What the changing face of motherhood has taught us

In 2006, I gave birth to my first child. Things didn't go plan. They rarely do. After a 36-hour labour and an emergency Caesarean, I was wheeled, shellshocked, into a ward I barely remember, my giant 10lb baby in a transparent plastic tray by my side. I tried to breastfeed. She wouldn’t latch. And so began the first of many failures that have been chipping away at my confidence for 17 years, for motherhood is the best and hardest thing I’ve ever done.

Despite one of the most talked-about TV shows of the year being Honey, We’re Killing The Kids, a warts-and-all view of family life that would have proved an effective contraceptive for anyone harbouring doubts about whether to procreate, 2006 was a pretty good year to become a mother. Sure Start, the Labour government’s 1998 initiative to ‘give children the best possible start in life’ was accessible and well-funded, while Mumsnet, launched in 2000, gave new parents access to a cornucopia of advice via a platform that was mercifully focused on words and not pictures.

While I struggled with early motherhood and felt oddly dissociated at times, I was fortunate to escape postnatal depression. ‘Why am I not feeling joyful?’ I remember thinking as I wheeled my Bugaboo down a particularly grim stretch of road. Had I spent my time scrolling through Reels of new mums in oatmeal-coloured co-ords with washboard abs, the transition from autonomous human to 24/7 caregiver would have been exponentially harder.

Instagram launched in 2010, the same year my second daughter was born, but by the time it had taken off, I was well past the point where every glowing depiction of motherhood felt like a personal failure. But long before social media existed, motherhood was being oversold – so much so that in the 1950s, it was touted as a woman’s sole purpose. The questionable construct of the 1950s housewife was an attempt to rebrand domestic life after women took on men’s jobs during the Second World War, enticing us back to the kitchen where we belonged and leaving the menfolk to enjoy their money and freedom.

