Building America: the incredible history of Washington DC

Building America’s capital

Sean Pavone/Shutterstock

Founded near the end of the 18th century on the north bank of the Potomac River, Washington DC is the only city in the US to owe its very existence to the Constitution. Simultaneously a paragon of political process, an incubator for protest and social justice, a cosmopolitan capital, a living history museum and a bustling tourist destination, this unique city has seen triumph and tragedy to match that of America itself.

Read on to discover the fascinating history of Washington DC...

Before DC

Peterpietri/Wikimedia Commons/Public domain

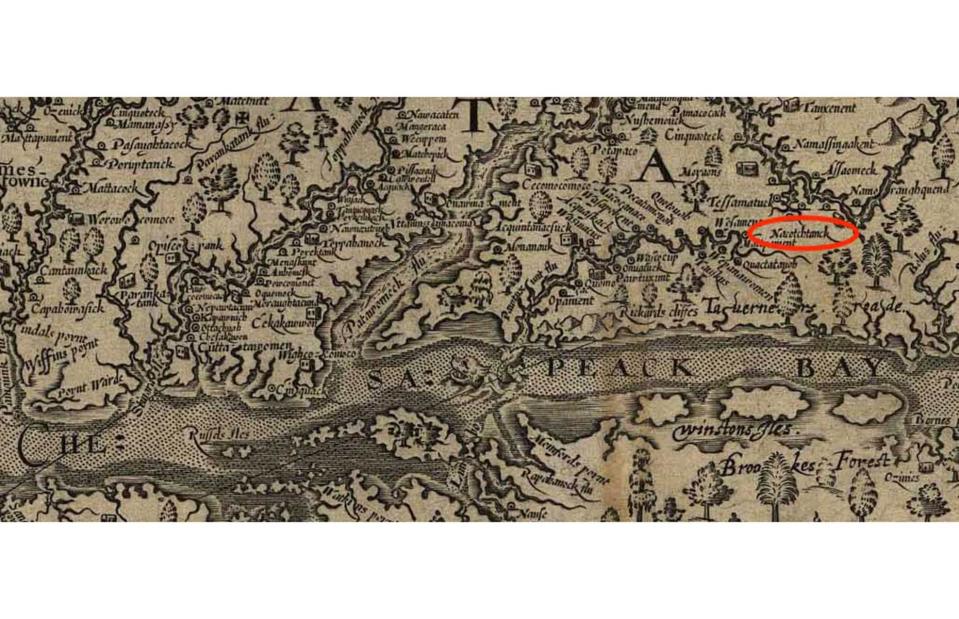

The lands on which the American capital sit are the ancestral home of the Anacostans – Native Americans who lived in the village of Nacotchtank, circled here on Captain John Smith’s map from 1624. Their name comes from the Anacostia River, which joins with the Potomac in DC. When European settlers arrived in the 17th century, disease, conflict and relocation saw local Native American populations shrink to a mere quarter of their pre-colonial size in just four decades. This history is often undermined by the heavily romanticised story of Smith, the first European to explore the region, and Pocahontas, daughter of the local Chief Powhatan.

First port of call

elisank79/Shutterstock

Prior to 1790, what is now Washington DC was part of the states of Maryland and Virginia. With the arrival of Europeans came a boom in tobacco plantations, giving rise to port towns like Alexandria (in Virginia) and Georgetown (pictured), enabling maritime trade. Georgetown – founded in 1751 – is the oldest neighbourhood in present-day DC, having been ceded by Maryland when the District of Columbia was first created. Many of its historic buildings, including Tudor Place and Dumbarton House, are open to visitors.

