The dark side of George Formby, a ‘dirty little Northern would-be Casanova’

George Formby still holds the record as Britain’s youngest professional jockey, making his debut at Lingfield Park in 1915, when he was just 10. For the remainder of the First World War, he raced in Ireland. His father invested in a prize horse called Philander for his son to ride.

It would turn out to be a strangely prescient name: Formby kept his lecherous private life secret from a public who made him Britain’s most adored showbusiness star of the era.

Formby, who raced under his birth name George Hoy Booth, quit racing after his 45-year-father died of pulmonary tuberculosis in February 1921, shortly after collapsing during a pantomime performance in Newcastle. The teenage Formby quickly decided to follow in his late father’s vaudevillian footsteps, copying parts of his act and adding his own skits as a blackface entertainer who sang minstrel songs and told jokes about parrots. His huge public popularity came later, when he finally invented his own popular persona as the cheeky ukulele-playing ‘Lancashire Toreador’.

Now, 60 years after Formby’s death, it is hard to overstate the level of celebrity the singer-songwriter from Wigan achieved in the mid-20th century. His most famous record, Leaning On a Lamp-post, sold 150,000 copies in just over a fortnight in 1937.

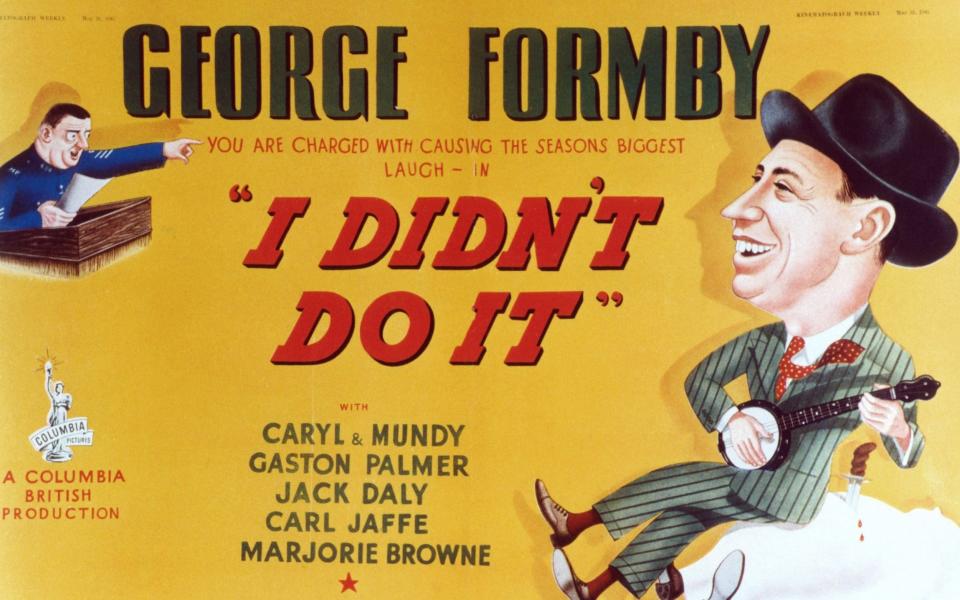

The public just could not get enough of him. Formby made 20 films between 1934 and 1946, when he was British cinema’s leading attraction. The contract he signed with Columbia Pictures in 1941 made him higher-paid than Humphrey Bogart, Errol Flynn and Bette Davis. “He used to get about £35,000 a film – by modern standards that’s about £1,500,000. He was big time,” said lifelong fan Frank Skinner.

The major turning point in his early career came in September 1924, when he married “Lancashire lass” Beryl Ingham, a tenacious clog-dancing champion – a skill that had a poignancy, given that Formby hated the anti-Northern nickname ‘Cloggy’ he’d been saddled with as a youngster by Epsom stable boys. She was four years older than Formby and exerted a controlling influence from the start. Formby later described their tumultuous, largely sexless marriage, as a “living hell”.

Although she guided his career expertly, astutely directing him to build his act around his ukulele performances, even though he could only play in one key and was unable to read music, she was deeply unpopular on the circuit. Actress Irene Handl called Beryl “a nasty, spiteful, twisted, conniving piece of work”, while Betty Driver, who acted with Formby as a teenager and went on to find fame as a barmaid in Coronation Street, described her as “a monstrous woman”.

