Coronavirus: the nine most important questions being asked by scientists

Scientists have put together what they deem to be the nine most important questions on the coronavirus.

Virtually unheard of at the start of the year, the new strain has spread well beyond the Chinese city of Wuhan, where the virus is thought to have emerged at a seafood and live animal market at the end of last year.

Since the outbreak was identified, more than 387,800 cases have been confirmed across more than 160 countries, according to Johns Hopkins University.

Early research suggests four out of five cases are mild, with more than 101,900 patients “recovering” to date.

Latest coronavirus news, updates and advice

Live: Follow all the latest updates from the UK and around the world

Fact-checker: The number of COVID-19 cases in your local area

Explained: Symptoms, latest advice and how it compares to the flu

With the World Health Organization (WHO) declaring the outbreak a “global emergency” and later referring to it as a pandemic, many are anxious how the infection may play out.

Scientists from The University of Hong Kong looked at the evidence available to “highlight the most important research questions in the field from their personal perspectives”.

1. Coronavirus: what is the situation in Wuhan?

Cases in China have been plateauing since the end of February, with Europe now the epicentre of the pandemic.

Hubei province, of which Wuhan is capital, has been on “lockdown” since the beginning of the year.

Travel restrictions in Hubei, excluding Wuhan, will be lifted at midnight. The lockdown in Wuhan will be partially lifted on 8 April.

“The easing of lockdown restrictions in Hubei and soon in Wuhan offer hope for much of the rest of the world that an end to the stringent control measures can be in sight,” said Professor Andrew Tatem, from the University of Southampton.

The lockdown helped protect other Chinese cities, although cases in Wuhan continued to rise initially.

Based on the number of “exported” patients from Wuhan to outside mainland China, more than 70,000 people are thought to have been infected in Hubei’s capital on 25 January.

To determine whether this is an underestimate, the scientists want to see RNA and antibody tests carried out within “several representative residential areas”.

The coronavirus is an RNA virus. Put simply, RNA is a precursor to DNA.

Antibodies are proteins released by the immune system to fight an invading pathogen.

Once the infection has passed, a new type of antibody is produced that “remembers” the infection if it strikes again.

Carrying out these tests would enable scientists to predict the true number of patients, as well as how many did not develop the tell-tale fever and cough.

The rate of asymptomatic infections has been debated, with these patients still able to pass the virus on.

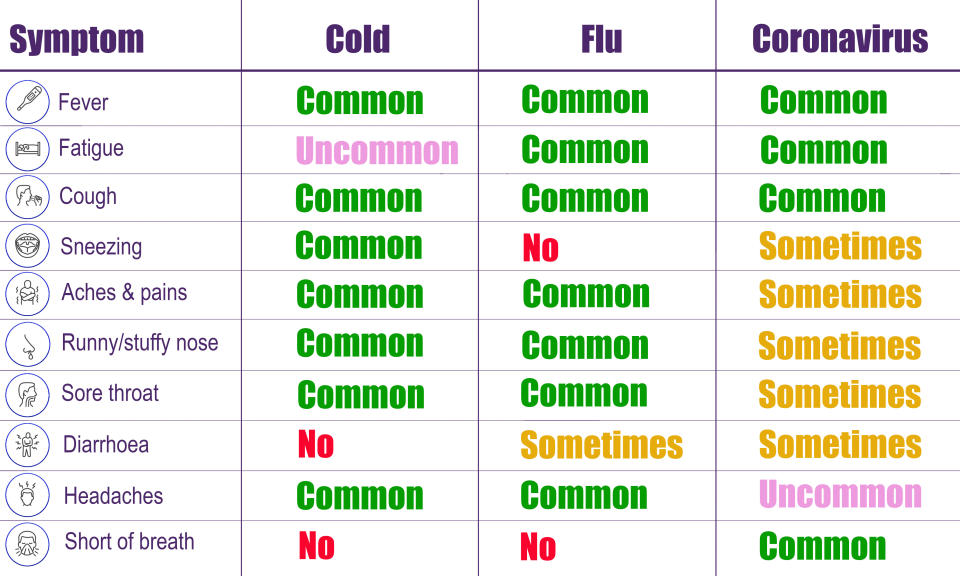

The scientists also want patients tested for flu, which peaked in January in Wuhan and causes some of the same symptoms.

