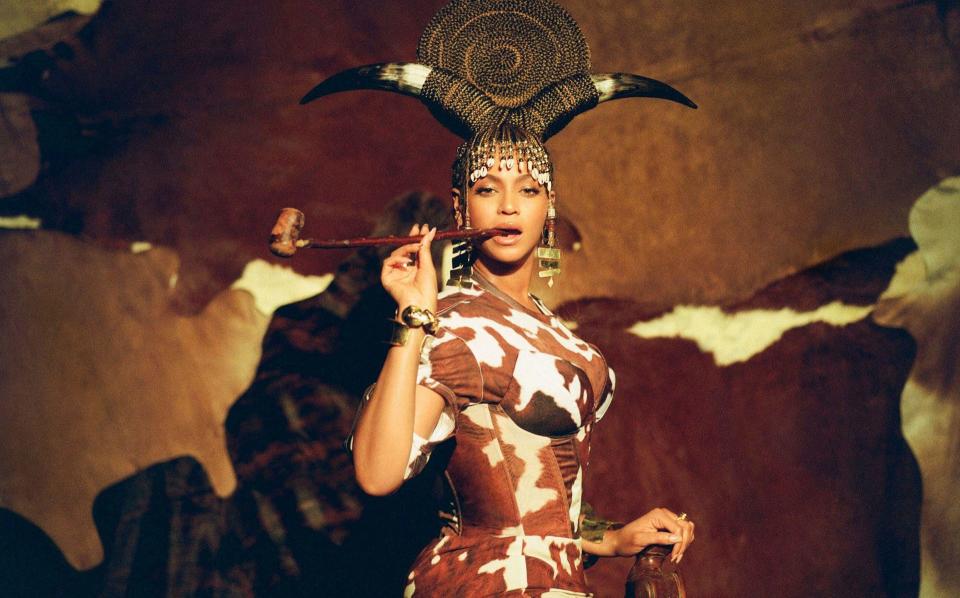

Film director and producer Ava DuVernay (who made Selma and Origin) heard about Kojo and managed to get it on to Netflix. ‘That was a major transitional moment because that’s how Beyoncé saw it, and I got to do Black Is King with her – which gave me the confidence and momentum to put myself forth for The Color Purple.’

So, Act Two: one day in 2019, Bazawule’s music manager called him and said, ‘Hey, I got this email, supposedly from Beyoncé – but it could be spam, it feels very hoaxy.’

The message said that Beyoncé was working on a project, had seen his film and wanted to talk to him. ‘So I told him to just write back. If it’s phoney, it’s phoney, but maybe it’s real.’

It was real. ‘I was in LA anyway so I showed up to see Beyoncé, and they said, she’s not here but she’ll be back tomorrow. Here’s an office if you want to work on your pitch.’

Bazawule was left alone, wondering what to do. He knew that it was to be a visual companion to her new album, The Lion King: The Gift, ‘and I just thought, well do what you know – which is drawing and sketching. First, let’s get rid of the animals and make it human, because the world is socialised to see Africa only through the portal of wildlife, so let’s try and make a human story and imbue characteristics of the lion king on to humans.’

So he got to work, using pencil and ink. Next day Beyoncé didn’t turn up. Nor the day after that or the day after that. By then, Bazawule had quite a lot of sketches. ‘I thought, well, this may not be happening, but I just kept going – sketching, sketching, sketching – until I had over 300 frames.’

A week in, he was getting a drink from the fridge in the communal area when he heard a shout – ‘Bliittttz!!!’ He turned around and there was Beyoncé, barefoot, in an orange jumpsuit. ‘She just gave me a hug and said, “I hear you’ve got something for me!”’ He showed her what he’d done and she said, ‘Go get started. Start prepping.’ ‘She gave me a budget and a producer and we got to work.’

Most of it was shot in South Africa. Were you daunted by the scope of it? ‘No – because we actually had money. I thought, if I can make ideas come alive with no money – and now I’ve got Beyoncé, the biggest greatest artist of our time, and money, and a crew, then let’s go for it.

‘I was trying things out, taking full advantage of my freedom. I did this crazy levitation shot in one of the most insane locations in Johannesburg – it was madness.’ There were other directors on the project ‘but I was the main one who had the spine of the story, which everyone’s story had to fit in with’.

The album and film were released during Covid, so it got a lot of airplay. ‘And then my agent called me about The Color Purple.’

The original film, based on the Pulitzer Prize-winning book by Alice Walker, was directed by Steven Spielberg and had music by Quincy Jones, starred a young Whoopi Goldberg, and featured Oprah Winfrey in her first film role. So that was a fairly intimidating precedent. It was nominated for 11 Oscars, but controversially didn’t win any (though Goldberg won Best Actress at the Golden Globes). It was also adapted for the stage, on Broadway, in 2005, to great success.