Beryl shaped his stage image as the good-natured, gormless northerner, always happy to play the clown. He even approved a line in a film describing him as having “a face like a horse and a row of teeth like a graveyard”, and made his buck-toothed grinning shtick his selling point. On screen, his awkwardness around young women became a Formby specialty; his moments of rising panic in any romantic scenario usually punctuated by a yelped cry of his catchphrase, “Ooooh, Mother!”. People loved his squeaky-clean image as much as his squeaky voice.

Actor Timothy Spall, who recreated Formby in his 2016 film Stanley, A Man of Variety, is among those who identified a disturbing hidden quality that Formby shared with other great entertainers of his era, including Max Wall and Noël Coward. “Beneath the appearance of cosy fun and jollity,” remarked Spall, “there was something sinister about their affability.”

Although Beryl kept a lid on the darker parts of the Formby story, some of the elements, including her own affairs with young actors, came to light in David Bret’s 1999 biography George Formby: A Troubled Genius, the most explicit of the five biographies of Formby. “Beryl had her young men; he had his leading ladies,” said the author in an interview.

Bret’s book sparked outrage among the legions of the entertainer’s fans – who call themselves Formbyites – especially diehard members of The George Formby Society, which was founded in the aftermath of the entertainer’s death in 1961. In July 1999, in an editorial in The George Formby Newsletter, the society reacted angrily to the salacious biography, admitting it could be “very damaging” to the society’s image.

“Bret’s controversial book condemns George as a womanising drug addict who had leanings toward homosexuals and sympathy towards Hitler. Beryl was classed as a drunkard, a bag and a cow who had a string of affairs,” the editorial said. To add insult to injury, the society reported that Bret had dismissed their members as a bunch “who walk round wielding Zimmer frames and ukuleles”.

As well as highlighting old family skeletons – including the story that Formby’s grandmother had been a sex worker in Ashton-under-Lyne and that his father George Formby Snr was a bigamist – Bret revealed the extent of Formby’s womanising with dancers and chorus girls, describing how Beryl flew into drunken rages when she heard about Formby’s philandering.

When Formby had an affair with Kay Walsh in 1937, on the set of Keep Fit, Beryl tried to have the young actress removed from the production. When director Anthony Kimmins refused, Formby’s wife went to producer Basil Dean and asked him to have Walsh made look less appealing on screen, fitted out in dowdy frocks and given an unflattering haircut.

Walsh, who married director David Lean three years later, apparently fell for Formby’s “charming flirtation”. Although the public believed in the image of ‘Good old George’, his seedy reputation among the acting fraternity was well known. “He screwed like a tiger until dawn,” Bret said in 1999. “Whenever we did a film with him, it would go round the girls’ grapevine: ‘He’ll make passes at you.’ He couldn’t resist trying to make it with all his leading ladies,” said Phyllis Calvert, Formby’s co-star in the 1940 film Let George Do It.

Florence Desmond, who was Formby’s leading lady in the mid-1930’s films No Limit and Keep Your Seats, Please, even branded Formby “a dirty little man” and a “dirty little Northern would-be Casanova”. George Melly was a fan of Formby – he chose his song Auntie Maggie’s Remedy as one of his Desert Island Discs choices – and the jazz singer was told by a friend of his actress sister Andrée that it was common knowledge on the northern theatre circuit that Formby would try to seduce dance girls by saying “‘Eee, I’m crazy about you” before offering them, with a wink, the chance to “play with my ukulele”.

Sarah Gregory, star of Zip Goes a Million, said Formby used inappropriate physical contact during filming. Formby’s behaviour would have attracted #MeToo publicity in the modern era, but at the time actresses could not risk exposing such a powerful star. The 21-year-old Googie Withers, 14 years younger than Formby when they made Trouble Brewing in 1939, recalled years later that Formby took advantage of a scene in which they fell into a vat of beer to touch her up. “Because we were in water, my skirt had ridden up.

He had his hand on my bare thigh and he kept it there and started to kiss me… Beryl was in on it like a flash screaming ‘cut, cut!’” It seems that many of Formby’s female co-stars were obliged to be part of the weird psychodrama of the Formby marriage. Formby’s sexual harassment usually occurred as part of a game of evading the hawk eye of Beryl.