“It will be of interest to see whether the flu season had ended and how many people having a fever now are actually infected with influenza virus,” they added.

2. How infectious and dangerous is the coronavirus?

The virus is thought to have “jumped” from an animal into a human.

Officials confirmed early on the virus can spread between people – mainly face-to-face via infected droplets that have been coughed or sneezed out by a patient.

There is also evidence the virus may be transmitted in faeces and urine and can survive on surfaces.

How contagious the coronavirus is has been up for debate.

All infectious pathogens have a “basic reproduction number”, which is the number of people a patient statistically goes onto infect.

For example, a number of three means every patient is expected to pass the virus to three others.

In mid-February, scientists from the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine estimated the coronavirus’ basic reproduction number fluctuated between 1.5 and 4.5 before travel restrictions were introduced in Wuhan, stressing “substantial uncertainty”.

This led them to predict the outbreak may peak in China in “mid-to-late February”.

Speaking at the time, Dr Robin Thompson, from the University of Oxford, said: “One proviso must be forecasting the peak of any outbreak is challenging, and so there is significant uncertainty in estimates of both the timing of the peak and the total number of cases that will occur.”

Professor David Heymann, from the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, previously told Yahoo UK basic reproduction numbers “change daily as new information comes in”.

“Determining the real basic reproduction number will shed light on whether and to what extent infection control measures are effective,” the Hong Kong scientists wrote in the journal Cell & Bioscience.

When it comes to how dangerous the coronavirus is, the vast majority of patients worldwide are expected to make a complete recovery without any hospital care.

Deaths are largely occurring in the elderly or otherwise ill, with the toll exceeding 16,700.

While the WHO previously estimated a death rate of 3.4%, a more recent analysis predicted 1.4% may be more accurate.

Nevertheless, the organisation has declared the outbreak a “global emergency”, the highest alarm it can sound.

The Hong Kong scientists want to know whether the virus will become less contagious the more people it infects or if transmission will sustain, raising the risk it will be a seasonal issue.

3. How many people do asymptomatic patients infect?

On 3 March, the WHO’s director-general Dr Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus said: “Evidence from China is only 1% of reported cases do not have symptoms”.

Many experts peg the true number to be considerably higher.

The Hong Kong scientists claimed 12.1% of patients do not develop a fever.

Fellow coronavirus severe acute respiratory syndrome (Sars) failed to raise a patient’s temperature in just 1% of cases, they added.

Sars was brought under control in around eight months, with no reported cases since 2004.

The Hong Kong scientists worry patients not showing symptoms may be “difficult to identify and quarantine”.

Temperature scanners at airports and even the entrance to shops in Wuhan may therefore have limited effectiveness, they added.

“However, based on previous studies of influenza viruses and community-acquired human coronaviruses, the viral loads in asymptomatic carriers are relatively low,” said the scientists.

If patients are not actively sneezing and coughing, it is harder for the virus to infect new people.

4. How many patients could become infected via faeces?

The WHO-China Joint Mission on Coronavirus Disease 2019 noted “viral shedding” has occurred in human waste.

Fears arose when two people living 10 floors apart in the same Hong Kong apartment block were diagnosed in mid-February.

Officials later found an unsealed pipe in one of the patient’s bathroom, which could have allowed the virus into her apartment.

With Sars, the WHO confirmed “inadequate plumbing” was a “likely contributor” to the spread in “residential buildings in Hong Kong”.

Diarrhoea has been reported with the new coronavirus, but to a lesser extent than Sars, suggesting the faecal-oral route is responsible for fewer cases.

“The possibility of transmission via sewage, waste, contaminated water, air condition system and aerosols cannot be underestimated”, said the scientists, calling for more studies.

5. How is the coronavirus diagnosed?

Polymerase chain reaction tests were the only method of diagnosis at the start of the outbreak.