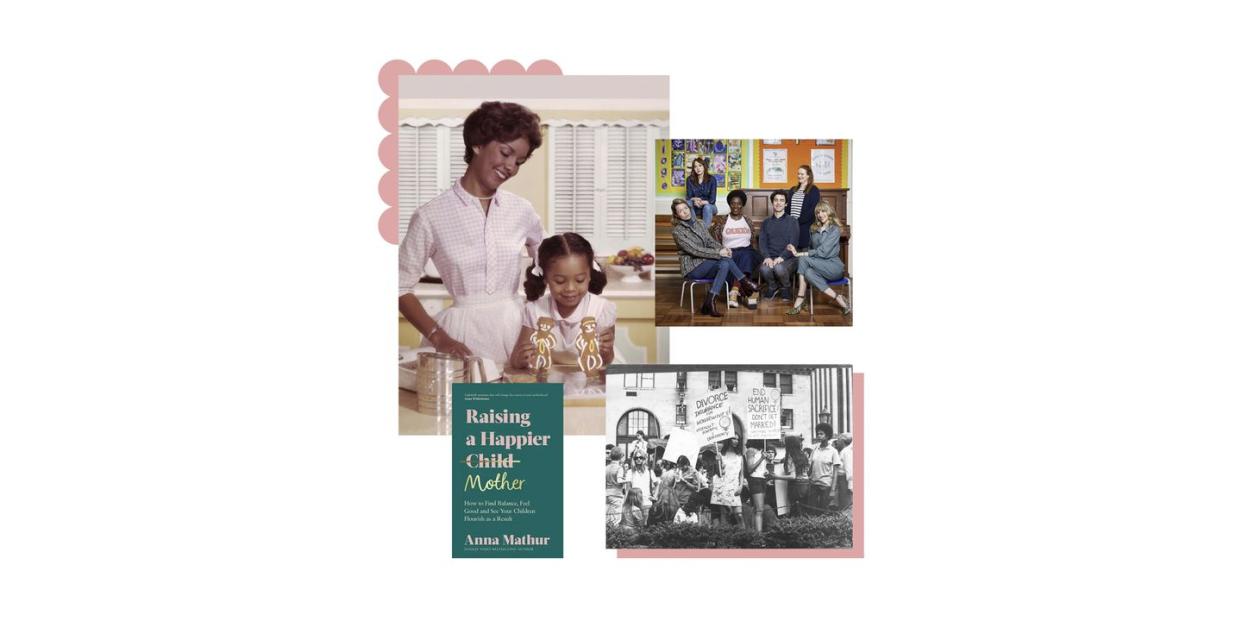

In the 1960s and 1970s, the women’s liberation movement attempted to challenge these prevailing notions of female domesticity, believing – quite rightly – that the dominant model of man as breadwinner and woman as homemaker was a source of women’s oppression. There was also a backlash against Mother’s Day, which many believed reinforced the problem. If motherhood is so satisfying, they argued, why not let men have a turn? The women’s lib movement also highlighted the invisibility of domestic labour – these days usually referred to as ‘unpaid emotional labour’ – and urged society to share the burdens of motherhood so that women could explore their identities beyond the domestic sphere.

During the 1980s, Dolly Parton starred in the film (and sang the title song) 9 to 5 and Melanie Griffith had a huge hit with "Working Girl". Both explored the highs and lows of working life, but while more mothers were working, and in higher managerial positions, most felt hugely unsupported. When Helen Gurley Brown, then editor of US Cosmopolitan, wrote Having It All in 1982, little did she know how problematic the phrase would become, or how many women would have it weaponised against them. Gurley Brown’s self-help book was more focused on money, sex and appearance than anything as prosaic as childcare advice, but for a generation of working mothers desperate for a road map, it proved compelling.

We all need a map at some point in our lives, but nevermore so than when we’re pregnant, for in the pantheon of uncertainties, none is bigger or more daunting than impending motherhood. There are infinite ways to trace society’s fluctuating attitudes towards motherhood, but one particularly salient way is via parenting books. Every decade has its favourites. While my mother adhered to Dr Spock, my guru was Gina Ford, on the basis that everyone else revered her in 2006 (new mothers are nothing if not sheep). In truth, her rigid approach was too tough for me, though admittedly it worked, if you could bear to leave your baby crying. By the 2010s, science-based parenting books were more in vogue; more recently, these have given way to books that focus on mum’s welfare as well as baby’s, such as Anna Mathur’s bestselling Raising A Happier Mother (2023).

Now that my daughters are in their teens, I’d probably opine that the best way to ‘raise a happier mother’ is to trust your own instincts. The more books you read, the more conflicting advice you receive: you’re either too strict (Ford’s controlled crying), too soft (co-sleeping), too controlling (David McCullough’s snowplough parenting), too demanding (Amy Chua’s tiger mom) or too indulgent (Amy Krouse Rosenthal’s yes days). No wonder so many mothers feel they can never get it right.

But if the pressure to be the perfect parent is real, so is the pressure to pick a tribe. On the plus side, there are more to choose from than there used to be, many of which grant you permission to be imperfect. When the novelist Rachel Cusk published A Life’s Work in 2001, her searingly honest account of motherhood was anomalous at the time. Writing in the Guardian in 2008, Cusk recalled reading a review – written by a woman – which stated: ‘If everyone were to read this book, the propagation of the human race would virtually cease.’ She was also accused of everything from child-hating to selfishness to having postnatal depression.

When the journalist Molly Gunn launched her Selfish Mother blogzine in 2013, it was as a riposte to the idea that mothers should be selfless, and gave a platform for other mums to share their ups and downs. Today, there’s less pressure to be a perfect mummy or a yummy mummy, and every permission to be a slummy mummy or a scummy mummy instead. At precisely what point in history these less-than-saintly archetypes became aligned with gin I’m not sure, but it was around the same time that the ‘mumfluencer’ was birthed, clutching an Instagrammable G&T in her elegantly manicured hand.

