A demon Ronald Reagan and money-conjuring gnomes: New York exhibition explores art and conspiracy

Once a week, someone posts to Reddit asking for everyone’s favourite conspiracy theory.

Among the most recent responses, some gems: Elon Musk is a stranded alien who’s only researching space travel to find his way back to Mars, the period AD 614-911 didn’t exist, and the Olsen twins are just one person who moves from side-to-side rapidly to trick the human eye.

In other words, conspiracy tends to be entwined with idiocy - but in one of New York’s most fascinating exhibitions, the Met Breuer explores the interplay between conspiracy and art, and how we perceive the hidden forces over our lives - both real and imagined.

It’s approached in two ways; the first is the curation of artists who’ve created artwork from factual sources, the second is those who’ve delved into the “fever dreams of the disaffected”.

The best example of the latter looms over every visitor on entry - a huge peachy pink portrait of Lee Harvey Oswald glares down right outside the elevator, an enigmatic smirk challenging you to untangle the web of claims and counterclaims surrounding JFK’s assassination.

It gives way to the first half of the exhibition, where facts and data have been turned into artwork. These days, we’d call them infographics - like the conspiracy chart by Mark Lombardi, which maps connections between Bill Clinton and the businessman who pledged $1m to his presidential campaign. It’s beautiful in its simplicity, and the type of diagram you’d see spread across a double-page spread in a printed broadsheet.

The same goes for crisp prints of black sites used by the US by Trevor Paglen - battered-looking buildings used as secret prisons used by Washington agencies such as the CIA during the war on terror to hold and interrogate prisoners away from US soil - images which become even more unsettling when placed in a frame and hung in an Upper East Side gallery.

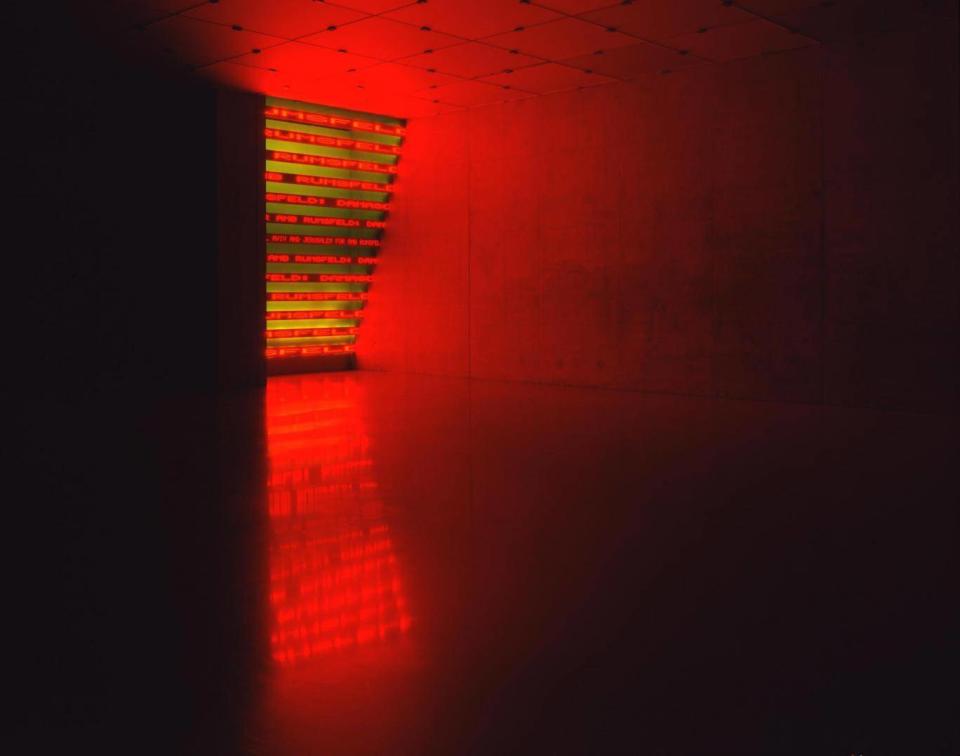

There are Öyvind Fahlström’s boldly coloured cartoon world maps, with commentary, background and diagrams neatly filling each country’s bubble; a trippy installation in which the same Iraq War headline judders along on 13 digital tickertapes, and a vomit-green three-tone image of Ronald Reagan with demon-pink eyes, in response to his AIDS policy.

The second half - exploring the fantastical side of conspiracy theories - is where things get patchier.

There are startling, powerful pieces on the journey down this rabbit hole, like the psychedelic San Francisco landscape by Peter Saul called ‘Government of California’, but some of the on-the-nose offerings feel a little like a sixth-form art project. Examples include an 80s game show scene, with a Wheel of Fortune board spelling out ZOG - a reference to the anti-semitic conspiracy theory that claims "Jewish agents" secretly control the governments of Western states. The contrast between the cheesy upbeat background and the sinister proponents of a such a conspiracy theory is supposed to be jarring, but elicits a shrug. Nearby, there's a framed rectangle of upbeat, floral wallpaper - a hole cut through the middle shows a grinning President Reagan with CIA director William Casey. The symbolism would not be lost on a 10-year-old.

Things are satisfyingly wrapped up towards the exit; a theatrical backdrop - a scene of everyday Americana - is painted over with a sinister blood-red spider web. In the centre is a door, and near-darkness beyond, inviting the visitor to delve deeper, to explore, and to try to make sense of what’s going on.

Spoiler alert; inside, you’ll find some Disney-esque gnomes crowding around glowing orbs, apparently conjuring money from nothing.

Like tugging on the threads of the most compelling conspiracy theories, the discovery yields more questions than answers.

Everything is Connected: Art and Conspiracy is at the Met Breuer until 6 January