This finds small amounts of RNA in a respiratory sample.

Using a process known as amplification, the RNA is copied until there is enough for analysis.

In mid-February, doctors in Hubei started classing people as “definitely infected” if they presented with symptoms, alongside a CT scan showing a chest infection.

This gave the impression cases had spiked overnight, despite one expert stressing it was “solely an administrative issue”.

The Hong Kong scientists claimed the change to diagnosis enabled suspected patients to be “identified and quarantined as early as possible”.

More recently, antibody tests have become available.

The scientists stressed there is an “urgent need” for antigen tests to help identify people who are actively infectious.

Antigens are proteins on pathogens that bring about an immune response.

6. How is the coronavirus treated?

The coronavirus is “self-limiting” in more than 80% of patients, with their immune system naturally fighting the virus off.

Severe pneumonia occurs in around 15% of cases, based on existing data.

These patients are given supportive care, like ventilation, while their immune system gets to work.

The coronavirus has no set treatment or vaccine, however, several jabs are under development.

A UK trial is looking at whether the malaria-drug chloroquine reduces the number of symptomatic infections.

US president Donald Trump wrongly claimed the medication has been approved for the coronavirus, when it is in fact only available in the US for “compassionate use”, if a patient is in a life-threatening condition.

The BBC reported the drug “seems to block the coronavirus in lab studies”, however, there are no complete trials proving its effectiveness in patients.

The anti-Ebola drug remdesivir was found to be effective against fellow coronavirus Middle East respiratory syndrome (Mers) in monkeys, giving hope it may also work now.

Mers killed 858 people during its 2012 outbreak, with a handful of cases arising every year.

Disappointingly, an HIV drug was not found to speed up “the time to clinical improvement” with the current coronavirus.

Doctors in China are said to be giving steroids to drive down inflammation and prevent lung tissue scarring.

“The window in which steroids might be beneficial to patients is very narrow”, said the Hong Kong scientists.

“In other words, steroids can only be used when the [coronavirus] has already been eliminated by human immune response.”

Given too soon, the drug may boost virus replication, worsening symptoms and transmission, they added.

7. Will a vaccine become available for the coronavirus?

Creating a vaccine could lead to herd immunity, preventing the coronavirus taking hold if it re-emerges.

Experts have repeatedly stressed a jab will not be available for this ongoing outbreak.

If the coronavirus becomes seasonal, “vaccine development becomes necessary for prevention and ultimate eradication”.

8. What animal did the coronavirus come from?

Like Sars and Mers, research suggests the coronavirus started in bats.

A strain found in the bat species Rhinolophus affinis “shares 96.2%” of its DNA with the coronavirus.

The bat strain, however, does not target the same receptor to gain entry into cells.

Some scientists believe the scaly anteater pangolins may be the “intermediate host”.

A strain that affects pangolins “shares about 90%” of its DNA with the coronavirus and carries a “receptor-binding domain” that may enable it entry into cells.

Most of those who initially became unwell worked at, or visited, the Wuhan market.

The market sold a range of alive and dead animals, including poultry, donkeys and hedgehogs.

“The jury is still out as to what animals might serve as reservoir and intermediate hosts of [the coronavirus],” said the Hong Kong scientists.

“Although [the] market was suggested as the original source of [the coronavirus], there is evidence for the involvement of other wild animal markets in Wuhan.

“In addition, the possibility for a human ‘superspreader’ in the market has not been excluded”.

9. Why is the coronavirus killing relatively fewer patients than Sars?

The coronavirus has killed considerably more patients than Sars, however, it has also infected more people.

Sars is therefore thought to have a higher death rate, the percentage of patients that die out of the number of cases.

Of all the strains of the coronavirus class, the circulating one is said to be most genetically similar to Sars.

In February, scientists from Fudan University in Shanghai found it appears to be 89.1% genetically similar to “a group of Sars-like coronaviruses”.

Sars is said to have been “exceedingly potent” at suppressing the immune system and activating dangerous inflammation.

The new coronavirus is not thought to act in the same way, with the scientists calling for the two strains’ modes of action to be compared.