A presidential pick

Kurz & Allison./Wikimedia Commons/Public domain

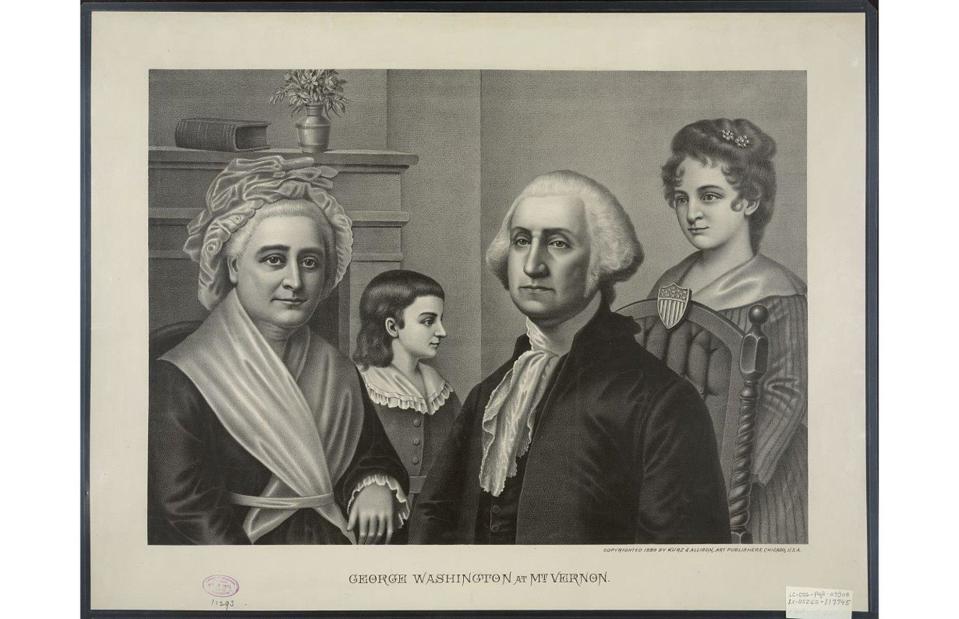

Following the American Revolutionary War in 1775-83 and the ratification of the US Constitution in 1788, the Founding Fathers sought to establish a permanent capital and seat of government for their new, independent nation. It was President George Washington (pictured here in a family portrait) who identified a site on the Potomac and Anacostia Rivers as its potential home, as the location could bridge the Northern and Southern states and connect the inland frontiers to the sea. Sadly, he is the only president never to have lived in Washington DC, having retired and passed away before the presidential residence was ready.

North versus South

John Trumbull/Wikimedia Commons/Public domain

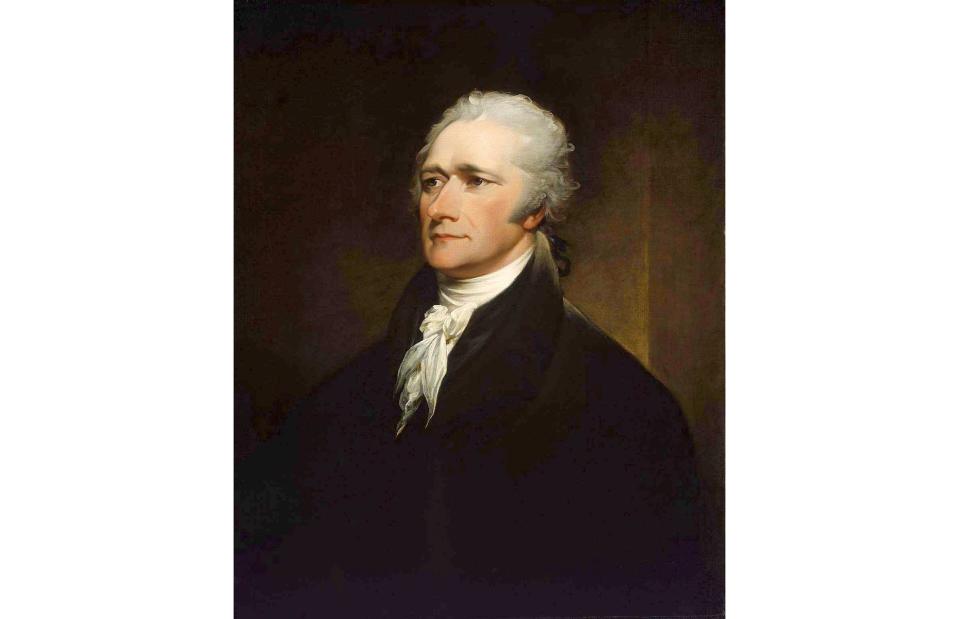

Washington’s choice of location divided his congressmen. Alexander Hamilton (pictured) stood with America’s North, and did not want a capital located between the pro-slavery states of Virginia and Maryland, while slave-owning Southerners Thomas Jefferson and James Madison pushed for the location proposed by the president. The issue of national debt following the Revolution was also a sticking point, with Hamilton (as secretary of the treasury) believing that the government, rather than individual states, should be responsible for assuming it.

