Canadian dairy farmers urged to think about bird flu protections as U.S. identifies 2nd case

As the U.S. identified a second human case of bird flu linked to dairy cows this week, some Canadian dairy farmers and veterinarians are on guard, taking measures like stocking up on personal protective equipment.

The latest patient, a farm worker in Michigan, had mild eye symptoms and has recovered, state health officials said. In March, the first patient, a dairy farm worker in Texas, had eye redness and discomfort.

The H5N1 virus that's at the centre of the current outbreak is deadly to birds; in cows, it's resulted in decreased milk production, loss of appetite and fever.

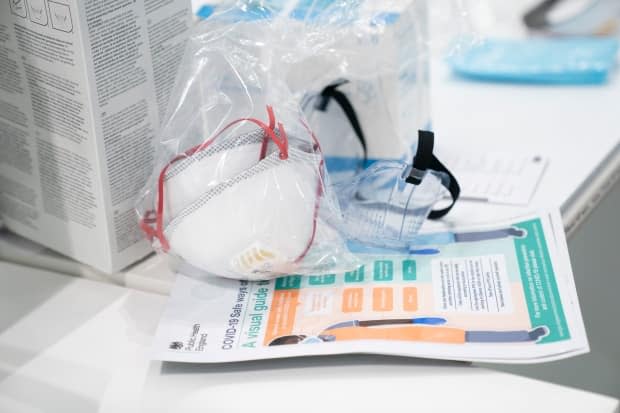

Earlier this month, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommended that jurisdictions make PPE available to dairy and poultry farms with infected animals to avert infections, and affected states began offering supplies.

The virus has not yet been detected in Canadian dairy cattle, and all tests of commercial milk for fragments of H5N1 have also been negative, according to the Canadian Food Inspection Agency.

But if cows in Canada do become infected with H5N1, then gloves, goggles and masks could join work boots and coveralls in farmers' wardrobes here.

Advisories for a large dairy industry

There are 11,000 dairy farms across the country. Quebec alone has more than 4,300 dairy farms, and Ontario's industry supports nearly 86,000 jobs.

To try to keep the virus out, the Public Health Agency of Canada is advising people who have close contact with animals or work in contaminated environments to take precautions such as:

Wear eye protection and masks to block your eyes, nose and mouth from contaminated dust, feathers, secretions and feces.

Wear protective clothing, like gloves, boots and coveralls.

Before cleaning up contaminated areas, mist dry areas with low-pressure water to prevent potentially infected material from being stirred up into the air.

Change clothing and footwear, and wash hands thoroughly with soap and water.

Which provinces provide PPE?

CBC News reached out to some provincial health and agricultural officials to find out if they provide PPE without farmers having to pay for it themselves. Ontario said it already does.

"Farmers can order the necessary PPE for free, including delivery to the farm, from Supply Ontario," a spokesperson said.

Yet as of May 15, no orders had been received, they said.

Farmers may also contact their local public health unit or the Ontario agriculture ministry for support on ordering the supplies.

In statements, Quebec, British Columbia, Alberta, Manitoba and P.E.I. said they do not offer PPE to farmers.

After identifying risks to workers, employers must implement appropriate measures, said the Canadian Centre for Occupational Health and Safety.

'I would protect myself,' farmer says

Dairy producers routinely monitor the general health of their herds to protect their animals and bottom line.

At Marcus and Paige Dueck's dairy farm in Kleefeld, Man., about 60 kilometres south of Winnipeg, the couple take extra precautions when the animals are ill.

"It's like most diseases, you care for the sick and protect yourself," she said. "We've all been through COVID and understand how that works, and it's no different in agriculture."

The Duecks' 50 brown Swiss cows are milked three times a day by a robot that drives to each cow's stall.

The robotic milker also collects data on animal health, such as the amount and quality of milk, and an increase in white blood cells, which may indicate sickness.

If anything seems off, Paige does a physical exam manually, quarantines the sick animal, pours the milk out as required by law and waits for the infection to clear.

If a cow were sick, she'd don PPE to prevent potential spread from milk or feces splashing into the mucous membranes lining her eyes, nose or mouth.

"I don't need a discomfort like pink eye or a strong cough from my cow, so I would protect myself."

As for the cow, any infection that causes a high fever results in the animal producing less milk while they recover. From a productivity point of view, an outbreak of H5N1 could be devastating to her business, she said.

WATCH | Canada's retail milk checked for H5N1 fragments:

In a report into an outbreak of highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) on a dairy farm in Michigan, the farmer said infected cows spiked a fever, resulting in severe dehydration, far less milk production and the need to hire more workers.

The Duecks also take biosecurity precautions such as not bringing in outside animals, removing potentially contaminated food sources like spilled grain and draining low-lying areas to avoid attracting migratory birds that could introduce the virus.

In the U.S., while the National Milk Producers Federation said it encouraged farms to use protective equipment, three dairy workers, seven activists and two lawyers who assist farm employees told Reuters that dairy owners have not offered equipment like face shields and goggles to staff.

Positive case could help PPE compliance

Dr. Simon Dufour, a veterinary epidemiology professor at the University of Montreal, said it could be a hard sell to ask farmers to wear goggles and a mask in a humid barn, when Canada has no detected cases of H5N1 in cattle.

"If there was a positive herd, I think … most people would comply," Dufour said.

Dufour has worked with commercial dairy farms in Quebec and B.C. and now does research on how infectious diseases pass between cows in a herd and between herds.

It's not just farmers who would need PPE — milk collectors and veterinarians would need the gear, as well, he said.

As a veterinarian, Dufour said key unanswered questions include how long cattle shed the virus for and whether some cows could have asymptomatic infections.

Since the virus could mutate into a form that easily infects humans and causes more severe illness, surveillance is critical.

"You want to make sure that everybody is prepared to act correctly if there was a herd that would become infected," he said.

Dairy industry groups have been offering webinars to spread the word on precautions.

An Alberta agriculture ministry spokesperson said the U.S. dairy cases "are a strong reminder to Alberta's livestock producers of the importance of strict biosecurity measures, including PPE, and early detection."