This is where, for me, the cult of motherhood got a bit dark. If the selfish/slummy/scummy mummies were poking fun at themselves for their less-than-perfect parenting, too many of the mumfluencers were weaponising their shortcomings for followers and financial gain. Even if their intentions may have started out as honourable, many were soon corrupted by the lure of the freebies and brand sponsorships that came their way.

Competition between mumfluencers was heated and often toxic, as they vied for supremacy via a barrage of judiciously curated posts (and, later, Reels) that bore as tenuous a relationship to most women’s lived experience of motherhood as Demi Moore’s glossy 1991 Vanity Fair cover did to their experience of being pregnant. In the 1990s, everyone wanted to celebrate pregnancy as a life stage and aesthetic, but nobody had much interest in supporting women once they actually gave birth. Short of sharing discount codes for breast pumps and maternity wear, too many mumfluencers felt similarly disengaged. Having given birth at least a decade before mumfluencers became A Thing, I watched half impressed, half horrified as they commodified relatability with the laser focus of a Kardashian.

Relatability has always sold, and no one is more susceptible to its charms than a woman whose lifestyle, confidence and autonomy has been impacted by motherhood. It’s why TV shows depicting the real, authentic, warts-and-all version such as Catastrophe (2015), Motherland (2016) and Workin’ Moms (2017) are so deservedly successful. Interestingly, my teenage daughters love these shows as much as I do, watching them on repeat in a way that I hope better prepares them for their own journeys into motherhood, when the time comes and if they choose to go there. Or maybe Motherland’s Julia (played brilliantly by Anna Maxwell Martin) will put them off.

Motherhood has always been beset by good and bad role models, and in 2024 there are more platforms than ever from which to sell or seduce, encourage or intimidate, help or hinder. It seems to me that the best forces for good are also forces for positive, constructive change. I’m full of admiration for women such as Mother Pukka’s Anna Whitehouse, who has used her platform to help change the law about flexible working (thanks to her #flexappeal, a flexible working law is mooted to come into effect later this year). I’m also in awe of Joeli Brearley, whose Pregnant Then Screwed charity continues to do so much to highlight the motherhood penalty and to campaign for affordable childcare for all.

This campaigning is desperately needed: a 2023 survey by The Fawcett Society found that almost twice as many working mothers as fathers have considered leaving their jobs because of the burden of childcare, with mothers disproportionately feeling the strain of balancing childcare and work; 30% of those surveyed reported challenges in finding flexible working hours, while 34% felt their career progression had been hindered by childcare responsibilities. According to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), the UK is among the most expensive countries in the world for childcare, with the monthly cost of putting one child through nursery now exceeding mortgage repayments in many parts of the country. Average childcare fees for children under two, meanwhile, increased by 6.5% between 2022 and 2023, according to Government figures.

In terms of how motherhood is viewed today, we could wax lyrical about how there’s less pressure to ‘snap back’ to your pre-baby body, more acceptance of differing parenting styles and a chorus of diverse voices (Philippa Perry, Janet Lansbury, Emily Oster, Lucy Jones) who debate and encourage rather than lecture and demean. But while culturally there is more space for authentic conversations about motherhood, economically, mothers are appallingly unsupported. No mother should have to give up her career because she can’t afford childcare – a disgusting state of affairs that says everything about how little she is valued.

My elder child turns 18 this year. As anyone whose kids have turned 18 will tell you, this changes your perspective on motherhood almost overnight. However challenging you found it, it will be bathed in golden light, as you realise all the clichés are true and their childhood really is over in a heartbeat. ‘I’ve managed to keep them alive,’ you’ll breathe, incredulous as they order their first legal G&T. Your role will be different now: less hands-on, but still connected by invisible thread woven from unconditional love and memories. Childhood ends, but motherhood doesn’t. Nor would you want it to.

My best advice? Be kind. Don’t judge. All kids are hard to raise, but some are harder than others. There is no such thing as the perfect mum: we are all doing the best we can with the capacities we have available. And whatever your family circumstances, surround yourself with friends, because it really does take a village.

You Might Also Like