Celie is an African-American girl in the Deep South, who is impregnated by her stepfather, has her children taken away and is forced into marriage with an abusive man called Mister. Her greatest friend is her sister Nettie, who disappears from her life. But she is rescued by the glamorous singer Shug Avery, and gradually Celie discovers her own power.

Bazawule had seen Spielberg’s film, which he describes as ‘hallowed ground’. ‘It’s sacred text – my instinct was, if you don’t have anything new to say, then just leave it alone. It’s been a healing force for a lot of people, and I was surprised they were making a new film. I didn’t understand why – remakes make me skittish. I thought, oh man, am I really going to contribute to this trend of failed remakes? I don’t think this is the vehicle for my first studio picture – it can make or break you.’

But the rights had been secured, and there were producers and a script. And the producers were an intimidating bunch – no less than Winfrey, Spielberg, Quincy Jones and filmmaker Scott Sanders.

Bazawule was certainly not the first person they’d approached to direct. He later found out that they’d seen seven directors before him, and had pretty much settled on one, but just wanted to give him a chance.

The challenge was to do something different. There are four books, says Bazawule, that he carries around with him all the time – Toni Morrison’s The Bluest Eye, Gabriel Garcia Márquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude, Isabel Allende’s The House of the Spirits.

And The Color Purple, which opens: ‘Dear God, I am fourteen years old. I am I have always been a good girl. Maybe you can give me a sign letting me know what is happening to me…’

‘I thought, wait a minute. Whoever writes letters to God must have an imagination, and if this is a portal then I’ve stumbled upon something interesting.’

In the original film, Celie is a passive and traumatised victim, but Bazawule’s plan was that she would have a wild imagination which would be her escape. He had some experience to lean into. His mother had been through struggles when he was growing up.

‘When the government was overthrown in Ghana, my dad was in Egypt, and my mum was put in jail because of his affiliation with the previous government: my father had worked for the Ministry of Foreign Affairs.’

Bazawule, who was very young at the time, was looked after by extended family. ‘When she was released I could see her deal with this trauma, and channel it through enterprise and imagination. So when I read deeper into Celie, I could see it. Because I’d lived with a woman who was able to exorcise and cope with trauma. And people who’ve been exposed to trauma and abuse are often categorised as docile – or waiting to be saved. My mum wasn’t like that – to this day, she always has a new scheme, a new idea, a new project. There’s always something she’s cooking up.’

So Bazawule imbued Celie with the same qualities, which is counter-intuitive to how she’s been projected in the past. He gave her agency.

Bazawule got carried away. ‘“We’re going to have this giant gramophone, and a mega orchestra” – the ideas just got bigger and bigger.’ And of course he had done sketches, hundreds of them. ‘Because I deeply believe that you don’t tell, you show.’

It was August 2020. First he was pitching to Scott Sanders with storyboards. He did it all via Zoom, which he had become very adept at. He really knew how to pitch (so much so that Greta Gerwig asked for his advice, and based her Zoom pitch for Barbie on his Color Purple pitch). Then he got a call saying Winfrey would like to hear his take.

He told her about his plan to let Celie’s imagination fly. He told her he was going to go crazy. ‘And she said, “Blitz, I love it! I think Steven should hear this…”’ (Later he found out that she was texting the other producers at the time, saying, ‘I think we’ve found the guy.’)

It was time to pitch to Spielberg. His pitch was ‘visual magic’, Spielberg told The Wall Street Journal. ‘The choice to engage him on this was the easiest choice we made.’

Act Three was beginning. He needed to find his Celie. Fantasia Barrino had played her in the Broadway production and Bazawule had her in mind for this too. ‘A film like this is deeply ensemble, it’s very co-dependent but also central around Celie.

‘Fantasia didn’t want to do it – it was traumatising for her. She herself had been abused as a young girl and playing that role on stage seven nights a week really took its toll. She had vowed not to go near it again.’

So Bazawule looked elsewhere. Everywhere. ‘Self-tapes, friends of friends, actors I’d admired on TV and in the movies, I just kept going. In the end I said, “Fantasia, please let me just tell you about the version I’m going to make.”

I flew down to North Carolina, showed her my sketches and played her the music that we had reimagined – a combination of gospel, blues and jazz – and she was sold.’ It was her first studio film. ‘Later she told me that through making this film she was healed. There is no bigger compliment.’

The film is a visceral whirl of colour, sound, gorgeous landscapes and striking imagery, steeped in music, and the final seal of approval came from Alice Walker. ‘She paid me a visit on set,’ says Bazawule. ‘It was probably the most nerve-racking day ever. She said, “Hey Blitz, I’d like to see what you’ve been shooting.” And I thought, oh boy, what do I show?

