A brain expert explains the cognitive test used to assess a president's mental fitness. It's not easy.

A psychologist who checks business leaders and doctors for cognitive decline shared how he does it.

His assessment takes about an hour, and involves a lot more than just one test.

It's pretty challenging.

Most Americans think 81-year-old President Biden is just too old to be president.

There are also concerns about 78-year-old Republican nominee Donald Trump's fitness for office — registered voters are split on whether he still has the cognitive skills for this job.

But brain aging experts say the candidates' chronological ages are, to some extent, a red herring.

"There's this widespread belief that older people lose it, but it's really less to do with chronological age per se, and more to do with all the crappy things that your age puts you at greater risk for," neuropsychologist Joel Kramer, the director of the Memory and Aging Center Neuropsychology program at the University of California, San Francisco, told Business Insider.

"It's really no different than your knees. Just because you're older doesn't mean you're going to have bad knees, but there are a lot of older people with bad knees."

There are some quick assessments that only take doctors a couple of minutes to administer in the clinic, giving them a general sense of how you're doing. You might've heard of a few of these in recent political coverage.

The Mini-Cog test requires you to repeat and then remember a few spoken words, and draw a clock correctly with a specific time of day on it, testing not only basic memory skills but also visual spatial control and other key brain functions.

MoCA: The Montreal Cognitive Assessment (Trump took it six years ago when he was President.) Like the Mini-Cog, there is some clock drawing, repeating and recalling, as well as naming simple pictured objects like a lion and a camel.

SAGE: A self-administered home test designed by The Ohio State University.

These aren't perfect tools, though, and aren't really what a doctor would use to determine whether someone is mentally fit enough to hold a high-powered job. These tests are rudimentary, and people with dementia can pass them, especially if they are still in the early stages of a disease — all of us are good at masking subtle memory issues, Kramer said. ("When was the last time you ran into someone whose name you couldn't quite come up with, and you faked it for a while?")

Kramer says a full clinical assessment checking for neurodegenerative issues usually takes about an hour, or longer.

He gave me a taste of how clinicians suss out a person's ability to learn and retrieve new information, multitask, and perform age-appropriate motor skills.

A true cognitive evaluation should be challenging

"I'm going to read a list of words to you," Kramer said. "Listen carefully, and when I'm through, say back as many of them as you can: hat, berries, wrench, sweater, lemon, pliers, belt, peaches, drill."

This exercise can be adjusted based on a person's age and ability. (Kramer said if we were really doing this, he'd give me a much longer list.)

Later on in the session, the clinician might ask you to recall, "Hey, what was on that list again?" It's a test you can't really cheat on, since the words aren't written down anywhere, and can easily change from session to session.

I found the multitasking part of his assessment more challenging:

"I'm going to say some numbers, when I'm through, say them to me backward: 4, 9, 2, 6, 3."

I know it looks easy written down here, but remember, he's just saying this out loud. You have to keep the list straight in your head, while also repeating it from back to front. I did pretty terribly:

"3, 6, 4 …" Whoops.

Multitasking gets a bad rap — we've all heard it's bad for focus and, in some ways, biologically impossible. But the more complicated truth is we are actually doing certain forms of multitasking all the time, and some of them are telltale signs of a healthy, well-functioning brain (walking and talking, for example).

The particular kind of multitasking being tested here is a critical skill for a good leader. You need to be someone who's capable of operating well in high-pressure situations, filtering out irrelevant information, taking in new data while responding to it instantaneously.

Another multitasking test brain experts use involves being given a page of jumbled numbers and letters, and having to ping-pong back and forth between finding them on paper and saying them out loud, matching "A" to "one," then "B" to "two," et cetera.

"You have to keep track of where you are and what you're supposed to be doing," Kramer said. "I mean, it's not rocket science, but when it's part of a multidisciplinary evaluation, those are the things that are really more than a scan, more than a neurological workup, can be sensitive to the early changes associated with a lot of these syndromes."

More straightforward chores patients might be asked to perform in the assessment include drawing something from memory (like a clock), or being shown a picture of a common object, and then naming that item out loud.

Watching the patient in real time, and assessing things like their motor skills, language ability, and eye movements is also key to making a final diagnosis. Often, by the time a family member brings someone in, the news isn't good, Kramer said.

"After our evaluation, we sit down and we say, 'You know, here's some of the skills you need to perform well at your job, and based on our evaluation, you ain't got it, and it's time to hang it up.'"

