Of course Gen Z boys believe feminism is harmful – they’ve learnt it from the internet

So much for the open-mindedness of youth. A new survey, published today, found that boys and men from Generation Z are more likely than older baby boomers to believe that feminism has done more harm than good. I’m a member of Gen Z – and I’m not surprised. Why? Almost everything I first learnt about feminism was from social media.

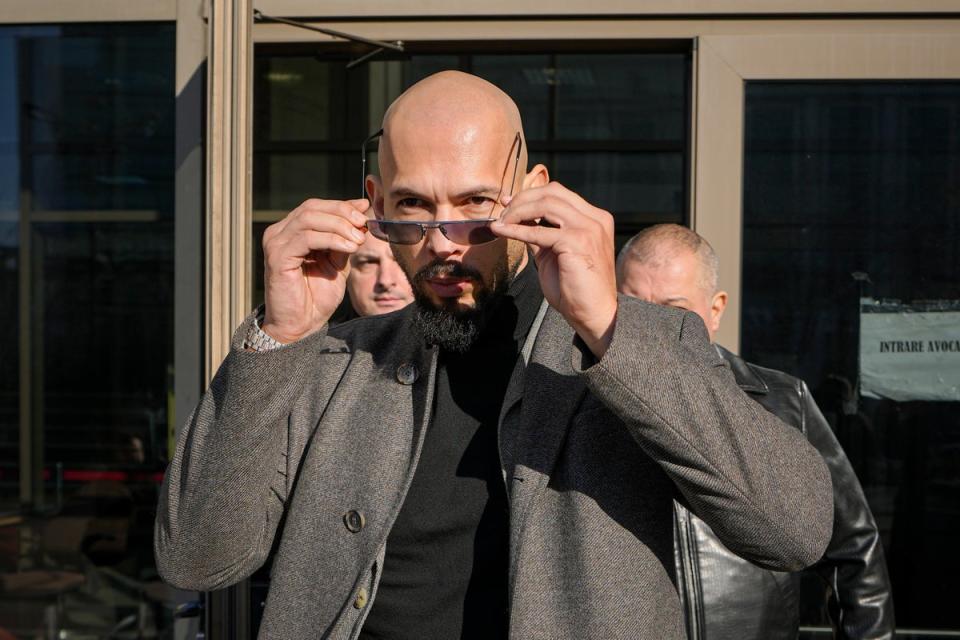

The survey in question, conducted by The Policy Institute at King’s College London and the Global Institute for Women’s Leadership, polled 3,600 UK males aged between 16 and 29. It found that one in four men polled stated that it is harder to be a man than a woman, while – even more distressingly – a fifth of respondents now look at social media influencer Andrew Tate favourably. Tate, a self-proclaimed “success coach” and “pick-up artist”, has made a living schooling young men and boys on how to charm, cajole, coerce or harass women into sleeping with them. Currently facing charges in Romania of human trafficking and rape (all of which he denies), Tate has become the poster boy for toxic masculinity. His popularity (amounting to 8 million Twitter/X followers) among Gen Z speaks to a troubling step backwards for many of my peers. When it comes to the corrosive spread of online misogyny, however, Tate is a symptom – not the cause.

If we look at this apparent regression by the younger generation, it seems almost too easy to point fingers at the internet. But I’m someone who has grown up online; I made my first Facebook account aged eight. I have seen first-hand how much my generation relies on influencers and social media stars for information. Being a woman, I’m not in Tate’s target demographic. But if I were, I would have likely been subjected to the marketing machinery used to lure others into his orbit.

Of course, the internet is no excuse for misogyny: the men who are absorbing the noxious content must also be held accountable. But whether you’re asking for it or not, pretty much all of your online activity is dependent on what your algorithm is showing you. My algorithm has given me the “feminism is good and great” strain, offering up aesthetically pleasing pink-coloured infographics with messages like “Less catcalls, more cats”. Feminism has been packaged to me in a way that was palatable and hard to disagree with. But I know that my male Gen Z peers see something entirely different. Algorithms often operate on extremes: because people tend to click on and engage with the most sensational, hyperbolic content, this is what the algorithm serves up. A social media algorithm isn’t necessarily evil – just amoral, and ripe for exploitation by the most extreme and predatory content-pushers.

Professor Bobby Duffy, director of the policy institute at King’s College London that authored the previously mentioned poll, told The Guardian that they are seeing an “unusual” generational pattern when it comes to Gen Z’s opinions on feminism. Typically, younger generations are consistently more comfortable with emerging social norms, though the survey suggests that, with my peers, the opposite may be happening. “This points to a real risk of fractious division among this coming generation,” said Duffy.

Could these “fractious divisions” be explained by the prevailing ideas about masculinity and misogyny on the internet? It certainly feels like it. On YouTube, in particular, the concept of masculinity that’s being espoused by the likes of Tate and Canadian author Jordan Peterson – as well as, to a different degree, figures such as British YouTuber-boxer KSI, with his 24 million subscribers – needs to be challenged. It is an image rooted in patriarchy and gender inequality, a paradox wherein men are simultaneously the dominant sex, entitled to power and influence over women – while also being the victims of so-called unruly and oppressive feminists. The Financial Times’ Henry Mance wrote that Tate’s messaging “has resonated with some boys, perhaps in particular those who felt that society has frowned on masculinity, and by extension, themselves”.

There is also, unfortunately, no easy solution to all this. Social media’s algorithmic sprawl is like the ocean – vast and churning and impossible to fight. Platforms like Twitter/X or TikTok need to do a better job at suppressing harmful and misogynist content. Or if this fails, changes in legislation may be an avenue for improvement.

On an individual level, perhaps the biggest difference we can make is actually talking to the young boys and men in our lives. Maybe the reason Tate and co have such sway with Gen Z is because they’re one of the few people really trying to connect with them. We need to talk to them too – otherwise, it seems they’ll just continue to hear the echo of their own voices.