Do celebrity endorsements ever influence where we travel?

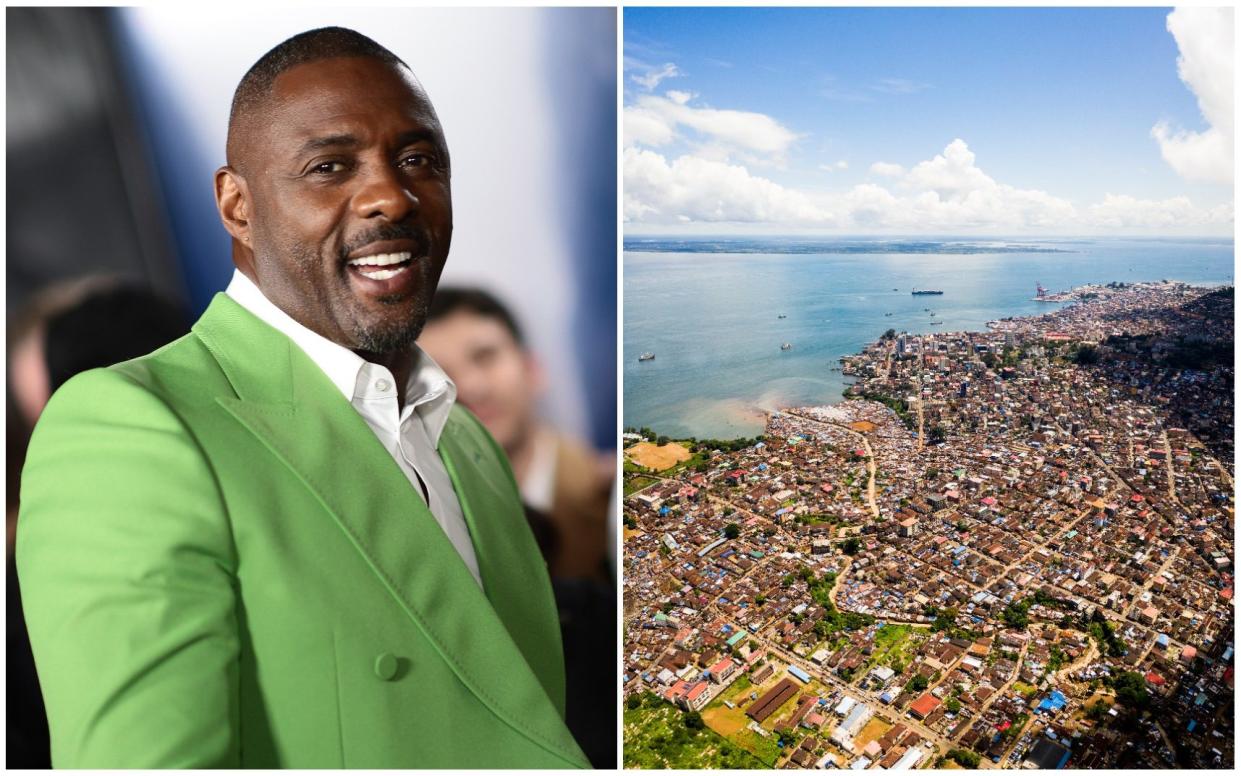

Pitbull promoted Florida. Jackie Chan told tourists to try Hong Kong. And now Idris Elba is helping bring direct flights to Sierra Leone. Alongside brilliant hotels and a vibrant culture, it seems as if tourist destinations think a celebrity endorsement is crucial for people booking a holiday.

Luminaries who have depicted the UK include Judi Dench, Rupert Everett, Jamie Oliver, Twiggy, Dev Patel, Stephen Fry, Wallace and Gromit and more. Most of these were recruited for Visit Britain’s 2012 campaign, which, as one-time marketing director Laurence Bresh says, was a “unique year” – encompassing the then Queen’s Diamond Jubilee and the London Olympics.

It was as a result of these circumstances that Visit Britain was given a bumper budget, totalling some £125 million. The initial success of the first films – in which Judi Dench celebrated the country’s “abundance of stately homes” and Dev Patel praised “buzzing” Leicester Square – led to a further injection of cash, culminating in the “Great” campaigns that are still used at UK airports.

The need for something eye-catching, and A-list, was not totally about prestige.

“One thing we were surprised by when we started was that visitor numbers typically go down during the Olympics year. People tend to stay away,” says Bresh, who worked as Visit Britain’s marketing director at the time.

The question, though, is whether or not celebrity-endorsed campaigns actually work. It is hard to imagine that an endorsement from Jack Grealish would inspire seasoned travellers to make a change. Likewise, a recommendation from Michael Caine might not sway a young holidaymaker to discover a new country. And yet tourism boards so regularly use A-listers to promote their destination.