Adopting the Residence Act

US Government/Wikimedia Commons/Public domain

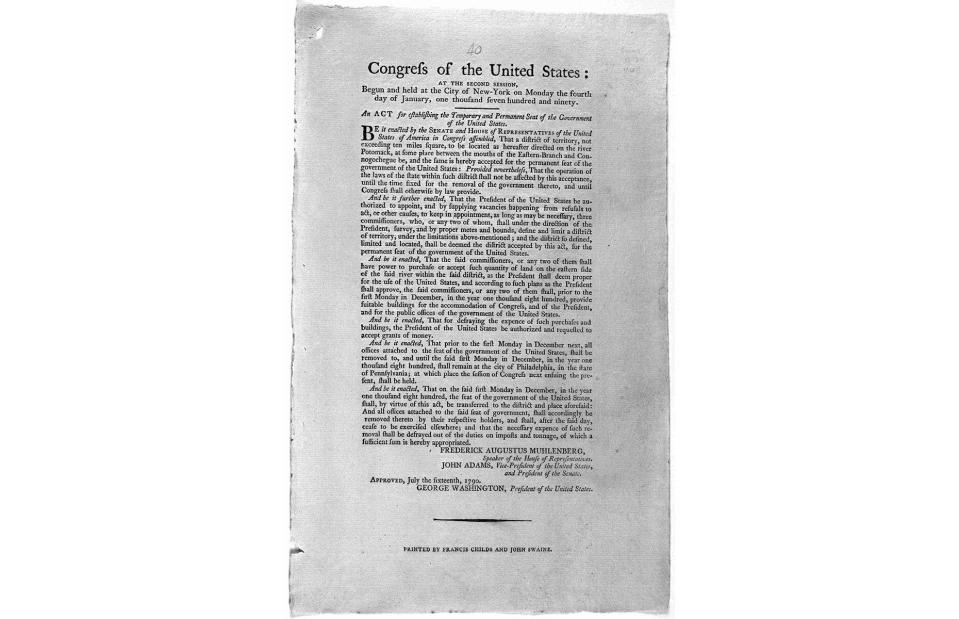

In June 1790 the three congressmen held a secret meeting and struck a deal. Known as 'the dinner table bargain', Madison agreed to encourage Southern support for federal debt assumption in exchange for Hamilton backing the Potomac location for America’s new capital. There is some debate over exactly how much this meeting contributed to the history-making compromise, but the Residence Act (pictured) was nonetheless passed in July 1790, recognising what would become Washington DC as the nation’s purpose-built capital. The Funding Act – approving Hamilton's debt assumption measures – was adopted a month later.

Breaking ground

Steve Heap/Shutterstock

The birthplace of American independence, Philadelphia served as America's temporary capital while DC was being built. To build the new capital, tracts of land belonging to Virginia and Maryland on both sides of the Potomac were transferred to the federal district, including the ports of Georgetown and Alexandria (pictured). This distinct territory was soon named the District of Columbia (DC) after the explorer Christopher Columbus. During the mid-19th century the land originally ceded by Virginia on the south bank of the river was returned to the state, bringing DC to its current size of around 68 square miles (177sq km).

Child of the Revolution

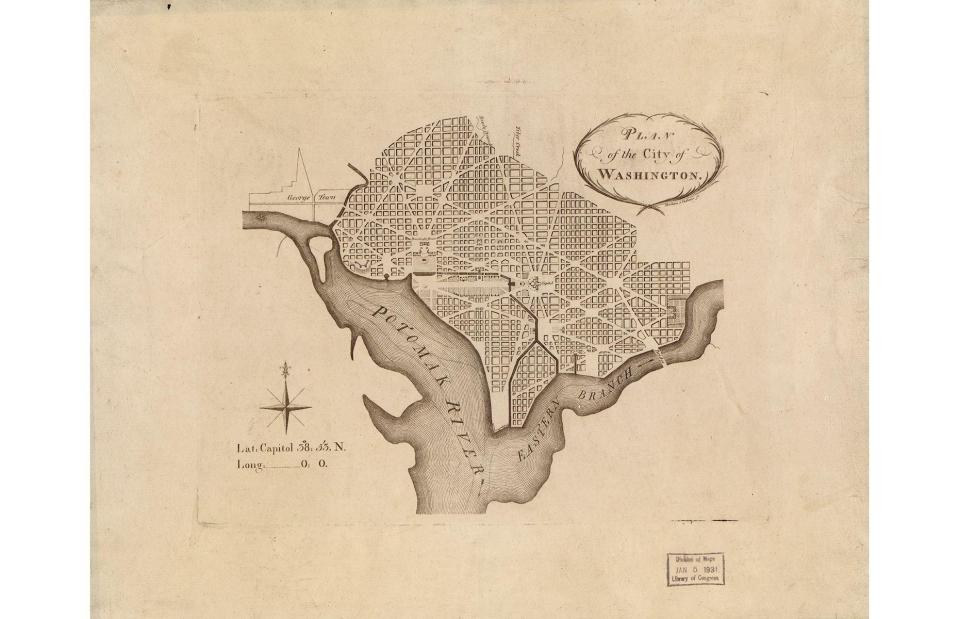

Library of Congress/Wikimedia Commons/Public domain

The planning of the new capital – named for the nation’s first and then-current president – was entrusted to Pierre Charles L’Enfant in 1791. A French-born engineer, architect and Revolutionary War veteran, L’Enfant had previously renovated New York City’s Federal Hall alongside various other smaller jobs. His vision for Washington DC took inspiration from the diagonal avenues, grand architecture and plazas of Europe’s finest cities. He picked a high ridge as the site for the US Capitol, which would become the centre of a sprawling grid system.