A full neuro workup requires more than just memory tests

There's also:

Detailed interviews with family members

A review of any other medications the person is taking and preexisting conditions that may make their brain more vulnerable (some drugs can put you at increased risk for dementia.) "A lot of times you just change their medicines a little bit, and they do better," Kramer said.

In general, a focus on ruling out any other non-neurological reason someone might be having some memory issues, like depression, or a deficiency of some kind.

Diagnostics vary, but can include:

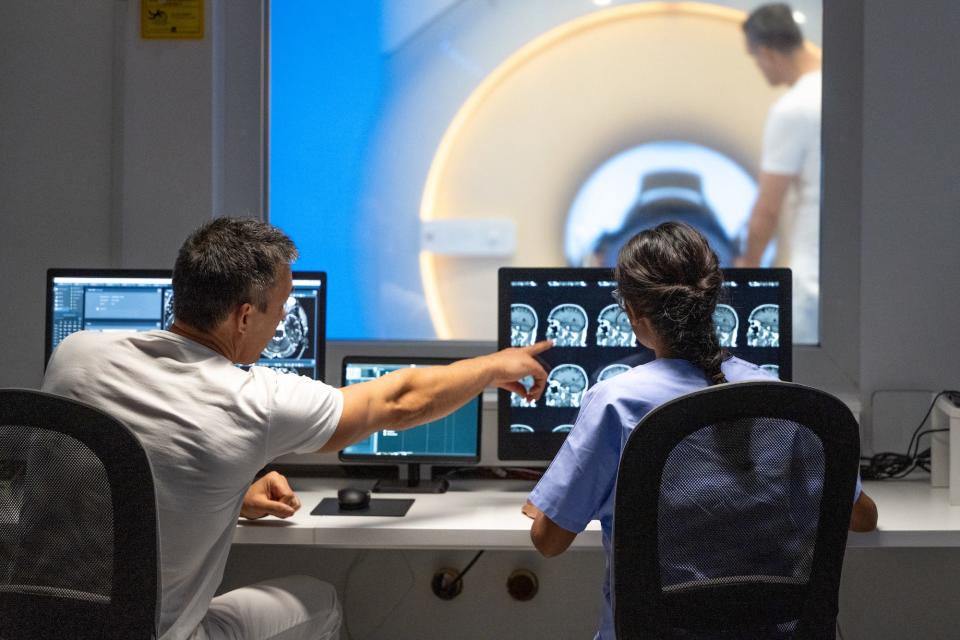

MRI scans to screen for cerebrovascular disease (sometimes caused by tiny, asymptomatic strokes)

A spinal tap or skin biopsy, looking for proteins that may lead to Parkinson's

A new and pricey FDA-approved blood test, scanning for key proteins that put you at risk of developing Alzheimer's

Full blood work, to rule out some other reasons someone might be having some memory issues, like low thyroid or low B12. (Those can be remedied with diet, hormones, or supplements.)

President Biden's latest publicly-available health summary from the White House, released in February of this year, said that Biden recently underwent "an extremely detailed neurologic exam" which was "again reassuring in that there were no findings which would be consistent with any cerebellar or other central neurological disorder." The report also applauded his fine motor skills.

The argument against releasing Biden's cognitive test results

Journalists, including George Stephanopoulos and Dr. Sanjay Gupta, have asked President Biden to undergo new and detailed cognitive testing, and release his results to the public. Given his dismal debate performance, people want to know whether this commander in chief would pass or fail if he took a cognitive exam screening for dementia right now.

"They said I'm good," Biden told Stephanopoulos on Friday. "I have a cognitive test every single day," he added, alluding to the requirements of his job.

Trump continues to boast that he "aced" the basic cognitive tests he took over four years ago, when he was president. But he also has not agreed to a comprehensive public result reveal.

But experts say these tests are not the best way to assess mental fitness for this job. A lot of things are important to job performance that have nothing to do with your memory. These cognitive tests only rule out disease. What would a passing result really tell us? And would a failing result guarantee Biden drops out?

Doctors themselves have resisted mandatory cognitive tests for older physicians — in part because it's ageist, but also because memory tests don't tell you whether someone is good at their job.

"When you're trying to decide who you want to serve in a particular position, i.e. the presidency, what are the characteristics that are really important?" Kramer said. "Is it memory, or is it empathy, or is it problem-solving, or is it a value system that you can relate to, the ability to work with people?"

Read the original article on Business Insider