It certainly worked for Visit Britain. In 2012, some 12 million inbound tourists visited the country, a five per cent increase on the previous year. By 2014, the campaign recorded a £1.2 billion return on investments.

For an event as nationally significant as the Olympics, the Union flag festooned imagery felt appropriate. But some campaigns lean into the inherent weirdness of a celebrity – a single person – representing a whole country. Kazakhstan incorporated Sacha Baron Cohen’s Borat into its campaigns. A Mark Zuckerberg impersonator appeared in an ad for Iceland. The rapper 50 Cent created a video for Hostelworld.

The Visit Britain campaign was over a decade ago, and the power of celebrity endorsement has changed. Dr Vincent Mak, a professor of marketing at the Cambridge Judge Business School, thinks that technology has fundamentally changed the way destinations are marketed.

“Social media means that you can reach so many more people than a traditional campaign would. Just one Instagram post from a celebrity can mean so much more exposure than we were once capable of,” he says.

Tens of thousands, perhaps millions, more people will see Chris Hemsworth promote Australia, or Taika Waititi suggest New Zealand as a place for a holiday, or Roger Federer suggest Switzerland, if the images are posted to their social media.

Unlike a billboard campaign, the internet allows two-way communication. “Therefore, if the public really likes what you’re doing it can become a runaway hit overnight, or even [within] a couple of hours. It can also become a disaster pretty quickly,” says Mak.

The less “authentic” the endorsement feels, the more likely the disaster. An advert from Beyoncé recommending a stay at a Butlins would not feel believable. And so the ideal celebrity promotion is one that comes about without the involvement of a tourist board at all. Rather than being asked – and likely paid – to say they enjoy holidaying in Paris, it feels more genuine for a celebrity to mention that they love the 18th arrondissement. By its very nature, this is something that tourist boards dream about, but have no control over.

Perhaps the most successful example of this is Rihanna’s relationship with her home country, Barbados. In the first flush of her fame, the singer took part in an official campaign: running along the beach, riding a bicycle on a country lane and playing dominoes with locals. The adverts cemented her association with the island, but it was afterwards – on real trips home, in song lyrics, and even during her Superbowl performance – that the link really developed.

Cheryl Carter, a director for the Barbadian tourist board, evidently appreciates the country’s most famous daughter. “We’re very, very proud of Rihanna, and all that she has accomplished,” she says. “And I think Rihanna has been very clever to continue to position herself as an island girl, because it’s what sets her apart from the pack.”

Last year the singer stopped for snow cones at a stall near her villa. “Suddenly the snow cone seller’s popularity just blew up,” says Carter.

She is keen to point out that celebrities have always been drawn to Barbados, but the connection with the singer has encouraged other A-listers to see it as a holiday destination – and has opened up the destination to a new group of travellers.

“It’s certainly helped us to reach a much younger demographic,” says Carter. “I remember flying into New York once and going to a car rental. And the young man there, he couldn’t have been more than 21 or 22. I gave him my driving licence, and he said, ‘Oh, you’re from Rihannaland’.”

It’s the sort of thing tourism boards dream of. Even the most cynical of holidaymakers would believe in Rihanna’s genuine love for the island – and perhaps consider a trip.

There are, however, risks involved when employing celebrities. “It’s a game,” says Dr Mak. “There’s high gain, but also high risk as well. Some celebrities can be quite controversial.

“People’s reputation goes up or down so much more quickly and so much more drastically than before.”

Messi’s continued relationship with Saudi Arabia has drawn ire from some quarters, with commentators pointing to the country’s human rights record – and allegations of “sports washing” – as reasons the footballer shouldn’t have taken the role.

Most notorious, though, is the “Pitbull incident”. In 2016, the rapper was engaged by Florida’s tourism department. As part of the contract, Pitbull filmed the music video for his song Sexy Beaches in the state, which included iconic Floridian hotels like Miami’s Fontainebleau – and ended on the “#LoveFL” slogan.

So far, so typical for Mr Worldwide. But it transpired he had been paid $1 million (funded in part by taxpayers) for the campaign, something that only came out after government officials pressed the rapper to disclose details of his contract. The marketing agency behind the campaign was subsequently given new management.

It doesn’t seem as if the state of Florida’s image as a tourist destination was particularly tarnished. So do endorsements really change where we holiday? Dr Mak thinks that the campaigns are “a matter of awareness” that probably make us more likely to consider a destination – but not necessarily book it. “Finally reaching a decision as to where to go could be interrupted by so many other factors.”

If you don’t like spending time on the beach or long-haul flights, you probably won’t be booking a trip to Barbados, no matter how much Rihanna loves it.