Precision planning

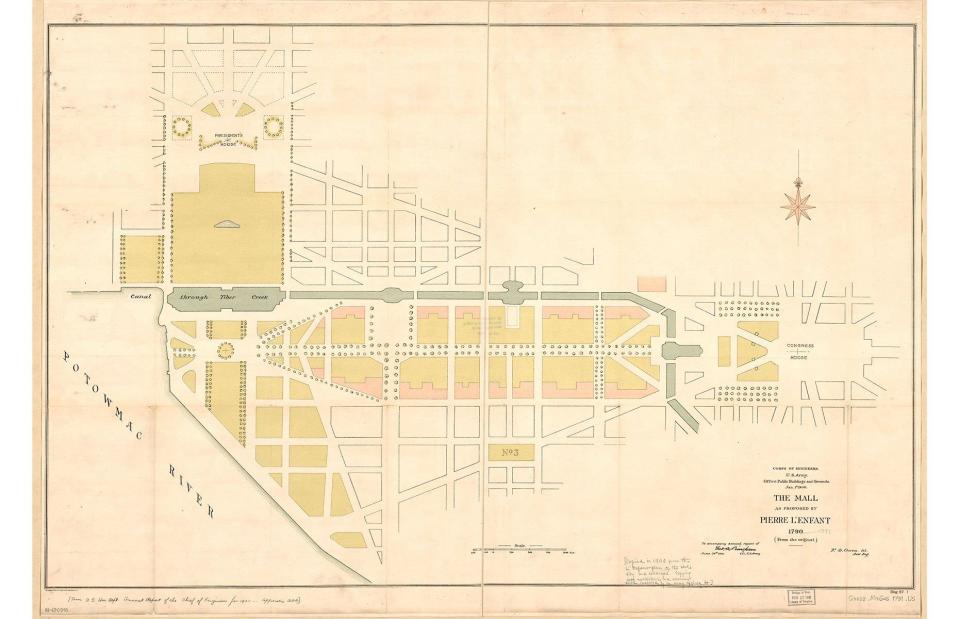

Library of Congress/Wikimedia Commons/Public domain

Turning a rural blend of hills, forests, marshes and plantations into a major metropolis required minute precision. Andrew Ellicott and Benjamin Banneker (a free Black man and self-educated astronomer) surveyed the land on which the capital would be built, while L’Enfant divided the city into quadrants. Radiating from Capitol Hill, he laid out wide boulevards and an early iteration (pictured) of what is now the National Mall. These wide avenues, many of which are named after states, cross-cut the grid of city blocks to create triangles, circles and squares.

Fall from grace

Arlington National Cemetery/Wikimedia Commons/Public domain

L’Enfant’s ambition and bold ideas also became his downfall. Compromise notably gave birth to this historic city, and L’Enfant’s inability to cooperate with its commissioners led to his ultimate dismissal from the project. Though his plans for the capital’s development were generally followed in his absence, L’Enfant was never properly remunerated for his efforts and he died penniless in Maryland. His body was reinterred in 1909 at Arlington National Cemetery in Virginia, where Congress erected a monument to him overlooking DC (pictured).

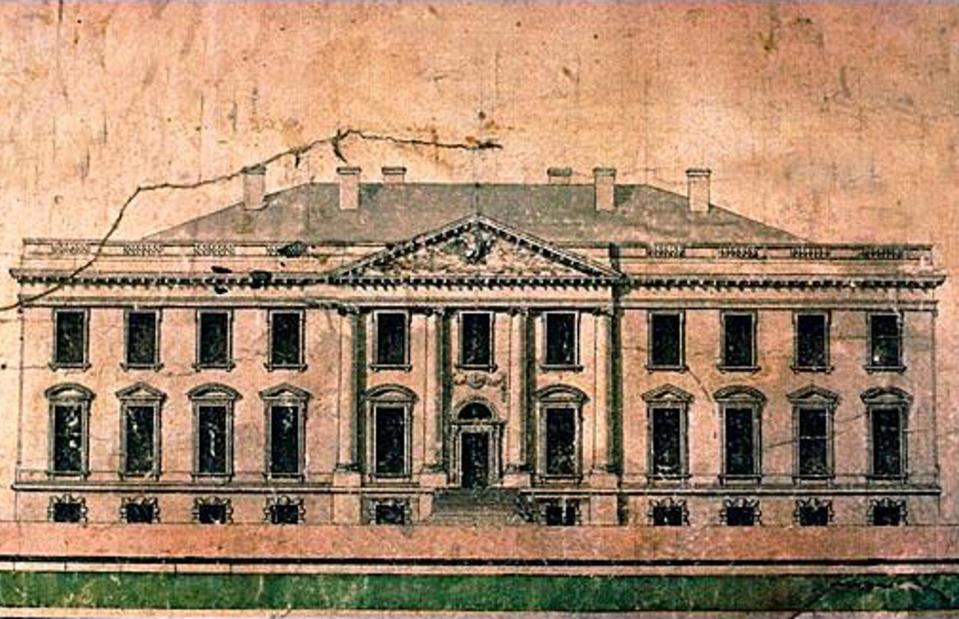

A presidential palace

Maryland Center for History and Culture/Wikimedia Commons/Public domain

Though fate determined he would never live in it, George Washington oversaw the construction of DC’s presidential mansion. It was mostly designed by James Hoban, originally from Ireland, who won a contest to build the project with an idea inspired by Dublin’s Leinster House. Work began on the sandstone structure in 1792, which was later coated with lime-based whitewash, sowing the seeds for the building’s famous nickname. Second US president John Adams became the first occupant of the still-unfinished White House in November 1800, for what would be the last four months of his presidency.