Perhaps the strangest of all Formby’s adulterous liaisons was with a chanteuse who went by the stage name of Yana, an affair that began in June 1960, when Formby was top-of-the-bill in a revue at the Queen’s Theatre in Blackpool. Formby was 56 and Yana was 29 at the time.

Although Yana’s name hinted at an exotic background, the singer was in fact called Pamela Guard, a former hairdresser’s assistant from Billericay in Essex. She was famous enough to merit inclusion in the 1998 Daily Telegraph Third Book of Obituaries: Entertainers, which described her as “blatantly lesbian”. Formby, it seems, was unaware of her bisexuality, even though she was also living with an American actress at the time.

Their affair, which came when Beryl’s alcoholism had started spiralling out of control as she battled leukaemia, was apparently torrid. It prompted a memorably lurid exchange in Bret’s stage play Our George: The George Formby Story: A Play in 2 Acts, during a scene in which Yana is helping Formby get out of his Mr Wu Chinese costume, after one of their shows in Blackpool. “George, would you like to stick it between my t__s again?” Brett has Yana ask Formby. It’s a far cry from Formby’s innocent movie naïveté displays.

Bret, who has written biographies of Joan Crawford, Maurice Chevalier and Morrissey, also angered Formby fans with other revelations. Before he became a writer, Bret worked as an NHS administrator in Yorkshire, where he gained access to Formby’s medical records. Among the information he divulged in the book was highly personal detail about the singer’s time in a psychiatric hospital in York, where he was treated for depression and “morphine addiction”.

Another controversy in the book concerned the time in 1944 Formby was supposedly investigated by the Home Office’s Dance Music Policy Committee over sympathies to Hitler, a period Formby referred to as “a nightmare”. There were claims that his song Swim Little Fish supposedly mocked the effort against the German U-boats, which were at the time sinking British convoys in the Atlantic. The investigation was rumoured to have been instigated by a jealous actor. In any case, the pro-Hitler charge seems ludicrously far-fetched.

Formby was held in high regard by the government and his devotion to the war effort seems clear. He worked as a dispatch rider for the Home Guard and went on numerous overseas tours to entertain British troops, always reminding them that “it’s wonderful to be British”. In addition, the dream sequence in his movie Let George Do It, in which he descends from a balloon in the middle of a Nazi rally to punch Adolf Hitler in the face, was judged in a survey from The Mass Observation Project to have been “the biggest morale-booster of the Second World War.”

It’s highly likely that Formby would not have been able to explain himself adroitly in a nuanced argument about lyrics. He was deeply self-conscious about having left school at the age of seven and never having learned to read or write properly. His lack of intellect was sometimes cruelly mocked by his fellow actors. Desmond said of Formby that “the man’s as thick as two very short planks”, while actress Pat Kirkwood, described him as “a cretinous little creature”, adding that “if you tried to converse with him, you’d find there was no one at home”.

Although Formby had his detractors, he also had his high-profile fans. And none more elevated than Queen Elizabeth. The Queen’s parents were both Formby fans. He sang before King George VI at the 1937 Royal Variety Performance, and the king sent him a letter saying his family had been “convulsed with laughter” at Formby’s 1938 film It’s in the Air. He was later invited to give a private show at Windsor, which was watched by the young future monarch and her sister Princess Margaret.

In 2003, for his book about the Queen, Gyles Brandreth interviewed Deborah Bean, Her Majesty’s long-serving Correspondence Secretary. “During our conversation Mrs Bean revealed to me that the Queen had once told her that she loved the songs of George Formby, knew all of them, could sing them – and frequently did.” There were even reports that she once asked to be president of the George Formby Appreciation Society, although no corroboration of this exists.

In 2018, at a special Royal Albert Hall concert to celebrate the Queen’s 92nd birthday, the monarch was particularly delighted when Skinner, Harry Hill and Ed Balls joined members of The George Formby Society to deliver a version of When I’m Cleaning Windows, the Peeping Tom-style song about a man who spies on women undressing. The song was once banned as “not fit to be broadcast” by BBC chairman Lord Reith, who dismissed it as “a disgusting little ditty”.

