Consent, Dorfman, National Theatre, London, review: One of Nina Raine's most enjoyable and intelligent plays yet

The two champagne-flute-chiming couples at the centre of Nina Raione’s new play Consent are high-flying lawyers who would be happier trying to converse in one of the African clicking languages than doff their mock-jaded irony around even the most basic human watersheds, such as wetting a new baby's head.

Only a highly intelligent author such as Raine can evoke the terrible insufficiency of intelligence alone – and of all the brainy smart talk that it generates – to save the souls of anyone. The men talk with a nasal insider-snidery that sounds like a blocking-out of good things: fresh air, for example.. And of course, sex as a subject runs like obligato under everything.

The easiest way to market this work would be to mischaracterise it as an issue play about the boiling blur with regard to proof and motivation in legal cases that turn on a charge of date- and marital-rape. And that would not be false, just inadequate. Heather Craney is excellent as Gayle, the working-class woman who alleges that she was raped on the day of her sister's funeral. The fact that she was already in therapy does not strengthen her case. But later she seeks out the lawyers and poops a private party in a tricky but adroitly handled scene not dissimilar to the irruptions into the court by mad Queen Margaret in Richard III.

The grotesque irony is that her credibility was questioned because she was receiving treatment for the long-term damage wrought by the experience of being violently assaulted as a teenager. The play is very alive to how the fine tines in the fork of jurisprudence (so to speak) – always a-quiver to be seen to be acting impersonally and impartially – may miss the heart of the matter, unlike, say, at at times, a well aimed kitchen knife...

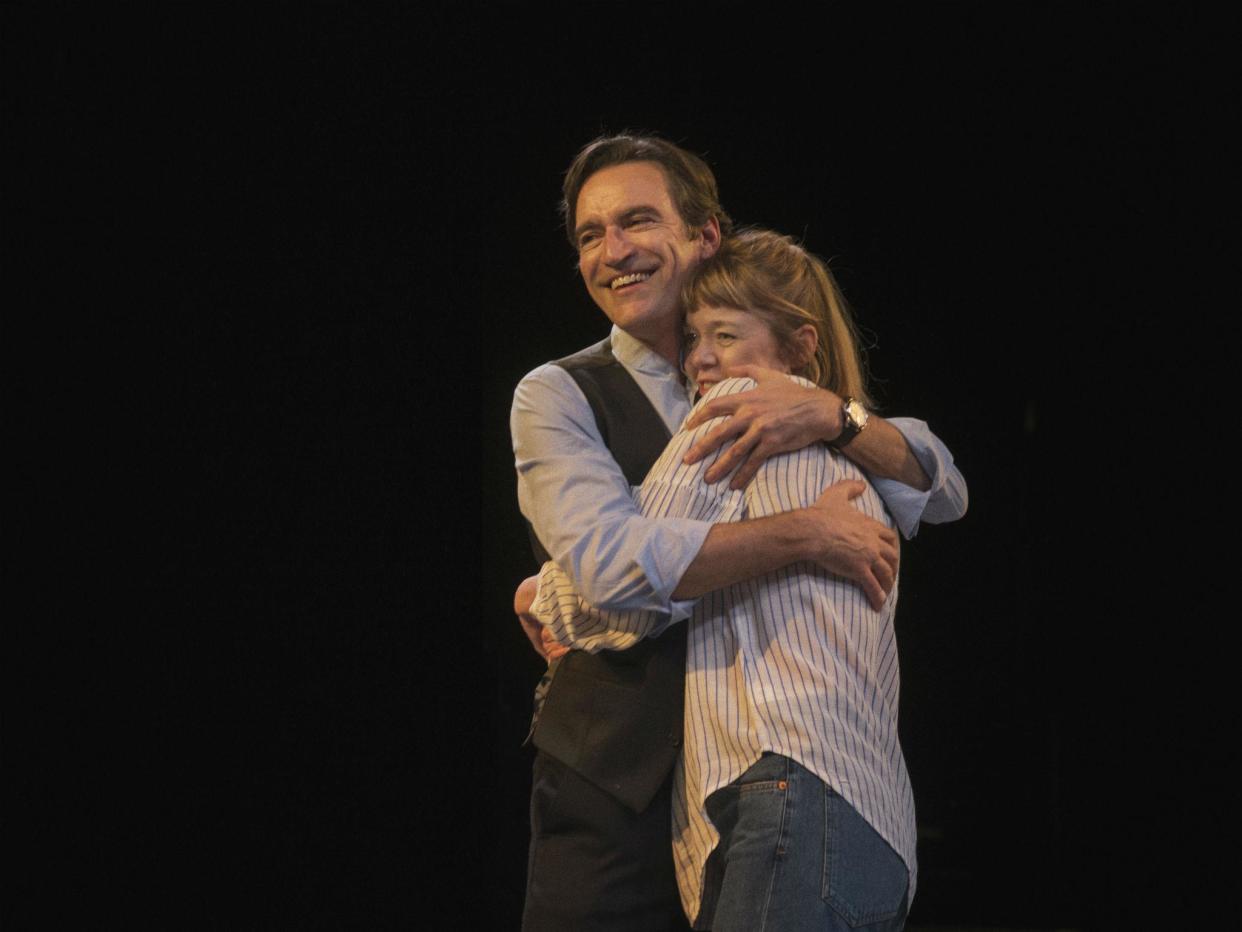

Directed by Roger Michell with a wonderfully light-footed nippiness as it darts around among the domestic landmines, the play ripples out to cover ordinary marital misery. Anna Maxwell Martin and Ben Chaplin are unimprovable as the kind of couple who have no statute of limitations on long-festering grudges. She thinks that only by subjecting him to infidelity – with Pip Carter's superb Tim – will she get her husband to realise the hurt he has caused her by his adulteries. She does not bargain for the law of unintended consequences.

They escalate into an orgy of frantic mutual recrimination about who was doing what to whom in the bout of sex they had just before she threw him out for good. She's driven even more demented that custody battles don't take marital assault into account because such brutality doesn't directly affect the interests of the child. After such knowledge, what forgiveness? And what does it mean to forgive in such circumstance. The final scene is unforgettable – like a weird reversal of the statue scene in The Winter's Tale – as she wavers tearfully toward her husband who is immobilised in a posture of compromised penitence. One of Nina Raine's most enjoyable and intelligent plays yet. Unreservedly recommended.