Congress convenes

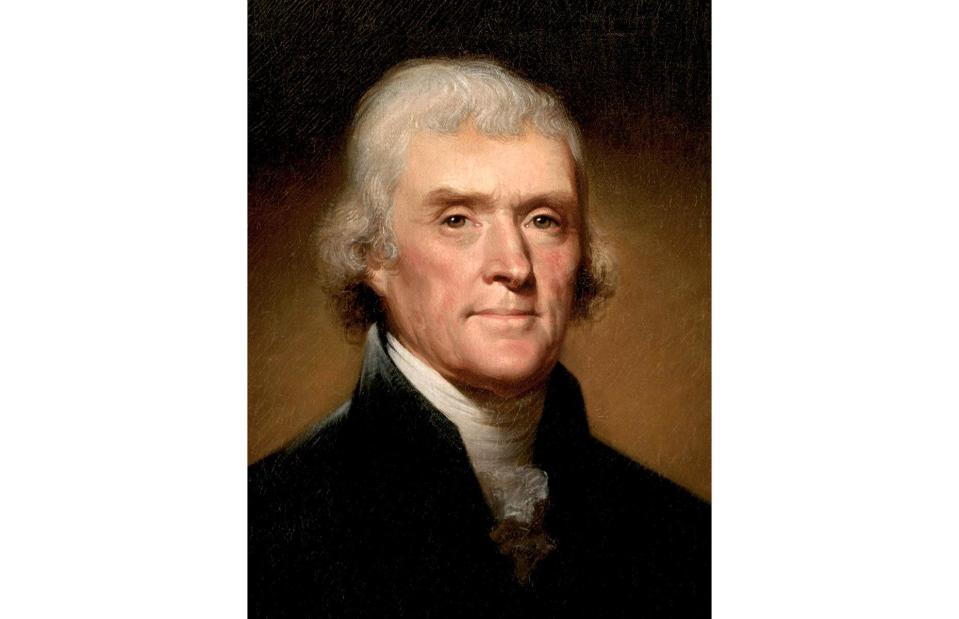

Rembrandt Peale/Wikimedia Commons/Public domain

George Washington laid the cornerstone for the Capitol building on 18 September 1793. L’Enfant had been set to design the Capitol himself, but left the project before submitting plans. The final design was a culmination of several architects’ work over the years, from William Thornton’s original Georgian exterior to Benjamin Latrobe’s Corinthian columns. The north wing was completed first, with Congress meeting there for the first time in November 1800. The following year, third US president Thomas Jefferson (pictured) became the first to be inaugurated at the Capitol, a tradition that's continued ever since.

Capitol gains

US Capitol/Wikimedia Commons/Public domain

In time, the Capitol’s north wing became the meeting place of the Senate, while the south wing – completed in 1807 – contained the chamber of the House of Representatives. Philadelphia architect Thomas Ustick Walter oversaw a major extension and reimagining of the building in the mid-19th century, adding the iconic, 4,500-tonne cast-iron dome (pictured). The Capitol has endured fire, war, shootings, bombings and stormings in its 200-year history, but it is nevertheless simple for civilians to visit. Tours are free but must be booked in advance.