A lot of Formby’s songs were innuendo-filled, including You Can't Keep a Growing Lad Down, With My Little Ukulele in My Hand and With My Little Stick of Blackpool Rock, which was also banned by the BBC for its smutty double-entendres. My Little Snapshot Album contained risqué lines for 1938: "And I’ve got a picture of a nudist camp, in my little snapshot album/ All very jolly but a trifle damp, in my little snapshot album/ There’s Uncle Dick without a care, discarding all his underwear/ But his watch and chain still dangle there, in my little snapshot album".

Formby was a witty songwriter – Our Sergeant Major is a fine example of war-time satire – and he attracted other influential fans too, including comedian Peter Sellers, who could do an uncanny impression of the Lancashire singer. Sellers praised Formby as “a terrific performer” and the ukulele man’s songs have been performed by Bill Haley, Richard Thompson and Lonnie Donegan.

John Lennon was also a fan – paying tribute by including Formby’s iconic line “it’s turned out nice again” in his song Free as A Bird – while fellow Beatle George Harrison was such a devotee that he bought the gold-plated banjolele ukulele that Formby used in live performances.

Beryl is often the butt of a story that claimed she limited Formby to a weekly allowance of five-shillings of pocket money in their early days, but once he made it big, he spent a fortune on cars and houses. Formby bought more than a hundred luxury cars in his most successful years, including 26 Rolls-Royces with personalised number plates.

Then there were the properties. In the early 1950s, Formby bought a lavish 24-room mansion at Foxrock, outside Dublin, telling a reporter who spotted him in the estate agent office that “I’m sick to death of the taxman robbing me of 90 per cent of my earnings.”

Some of his fortune came from lucrative foreign tours, including an eventful one in 1946 to South Africa, when he played to black audiences, despite angry complaints from Daniël François Malan, head of the National Party and the future prime minister who was one of the chief architects of apartheid two years later. When Beryl kissed a young black girl who presented Formby with a box of chocolates, Malan sought the couple out to shout at them. “Why don’t you piss off, you horrible little man?” replied Beryl. They were ordered out of the country, never to return.

By the late 1950s, life was becoming more difficult for the couple, despite the opulence of their home in Fairhaven, Lytham, which was originally called Cintra, but which Formby’s wife immediately renamed as ‘Beryldene’. Formby was closer to his dog Willie Waterbucket than he was to wife. Although Formby had been warned to take it easy after his heart attack in 1949, he was still smoking 40 Capstan Full Strength and Woodbine cigarettes a day – cheerfully calling them his “coffin nails” – and eating lots of beef-dripping toast. As Beryl’s cancer worsened she sought solace in drinking, sometimes consuming a bottle of whisky a day. She was 59 when she died on Christmas Day 1960.

Beryl’s illness had allowed him free access to conduct the affair with Yana, but when that ended – and with work now intermittent – Formby turned his attention to a local woman called Pat Howson. Formby was a friend of her father Fred (who as general manager of Loxhams Car Showroom in Preston had sold him cars) and Formby sometimes took the Howson family on holiday on his boat on the Norfolk broads. Pat Howson, then 35, taught religious education and was sympathetic when Formby told her that Beryl, an atheist, “tried to turn me away from my Catholic religion”.

In February 1961, they announced their engagement. “I first met her when she was nine, just a pretty little schoolgirl in ringlets,” 56-year-old Formby told The Daily Mirror. He said they reunited after his wife’s death and after a fortnight of courting he “popped the question”.

Just two days before the wedding, on March 6 1961, Formby died of heart failure. The aftermath of his death was engulfed in rancour. Formby’s mother Eliza vetoed Howson’s funeral arrangements and had her son buried in Warrington instead of Preston.

Although Formby left almost all his £2.2 million estate to Howson, his 82-year-old mother took the matter to court, reportedly saying her family would “fight that little floozy schoolma’am with their last breath”.

The legal battle lasted nearly a decade before a compromise was reached. The money seemed cursed, however. Howson died of ovarian cancer in 1971, aged just 46. Eliza lived on until 1981, when she died at 102.

The 150,000 fans who lined the 20-mile route of Formby’s funeral procession knew little of the truth about Formby’s life. They simply loved one of their own, a man who admitted that, “I’m just a clown without the make-up, the circus clown who magnifies the reactions of ordinary people to the things that happen around them.”