Oxford research claiming two-thirds of Britons may have overcome coronavirus 'has key failings', experts warn

Health experts have questioned Oxford University research that suggests more than two-thirds of the UK may have already been infected with the coronavirus.

An Oxford team put together a “susceptible-infected-recovered” model based on the number of coronavirus-related deaths in the UK and Italy.

Numerous assumptions were made, including the number of people a patient goes on to infect, the likelihood of death among vulnerable individuals, and the time between catching the infection and dying.

According to the scientists’ stimulations, up to 68% of Britons may have caught the coronavirus by 19 March.

This may be a welcome thought for many, suggesting the prospect of herd immunity.

Latest coronavirus news, updates and advice

Live: Follow all the latest updates from the UK and around the world

Fact-checker: The number of COVID-19 cases in your local area

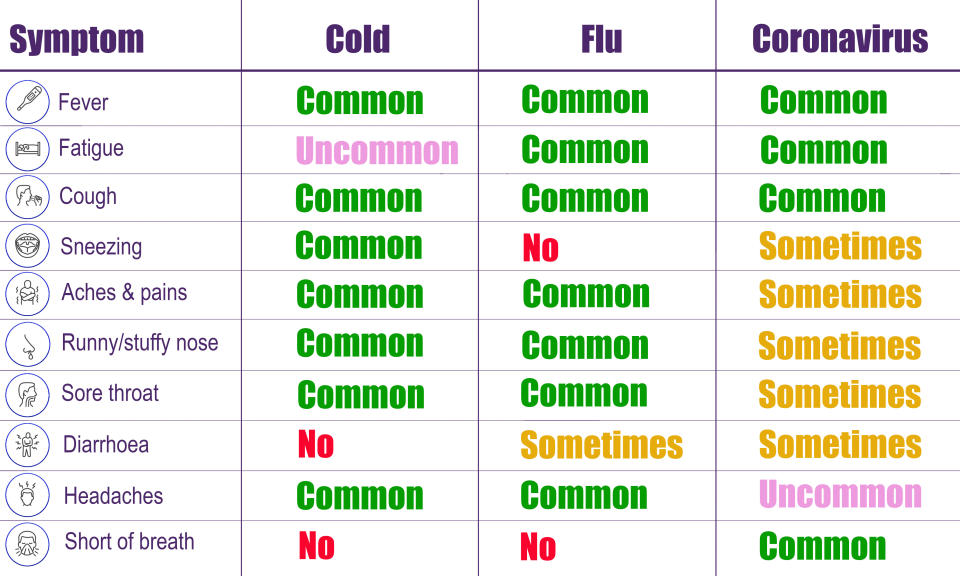

Explained: Symptoms, latest advice and how it compares to the flu

With draconian measures forcing all Britons to stay more or less inside, knowing you have overcome the virus and are unlikely to catch it again may allow people to go back to their normal routine.

Experts have warned, however, that the research “suffers from a number of key failings” and is “open to gross over-interpretation”.

The new coronavirus is thought to have emerged at a seafood and live animal market in the Chinese city Wuhan, capital of Hubei province, at the end of last year.

Since the outbreak was identified, more than 436,100 cases have been confirmed worldwide, of whom over 111,800 have “recovered” to date, according to John Hopkins University.

Globally, the death toll has exceeded 19,600.

Cases have been plateauing in China since the end of February, with Europe now the epicentre of the pandemic.

The UK has had more than 8,100 confirmed cases and 427 deaths.

Research ‘should not be given much credibility’

The Oxford research is yet to be peer reviewed, with the scientists behind it releasing a draft copy of their findings.

Peer-reviewing involves a panel of independent experts weighing in on a study, highlighting its strengths and weaknesses.

Many worry the research is based on too many assumptions.

“The work models one of the most important questions, how far has the infection really spread, in the total absence of any direct data,” said Professor James Wood from the University of Cambridge.

“The authors acknowledge their results are very sensitive to the assumptions they have made, but still draw conclusions from the model fit.