DC’s dark side

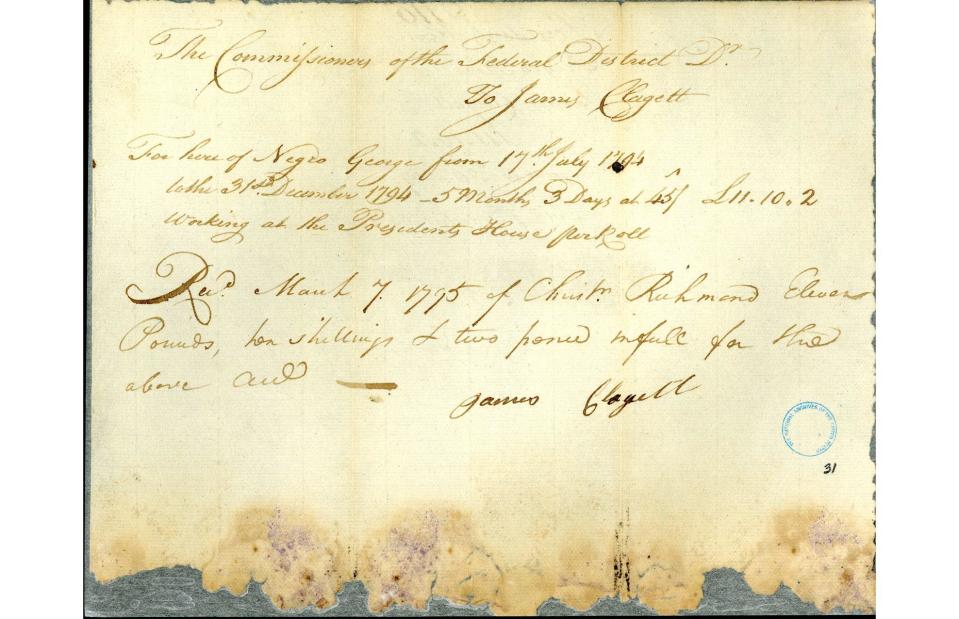

National Archives, Records of the Commissioners of the City of Washington (Record Group 217)

The Capitol and White House were nearing completion when Congress moved from Philadelphia to Washington DC in 1800. But did you know these two world-famous landmarks were built with enslaved labour? The National Archives, located in DC, contain evidence of wage rolls, promissory notes and vouchers (pictured) that place enslaved African Americans among the buildings’ construction workers. Then-First Lady Michelle Obama spoke on this at the 2016 Democratic National Convention, describing the complex feelings of waking up in the White House each morning as a Black woman.

Up in flames

Paul M. Rapin de Thoyras/Wikimedia Commons/Public domain

Before DC could really come of age, the burgeoning city was almost wiped off the map. During the War of 1812, British forces captured the capital and in 1814 enacted what became known as the Burning of Washington – this illustration from 1816 recounts the harrowing attack. The newly completed White House and the Capitol were set alight, with the Library of Congress and its original collection of 3,000 books lost to the blaze. Before evacuating the White House, First Lady Dolley Madison is said to have saved a full-length portrait of George Washington and a copy of the Declaration of Independence.

Like a phoenix

George Munger/Wikimedia Commons/Public domain

As the smoke lifted, lawmakers discussed the possibility of moving the capital elsewhere. But instead DC was gradually restored; the White House, largely reduced to ash, was rebuilt by its original architect, who incorporated some of its blackened walls into his design. The Capitol (pictured) was reconstructed too, and in 1815 Thomas Jefferson sold off his own personal book collection to replenish the shelves of the Library of Congress. By 1817 the White House was again ready to welcome the president, while Congress returned to the Capitol two years later.

Educating America

Kit Leong/Shutterstock

The mid-19th century was a period of great social, industrial and cultural development in Washington DC, with railroads, new federal buildings and tourism shaping the growing city. One of this era’s milestones was the founding of the Smithsonian Institution, funded by the fortune of deceased British scientist James Smithson. The largest museum, education and research complex in the world today, the Smithsonian looks after 17 museums and galleries in DC alone, including the National Zoo, the National Museum of Natural History (pictured) and the National Museum of African American History and Culture.

The Civil War years

Maurice Savage/Alamy

However, this chapter of DC’s past was also fraught with racial tension and mounting conflict over slavery. The American Civil War began in 1861 and lasted four years, with the capital – protected by its own army – never far from the frontline, as it bordered the Confederate stronghold of Virginia. DC had become one of the world’s most fortified cities by the war’s end, encircled by 68 forts and 93 batteries boasting more than 800 cannons. Some of the surviving sites, such as Fort Stevens (pictured), are managed by the National Park Service and are now open to the public.

Land of the free

Orhan Cam/Shutterstock

DC abolished slavery in 1862 after President Abraham Lincoln signed the District of Columbia Compensated Emancipation Act into law. Slave-owning citizens were financially compensated for each freed person, and around 3,000 emancipated individuals boosted the capital’s population, which had plummeted after Virginia reclaimed land from the district in 1846. The city subsequently became a haven for those freed from bondage, and in the years since has erected more memorials to the Civil War than it has to any other period in US history.