‘We landed on a scene where Mister and Harpo walk out of the juke joint and he lays his head on Harpo’s chest and says, “You done good boy.” I hear deep sobs behind me, and I thought, damn, this can only mean one of two things – I’ve either screwed up royally with her beloved text or I’ve made Alice Walker feel something so deeply that she’s sobbing. And she wrapped her arms around me and said, “That’s what I always hoped it would be like.”’

Bazawule grew up in Accra, Ghana. His father worked for the government and then became a civil rights attorney and his mother (Mama Jean) was a schoolteacher. Born Samuel Bazawule (he got his nickname as a rapper in college), he was the third of four children, but a bit of a loner – his older siblings were close in age, and he had a much younger brother.

‘I enjoy solitude,’ he says. ‘It’s a good place for the mind to wander.’ Ghana has a very academic culture, but Bazawule and his brothers and sister were all quite arty. ‘Before music became a part of my life I have always gone back to visual art, no matter what. I always draw my ideas.’

He liked to create things. ‘I broke things, I built things. I am deeply curious – about everything. Any toy I got I would break it open and see if I could put it back together. I often failed, but that’s how I learned about the world. I could always entertain myself – that’s the virtue of a loner.’

His mother encouraged his creative side. She gave him a little corner of the house to play in. ‘I set up a little pseudo studio – that’s where I drew, that’s where I learnt to rap, I learned everything there. I’m transported back to that room wherever I’m in any creative mode. I was free to sit there, sometimes at the expense of doing homework, because she knew I loved it and it kept me close, kept me focused on something.’

Bazawule’s upbringing is central to everything he does. ‘Over time I have learned how to put that stuff into my work and I think all filmmakers are loners essentially. Initially you have to be able to sit there for long hours – to write, to conceive – that’s a very lonely sport and yes eventually you bring other people in and create, but I think any creative mind has to be able to hear that quiet voice.’

He had always loved film. As a child he would go to see evangelical films, which were free and shown outdoors, and the only communal entertainment they had.

‘It was less about the evangelical value, and more about the fact that we could finish our chores, go and sit in a beautiful soccer park and watch a massive screen. And that was my introduction to what an amazing reaction an audience could have to one frame of a film.’

When he was 18, Bazawule went to university in America, at Kent State in Ohio. ‘The assumption was that I would study architecture, because if you’re an African kid that can draw, your parents immediately think, “Architecture, design!”’

He soon realised that wasn’t for him, and ended up studying marketing. ‘I thought, at the end of the day you have to sell whatever it is you’re doing, whether it’s art or not, so I wandered into this marketing class and it was a whole world of magic. I loved those classes – they were about consumer behaviour, and there’s no form of art that doesn’t involve some sort of understanding of consumer behaviour.’

He stuck with that course. ‘Made my parents very happy.’ After graduating he moved to New York and started making music. ‘But I always felt off-kilter. I never did anything mainstream – my music was a mishmash of west African music and Western hip hop and R&B. Now it’s popular – Afrobeat is everywhere – but 15 years ago, it wasn’t a thing. I’ve always had the urge to pick the harder route.’

He would sell his CDs on the street in New York. There was a Virgin Megastore on Union Square, and Bazawule discovered the listening booth. ‘Every time I went in I’d see a long line of people waiting to listen to new albums.’ Hey, he thought, ‘That’s what’s missing… I made a little contraption box thing and took it on the train and set it up on the pavement in front of Virgin, until they booted me out for taking their business. But I sold a lot of CDs.’

He spent the money on going to the cinema. ‘That was my film school. I always had this little notebook – it said “Home Film School” on it and as soon as the lights came on at the end I’d write notes about things I’d seen, camera shots.’ He had a friend at NYU who told him what they were studying and reading at film school, and Bazawule would go to the library.

To have studied music, or film, or art he says, would have felt like ‘a hat on a hat’. ‘I admire people who do that but I also know there is a tendency to flatten your voice, which can happen through the institutionalisation of any medium. Like jazz, for example. Everyone plays jazz the same now. There was a time when Miles Davis was just making it up. Coltrane was making it up.’

One day, in 2015, when the music business had plateaued for him, his mother rang him and said, ‘I have had a vision. And I saw Hollywood. And if you’re thinking of making a film, I think you should go ahead.’

Did you take that seriously? ‘I did! Whatever my mum says I take very seriously – she’s a rare bird. She was not like any of my friends’ mums. She was liberal. My mum is from a small village in the northern part of Ghana, but her acumen and her ambitions far surpassed all that. ‘It’s how I got here. Her ability to let me fly.’

The Color Purple is released on 26 January