Read more: Coronavirus: is it safe to go to the supermarket?

“[The results] substantially over-speculate and [are] open to gross over-interpretation by others”.

Professor Paul Hunter from the University of East Anglia agreed, adding the research “suffers from a number of key failings which make me doubt its utility”.

His “main criticism” is the model assumes “complete mixing of the population”.

“We do not all have an equal random chance of meeting every other person in the UK, infected or otherwise,” said Professor Hunter.

The Oxford scientists made assumptions about the coronavirus’s basic reproduction number, which has been debated in the past.

The basic reproduction number is the number of people a patient statistically goes on to infect.

For example, a number of three means every patient is expected to pass the virus to three others.

This is tricky to calculate, with Professor David Heymann – from the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine – previously telling Yahoo UK that basic reproduction numbers “change daily as new information comes in”.

Read more: How lockdown may be affecting children's mental health – and how parents can help

“As far as I can tell, the [Oxford] model also assumes all those infected, whether they are asymptomatic, mildly ill or severely ill are equally infectious to others,” said Professor Hunter.

“This is almost certainly false.”

The coronavirus mainly spreads face-to-face via infected droplets that have been coughed or sneezed out.

There is also evidence it may be transmitted in faeces and urine, with some patients reporting diarrhoea.

If a patient is asymptomatic – and therefore not sneezing, coughing or having diarrhoea – they would not be expected to pass the virus on as readily.

Professor Hunter concluded the research “should not be given much credibility and should certainly not influence choice of strategies” when it comes to combating the outbreak.

Others were similarly dubious of the assumptions made.

“This is interesting work, but is hampered by the same issues that impacts all epidemiological models,” said Professor Jonathan Ball from the University of Nottingham.

“They rely on assumptions that at the moment are based on only a paucity of scientific fact about how this virus transmits.”

Professor Mark Woolhouse from University of Edinburgh called the results a “hypothesis rather than fact”.

“If correct this would have huge implications,” he said.

“It would imply the main reason why [the coronavirus] epidemics peak is the build-up of herd immunity.

“Though that would not change current policy in the UK, which is focused [on] reducing the short-term impact of the epidemic on the NHS, it would change enormously our long-term expectations, making a second wave significantly less likely and raising the possibility the public health threat of [the coronavirus] will diminish all around the world in the coming months.”

One expert, however, welcomed the new research.

“This theoretical simulation rests on a key assumption which may be or may not be correct,” said Professor James Naismith from the University of Oxford, who was not involved in the study.

“The work is a contribution to the scientific debate and science often advances by challenges to what seems perceived wisdom.”

All agreed with the Oxford scientists’ call to make testing more widespread.

“We desperately need to know what proportion of the population have been infected and have not become ill, and whether those people develop immunity, and if they do not become ill, whether they pose a risk of infection to others,” said Professor Hunter.

Health secretary Matt Hancock announced on Tuesday evening the UK has bought 3.5 million antibody tests.

Antibodies are proteins released by the immune system to fight off an invading pathogen, like a virus.

Once the infection has passed, “memory” antibodies are produced that act quickly if they spot a virus they have encountered before.

Detecting these antibodies would suggest an individual has fought off the virus, has immunity and is free to go back to normal life.

What is the coronavirus?

The new coronavirus is one of seven strains of a class of viruses that are known to infect humans.

Others include the common cold and severe acute respiratory syndrome (Sars), which killed 774 people during its 2002/3 outbreak.

Early research suggests four out of five cases are mild.

In severe incidences, pneumonia can come about if the infection spreads to the air sacs in the lungs, causing them to become inflamed and filled with fluid or pus.

The lungs then struggle to draw in air, resulting in reduced oxygen in the bloodstream and a build-up of carbon dioxide.

The coronavirus has no “set” treatment, with most patients’ immune systems fighting off the virus naturally.

In severe cases, hospitalisation may be required if a patient needs “supportive care”.

This may include ventilation while their immune system gets to work.

Hand-washing and social distancing are thought to be the best ways to ward off infection.