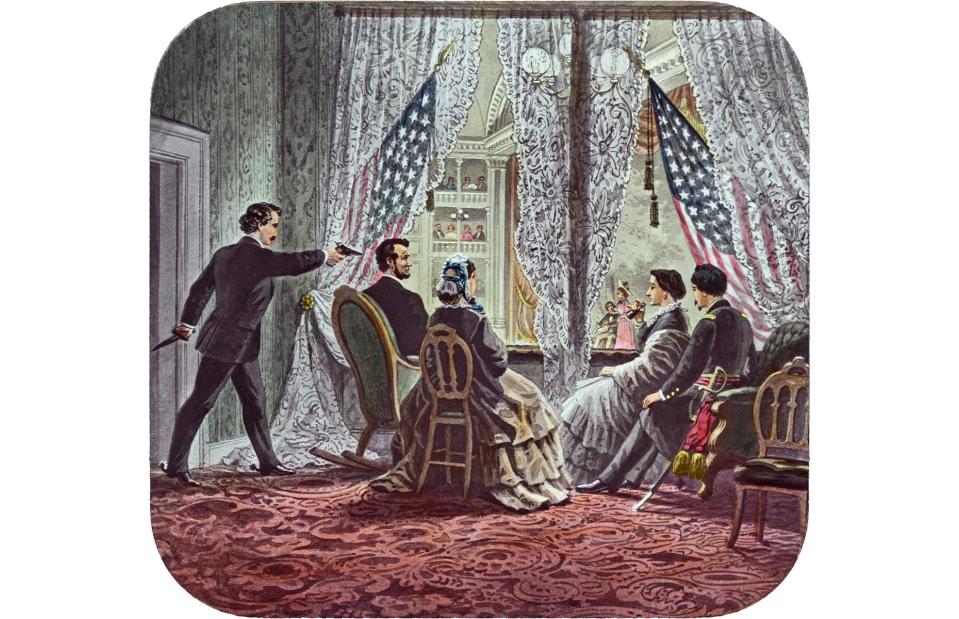

A fateful night at Ford’s Theatre

Heritage Auctions/Wikimedia Commons/Public domain

The North won the Civil War, but in the capital the joy was short-lived. On the night of 14 April 1865, Confederate sympathiser John Wilkes Booth entered President Lincoln's box at Ford’s Theatre in DC as he was enjoying a performance of Our American Cousin, and shot him in the head at point-blank range. The president died the following morning. Initially there were calls to have Ford’s Theatre destroyed, but it remains a working theatre and today houses the Lincoln Museum in its basement, which covers the events surrounding the assassination.

Remembering 'the father of his country'

Mathew Benjamin Brady/Wikimedia Common/Public domain

The cornerstone for this granite and marble obelisk – dedicated to its namesake president – was laid on Independence Day 1848, though it would be another 40 years before the Washington Monument opened to the public. This photo shows its progress around 1860. On completion it was the tallest man-made structure on Earth (though only briefly), and it remains the world's tallest unreinforced masonry structure at 555 feet (169m). In August 2011, a 5.8-magnitude earthquake shook the monument, flooring visitors on the observation deck and pelting them with falling stones. It was painstakingly restored and reopened in May 2014.

Moving with the times

Life Atlas Photography/Shutterstock

Following the Civil War, Washington DC flourished. Schools, markets, paved roads, sewers and outdoor lights were installed, and more than 50,000 trees were planted. DC began attracting wealthy intellectuals who made the city their winter retreat, cultivating its arts and social scenes. Then, in 1901, the Senate established the McMillan Commission, which modernised the capital using L’Enfant’s original framework as a base. The most significant improvements were to the National Mall (pictured), which was straightened and expanded.

Memorials and monuments

jdjohannsen/Shutterstock

Among DC's most-visited memorials are those of past presidents. The Lincoln Memorial (pictured), modelled on the Parthenon in Athens, was dedicated in 1922 and contains a 19-foot (6m) marble statue of the man himself. South of the National Mall is the Jefferson Memorial, a round building influenced by Rome's Pantheon that was dedicated in 1943 in the midst of the Second World War. The city also has memorials to various wars involving US forces, including the Vietnam War and the Korean War, as well as more equestrian statues than any other US city.

Black history in DC

GL Archive/Alamy

After the abolition of slavery Washington DC retained a large African American population, and is today associated with a number of notable African American figures. Frederick Douglass, a formerly enslaved man who became a leading reformer and equal rights activist, was based in the city. It was also the birthplace of celebrated jazz musician Duke Ellington (pictured), who was raised in the Shaw neighbourhood and played with his first band there. By the 1920s, DC was home to more African Americans than any other city in the US, but it was no more immune to the issues of racism and segregation.

