In defence of Derby, Britain’s ‘worst’ city

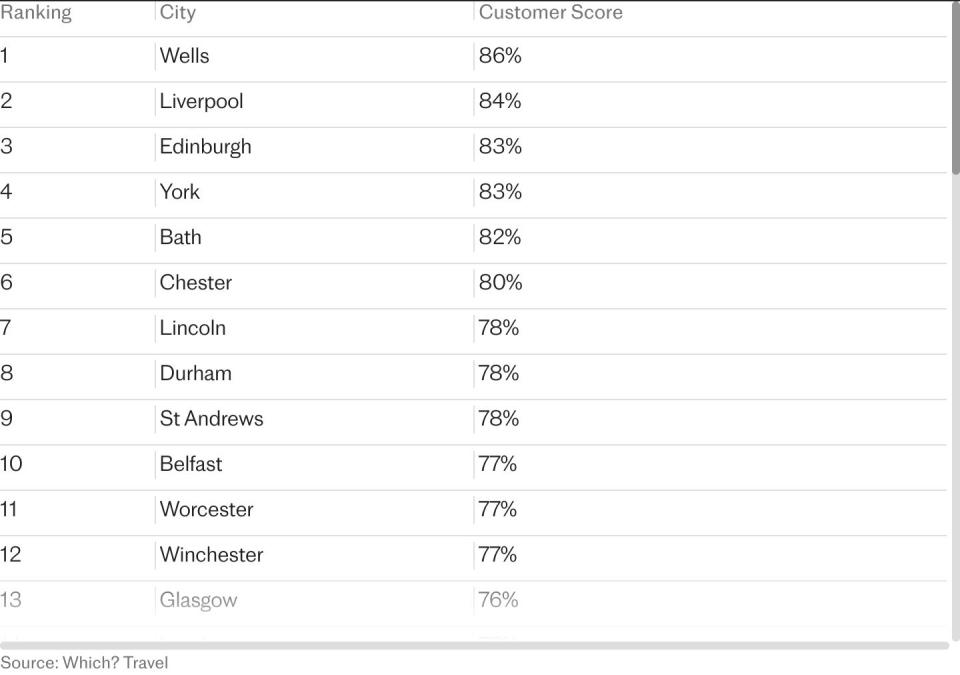

Rankings reflect the prejudices of a moment in time. Which? magazine has placed Derby 25th out of 25 in its survey of larger UK cities (and 62nd out of 62 overall) because those polled awarded it “just two stars for food and drink, accommodation, cultural sights and tourist attractions, shopping and ease of getting around”.

But what about history, local people and alternative sights? Ian Nairn called Derby “that most Midland of Midland towns” and I’ve often thought that the city’s place on the map makes people expect it to be middling, identity-less, neither one thing nor the other. In fact, Derby has a long history, as is immediately evident to the even mildly curious visitor.

The Grade I-listed Cathedral Church of All Saints – occupying an ancient site – has a lofty, square, early 16th-century Perpendicular Gothic tower. The rest was rebuilt in the 18th century and many have compared the interior to that of St Martin-in-the-Fields on Trafalgar Square. As I was once, briefly, employed as a verger at the latter, perhaps I have a soft spot for Derby Cathedral. It has the oldest ring of ten bells in the world. Surely that should nudge it up any ranking.

Derby, like many British towns, grew and got dirty and knocked around during the Industrial Revolution. It was in right at the start when Hargreaves, Strutt and Lombe set up a water-powered silk mill in 1717, not far north of All Saints. It’s now the Museum of Making, which one generous visitor in the Which? survey noted was “worth a visit”.

It all depends on what you like, of course, but who wouldn’t want to ogle the world’s smallest engine “run using a human hair” or a seven-tonne Rolls-Royce Trent? Entry is free, except for some talks. Derby Art Gallery, a short walk away, is home to the largest collection of work by Joseph Wright, born in Derby in 1734. His works capture the drama of new technologies, the magic of science and the enduring – and, then as now, threatened – beauty of nature.

Derby has been a powerhouse in aviation, railway and car engineering. The Midland Railway made the city its main node, and the station is still a crossing point for trains between Birmingham, Cardiff, Crewe, Bournemouth and Nottingham, Reading to Newcastle, and for the Penzance to Aberdeen service – the UK’s Trans-Siberian.

It’s just 130 miles to London – the fastest train is 1h 27 mins – and while I’d never want to rate a city according to its usefulness as a brain drain to the Smoke, we should recognise the fact that the Derby-headquartered Midland-built St Pancras station – a classic example of muck in the provinces gifting brass to the capital.

Derby was (and still is) the home of the Rolls-Royce Engineering Company, which designed, built and developed the Merlin engine used to power the Spitfire and Hurricane fighter planes during the Second World War. The Trent turbofan engines that take most of us on foreign holidays are assembled here. The business was incorporated as Rolls-Royce Limited in 1906, and a new factory in Derby was opened in 1908. The buildings on Nightingale Road are listed by Historic England.

Rolls-Royce and Bentley cars have a long history tied to Derby, with Toyotas and gorgeous Paramounts also built nearby. A new museum, Great Northern Classics – based at the former Victoria Ironworks foundry, which until recently served as the Rolls-Royce Heritage Centre – showcases classic cars from all eras.

Derby sits in the foothills of the Pennines. Where Nottingham and Leicester are hardcore East Midland conurbations, with terraces of tough red brick, Derby has more stone and stucco. It would have more still if lots of 18th-century houses hadn’t been pulled down to create a dual carriageway. Nevertheless, countryside is always near at hand, and three sides of the city are dotted with National Trust properties.

The Derwent, which flows through Derby, is best known for turning waterwheels, but it gives the city region spaces for greenery and clean air. Less than two miles upstream is the Darley Abbey Mill. Though this site is in commercial use – Darleys restaurant is in the Michelin guide – it forms part of the Derwent Valley Mills World Heritage Site, the bulk of which lies a further six miles to the north (the train goes there; the Transpeak bus takes you there for £2). A little further to the north are Chatsworth House and Edale, where the Pennine Way begins its northward tramp.

Twelve miles to the southwest is Burton upon Trent, national capital of beer making. Directly south, at the same distance, is Ashby-de-la-Zouch, site of Lord Hastings’ great tower and gateway to the national forest – a 200-square-mile conservation zone that protects millions of trees.

So there’s certainly plenty to see and do. As for food, drink and accommodation, Derby ranked favourably with Nottingham and Sheffield in one 2023 survey of the best places for drinking, thanks perhaps to its 106 CAMRA-approved real ale pubs for every 100,000 people, including a number of award-winning venues. It also ranked sixth in The Telegraph’s top ten cities more recently. There are hotels for all budgets, and a couple can stay in the centrally located Cathedral Quarter Hotel for under £70 a night (half the price of a chain hotel stay in many cities).

There are sushi, curry, Mediterranean, Greek, tapas, pizza, seafood and auteur restaurants galore, cafes, proper local bakeries, delis for sampling Bakewell pudding (different from tart) and Stilton cheese, and hotdogs – which were possibly invented by Derby-born Harry Stevens in 1901 (possibly because he couldn’t pronounce “dachshund”).

There are things missing from Derby’s cityscape, for sure. Post-industrialisation has ravaged all towns that once depended on man, machines and muscle. But Derby is all right. The Midlands is the heart of the English nation, and this old city has been at the centre of everything historical and social and logistical since almost forever. Cast off your metropolitan angst, and have a weekend break there. Overtourism won’t be a problem, nor hipsters, nor £5 coffees, nor £7 pints.