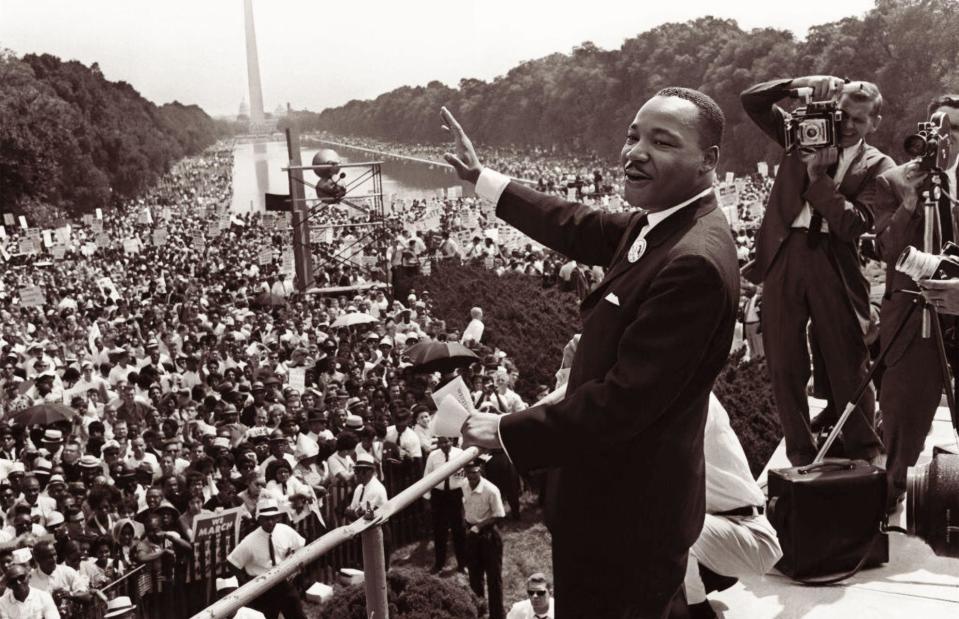

"I have a dream"

Alpha Historica/Alamy

One of the worst race riots in US history happened in DC in 1919, during a period of unrest known as 'the Red Summer'. Black servicemen returning from the First World War were attacked by white mobs in the capital’s streets, inflaming racial tensions and paving the way for the civil rights movement in the mid-20th century. On 28 August 1963, Martin Luther King Jr delivered his history-making "I have a dream" speech in front of the Lincoln Memorial, part of the March on Washington protest that drew crowds of around 250,000. A national memorial to King stands near that famous site today.

A witness to world events

Glasshouse Images/Alamy

The 20th century also saw DC grow rapidly, and added several new pages to its history books. President Woodrow Wilson, pictured here at DC’s Preparedness Day parade in 1916, brought the US into the First World War and later formed the League of Nations. Franklin D Roosevelt’s historically long presidency (1933-45) included the completion of the Pentagon – technically in Arlington, Virginia on the other bank of the Potomac. In 1981, President Ronald Reagan remarkably survived an assassination attempt when he was shot outside the Washington Hilton Hotel.

Making a modern city

Imago/Alamy

From political scandals to deadly plane crashes and devastating floods, Washington DC’s story is nothing if not turbulent. But by its 200th anniversary in 1990 the capital had evolved from a small town into a vast metropolis and world city. It had also become a battleground for activism on which the values of peace, tolerance and equality were passionately and frequently debated. One of the city’s most moving displays was when the AIDS Memorial Quilt (pictured) was unveiled for the first time on the National Mall in 1987. Each of the quilt's 1,920 panels was inscribed with the name of a person lost to the AIDS epidemic.

The struggle for home rule

f11photo/Shutterstock

Despite living in the lap of the world’s most powerful democracy, Washingtonians lack full self-governance. The district elects one non-voting delegate to the House of Representatives and has no official senators, while residents of the capital couldn’t even vote in presidential elections until the 23rd Amendment allowed them to do so in 1964. DC has only been able to elect its own mayor and city council since the 1970s, and questions around its governance and potential future statehood remain divisive today.

Spoilt for choice

Orhan Cam/Shutterstock

With so many things to see and do in Washington DC, where do you even start? The grand museums of the Smithsonian and the thought-provoking monuments of the National Mall are popular for good reason. But from jazz festivals, sculpture gardens and art galleries to park walks, Potomac cruises and a tour that combines history with doughnut tastings, there’s so much more going on. Opening later this year, the Go-Go Museum honours the unofficial music of DC – a mix of funk, R&B, hip-hop and Afro-Latin rhythms born in the city in the 1970s.

Believe it or not

Kent Nishimura/Getty Images

Did you know that a hidden 700-foot (213m) tunnel runs under the National Mall? Off limits to the public, it connects the Smithsonian Castle to the Natural History Museum. Also, due to building height restrictions, there are no huge skyscrapers in DC like the ones in New York and Chicago. But the city does have the world’s largest collection of printed works by William Shakespeare, housed in the Folger Shakespeare Library (pictured), which reopens this year after a long renovation. DC also has a quirky Easter tradition – the White House Easter Egg Roll. Participation in the competition, first started on Capitol Hill in the 1870s, is decided by a lottery.

The city in bloom

Sean Pavone/Shutterstock

A gift from Japan to America in 1912, the annual blossoming of Washington’s candy-coloured cherry trees has become one of the most anticipated events in the capital’s calendar. Cradling DC’s Tidal Basin, the trees’ pink and white petals signal the arrival of spring and mark the beginning of the four-week-long National Cherry Blossom Festival, where visitors come from all over the world to enjoy the practice of hanami (flower viewing). The trees typically reach peak bloom between mid-March and early April.

Now check out these intriguing facts about US history you probably didn’t know